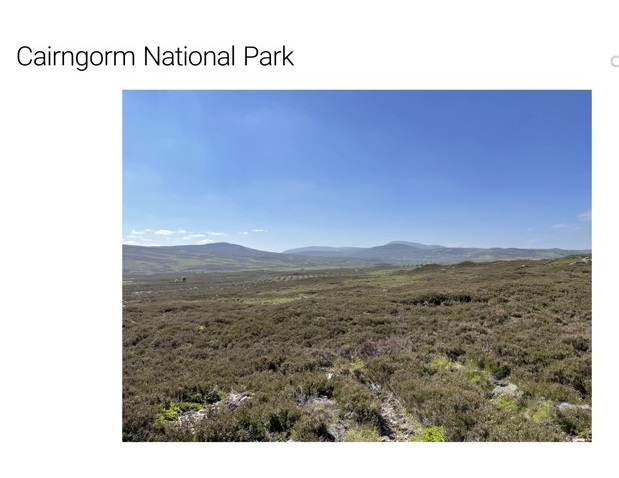

In September it was widely reported (see here for example) that Standard Life Investments Property Income Trust (SLIPIT) had purchased 1,447 hectares of land in the Cairngorms National Park for £7.5m as part of its carbon strategy. This followed BrewDog’s purchase of Kinrara earlier in the year for similar purposes (see here) . This post is the first in a series that will take a critical look at the increasing interest of businesses in buying up land in our National Parks and its likely consequences.

What is SLIPIT?

SLIPIT’s purpose is, as it names suggests, to provide income to shareholders from investments in property and at present it does this through three main commercial property sectors: office, retail and industrial. The value of its property portfolio is c£450m. SLIPIT is managed by Standard Life Investments and is part of ABRDN, the asset management company formed by the merger of Standard Life and Aberdeen Asset Management in 2017 and one of the biggest such companies in the world. SLIPIT trades in the UK as a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) and is exempt from corporation tax but is registered in Guernsey, well known for its low taxes and lack of transparency on tax matters (see here).

SLIPIT’s purchase

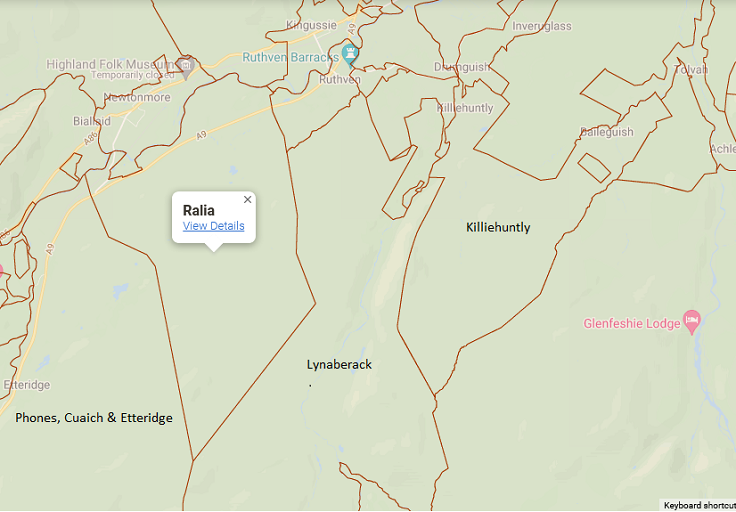

SLIPIT did not reveal the whereabouts of the land when announcing the purchase, although you might have been able to work it our if you had viewed the accompanying fund update video (see here – under “latest news”) . But a few weeks later a consultation meeting in Newtonmore confirmed SLIPIT had bought part of the Ralia Estate on the far side of the Spey from village.

The area SLIPIT has purchased is on the eastern side of the Ralia estate, part of which borders the Glen Tromie watershed and the Lynaberack estate which is owned by Wildland Ltd. SLIPIT’s announcement stated that the land it had acquired is no longer much used for grouse shooting or deer stalking and had little “sporting” value. It appears, therefore to exclude the part of Ralia that borders the A9 and is heavily used for pheasant and partridge shooting.

The price in perspective

SLIPIT paid £7.5m for 1447 hectares (3575 acres), equivalent to £5183 a hectare or £2097 an acre.

By comparison, the Guardian reported that the local community at Langholm had bought “just over 2,000 hectares (about 5,000 acres) of Langholm Moor for £3.8m” last November (see here). That comes to £1900 a hectare or around £760 an acre, considerably less than half the price by SLIPIT. The Findlay family who own Ralia must have been rubbing their hands even more the Duke of Buccleuch at Langholm, where campaigners like Andy Wightman and Lesley Riddoch (see here) were highly critical of the asking price.

