It’s now three years since the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) approved the new planning application (see here) for the financial gamble that is the Cononish goldmine. After it was reported in December that the mine was fully funded until 2022 and the first gold from the mine had been poured (see here) – there had been similar publicity back in 2016 (see here)! – first the Chief Executive, Richard Gray, stepped down in February (see here). Then, in April, Scotgold, the owners of the mine,raised another £1.6m in working capital before announcing more will be needed (see here). Clearly the mine wasn’t as fully funded as had been reported.

In the last year Covid-19, technical issues and shortage of appropriately qualified staff (so much for the claims the mine would bring jobs for locals) have all been blamed for the delays in production which have eaten up working capital. The challenge for Scotgold is to use the lure of gold to keep investors betting more. The betting odds are reflected in the share price, which five years ago had been less then 0.5p, rose to a high of 167p a year ago before dropping to around 50p. That the LLTNPA, which has a statutory duty to promote sustainable development and conservation, chose to value casino capitalism over the natural environment must rate as one of worst planning decisions ever to be made in Scotland.

In approving the application, the LLTNPA made a couple of gambles of its own, that the proposed plans were sufficient to mitigate the environmental damage to acceptable levels and that Scotgold would abide by them. In return it secured £268k, a paltry amount, to “improve” Cononish Glen – mainly through tree planting.

To be fair to LLTNPA planning staff – who were put under huge political pressure to approve the application – they knew this was a huge gamble. To mitigate the risks they issued an extensive list of planning conditions and put in place a Section 75 Legal Agreement to secure these. This included provision for a restoration bond of £538,000, in case the business went belly-up before the proposed restoration plan could be completed.

The LLTNPA also required Scotgold to pay for independent (monthly) monitoring reports which, in a welcome move, they have been publishing on their planning portal (see here) (albeit six months after receipt):

In my view the major issues are still to come, when the mining proper starts and Scotgold begins to try and mould the rock waste into stacks that appear like glacial moraine (see here). But there is already good evidence that the original plans approved by the LLTNPA Board were not fit for purpose and that the environmental damage from the development will be significantly greater than was claimed three years ago.

The destruction of peat

In December 2019, after discussions with the LLTNPA, Scotgold created a temporary 6 month store for “excess” peat from the area where the giant mining shed was being constructed. At the same time it lodged a planning application to legitimise this. The Planning Application (see here) was eventually approved by LLTNPA officers under “delegated authority” in February 2021, i.e 8 months after the peat was supposed to have been removed. It granted permission for the peat to be stored for a further 6 months, i.e until August 2021, after which time the storage area is due to be restored. Ten days ago I went to have a look.

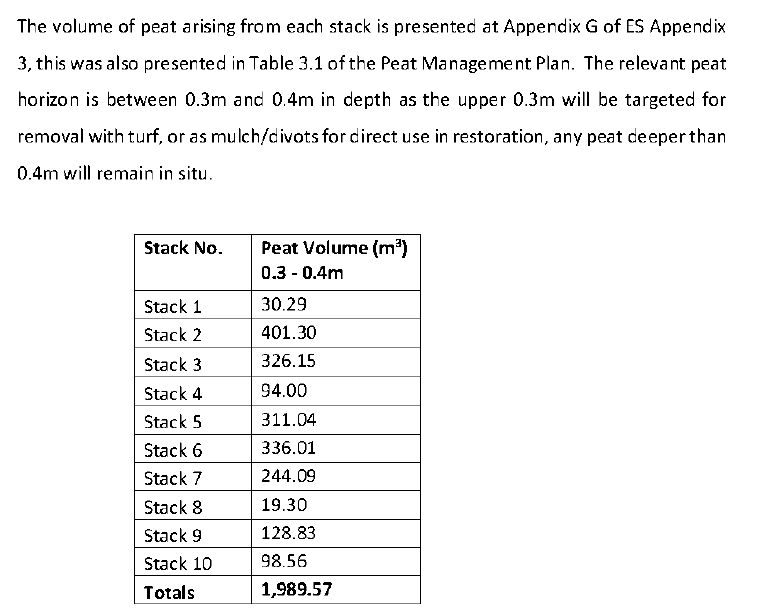

The main Planning Application for the mine was approved on the basis that disturbance to peat would be minimal, except at the bases of the ten waste stacks. There, peat was to be removed and then re-used according to a detailed Peat Management Plan:

Unfortunately, the LLTNPA had failed to ensure proper surveys of peat in the area near the Eas Anie where the giant shed was to be constructed. The Planning Application was to “store” up to 7,300 cubic metres of peat, 3.5 times the amount estimated for the stacks. That represents a large amount of carbon. Had the volume of peat on site been made public three years ago, it would have been much harder for the LLTNPA Board to give the go ahead to the mine.

