I biked over to the River Dulnain two weeks ago not to search out unlawful access signs on the Dunachton Estate (see here) but to take a look at the forestry and a new native woodland scheme around An Suidhe. There is some lovely woodland surviving on the estate, even if none that I saw was in a good ecological state.

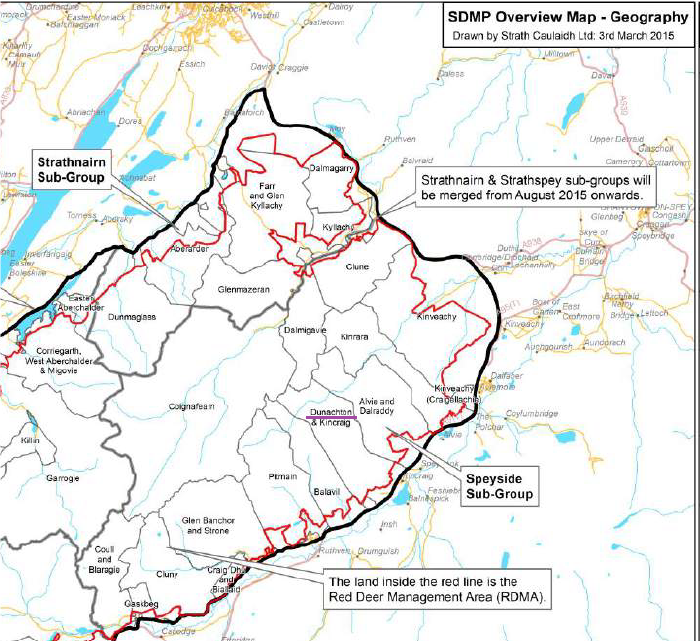

If you didn’t know, you might think it was strange that there were sheep in the birch-juniper woodland on the far side of this fence. But this is part of the Monadliath Deer Management Area boundary and the purpose of the fence has nothing to do with sheep, which were present on both sides, but deer.

The fence encircles most of the Monadhliath and is intended to keep deer numbers in. This has enabled the large private landowners to keep high numbers of red deer for sporting purposes but to keep them away from settlements, including the relatively densely populated area between Newtonmore and Aviemore on Speyside.

Imagine the pressure to reduce deer numbers if they were allowed to descend to the low ground in winter and gobble up local residents’ gardens or cause more car accidents. (Some deer still get through to or survive on the lower ground which is partly why TransportScotland has had to erect deer fencing along the dualled length of the A9 (see here)).

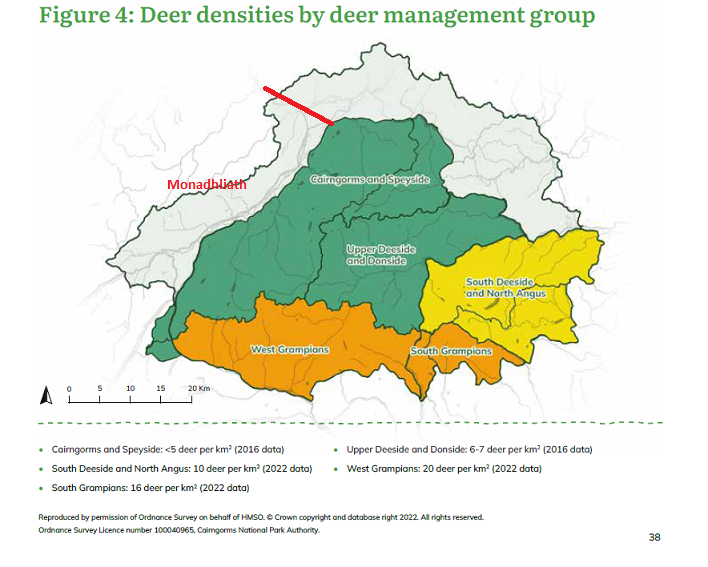

The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) NPPP, approved by the Scottish Minister, Lorna Slater last year, failed to record deer numbers in the Monadhliath. In fact, apart from planning matters, the CNPA appear to have abdicated responsibility for land-use in the Monadhliath part of the National Park to others whether that is BrewDog’s Lost Forest (see here) or “conservation planting” in Glen Banchor (see here).

Cycling up the track I saw two stags. Red Deer head to woodland in winter because of the food and shelter it provides, which is why the Caledonian Pinewood at Kinveachy is regenerating so slowly (see here). The Monadhliath Deer Management Plan 2015-24 refers to proposals from some estates in the group to move the boundary fence downhill to open up more woodland areas for deer in winter. That would be a disaster on Dunachton and most of the other Speyside estates unless deer numbers were radically reduced.

While there was lots of fine old juniper by the track, there was very little sign of it regenerating, despite it being less palatable to herbivores than other trees.

Throughout the juniper and birch there were pheasant feeding stations. Where landowners import the food and there is no need to keep woodland in good ecological health, contrary to the arguments of the game shooting industry which claim what they do is good for the natural environment.

