In Scotland it is often easy to tell whether land is protected for nature, it looks, sounds and feels like nature is doing well.

Ben Dolphin explained this recently in a fine article for walkhighlands (see here) about why Scotland’s Nature National Reserves are a good place to walk. The challenge for both the Scottish Government and the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) is how do you record where nature is doing well or recovering and, conversely, where it is in deep trouble and how do you change that? This post looks at the issues in the light of Scotland’s Programme for Government and the CNPA’s draft National Park Partnership Plan which is open for consultation until 17th December (see here).

Scotland’s targets for nature conservation and what they mean

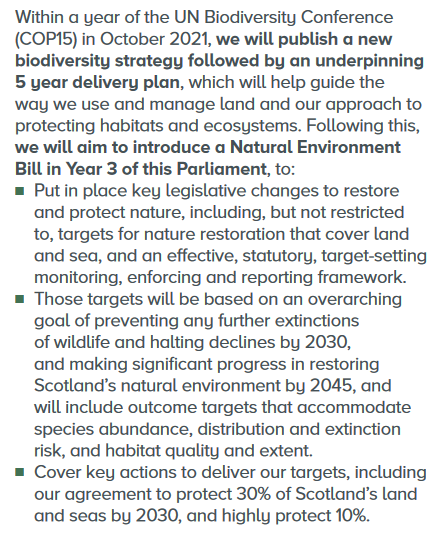

A Fairer Greener Scotland, the Programme for Government 2021-22 (see here), included a commitment that in 2023-4 new legal targets will be introduced to protect the natural environment:

The meaning and difference between “protected” and “highly protected” or how this relates to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s six categories of protected area – a worldwide system for counting whether nature is protected – is not explained. Perhaps this was because how scientists currently work out whether any area of land or sea is “protected” and, if so, to what extent, is extremely complicated. If you doubt that take a look at IUCN’s 2012 handbook on Identifying Protected Areas in the UK (see here).

But Scotland already has 1422 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), the designation that forms the building block of our nature conservation system, “covering around 1,011,000 hectares or 12.6% of Scotland’s land area (above mean low water springs)” (see here). So, does this mean that the Scottish Government believes 10% of Scotland’s land is already highly protected? And, if so, how will anyone be able to judge whether the Scottish Government’s target to “protect” 30% of Scotland’s land and seas has been reached by 2030? As importantly, what are the implications for the climate and nature emergencies of 70% of our land and seas being “unprotected”?

It is instructive to compare the Scottish Government’s targets with those contained in the Nature Recovery Plan (see here) launched by the RSPB, WWF Scotland and the Scottish Wildlife Trust last year. In calling for more Marine Protected Areas they asked the Scottish Government to:

“Commit to a minimum of 30% of Scottish seas being highly protected, of which at least a third is fully

protected”.

They explained that the Marine Protected Area Guide (see here), produced with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, defines “Fully protected” as “no extractive or destructive activities are allowed, and all impacts are minimized” while “Highly protected” is defined as”only light extractive activities are allowed, and other impacts are minimized to the extent possible“.

The Scottish Government’s Programme for Government reads like a watered down version of the RSPB/WWF/SWT’s Nature Recovery Plan. Instead of 10% of Scotland being “fully protected”, it will be “highly protected” and instead of 30% of Scotland being “highly protected” it will be just “protected”. For the technical minded, the Scottish “highly protected” does sound similar to our SSSIs where “light extractive activities are allowed” and damaging operations require consent. If so, that would conform that the Scottish Government believes more than 10% of Scotland’s land is already “highly protected”.

Moreover, the Joint Nature Conservation Committee has counted up all the various designations that apply to landscapes in the UK for a report to the UN’s Biodiversity Conference and claimed as a result that 28% of land in the UK is currently protected (see here). On that definition, Scotland, which has more large designated areas than England, is likely to have met its 30% target for terrestrial habitats already.

Nature targets and the Cairngorms National Park Partnership Plan

According to the IUCN’s classification of Protected Areas, Scotland’s National Parks aren’t real (category ii) National Parks, areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, but (category v) protected landscapes, areas where people and nature interact (see here). The challenge in terms of meeting the Scottish Government’s targets is that clearly much of the Cairngorms National Park’s 4,528 square kilometres isn’t protected. Large areas are being overgrazed and damaged by muirburn through their management as sporting estates.

