On Wednesday NatureScot, formerly known as Scottish Natural Heritage, issued a news release (see here) about how they had entered a partnership with the Hampden & Co, Lombard Odier Investment Managers and Palladium (the company that in in a partnership with National Parks across the UK called “Revere). They described this as:

“a ‘national first’ in ambition and scale, and an important step in positioning Scotland as a world leader in nature restoration through natural capital investment”.

The origins of the initiative lie in a workshop on “Finance for Nature” held at COP26 in Glasgow. It may be a “national first” but this post explains why it is unlikely to work and why it is not in the public interest.

What has been agreed

The news release explains the alleged purpose of the partnership but not how it will work:

“we will use an increasing amount of responsible private investment to pay for new woodland, reducing the burden on public finances and increasing the amount of woodland that can be created”.

An article in the Herald (see here), however, revealed some further information:

“NatureScot said the money [ie the private investment] could be in the forms of loans to private landlords [sic], NGOs and public bodies for projects, but other investment models such as equity investment are also on the table”.

Last year Hampden & Co, a private bank whose customers are the extremely wealthy, produced an informative series of podcasts called “The Return of Woodland” (see here). Episodes 3 and 5 are recommended for those who want to understand more about how green finance works. In them, one of the bankers describes loans for woodland creation as “just the same as any other loan”, i.e the borrower has to pay interest and offer security for the money they have borrowed.

The challenge for anyone who wants to plant woodland is how to meet interest payments until the trees mature. There are various suggestions in the podcasts of how landowners could make money out of new woodland (log cabins, charcoal making etc) but none are likely to produce sufficient income to meet interest payments, while some require even more capital investment. As Hampden & Co put it, this is “not a great sell”.

There is, however, currently a funding gap as Scottish Forestry pay woodland grants in arrears over a period of years. Hampden & Co have seen an opportunity to position themselves as a short term lender, a provider of bridging loans, to enable landowners who are cash poor to pay for the initial costs of tree planting, costs which they later recoup through the forestry grants system. Where state funding is guaranteed, this is a safe loan from a banking perspective but adds no new investment to woodland expansion contrary to what NatureScot is claiming.

Where tree planting is not covered by the forestry grants system, however, loans are extremely risky from both the borrower’s and the lender’s perspective. The Borders Forest Trust, who are named in the news release as being involved in the first pilot scheme, also feature in the podcasts where they explain that the current grants system does not cover the full costs of planting in remote places. That is perfectly true and is one of the reasons why they used volunteers at the Carrifran wildwood. Taking out anything other than a short-term loan to pay for this, however, would be financially disastrous for the charity.

The great green finance hope is that equity investment in the carbon market could be used to pay off these short-term loans. In other words organisations like Borders Forest Trust would borrow money to plant trees, register the scheme for carbon credits and then sell these off to pay back the loans. The problem is that woodland carbon credits for new planting start out as Public Issuance Units (see here) and whether they will increase in value over time, as Hampden and Co explain in their podcasts, will depend not just on how any carbon market develops but also on how the trees fare over time. This is far from a foregone conclusion as a visit to almost any native woodland planting scheme in Scotland will show:

While it is possible for landowners to insure against certain risks, such as fires, other risks such as tree diseases are not insureable. With diseases such as ash dieback and phytophthera ramorum running amok and the increasing incidence of severe storms due to climate change, the woodland carbon market is an extremely risky venture and prices for new PIUs are consequently low. As Hampden and Co point out, selling off PIUs immediately after planting is unlikely to represent good value to landowners. This creates a quandary for anyone considering a loan to plant trees: the likelihood of a good financial outcome is something of a lottery.

