How many of the trees planted at Kinrara last year have survived?

How many of the trees planted at Kinrara last year have survived?

After my posts in the autumn about the destruction being caused by BrewDog’s tree planting at Kinrara and how it has been releasing carbon into the atmosphere (see here) and (here), I heard through a third party that someone with professional expertise thought that 90% of the trees planted last year with Scottish Forestry funding had died. I knew it was bad, based on the relatively small areas I had seen, but not that bad so I decided to check further.

First I submitted a Freedom of Information Request to Scottish Forestry for all the correspondence they had had with BrewDog about the work that had taken place on the Lost Forest in 2023, any information they held about how many of the planted trees had died and how much of the forestry grant due in the year 2023-24 had been paid and whether any of it would be reclaimed. For various reasons, including emails that seem to disappear into the ether, I am still waiting for a response. What hard facts there are should become public in due course.

Second, I visited Kinrara again on 30th December to have another look. While the light snow made it easy to see where most of the trees had been planted, determining whether the stems of recently planted deciduous trees are alive in winter is not so easy. From the areas I walked over the survival rate of deciduous trees appeared highly variable but overall I thought it was higher than 10% with places (as above) where there were quite a few stems still standing.

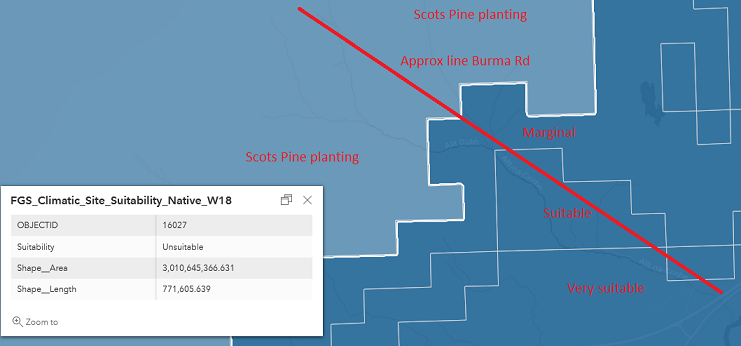

The Scots pine planted along the western boundary of the Lost Forest, which we walked down after visiting the summit of Geal Charn Mor, were another matter.

High up, there were dead planted pine everywhere and I couldn’t find a single live sapling although there were a couple of naturally regenerated saplings in the undisturbed parts of the heather. I was beginning to wonder if none of the Scots pine had survived until, near the bottom of the hillside, a number of live saplings appeared. If the route we took was in any way representative, it did look to me like at least 90% of the planted Scots Pine may well have died.

If so, that will raise yet more questions about the governance around Scottish Forestry’s grants system and whether it in the public interest. On the governance side there are questions about why Scottish Forestry ever agreed to fund planting of Scots pine in areas which they own mapping had shown was unsuitable for planting:

What is BrewDog actually investing at Kinrara?

The unaudited financial statements for the Lost Forest for the year until December 2022 appeared two months late on 30th November 2023 (see here).

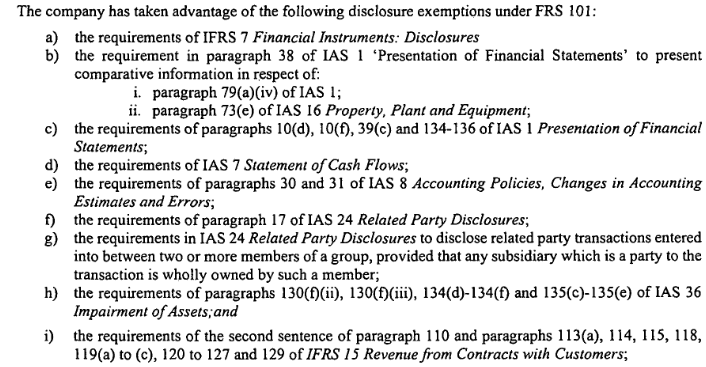

BrewDog doesn’t appear to have applied “radical transparency” to its subsidiary that owns Kinrara but instead has taken advantage of extensive reporting exemptions which are available for small companies under the Financial Reporting Standards:

Perhaps, rather than relying on businesses to be open about what they are doing, it should be a condition of all grants issued by Scottish Forestry that the companies who receive them DON’T take advantage of the exemptions under FRS101? As finance drives most things, including carbon emissions, this would enable the public and the public authority staff who are responsible for monitoring contracts to see what is really going on.