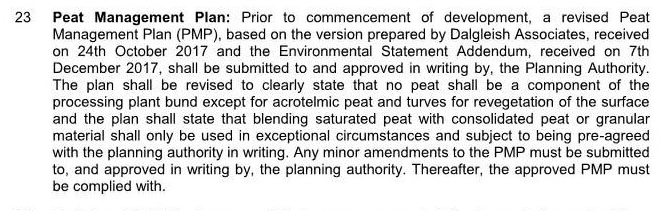

The planning consent granted by the LLTNPA Board required Scotgold to produce a Peat Management Plan and explicitly prohibited the use of peat to “restore” the bare surface of the bund surrounding the shed:

This was made for the very good reason that “a peat bund of this size and slope would not be appropriate for permanent or long-term landscaping as the peat would dry out and lead to potential erosion”.

The LLTNPA’s report of February makes no mention of this requirement. Instead it reversed the LLTNPA’s original position by giving the go-ahead to Scotgold to use the peat to restore the slopes of the bund:

“The peat found within the footprint of the plant platform and bund area required to be removed in order to expose rock for construction and in accordance with the planning approval for the mine, the removed peat was to be used progressively in restoration”

Part of the problem of what to do with the embarrassing excess of peat, as the top photo shows, solved…………use it like the peat garden compost which campaigners have been trying to ban for years!!

According to the planning application, the other main way that the excess peat has been used has been to restore the access track, i.e as more garden compost:

“The total volume of peat temporarily stored at the application site was 2,377 m3. 1,073 m3 of this peat was used in improvements to the Cononish access track and in reinstatement of passing places and 745 m3 was returned for restoration of the plant platform and bund”

Just why the application was to store up to 7,300³ metres of peat but only 2,377³ metres was stored is not explained. It seems likely that some of the peat extracted from the platform area was used in “restoration” works immediately, without the need for any storage.

The peat storage facility

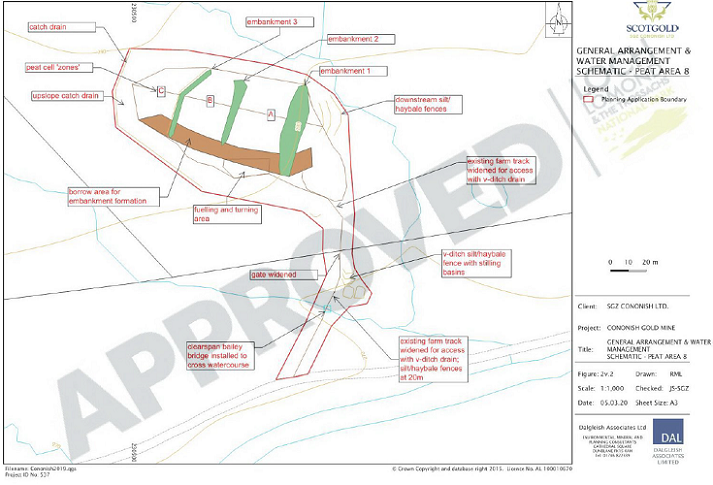

The temporary temporary peat storage area lies outwith the planning boundary for the mine, below Cononish Farm and in a “dip” in the landscape. Originally three “cells” were planned in which to store the peat:

In the event Scotgold only excavated two (A and B) and has only used one (A). That lends support to the idea that when the amount of excess peat first became apparent, the LLTNPA’s initial reaction was to stick with the planning conditions about how peat could be used on site. With nowhere to use it, their only option if the mine was to go ahead was to create a large storage facility while they figured out what to do next. Unable to come up with any other options, they then decided to relax the requirements of their peat management plan.

In creating this large pit, which has so far never been used, yet more peat was excavated and moved.

The most recently published monitoring report for the mine, from last October, clearly stated Scotgold had failed to comply with the turf management plan: “Storage of turves has not been in a single layer on tarp/geotextile”. Over six months later, the LLTNPA and Scotland appear to have done nothing to address this failure.

While the remaining peat in storage cell A is being kept wet, which helps prevent it disintegrate, a considerable surface area is exposed to the atmosphere, where it reacts with oxygen and steadily releases Carbon Dioxide into the atmosphere.