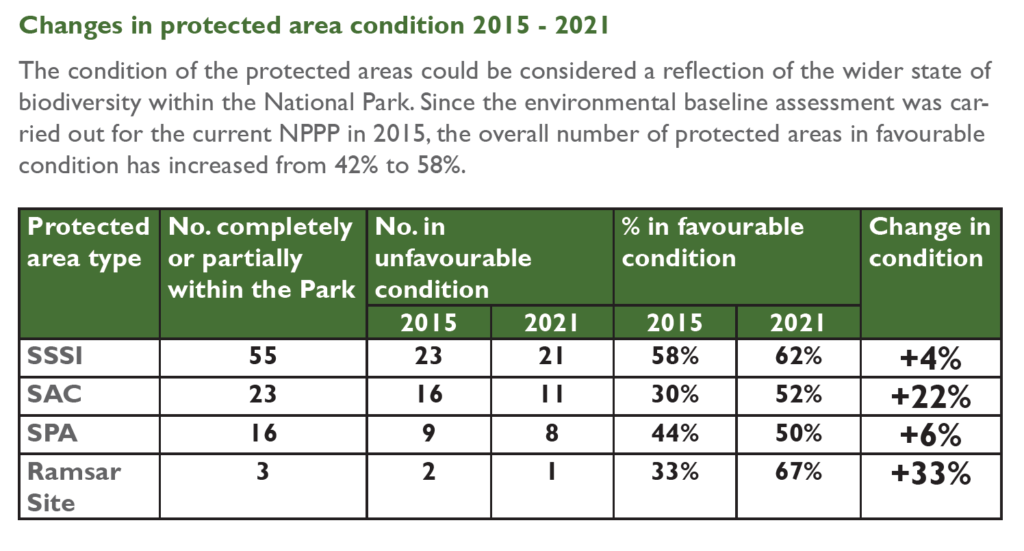

About half of the National Park, however, is “protected” by other designations. Many of these, including most SSSIs, have been classified as the equivalent to the IUCN’s (category iv) “Habitat Species Management Areas”. Unfortunately, these sites aren’t much use either for telling us how much land is “highly protected” or “protected” because a significant proportion are in “unfavourable condition”. The actual situation on the ground is made more complicated because NatureScot reports on condition by site and not by the area of land covered:

“The proportion of natural features in favourable condition on protected sites at 31st March 2021 was 78.3%*. This figure comprises:

- Site Condition Monitoring (SCM) Condition Assessment – Favourable 65.1%

- SCM Condition Assessment – Unfavourable Recovering 6.4%

i.e. monitoring has detected signs of recovery but favourable condition has not been reached. - Unfavourable Recovering Due to Management Change 6.7%

i.e positive management is in place that is expected to improve the condition of the site but this has not yet been assessed on the ground.”

(Extract from NatureScot 2021 site monitoring report (see here))

The figure of 78.3 recovering grossly misrepresents the true position by counting sites that are still in unfavourable condition but are recovering or might do so in future. A very recent study of protected areas across the UK (see here) picked up on this and concluded that because so many sites are in unfavourable condition only 4.9% of land across the UK can really be said to be protected for nature.

This means that the position in the Cairngorms National Park may be far worse than it appears:

Trying to work out the actual position is made more complicated because when the current NPPP was finalised back in 2017 it claimed 81.8% of sites were in favourable position!

If the CNPA has now decided to abandoned NatureScot’s sleight of hand and that explains why the proportion of sites in favourable condition has dropped from 81.8% to c62%, that is welcome. It leaves unexplained, however, how much progress there has actually been in the last five years and why so many sites are in poor condition. Unfortunately, the new CNPA NPPP has followed the example of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority NPPP and is almost devoid of serious analysis. As a result no-one reading the plan would know what the CNPA has actually achieved or much more importantly the barriers to progress and where action need to be taken urgently.

The CNPA’s change in focus from protecting sites to ecological restoration

The draft NPPP has abandoned any attempt to set targets to improve the condition of protected sites:

If Scotland’s designated sites are intended as the best examples of nature in Scotland, why avoid committing to any action to improve the ruinous condition of many of them? How will this help the Scottish Government achieve their targets?

It would be too simple, however, to see this as the CNPA simply abandoning their responsibilities or wanting to avoid being seen to fail. While the state of the natural environment within many protected sites in the National Park is still being seriously damaged through the way the land is being managed and those issues must be addressed, there are also some serious flaws in the current designation system.

The most fundamental is that the designation system was designed to protect particular features and species, rather than nature as a whole. Instead of letting nature evolve and adapt, the current system sanctions muirburn on moorland to prevent it developing into woodland through natural succession. In trying to focus land-management on protecting single features or species, it fossilises the land, failing to consider the much wider benefits that might occur if nature was left to do the job. This accounts for the observation Ben Dolphin made in his article that in most protected areas apart from National Nature Reserves you would have no idea you were anywhere special..