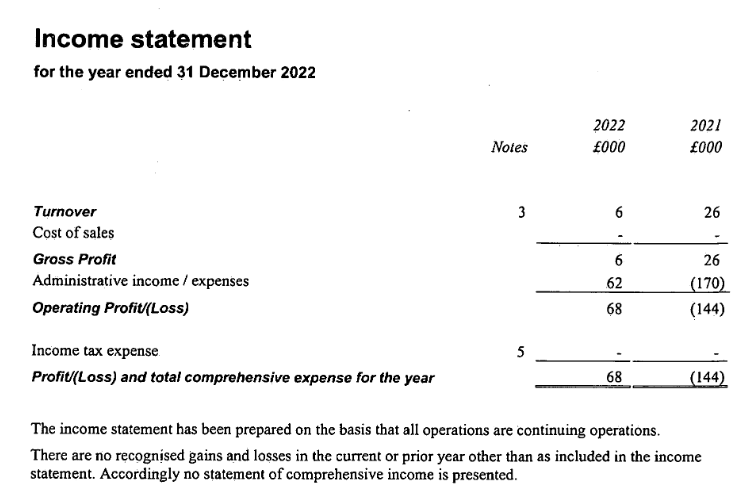

The consequence of these FRS 101 exemptions is the accounts for BrewDog’s Lost Forest don’t reveal a great deal:

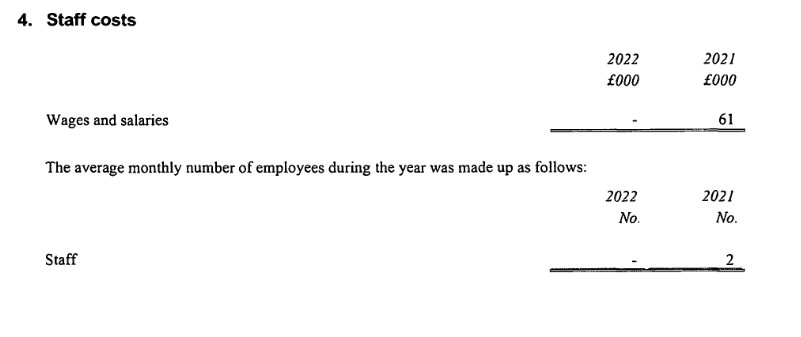

The income statements shows that turnover reduced to a mere £6k, the company £68k profit compared to a £144k loss for the previous year and paid no tax on that profit. The reduction in administrative expenses suggests very little money is being spent operating the company and is partly explained by staff costs reducing from £61k to nil.

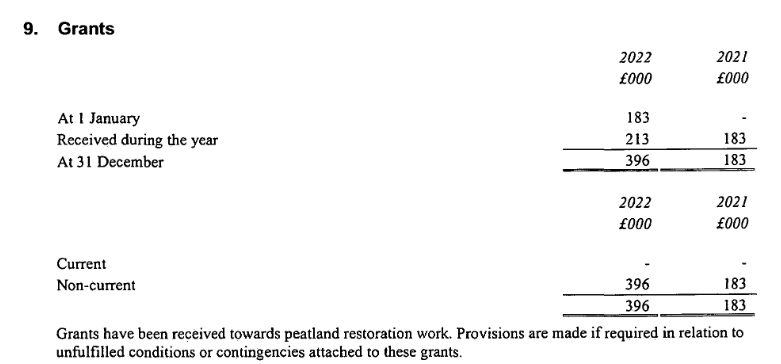

The notes to the accounts also show that the Lost Forest received £213k in 2022 government grants for peatland restoration (and that none of the grant funding approved by Scottish Forestry was paid in that year):

The grants have been treated as non-current liabilities because until all the conditions are fulfilled the money could be paid back. They thus appear neither in the income column or under assets as an investment in the land.

