On Thursday the Wildlife Management and Muirburn Bill (WMMB) (see here for text) was passed by the Scottish Parliament. Judging from the responses of some of the main proponents and opponents of the Bill one could be fooled into thinking will usher in major changes to how grouse moors are managed. On the one hand the RSPB described it (see here) as “a huge win for nature” and Chris Packham as a “gamechanger” (see here). On the other Scottish Land and Estates (see here) described it as a “seismic change” and the British Association of Shooting and Conservation claimed (see here) it would have a “ruinous impact” on the rural economy and “damage the countryside”.

The response from Revive, the coalition for grouse moor reform, was more measured (see here):

“This Bill ……………finally regulates a controversial industry that’s responsible for environmental destruction, that restricts economic opportunities for rural communities and that kills hundreds of thousands of animals so a few more grouse can be shot for sport.

“While it doesn’t go far enough to end the ‘killing to kill’ on grouse moors, banning snares – the cruel and indiscriminate traps that are common on grouse moors – is an important win for animal welfare against an industry that was desperate to keep them.

“The extra protection of peatlands is welcome but with three quarters of Scots against moorland burning for grouse shooting, the Parliament still has some catching up to do.“

This post will argue the WMMB should be viewed as a conservative and limited piece of legislation, which could potentially make it harder for Scotland to achieve its climate change and nature restoration targets, but nevertheless offers some opportunities for further reform.

Background to the legislation

The origins of the bill lay in the unlawful killing of raptors on grouse moors, although most of those concerned about this persecution recognised this was simply a part of wider land-management practices designed to produce the maximum number of red grouse possible.

Despite the Scottish Government issuing repeated statements that raptor persecution was unacceptable (see here for timeline from Raptor Persecution Scotland), it took years before they set up the Werritty Review into grouse moor management. Instead of taking a holistic view, the Werritty Review Group excluded key grouse moor management practices, such as the construction of hill roads and the drainage of peatland, from consideration.

It took the Scottish Government a further year to respond to Werritty’s limited proposals and then another consultation before it came up with proposals to license: trapping (including a ban on glue traps); grouse shooting and muirburn (see here). Meantime, the Green MSP Alison Johnstone managed catch the Scottish Government off-guard (see here)and increase legal protection for mountain hares – which had also been relentlessly persecuted on grouse moors – through a last minute amendment to the Animals and Wildlife (Penalties, Protections and Powers) (Scotland) Act 2020.

The Scottish Government’s acceptance of the need for Grouse Moor Reform has always been strictly limited – it has yet to recognise the link between muirburn and flooding (see here) – and this was reflected in the comments from the new Minister, Jim Fairlie, during the Stage 3 debate last Thursday:

“There were those who disagreed with the principles of the bill, but if the grouse-shooting community had shut down raptor persecution—stopped the killing of our most iconic birds of prey—we would not have had to legislate in this way. Sadly, that community did not shut it down, so it is now up to us to make sure that it does so. It is for that reason that the bill is before us today.”

This apparent lack of awareness of the other impacts of grouse moor management or how these might impact on other Scottish Government policy objectives is striking. So what are the main flaws in the bill?

Trapping of wildlife

The most significant changes introduced by the WMMB concern animal welfare. OneKind and the Scottish League Against Cruel Sports managed to persuade the Scottish Government to add snares to their proposals, which initially only included a ban glue traps, and the bill tightens up oversight of traps through a new licensing system.

The land management organisations have issued extravagant claims about the impact this will have. For example, the Scottish Gamekeepers Association (see here):

“We have deep fears for the future of red-listed species [i.e birds whose populations are on the edge] because of the snaring ban. The impacts of this step must be robustly reviewed and challenged, if need be.”

Snares are used to catch foxes and rabbits. Recent research from the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust (see here) shows the SGA’s claim is nonsense: “We had data from 74 gamekeepers, all of whom favoured lamping as their principal means of fox control”. Whatever you think about the need for predator control, snaring no longer plays a very important role.

The truth is that while the means by which gamekeepers can now lawfully control mammalian predators such as foxes, stoats and weasels will now be more strictly controlled than previously, there are still no limits to the amount of killing l that is allowed on grouse moors, even in what are supposed to be National Parks.

The important question, that still needs proper public debate, is why any control of foxes is required. While foxes take newly born lambs, eggs and chicks of ground nesting birds, this predation takes place in a very short period and its impact is limited by the fox population on grouse moors (and the uplands more generally) which is generally constrained by the availability of other food sources. All lethal control does is reduce the fox population for a limited period until other foxes move in (see here). While this helps boost the numbers of red grouse that then get shot by humans, waders survived successfully for thousands of years in the presence of foxes.