The transition from woodland to moorland was quite sudden, possibly a legacy of former fencing. It appears grazing pressure on this area of moorland reduced for a time, which enabled these new juniper bushes to become established, but they are now heavily browsed. There was no sign of other trees, like birch, regenerating which would happen if grazing levels were low.

As we rode across the moor there were good views of a woodland enclosure on the flanks of An Suidhe. Together with the large patch of muirburn above, it illustrates one of the central contradictions afflicting land-use and conservation in Scotland. Public money is used to pay landowners to grow trees on the one hand, supposedly to lock up carbon and provide a home for nature, while continuing to burn moorland on the other preventing woodland development and releasing carbon into the atmosphere.

From a sporting landowner perspective, however, this is a win win situation: they can shoot pheasants in the native woodland and grouse on the moor above.

With the native woodland enclosure now being extended to enclose the whole of An Suidhe perhaps the muirburn will now stop but it would be better to ban it everywhere.

The track runs more or less parallel to the fence round An Suidhe and passes a large plantation alongside which the deer fencing has been removed entirely, rather than left to litter the landscape. Moreover, it appears the trees have been left to screen the clearfelling behind. Such consideration for the landscape by forestry interests is sadly all too rare.

Sitka, like juniper, is less favoured for browsing which has enabled it to get established, albeit precariously, on the bare mineral soils by the track.

Among the young sitka and protected by them were some deciduous trees, larch, willow, birch. If grazing pressure was reduced further, this whole hillside would in time regenerate naturally.

One risk for the An Suidhe native woodland scheme is that with herbivores excluded, self-seeded sitka will out compete the still-to-be-planted native trees. Instead of spending money on fencing and planting, from a conservation perspective we would be much better reducing red deer, to enable natural regeneration, but then paying landowners to remove non-native trees from areas like this.

Sadly, those working on the new native woodland scheme appears to have been less concerned about removing old fencing but perhaps the contractors or the estate plan to return and re-cycle the redundant wire?

As the tracks skirts round An Suidhe it heads towards an areas of mixed plantation on the Alvie Estate, some of which has been harvested and which looks more natural than most forestry schemes.

At the top of this forestry there were some nice old Scots pine and, while the gate was locked, the wooden fence to the left was still crossable here if you were able-bodied.

Across the fence, what was striking was the number of fences. Four are visible in this photo: one new, three abandoned. I don’t how many were paid for by the forest grants system but the number illustrates the problem. Fences only work for a time, then deteriorate and eventually need to be replaced. The photo represents 50 years or more of failed forestry fencing with more to come!

Fencing matters because it creates crap woodland. Despite the four waves of fencing deciduous trees were conspicuous by their absence within the latest enclosure. Whatever manage to seed here – and there will have been some – none survive because there are too many deer, inside the fence and out.

In the strip along the new fence there were signs of its short-term impact, self-sown seedlings emerging from the heather due to the temporary reduction in grazing pressure. As soon as the deer get back in, however, few if any are likely to survive. Five more years?

New style fencing with chicken wire, designed to keep out not just deer but voles and hares, is even worse than the old style fencing. In bad weather it prevents mountain hare coming down the hill – how many die as a result? – while for humans it poses significant challenges.

While forestry grants now provide for the costs of wooden batons to reduce the carnage among capercaillie and black grouse, it also happens to help reduce the number of red grouse flying into fences. Another grant designed for one thing but which now appears to have been appropriated by some landowners to further their sporting interests. (Alvie is close enough to the surviving capercaillie at Kinveachy to justify this but no fence would be far better).

On our way back, I took another track through the large “commercial” forestry plantation. Behind the screen of trees was a scene of the usual clearfell destruction.

A National Park but no different to anywhere else!

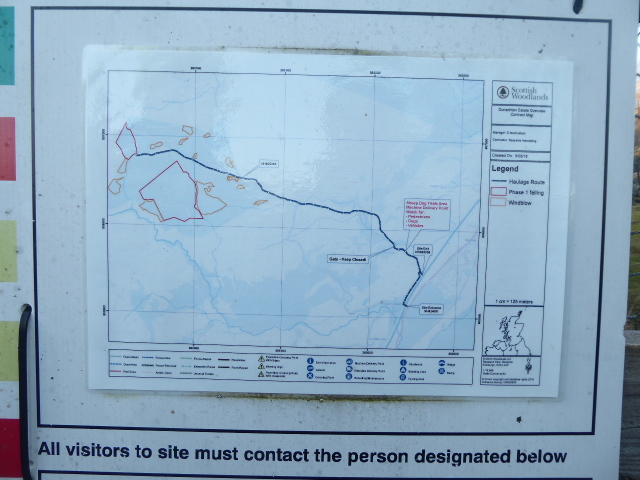

Besides the clearfell, there were large areas of windthrow, which were handily shown in this map from Scottish Woodlands which undertook the felling:

Windthrown timber has no market value and is generally just abandoned. Where the public has paid for the trees to be planted, there is no financial loss to the landowner however. This helps explain why even age plantations with straight edges that catch the wind continue to be standard practice in the forest industry. Landowners, consultants – none pay the price.