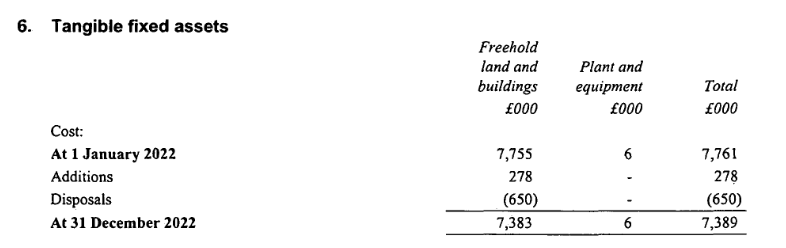

The disposals line under Tangible Fixed Assets shows BrewDog sold some £650k of the company’s assets, most probably buildings. It appears, however, that instead of being re-invested in the company the receipts may have been used to pay BrewDog back the money it paid for Kinrara. That “investment” by BrewDog has been treated as a loan to its subsidiary, the Lost Forest, and appears in the company balance sheet as as debt.

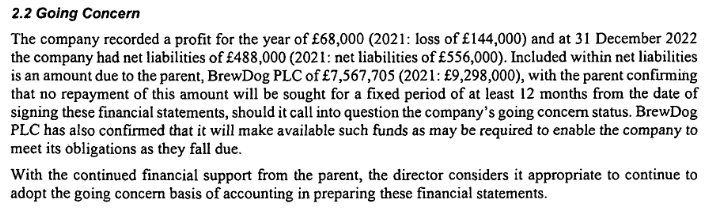

Both the balance sheet and the statement of going concern suggests the Lost Forest paid back almost £1,800,000 to BrewDog in 2022. Around £1,200,000 of this appears to have come from cash held by the company and only place the rest of this money could have come from was “disposals”

The financial statements are so limited that its not possible to understand properly what is going on but for 2022 it appears that the Lost Forest invested very little money in the land it owns at Kinrara while BrewDog took a significant quantity of cash out of the company.

Mortgaging the land and for what purpose?