In the summer it was reported (see here) that hill ground had recently been valued at between £600-800 an acre but was going for twice the price because of demand for “natural capital”. The price SLIPIT paid, exemplifies that process but has taken it a step further.

SLIPIT has been able to pump up the price of hill land because there are no controls over land ownership in Scotland, not even in our National Parks.

SLIPIT’s intentions in buying Ralia

Despite being registered in Guernsey, SLIPIT claims it takes Environment, Social and (Corporate) Governance (ESG) Governance ((see here) for explanation) very seriously. It issued this statement to shareholders in June when it hinted it was about to make a major purchase:

“ESG factors are integral to the Company’s decision making and strategy. We are engaging with tenants on installing more PV units on roofs, installing EV charge points, and upgrading units where

required to support strong ESG credentials. We recently contacted every tenant to understand their energy consumption, waste policies, etc. It is still disappointing how many refuse to share such data but more have than in previous years and that is helping us build a more accurate understanding of the carbon footprint of the Company, so that we can move to a net zero route path. As part of that, the Company is exploring ways to offset residual carbon from operating its portfolio in such a way that guarantees not only a gold standard of offset, but also gives a fixed price solution. This will mainly comprise reforestation and peatland restoration, and the Company looks forward to sharing more details as soon as it can. It is very clear to us that ESG will be a major driver of performance in the future.”

At COP 26 the UK Government announced that from 2023 UK companies will have to produce detailed plans to show how they will meet climate change targets (see here). It appears that SLIPIT foresaw the direction of travel of the UK Government and decided to get in there first.

While SLIPIT has started to invest in measures that will help to reduce its use of fossil fuels (solar panels etc), bringing its industrial and retail properties up to “passivhaus” standards or heating them through renewable energy would almost certainly be very expensive. Hence the reference to carbon offsetting as “a fixed price solution”. In the video SLIPIT refers to divesting itself of a couple of properties that did not meet ESG requirements, i.e they have off-loaded the problem of what to do with buildings that are likely to be too expensive to fix onto someone else.

This approach is completely unsustainable and will compound not solve the problem of carbon emissions. If wealthy REITs, which are exempt from corporation tax and in SLIPIT’s case are sitting on bags of cash, are not prepared to invest in making their properties carbon neutral, what hope for anyone else? The simple fact is there is not enough land in Scotland or indeed the world for richer people and organisations to decide to offset their emissions rather than tackle them.

The SLIPIT fund managers are no fools and have realised that land prices are likely to increase significantly as demand for carbon offsetting increases: “We believe that being an early mover will give the Company an important advantage in future costs for offsetting as society moves to net zero by 2050“. And if at some time SLIPIT decided to deal with its emissions rather than offset them, it would have an extremely valuable asset it could dispose of to pay for such work.

What does SLIPIT intend to do with the land at Ralia?

With assistance from Kilrie Trees, “a natural capital developer” (see here), SLIPIT worked out a plan for the land prior to agreeing the purchase:

“The site supports 956 hectares for planting with natural broadleaf trees (about 1.5m trees in total) with approximately 115 hectares for peatland restoration, with the remainder open land to support bio diverse habitats. The site is expected to sequester approximately 195,630 tonnes of carbon up until 2060, representing 73% of the Company’s residual embedded and operational carbon”

While SLIPIT in the video has stated it doesn’t expect to derive any income from the land, the signs are it doesn’t expect it to cost anything either. The news release states: “It is anticipated that the costs of planting will be met through grant funding.” Moreover the peatland restoration is likely to be paid for out of the £250m fund the Scottish Government has set up for this purpose. The initial plan from Kilrie/SLIPIT appears to be to fence the trees, which would save having to employ a stalker.

One cannot fault SLIPIT’s carbon strategy from a financial perspective. Buy up some land, let the Government pay to restore it so it starts absorbing more carbon then just sit and wait until you can reap the financial benefits.

The implications of the purchase

It should be obvious that SLIPIT’s purchase of Ralia is likely to have serious consequences for the Cairngorms National Park and Scotland more generally.

- The astronomical price paid for the land is more than a major set back to aspirations of more community land-ownership in Scotland, it promises to price local communities out of the market and the end of that dream.

- The purchase appears to offer nothing to the local community, potentially not a single job if the fencing proposal is allowed to go ahead. By contrast, Wildland Ltd may be owned by billionaire Anders Povslen and to have been subject to some criticism locally, but it is a different model of “rewilding” which employs significant numbers of local people.

- This purchase and that of Kinrara marks the introduction of a new breed of landowner, one who knows nothing about the Scottish uplands, nothing about the natural and human history, nothing about ecology and nothing about the people who live in the area. Moreover, this breed of landowner is likely to have even less connection to the land in future than the absentee sporting estate owner who turns up a few days a year for some shooting.