And if people are concerned about foxes, then the evidence shows that lynx help keep them on the move, just as the presence of foxes deters the protected pine marten from wandering too far from woodland. The way to help waders is not to try and remove predators from the food chain, its to add to the mix.

In the light of these arguments it is reasonable to conclude the noise from landowning organisations about a ban on snares ending country life as we know it, was designed to distract attention from the bigger issue. In that the gamekeepers and land managers have been remarkably successful. The WMMB did not even create any new requirements to report on just how many foxes are being killed each year, not even in our National Parks.

Protection of raptors

While it is still acceptable to cull foxes to increase grouse numbers, the Werritty Review was built on an acceptance that the effective protection of raptors would inevitably result in a reduction in grouse bags. Section 6 of the WMMB amends the Wildlife and Countryside Act to introduce a new licensing scheme for certain game birds (this currently only includes red grouse). The provisions of the bill allow this license for shooting red grouse to be suspended or revoked but without setting out any further details of how this should operate.

These provisions may serveas a greater deterrent to raptor persecution than the powers NatureScot currently has to restrict the General License, which allows landowners to kill certain bird species including some which predate on grouse nests, without permission. At present, after lots of public pressure, four such General License restrictions are in place (see here). On the other hand, because NatureScot’s new powers directly challenge the right of landowners to shoot grouse, they are probably more likely to be contested in court than restrictions on the General License.

This points to the fundamental flaw behind the whole proposal, it is not resourced. The Revised Financial Memorandum to the Bill (see here) describes the main costs as being the creation of a new online licensing system. There appears to be no additional money for enforcement, whether to investigate cases of missing raptors, let alone pay for court cases. Instead, it appears NatureScot’s existing licensing team will be expected to absorb the existing workload. That is not a sound base for potentially trying to legally challenge some of the richest people in the world.

It will be very surprising therefore if more than a couple of estates had their grouse shooting license suspended in the first few years of the scheme. It will be even more surprising if those affected do not use highly paid lawyers to find legal loopholes to allow grouse shooting to continue (e.g. through nominal changes in ownership or management enabling an application for a new license)

On the positive side, the requirement for license applicants to provide maps and for NatureScot to report on the operation of the licensing scheme should provide much better information on the extent of intensive grouse moor management than currently exists. Moreover, the possibility of further game species, such as pheasant or red legged partridge, being added to the licensing scheme in future may act as a further deterrent.

Muirburn

The worst part of the WMMB is the licensing scheme for muirburn which could help legitimise what is a very environmentally damaging practice. Peatland provides the most effective medium term means we have to re-absorb some of the carbon released into the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels and should provide a far more secure means of doing so than woodland which exists over far shorter timescales.

The WMMB bans muirburn on peatland, except for four specified purposes: restoring the natural environment (?!); reducing the risk of wildlfire to habitats; reducing the risk of wildfire to people; and research. Peatland, however, is defined as ground with peat over 40cms deep, the same definition as currently adopted by the forestry industry and which is allowing organisations such as BrewDog to cause such damage (see here). The licensing scheme therefore allows grouse moor owners to continue burning peatland less than 40cms deep for the purposes of producing more red grouse.

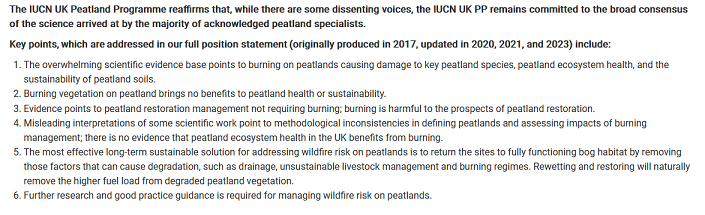

The damaging impacts of muirburn is well described by the IUCN (see here):

The message is we should not be burning the best store of carbon we have. The lack of joined up thinking by the Scottish Government in this respect was well illustrated by the latest report from the Climate Change Committee, issued the day before the WMMB was passed (see here). Basically Scotland is failing to meet its climate change targets, including those for peatland restoration. We simply cannot afford to allow muirburn to continue but instead the Scottish Government has committed £250m to finance grouse moor owners like King Charles to restore peat bogs on the one hand (see here), while letting them burn peat 40cms deep or less on the other. In policy terms this is , is completely incoherent.

The new legal definition of peatland also misses the most important point. It is shallow peatland that offers the most potential to absorb carbon over the next 1000 years. That is because most peatbog development is eventually constrained by the forces of gravity. This eventually causes peatland on sloping ground to slump and break-up. Shallow peat should be valued as highly as deep peat because of the greater potential it offers.