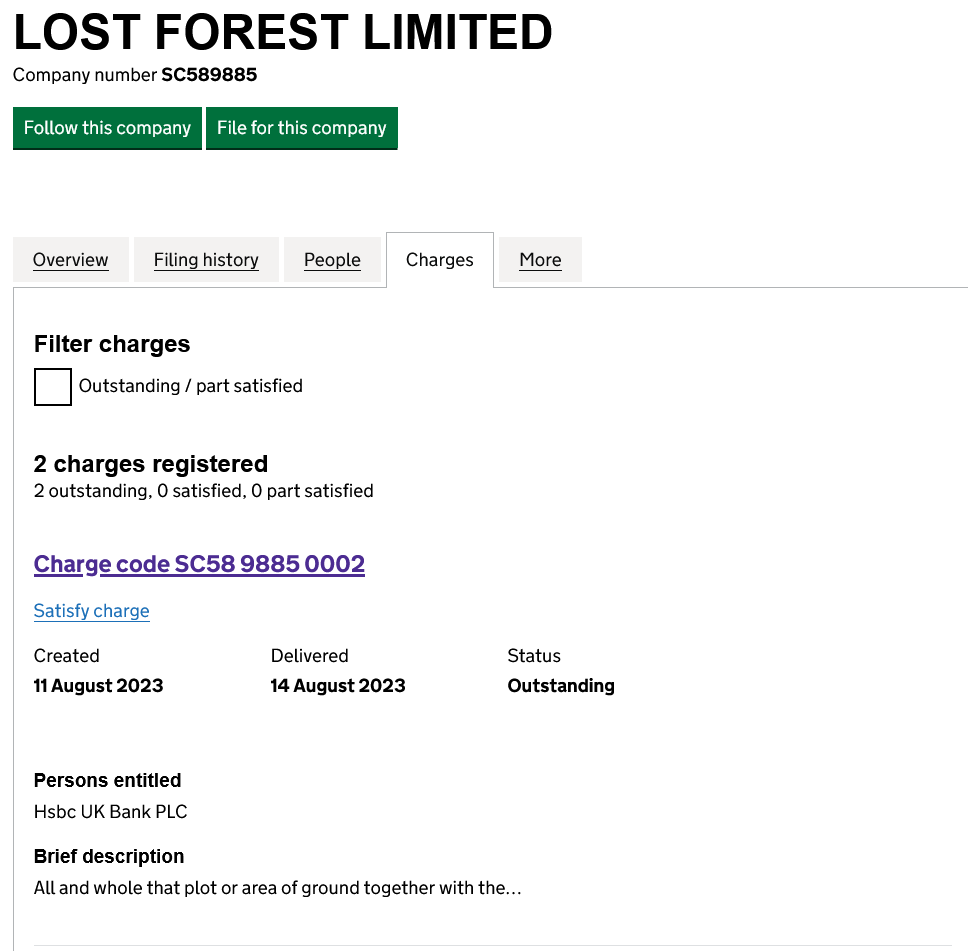

In 2023, i.e the year following these financial statements, HSBC lodged two charges against the land at Kinrara for loans taken out by the Lost Forest, one in May and a second in August. These are shown on the Companies House website as follows:

The charges lodged at companies house do not contain information about the value of the HSBC loans to the Lost Forest or the interest rate although they do show that they have been secured against the entire property.

The purpose of these two loans in unknown. If Scottish Forestry enforce the conditions of their grant, which requires a certain density of tree cover to be achieved, the Lost Forest will almost certainly either need to repay it or pay for a lot more tree planting out of its own funds. It seems unlikely, however, that the loans were taken out to plant more trees as by August BrewDog would not have been fully aware of the extent of its planting disaster or the consequent financial liabilities it faced.

It seems more likely the loan was used for another purpose, perhaps to pay back more of the outstanding loan shown on the books as owing to BrewDog by taking out another loan on which it must now be paying interest.

Accounting for the Lost Forest – BrewDog needs to account for what’s gone wrong

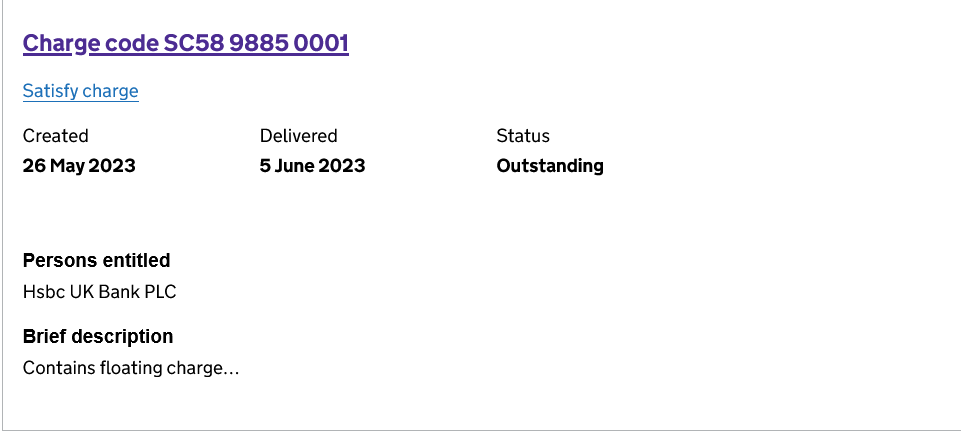

While BrewDog appears to be making more effort to account for and reduce its carbon emissions than many other companies, it never appears to have properly explained how the Lost Forest fits into this and whether the purchase was part of a plan to offset residual emissions it cannot avoid. Neither BrewDog PLC’s accounts for 2022, published in summer of 2023 (see here), nor its Mega Sustainability report v.5 for 2023 (see here) explain the Lost Forest’s place on its carbon balance sheet.