NatureScot and the Scottish Government’s justification for using “green” finance

The rationale for this financial partnership was explained by Lorna Slater, the Green MSP and Minister responsible for NatureScot and our National Parks in the news release:

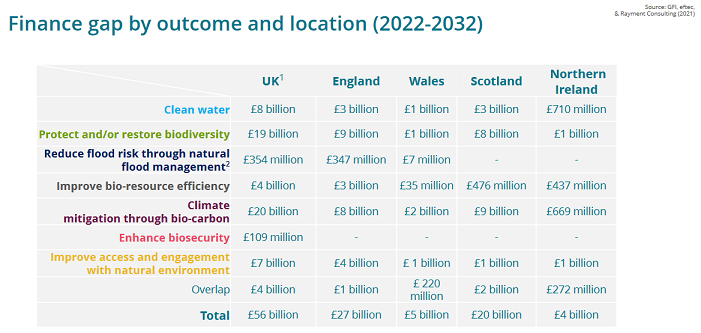

“The finance gap for nature in Scotland for the next decade has been estimated to be £20 billion. Leveraging responsible private investment, through valuable partnerships like this, will be absolutely vital to meeting our climate targets and restoring our natural environment. Scotland is well placed to take a leading role by offering investors the opportunity to generate sustainable returns from the restoration and regeneration of our landscapes. This investment will generate multiple benefits: ending the loss of biodiversity, improving water quality, reducing the risk of flooding, regenerating local communities and creating green jobs” (my emphasis).

Under the FAQs in the news release NatureScot explains how this “finance gap” has arisen:

The Green Finance Initiative, is a private company, set up in 2019 which is partly funded by the City of London. The underlying assumption in the report (see here) , which was produced in association with a range of public officials, is that nothing can change without money. This is very convenient as far as financial interests in the city are concerned but completely ignores nature, both the reasons why it has declined and how it might recover.

The Green Finance Initiative, is a private company, set up in 2019 which is partly funded by the City of London. The underlying assumption in the report (see here) , which was produced in association with a range of public officials, is that nothing can change without money. This is very convenient as far as financial interests in the city are concerned but completely ignores nature, both the reasons why it has declined and how it might recover.

Instead of starting with nature, the report identifies government targets, the potential cost of meeting these, what government funding has been committed to date and from this comes up with funding gap.

This is then glossed by the Green Finance Institute whose CEO Rhian-Mari Thomas is quoted on their website as saying:

“The data is conclusive that public investment – even if funding commitments increase – will not be enough to fund the UK’s nature recovery ambitions. Private investment is therefore urgently required in addition to public sector funding if we hope to transition to a net zero and nature-positive economy.”

One does not have to read very far to realise there are all sorts of issues with the estimates and the data is far from conclusive. For example, the £3b cost of clean water in Scotland was:

“Estimated from EA impact assessment of River Basin Management Plans in England (EA, 2015), where each component of estimated costs was extrapolated to the other devolved administrations”.

So the cost for Scotland is based on data for England where water companies are pouring raw sewerage into rivers because the cost of paying fines has less impact on profits than capital investment.

Far more important, however, than such details – even if they come to a few £billion – is they treat the UK as one big “managed garden”, as one of the Hampden and Co podcast contributors put it, and assume that nothing happens without human intervention. This is completely false.

Nature’s Way

Humans may be influencing how nature evolves as never before, and creating multiple problems for ourselves as a result, but we cannot get rid of natural processes. While we are part of and dependant on nature, it is also distinct from us and has a life of its own. That both threatens us but also offers us salvation. If we could create space for nature, spaces where natural processes were allowed to operate, much of nature would restore itself with very little need for human intervention just as natural processes enabled plants and animals to colonise Scotland at the end of the last ice age. This is what re-wilding should be all about (and not, as sometimes portrayed, removing people from the land).

There are at present three main blockages to re-wilding in Scotland. The first two result from the management of large areas of privately owned land for fieldsports and are the major reasons why we have so little woodland in Scotland and why much of our peatland is in a poor state. Muirburn, the central component of intensive grouse moor management, has destroyed/prevented peat accumulation and the natural regeneration of woodland over large swathes of Scotland. Elsewhere, large numbers of deer have had a similar impact. If the Scottish Government wants to restore woodland therefore, the answer is not to get involved with private finance initiatives but to use its powers to control how land is used and managed.