The new emphasis that the CNPA has put on ecological processes in the draft NPPP therefore is to be welcomed:

The change is linked to and supports other policies in the plan, such as that the primary means of expanding woodland should be by natural regeneration and that there is a need to look at the number and impact of gamebird releases in the National Park. It recognises that protected areas are not the only important areas in the National Park for nature and recognises that some “unprotected places” like Glen Tromie are, as a result of the natural regeneration there, soon likely to be far better for nature than many supposedly protected sites. Ecological restoration is a neat way of getting round around the failings of the designation system, as administered by NatureScot, and recognising the good things that are happening on the ground in parts of the National Park.

Nowhere, however, is the change or its implications clearly set out and discussed in the NPPP. Effectively what the change means is that instead of trying to set targets to get specific features in the 50% of the land area in the National Park that is designated into favourable condition, the CNPA will now focus its efforts on trying to get 50% of land in the National Park managed for ecosystem restoration by 2045 (following the examples of Cairngorms Connect and the Mar Lodge Regeneration Zone).

While the change in the direction of travel is generally welcome, there are still a number of serious issues with the shift that the CNPA needs to address:

- The abandonment of targets for “returning” protected sites to favourable condition is letting traditional sporting estates who have been responsible for damaging so many of the sites, off the hook.

- What’s more, while NatureScot has almost never used their statutory powers to force landowners to act on designated sites, at least those powers exist. It is not clear how the CNPA will enforce its target for ecosystem restoration if landowners continue to fail to co-operate as at present. The CNPA makes no mention of what powers would be needed to achieve its new objective.

- The 50% target for ecosystem restoration by 2045 is too low and too slow. It will allow half the Cairngorms National Park, arguably the most important area for nature conservation in Scotland, to continue to be managed intensively for grouse shooting or deer stalking. It will do nothing to fundamentally change how the Royal Family (see here) and other sporting landowners manage their land. A few less deer and avoiding muirburn on deep peat (as set out in other targets in the NPPP) is all that will be required of traditional sporting estates. As for the timescales, it’s as though the crisis in nature didn’t exist.

- Ecosystem restoration requires action at a landscape scale and co-operation between landowners, such as is happening with Cairngorms Connect on the western side of the Cairngorms. Promoting conservation in isolated sites, patches of native woodland behind fences, for example, is not ecosystem restoration. The CNPA will never achieve even its 50% target if it allows specific landowners, whose co-operation is crucial to success, to opt out. The implication is that the CNPA has to introduce zoning to the National Park, showing which places should be primarily managed for ecosystem restoration and then taking action to ensure this happens. If you started doing that you would end up with more than 50% of the land in the National Park required for ecosystem restoration. A good place, however, to start would be with the central Cairngorms massif and the old Cairngorm National Nature Reserve, but that would mean tackling sporting estate management in places like Glenavon (see here) and Invercauld (see here) .

- The CNPA has not said how it will report (to the public and Scottish Ministers) on whether progress with ecosystem restoration is really happening BUT is proposing in the NPPP to develop a Cairngorms Nature Index by 2023. This has the potential to record change/progress. But given the difficulties that have plagued reporting on the state of protected sites, it should be clear some radical thinking is required. It might seem risky, but instead of relying solely on scientific data, why not also ask the public (the dozens of bird watchers, botanists, hillwalkers, anglers etc) who care about nature to report on which bits of the National Park they believe are being restored? That would show that the National Park really is about people and nature.

Behind all these challenges with the CNPA’s proposed change of direction lies the question of the future of the traditional sporting estate. The draft NPPP is silent about that and effectively defers to the Scottish Government on the key questions of muirburn and deer control. That is the NPPP’s greatest weakness and unless that is addressed its good intentions are unlikely ever to be achieved.

In connection with this question of protection designations and active control by statutory authority to monitor and reduce adverse impacts. When we asked SNH (as it then was), to define exactly why our local area was designated SSSI, they looked up the file. There was little in it. I appears that the “blanket” designations locally had been a map based exercise carried out over 30 years ago, in which areas considered in need of protection were circumscribed, and then the file was closed. No one at the then regional office had any data on which to base any monitoring of impacts. There was no photo graphic or soil analysis made, no survey of local ground water or tree numbers. It was just a ring on a map within which some rare species could have been found.

This unhappy conclusion was later supported “in private” by some SNH staff members who were in theory responsible for one of the larger National nature reserves. Because staff changed, due to promotion or re-asignment ,on regular rotation, there was no continuity of oversight: Today’s office teams could have no idea or archival proof to refer to should something gradually change. A species might be in decline, or some development quietly enlarge to encroach into the designated area further. Those granted statutory oversight…those supposed to conserve the SSSI’s with legal powers to enforce, had no visual evidence held on record to refer to. They could not actually act to safeguard anything.

This needs to change. satellite imagery could surely help with this.

I was told that in the seventies at Glenmore capercaillie eggs were taken from nests by forestry workers,chicks reared and fledglings released.I was told that forestry workers were not surprisingly first on the scene at any evidence of fire. My point is that these foresters were part of their community.