- Instead, these landowners – whose only real interest is in the financial value of carbon – are likely to employ one of the dozens of businesses which are springing up, presenting themselves as experts of natural capital. A new breed of factor, the natural capital consultant, may be coming to the Highlands.

What needs to happen

While no-one can undo this purchase, SLIPIT could think again about what it is actually going to invest in the land at Ralia and how it might manage it. A first step might be for SLIPIT to assume responsibility for meeting ALL the costs of “restoration” work and forego any public subsidies. A second would be to re-think the proposal to plant trees and protect this by deer fencing.

Part of the land purchased adjoins to Glen Tromie where, as a result of a reduction of deer numbers to less than two per kilometre, trees are regenerating everywhere with only very limited planting and without deer fencing. Just as BrewDog needs to ensure what it is doing at Kinrara fits with natural regeneration of the Caledonian Pinewood at Kinveachy, so SLIPIT needs to ensure what it does re-inforces the approach to re-wilding that is taken by Wildland Ltd at Glen Tromie. That should mean employing stalkers – they could probably contract Wildland Ltd to do this for them – and NO fencing.

Whether or not SLIPIT follows this line, both Scottish Forestry and the Cairngorms National Park Authority should revisit the criteria they use to award forestry and peatland restoration grants as a matter of urgency. Both need to stop subsidising people and organisations who are buying land to speculate on “natural capital”.

As a start, Scottish Forestry could stop paying out money to landowners items like deer fencing and plastic tree shelters and instead insist that private landowners bring down deer numbers to the level necessary for natural regeneration to work. It should then take account of issues like whether landowners are paying their fair share of taxes to decide whether they received grants to assist with deer control.

The CNPA is now responsible for the administration of grants for peatland restoration within the National Park. While continuing to play an active role in the design and monitoring of peatland restoration schemes, the CNPA could insist that owners like BrewDog and SLIPIT meet 100% of the actual costs of doing the work instead of paying for most of this as at present. But for that to happen they need to amend their draft National Park Partnership Plan:

Purchase of land rather than provision of finances to support rewilding, as appears to be happening at Ralia, should NOT be counted as “green investment” and the new NPPP needs to make that explicit. Rather, such purchases should be treated for what what they are, a form of land speculation by businesses as a means of avoiding having to cut their own carbon emissions which should have no place in our National Parks.

The CNPA doesn’t have the power at present to prevent that but it should be making clear that speculative land purchases, like SLIPIT’s £7.3m acquisition of Ralia, will not count towards its £250m target for private investment in nature. It should also be asking the Green Minister for National Parks, Lorna Slater, for new powers to vet all new landowners prior to any purchase going ahead. This should be to ensure that what new landowners intend to do is compatible with the National Park’s statutory objectives and will bring real new investment to the area.

Brilliant investigation Nick – you have highlighted so much here that needs to be flagged – and there more. I am sure these guys will be looking to make money by ‘selling’ Carbon Credits even though they state that this project is to make up for their own failures elsewhere. Its all bunkum. But there’s lots more. Have you looked at foresight sustainable forestry – They have just launched with £130m much of which will be used to buy up Scottish land for afforestation – and of course Gresham house. And who are Kilrie Trees – established just a year ago, Who are they and what experience do they have…?

Well done, Nick, for presenting a powerful argument – views I have shared even since the Brewdog purchase. At the heart of the problem is Scottish Government policy and also to be fair UK Government policy. If the system is set to encourage carbon offsetting as a replacement for other measures to reduce carbon footprint – this is the result. Additionally lax rules around, funding for tree planting and peat restoration reinforce the problem. Grants for such work need to have clear and demanding criteria, including assessing whether a land owner has continued to cause environmental damage by constructing vehicle hill tracks. Is it the case that the funding around tree planting encourages physical tree planting rather than natural regeneration? Unless our governments stop behaving so naively and manage these grants to best advantage, this will always be the result.

Lastly, I ‘m not letting CNPA off the hook. Too many times CNPA is seen to be just promulgating inept government policies, instead of showing the leadership we should expect from a National Park in showing the Scottish Government what it should be doing. CNPA should be seen as a strong advocate for the introduction of progressive environmental policies which will repair the swathes of the National Park damaged land and promote real biodiversity and carbon sequestration – and thus become an example for many other areas of Scotland.

The latest consultation on the Partnership Plan is another clear example of too many ‘motherhood and apple pie’ objectives and no real plans or targets to achieve. Unless radical changes are made to the draft plan the new 5 year plan will be consigned to the long list of CNPA failures – just like the Partnership Plan it will replace.

Hi Nick

V interesting. At the end, it says there have been 7 comments, but I can see only 2??

Five are pingbacks from other posts, trying to work out why they are not shown, Nick