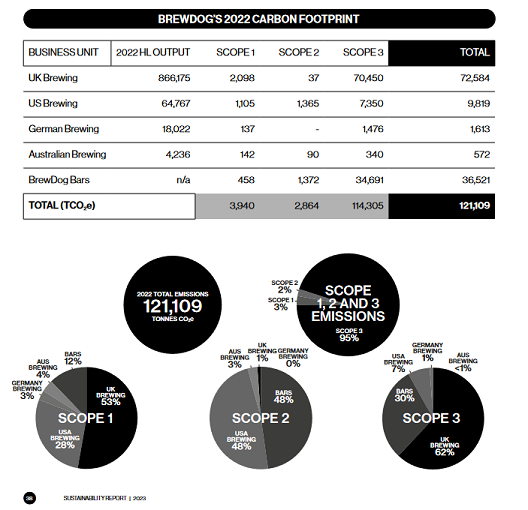

What does “reclaiming the stunning Scottish landscape for future generations” actually mean? BrewDog’s deer fences are likely to have been stunning a lot of birds and causing ecocide for the capercaillie (see here) while the landscape itself has been wrecked. BrewDog and its advisers, however, appear to carrying on as if nothing has gone wrong with the nature restoration aspects of the project:

While Prof Mike Berners-Lee is right to say there is “really no such thing” as a carbon offset, from a carbon emissions perspective the Lost Forest has been registered under the Woodland Carbon Code and the paperwork for that shows it will be emitting carbon for the next 15 years. With so many trees having died and so much peaty soil disturbed, it will now be longer than that. It has become a carbon liability that is now hanging round BrewDog and the Cairngorm National Park’s neck. That needs to be officially recorded by BrewDog in its next Mega report.

Meantime, the accounts for the Lost Forest for 2022 reinforce the argument I made a year ago that BrewDog does not itself appear to be investing money in the Lost Forest and the Guardian was right to challenge its claim for its Lost Lager that “for every pack we plant a tree in the BrewDog Lost Forest” (see here). Those adverts are long gone but BrewDog was still calling its Lost Lager “planet first lager” in its 2022 annual report and is still giving the impression to its “equity punk community” that the company is investing in the natural environment:

The truth is that almost all of BrewDog’s Lost Forest appears to have been funded to date by Scottish Forestry, i.e the public rather than any punk investors.

The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) should now be very concerned about how BrewDog’s financial position affects what happens next. BrewDog as a company made an increased loss in 2022, which may help explain why it took cash out of the Lost Forest, but its subsidiary would appear to have no source of income aside from government grants. If BrewDog’s grand plan was to raise money in future by selling carbon credits through the woodland and peatland code, a large part of that plan would now appear to be in tatters. Why would anyone buy “issuance units”, as they are called, for the Lost Forest Phase I when it will be leaking carbon into the atmosphere for another 15 years?

All of this reinforces the argument that before anyone is allowed to buy large areas of land in our National Parks they should be required to show how they will manage the land in a way that meets statutory objectives (including sustaining local communities) and how they would finance this. Had BrewDog been required to undergo such tests they might never have bought Kinrara.

Meanwhile on the Kinrara estate an application has just gone in for a telecoms mast, 2 small wind turbines and a solar panel array at about 500m. SRN strikes again.

Do you have a link for this information please

Perhaps modest when considered against two current proposals in scoping for over 50 x 200m tall wind turbines plus access, storage batteries and above ground cables to sub station on two sites on estates adjacent to the north and west of Kinrara. If approved, the landscape in the upper Dulnain will look very different.

Hey Nick, you caption your last image with the following statement

“ Extract from 2023 Mega Report – BrewDog appear to say a large proportion of those saplings are now dead”.

I’m not seeing anything where Brewdog say this.

Please can you reference the source ?

Thanks.