Twice in the last three days I have seen crossbills at the edge of spruce plantations.. I.ve watched red squirrels in Kingussie gardens and in pine plantations

I weary and am wary of what seems often a portrayal of “iconic species” of the Cairngorms that`s too simplistic.

I admire what is being done at Feshie but lots of questions? I see extensive felling-will there be planting,? Will Nature take its course?.Is biodiversity or carbon sequestration the priority.Was there not a great deal more biodiversity in the nineteen forties as would seem to be the case reading Richard Perry`s “Inthe High Grampians”.That is when there still was something of the townships.

I agree that so called country sports are the problem. Over grazing,burning,peat damage and the rest need to cease but in the Park`s defence, they are looking to how it is possible to transition-there are jobs to consider-land workers,tradesmen,food outlets..

For me the healing of land needs more and more diverse people on the land.I cycled to a NPPP plan meeting the other week.There were 7 attendees.Locals were either too busy,too unconcerned or else perhaps too content with how things are.It`s not a conspiracy but landowners,comfortably retired,outdoor enthusiasts all have an interest in minimising the poulation. I increasingly believe that people living in this landscape is the real key to sustainability.Is it not selfish to regard the Highlands as an escape?

Perhaps if Nature is left to itself,so long as deer and shooters` activity is controlled-perhaps that is the right way to restore health.

But perhaps repopulation with a broad diversity of humankind would be the best underpinning of Nature`s health

Hi Richard, in response to one of your points, Wildland Ltd has recently consulted on a felling plan for Glen Tromie, which I will cover in a future post, but basically on the fringes of Glen Feshie and Glen Tromie, outside the “wild core” they are in the process of converting former plantations to what is known as Continuous Cover Forestry: instead of clearfell, more limited felling, with natural regeneration and some restocking resulting in a mix of species. Nick

Richard, i agree that the impression is sometimes given,that the ” iconic ” species are reliant on old growth Caledonian pines, when the reality is they can exist in good numbers in more modified landscapes, but it’s about the whole, rather than the parts isn’t it.

With regards to your questions over Wildlands plans for the Feshie / Tromie area, i believe it would be instructive, for interested parties, if an overview, maybe updated annually, could be provided.

I am sure this could be achieved without compromising future planning applications.

With my limited knowledge, with what i have seen,i am more than reassured the right path is being followed.

I have experience, of the early results of continuous cover forestry in other area’s ( although on a smaller scale), and am quite excited by it.

The new plantings in Gleann Chomhraig ( now called, i believe, the killiehuntly woodlands) have recently been awarded “Best new woodland in Scotland”, and will transform the, until now, rather stark but I often thought interesting, valley.

Hi Richard,

For me the healing of land needs more and more diverse people on the land.I cycled to a NPPP plan meeting the other week.There were 7 attendees.Locals were either too busy, too unconcerned or else perhaps too content with how things are.It`s not a conspiracy but landowners,comfortably retired,outdoor enthusiasts all have an interest in minimising the poulation.

I think you’ll find that most Local folk are absoluetly fed up with the national Park and those that run it, the CNP has been the most expensive disaster, millions and millions of pounds spent …. for what.

It’s a very big subject to cover, but this blog provides some important insights to many of the issues and some very good recommendation for improvements on the draft NPPP. On the positive side, CNPA has produced some grains of recognition of the way forward for Nature in the Cairngorms Nation al Park. For me, however, most of the objectives are too vague and open to post-interpretation. Target indicators and linked actions (the latter for some strange reason are shown separately) are either not ambitious enough or only tackle a part of the problem. For example targets for new woodland and peat restoration are far too low. Also there should be a greater emphasis on encouraging (including financial incentives) regeneration over new planting.

As usual CNPA ducks the issue of deer control and intensive grouse moor management. When will this myth be exposed that hunting and shooting is the only way to keep employment in the more remote areas and stop being used as a crutch by CNPA for not tackling the intensive ‘farming’ of our upland areas with the associated losses in biodiversity. This demonstrates the total lack of leadership by CNPA – which should be leading the was forward for nature recovery and biodiversity in Scotland and be seen to be putting real pressure on the Scottish Government to act. How can we pretend to be a National Park and permit the indiscriminate burning of the heather over vast tracts of our upland areas? It’s not just the carbon loading, but the huge loss in biodiversity of these actions, especially the often forgotten small creatures, insects and flora.

I’m not convinced on Richard’s thoughts on re-population. For the first time (I think) CNPA is acknowledging that population in the Park should remain static in numbers. This is a small step forward for CNPA, but I’m not convinced that even maintaining population numbers in the longer term is sustainable – in the Park and countrywide. Going off-piste a bit, I don’t believe there was any real discussion at COP26 on the sustainability of current world population levels – a big omission.