There was no sign of any natural regeneration, which might have helped protect the trees from the full force of the wind, around the plantation. Even if continuous cover forestry, which is based on natural regeneration not planting, did not stop windthrow entirely – large storms have flattened areas of Caledonian Pine forest in the past – it would leave far more than the current system. New woodland regenerating around blocks of trees, rather than nothing. The reason we don’t have this in Scotland is quite simple, we have failed to tackle the numbers of red deer because of the power of the sporting landowners. Instead, at great cost, we pay to erect fences which simply don’t work

One good thing about the way this forestry has been managed recently is that Scottish Woodlands have extracted the useable timber without widening the access tracks to the plantation. Proof to the CNPA planners that large new forest roads, such as that proposed for Glen Banchor (see here) and Ralia (see here), are completely unnecessary and should be rejected.

What needs to happen?

What I saw at Dunachton and Alvie is not atypical. Outside a few conservation landowners (and even most of them succumb occassionally) it is the norm. It is how the forestry and native woodland industries work. Public monies, generally, are use to re-imburse landowners for the costs of planting trees behind fences, enabling high levels of grazing by deer and sheep to continue.

The fences usually work just long enough to enable most of the planted trees to get established but no understorey or woodland expansion ever develops because the fencing then breaks down. Or sometimes grazing herbivores are deliberately let into enclosures by sporting interests to provide shelter. The redundant fencing is then rarely removed.

The trees that are big enough to survive browsing by sheep or deer then grow, creating blocks of trees of similar age. In the case of native trees, this creates woodland of limited biodiversity value, while for conifers the trees, unsheltered, either blow over or are clearfelled leaving nothing of lasting value. Just a cash crop or sometimes a failed cash crop, usually subsidised by the public.

There is no evidence that the Cairngorms National Park Authority, since it came into existence 20 years ago, has made any difference to this failed system . That is not all its fault. It now has policies supporting natural regeneration and the reduction of deer numbers, even if it is coy about those numbers in the Monadhliath . But unless the Scottish Government tackle the things that matter, by reforming the forest and woodland grants system to pay for deer culls rather than deer fencing and by banning muirburn, nothing is going to change.

With the SNP leadership election and a new First Minister in prospect there is now an opportunity for our National Parks and for Scotland. Whatever else she might have achieved, Nicola Sturgeon showed very little interest or concern about the natural environment, land reform or access rights. The Scottish Government’s commitments to reform, for example deer stalking or grouse shooting, have been not just weak, they have been delayed and delayed and delayed. Three years after the Working Group on Deer reported nothing has happened. Matters such as the impact of pheasant shooting don’t even appear to be on the Scottish Government’s agenda while in terms of the climate and nature emergency Nicola Sturgeon’s main legacy has been to initiate processes through which much of the ownership and management of the countryside will be handed over to business interests and the financial markets (see here).

Responsibility for this failure lies at the top, with Nicola Sturgeon, particularly given the very centralised nature of government in Scotland. It is time for the SNP leadership candidates and other political parties to dissociate themselves from this record and now use the powers that the Scottish Government has to reform how the land in Scotland is used, putting climate, nature and people first.

I’ve just been reading the forest management plan for a block of commercial forestry near where I live in the Strathnairn part of the Monadliath. Estimated populations are 15/km2 reds, 100/km2 sika plus a transient population (plus they make no mention of the roe). No, that’s not a typo and is over 115 deer per km2.

To be fair the forest managers are embarking on a reduction cull (in preparation for harvest and replanting) but the neighbouring estate that held the shooting until recently should be held accountable. I suspect they saw it as a good reservoir of deer that could get through the porous fence into their land.

The Monadliath deer fence is about 300m behind my house where, for a couple of km, it is a single line of stock fence. Needless to say this doesn’t stop the deer!

It may be above you, however there is a virtually impenetrable full height fence around the top edge of the block forest above Flichity about 500m NW of the summit. My wife, son and I have all independently been caught out in winter being unable to get over or under it whilst needing to descend in snow and impending darkness. It’s astonishing that gated access isn’t mandated every 500-1000 metres simply for the sake of safety?

In recent years the Isle of Luing has been similarly carved up. But that’s OK, on paper we have a right of access!

If there was even a pretence of lip service to access, gates or stiles would be required, forbidden to be locked, and their locations marked on large scale OS mapping.

just as a reminder http://www.parkswatchscotland.co.uk/2016/04/25/monadhliath-natiinal-wildlife-refugium/? fbclid =/w ARDAW9

second attempt http://www.parkswatchscotland.co.uk/2016/04/25/monadhliath-national-wildlife-refugium/? fbclid=/w ARDAW9

Kate Forbes MSP is fully aware of the alternatives as put forward by Derek Pretswell and myself a few years ago

Are commercial grouse and pheasant rearing activities on estates subject to Avian Flu restrictions in the event of an area being designated as infected?

The lack of progress on land reform and reduction in deer numbers has been a huge failing in Nicola’s legacy. Few local MSPs or MPs have stepped up to mark either. Some are quite blatantly on the side of the estates (from all parties).

I have total empathy with that summary, John. It’s a disgraceful position especially for SNP and Green politicians

by way of contrast in this model baxterstatepark.org