The answer to the problem of muirburn is simple, ban it. That for tackling red deer numbers is only slightly more complicated. Instead of Scottish Forestry forking out large sums of money for deer fencing, which simply perpetuates the problem, invest that money in stalkers to reduce deer numbers. And where landowners don’t co-operate, get NatureScot to intervene using their compulsory powers under the Deer Act.

The third main blockage to re-wilding, particularly in lowland and more fertile areas, is farming and the way it is practised. The City has not yet worked out how it might make money out of greener farming but, rather than going down that route, the Scottish Government would be far better re-designing the enormous sums of public money that are provided to farmers through the Rural Payments scheme. For example, subsidies could be made dependant on farmers setting aside a proportion of their land for nature. Again, this need not cost much as, if land was set aside permanently it would gradually rewild through natural processes locking up carbon and offering space for more species.

What this shows is that if we allowed “re-wilding” to take place, the funding gap for restoring biodiversity would be far far less than the estimated £8bn. Moreover, since restoring biodiversity is the best way to lock up carbon, the estimated £9bn funding gap for climate mitigation would also reduce significantly.

The implications of the Scottish Government private finance initiative for nature

The speed with which the Scottish Government is acting to facilitate the involvement of private finance in nature contrasts with the glacial slowness with which it is tackling the blocks to enable nature to restore itself through re-wilding.

Scotland’s National Parks are now being viewed as vehicles to enable the involvement of green finance under the guise of tackling the climate and nature emergencies. Refocusing their purpose onto “natural capital” was arguably the core proposal in NatureScot’s consultation on the creation of a new National Park in Scotland last year (see here). Currently, the Scottish Government is looking for new members of the Cairngorms National Park Authority who have “expertise” in green finance (see here). It should be clear now that none of this is a coincidence but part of a concerted attempt to increase the involvement of financiers in the countryside.

On the conservation side, successive governments have talked about reducing the number of deer for thirty years now, during which time they have doubled. It seems that the leadership at NatureScot would prefer to be talking to private financiers than using its powers to reduce deer numbers (see here). It is three years now since the Werritty Review on grouse moor management (see here) and still we are waiting for the Scottish Government to act on its insipid recommendations. As for the rural payments scheme, the Scottish Government has put off any reforms on the basis that it wants to re-join the EU someday. This record is dismal!

But what does this matter if the Scottish Government has been hijacked by financial interests and the real agenda is to use public money (leveraging) to enable “investors to generate sustainable returns”? Contrary to NatureScot’s claims above, it would be far fairer if public money was used in the public interest for public benefit and companies like BrewDog, which claim they are buying up land to mitigate their carbon emissions, were thrown the gauntlet and left to fund any restoration work themselves. That would help differentiate the private greenwashers, starting at the top with King Charles (see here), from the real private conservationists.

While the woodland carbon market may turn out to be a damp squib because of all the financial risks, for those that do get involved it is likely to end in tears, just like the Private Finance Initiative in the NHS. My concern here is less for private landowners than the public and voluntary sector. Some private landowners who are cash poor may use short term loans to access forestry grants but relatively few are likely to participate in high stake gambles with their own assets. For those that do and lose, another wealthy person can always steps in.

The concern should be about the assets owned by the public and voluntary sector and the managerial class who are responsible for the public’s money but bear no personal risks for financial losses like the Chief Executive of NatureNot. In the past the financiers have run rings round these people, hence the £8.5bn bill for £2.9bn of infrastructure projects reported in the Herald a week ago (see here). Public authorities may be short of money but the experience of the Public Finance Initiative and its successors provides even more reason why they should have nothing to do this scheme. One just hopes that the members of the Borders Forest Trust, which has done great work up till now, and other conservation organisations (the other scheme mentioned in the news release is one to restore the Atlantic Rainforest) are not led by NatureNot into the jaws of those who have voracious financial appetites.

Postscript

A few hours after writing this I saw Andy Wightman’s excellent post “Climate Finance and Carbon Offsetting”Climate Finance and Carbon Offsetting also published today following NatureScot announcement. I would hope the two posts are complementary,

This post needs to read by the three candidates seeking to be come First Minister. They need to explain how they they would control over-burning and over-grazing in Scotland and explain how this would restore nature over vast areas, given that the present First Minister had totally failed in this priority task.