While the 40cm definition presents a slight improvement on past guidance, which defined peatland as being over 50cms thick, most current mapping has been done on the basis of the earlier definition:

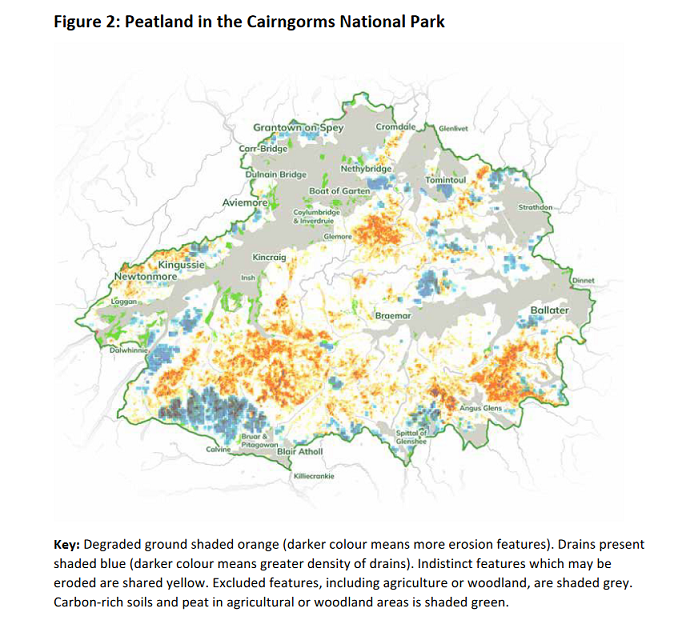

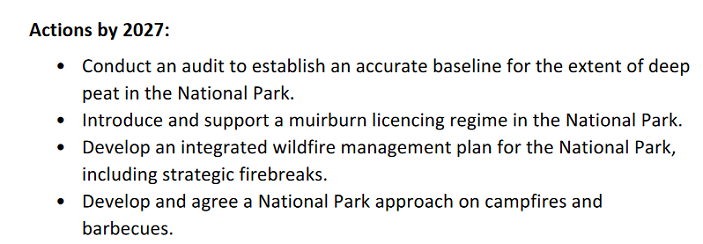

Unfortunately, without maps which accurately show the locations of peatland over 40cms, and without extra resources to do this work, it will be very hard to enforce the provisions of the licensing scheme. Such maps are a long way off even in our National Parks:

There are, however, two potential areas for hope in respect of the management of muirburn.

The first is that the WMMB makes the granting of a muirburn license is subject to the following provisions:

(i) the making of muirburn is necessary for the specified purpose, and

(ii) no other method of vegetation control is practicable, and…………….”

With heather cutting machines now being widely available and some machines having bailing capacity which can be used to create firebreaks, there is little justification for muirburn to continue. Pressure now needs to be exerted on NatureScot to make heather cutting rather than muirburn the norm.

The second area for hope is that the WMMB gives Scottish Ministers the power to change the definition of peatland by regulations.

Grouse moor management and 30 by 30

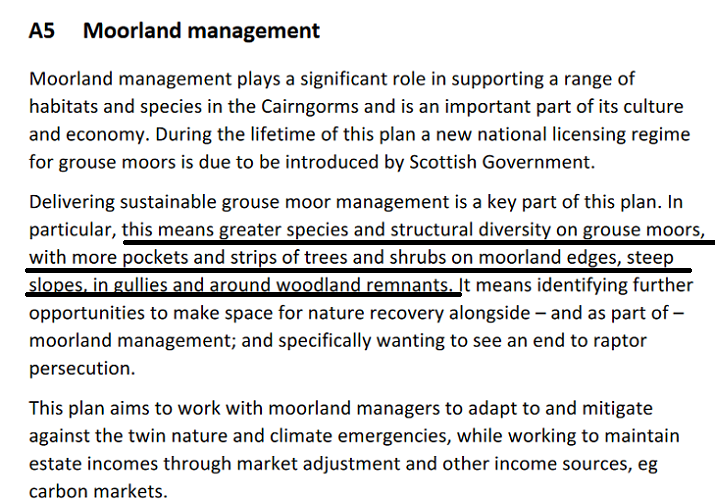

The Scottish Government is committed to trying to protect 30% of Scotland for nature by 2030. With grouse moors making up a large percentage of the land in Scotland – the amount is disputed but somewhere between 10-20% – one would have thought restoring nature on grouse moors would be a priority, particularly in our National Parks which the Green Minister responsible, Lorna Slater, sees as a keen means of delivering that target.