The evidence suggests the way that the “excess” peat at Cononish has been stored and moved is contrary to the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency’s statement of good practice (see here). The main issues are:

- the longer peat is exposed to air, the more it degrades and much of the excess peat, whether on the slopes around the mine or in the storage area has now been exposed for 18 months;

- use of the excess peat on slopes and roadsides is very unlikely to re-create bog habitats which might preserve the peat, but instead treats it as a form of compost which will rapidly dry out and break down releasing carbon into the atmosphere.

The way the LLTNPA has managed the excess peat at the Cononish goldmine is a mini-environmental disaster and makes a mockery of its claims to be committed to restoring peat bogs. This sentence from the planning report indicates the LLTNPA’s priorities:

“The requirement of a peat storage area outwith the mine site is supportable in principle as it will enable the continued development of the mine”. Anything is allowed when it comes to keeping casino capitalism going.

The settling pond

One of the areas where some of the excess peat may have been used is around the new settling pond at the bottom of the mining area:

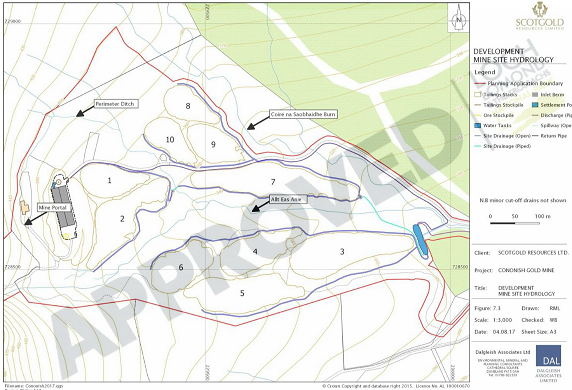

I checked the main planning application after my visit and was unable to find anything about the design of the settling pond, only this map:

The Planning Monitoring reports indicate that the design and location of the settling pond have changed since the original application. There is nothing on the planning portal to show how this was approved (normally planning officers would either consent to a “Non-Material Variation” or require a new planning application to be submitted). This represents another big hole in the planning process. Without agreed plans, there are no planning conditions to be enforced and, when it comes to restoration, it will be anyone’s guess as to what should be removed from the site. My bet is that this settling pond, with its rip rap bouldering, stone vetements and suburban-type landscaping will never be restored.

What needs to happen?

Had planners in the Cairngorms National Park Authority been presented with a request to create a storage area for up to 7,300m³ of peat, or change the design of a settling pond in the way that has happened at Cononish, there would not only have been a planning application, it would have been decided by their Planning Committee. But in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park decisions which have significant implications for its statutory aims are deliberately delegated to officers.

In the whole of last year, the LLTNPA Planning Committee considered just six separate planning applications and one tree preservation order. Every other planning application was decided by staff, or rather by the senior managers who control everything that happens in the National Park.

The shameless hypocrisy of some of those senior managers is striking, claiming one thing, but doing another. While spinning to the public and Scottish Ministers – Scotland’s peat bogs “are the best carbon store we have so it’s vitally important we look after them” (see here) – at Cononish they have quietly dropped the planning conditions that were designed to protect peat. The LLTNPA Board needs to take back control. A first step would be to revise their standing orders so that any planning application that has significant implications for the natural environment is decided by Committee. At least then there might be the opportunity for some critical scrutiny, even if current Board Members have so far appeared reluctant to do this.

LLTNPA Board Members should also hold senior staff accountable for allowing the destruction of such large quantities of peat at Cononish – but don’t hold your breath!

Makes a mockery of the Scottish government pledge to be world leaders in combating climate change

Did you actually believe her? Words are wind.

A restoration bond is virtually worthless unless it is regularly reviewed and revised. Simply put, a restoration bond of £538,000 approved three years ago no longer buys the same amount of actual restoration work. Costs always go up. Unless the bond is increased with inflation it wont deliver. The Scottish Government planners no longer recommend the use of fixed bonds largely due to the disaster that unfolded with the collapse of the opencast coal industry.

I think you are right about this. There is provision for the LLTNPA to review the level of the bond but so far they don’t appear to have done this. Looking at the settling pool, I could not help thinking that to restore that properly might well eat up a large part of the budgeted amount.

The small print of the planning approval may include a review of the bond provision…if it does not then the destruction will be permanent. If the mine goes bust or when it closes….the last thing on the mind of the directors will be ensuring there is a huge wad of cash being reserved for the clear up. Once the company is liquidated…its responsibilities go with it.