Indeed, but I can say that Kate Forbes had a meeting with Derek Pretswell and myself just a few years ago and was given the background to our work with the Loch Garry Tree Group, Scottish Native Woods. New Caledonia and the article I wrote for these posts on the proposal for a national wildlife refugium in the Monadhliath.

20 years ago this year the Duke of Rothesay visited the west Lochaber region. His visit was arranged in support of the Sunart Oak woodlands project ..a local scheme to remove regimented plantations of Sitka spruce and Larch, and then with careful oversight by FLS – but little mechanical intervention- encourage natural regeneration. In the decades since, this far sighted plan has permitted a recovery of the west coast rain forest. Oak, Aspen, Birch,Ash, Rowan, Holly are reclaiming the lost and despoiled hillsides. The blindness ( some might say disinterest) displayed by this Scottish Government to recent history of how taxpayers grant money has been invested in woodland restoration and most other ecological schemes is staggering. Maybe the Minister should instruct her office to re-jig her agenda let her get out a bit more. She could do worse than follow in the Dukes early ‘noughties’ footsteps . She would find an example for herself of how, in the face of the consequences of rampant forestry planting of the 1960’s, rewilding is already being achieved – by unshackling nature itself- at slight cost..

Good points. The new First Minister’s first visit to rural environment after his or her appointment needs to be to Glenfeshie in the Cairngorms where they will learn what Scandinavian landowners can do for Scotland.

Please Dave. Can’t we make the first visit it Creagh Meagaidh, to demonstrate what the government can do. Also it is the first major rewilding project. Remember no trees have been planted there, all natural regen in the absence of domestic herbivores.

perhaps, he, she, it, they, them might learn about who owns Swedish and Danish national parks

Or a visit to Creagh Meagaidh, the original large scale rewilding project, to see what the government can do.

And, of course, back in 2021, Scottish Government officials weighted the selection process for new NatureScot Board members to favour landed interests over candidates with environmental expertise. This policy initiative has been in preparation for some time.

Agriculture in most of scotland is based around intenssive grass management. The worst form being silage. The result of this grass mangement is the loss of meadow flowers, inverts and farmland birds. A prolonged policy of supporting de-intesivication would make make a huge difference in the fight against biodiversity loss.

Is this a better way of funding the environment? I don think so. But is it any better than SEPA earning income by being paid fees to grant licences to damage the environment? A legal framework backed up with policy enforcement is the best way forward.

I guess the simple message is that there is no such thing as a free lunch.

This is an excellent piece highlighting another investment model being contrived (literally) to prop up a system of ownership and management that is utterly broken. As mentioned echoes of PFI and I suspect like bundles of sub prime mortgage investment individuals at either end of the model are unsure of the product they are investing in. Some of the management changes mentioned in the article would have a far less costly and more immediate effect in support of nature, not too mention differing forms of ownership. The trouble is they challenge vested interests and we can’t have that!

The whole thing stinks I’m afraid. Brings back memories of the unholy rush to buy up swathes of Caithness for tree planting by the likes of Terry Wogan, Paul McCartney (or whoever) 50/60 years ago in pursuance of some tax dodge designed for use by greedy punters. Surely Scotland’s wildland problems are bad enough with landowners and politicians calling so many shots, without adding smooth-talking money men into the mix? Nick, thank you, this is one of the best pieces of yours that I’ve read since chancing upon your blog and I only hope it achieves some traction in the corridors of power.

Article and comments all very interesting.

The new First Minister could easily visit Creag Meagaidh, Abernethy, Glen Feshie, Rothiemurchus, Inshriach, and Loch Garry, off the A9, all in one day, and should certainly do so. And then spend another day looking at the work of the Borders Forest Trust, and another day at least seeing west-coast rainforest – and then join the Native Woodland Discussion Group for regular, timely top-up experiences thereafter. It might be life – and environmental politics – changing…

Finally got round to reading this – excellent blog.