Unfortunately, not only does the WMMB allow most of the current practices that are so destructive to wildlife on grouse moors to continue, it contains no provisions that would help diversify how grouse moors are managed or force owners to set aside some of the land for nature.

The WMMB therefore contains nothing that will help the CNPA achieve its pocket-sized conservation objectives.

The Royal Family’s grouse moors

Delnadamph, which was bought for King Charles when he was a Prince, is one of the most intensively managed grouse moors in Scotland, while much of the land at Balmoral is also managed for grouse (see here).

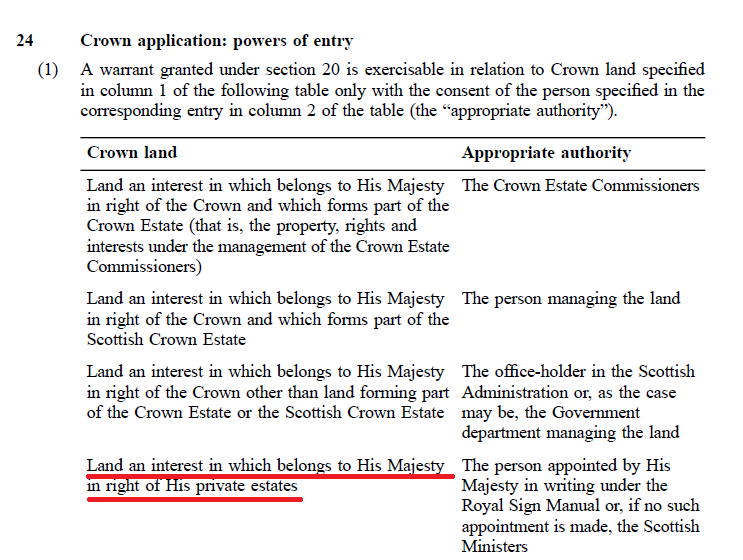

Were a raptor to disappear on royal land – and this had happened on the boundaries of Delnadamph in the past – instead of authorised authorities (who now include the SSPCA) being able to enter the land to investigate, they first need to permission from someone nominated by King Charles:

It says something about the continued power of the Royal Family that the Scottish Parliament could ever agree to such a clause.

Where next?

This post has argued the WMMB Bill is fundamentally flawed – as Revive said, the Scottish Parliament has a lot of catching up to do- and is likely to do little to address the climate and nature emergencies. While the Bill contains monitoring provisions, we simply cannot afford to wait yet another five years – i.e. to 2029 or beyond – to see whether it is having any beneficial impacts.

In the short-term the amount of difference the WMMB will make will be dependant on the detailed provisions of the licensing schemes, which have still to be agreed/designed, and the amount of resources available to ensure their provisions are respected and enforced where necessary. There is still a lot to campaign for. In my view Revive now needs build on the excellent campaigning that has been mainly supported by the animal welfare organisations and expand its membership to include a wide range of organisations which have an interest in regeneration of the land and nature.

Equally important, however, is that with grouse moor reform unlikely to deliver any change quickly, is that conservationists focus on the Scottish Government’s for the reform of the management of Red Deer. Their consultation on that closes at the end of the week (see here). The key point here is that having apparently decided in principle that it is acceptable for grouse moor owners to continue to trash between 10-20% of the land in Scotland in pursuit of grouse, if the Scottish Government allows the same for stalking estates it has no chance of meeting its 30 x 30 targets.

The most important immediate implication of the WMMB is that both the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament need to take a far more radical approach to the control of deer numbers in Scotland.

it’s a tiny crack in the ‘VED’, but it’s still a crack.

I must revise my understanding of fire seeing as the Bill has introduced some spurious limit of 40cm of peat depth on which Gamekeepers can burn peat.

What utter baloney!

I doubt if any Gamekeeper will ever take a ruler out and ensure that a swathe of ground contains only peat of up to 40cm.

If this is the quality of legislation we are enduring from this hapless Administration, heaven (or whatever spiritual place your belief gives you…note to self: ‘must ensure there’s no discrimination here!’) help us when it comes to other significant issues.

As for the Royal estates. Well if this Administration convinces itself and the majority that Self-rule is the way forward, we’ll be ditching the Crown, it’s lands and all the extortionate costs of maintaining such an anachronistic vision of society and they’ll not be a problem. Until then, we’re ham-strung by the offensive ability of the Crown to exclude themselves from the scrutiny that the rest of the landed gentry should be held by.

…..but then, again, what can we expect from an Administration that has a record of being able to shout from the political gallery and pretend to being a government in waiting but have a near absent record on being able to affect anything other than failed contracts, nonsensical legalities about hate and a denial of what constitutes the sexual identity of a woman.