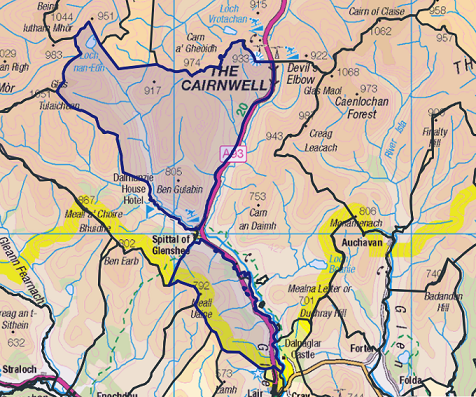

I spent a couple of days this week on the Rhiedorrach Estate, east of Glen Shee. Walking up to the lovely Loch nan Eun to camp, we only came across this trap because the river was so low we decided to boulder hop across it opposite the Dalmunzie hotel. Two days before we had come across numerous traps – all empty – around Rhiedorrach, half way along the A93 between Spittal of Glen Shee and the Cairnwell.

The traps are particularly unsporting. Weasels specialise in hunting small rodents and their long slender bodies and short legs have evolved to enable them to search through tunnels and runways of mice and voles. They are instinctively drawn to holes, hence the tunnel traps which give them no chance.

Weasels are one of the forester’s best friends because they help keep the vole population under control and enable tree seedlings to become established. They also occasionally find and eat the eggs of red grouse and other game birds. Because of this weasels are treated by sporting estates as vermin. If they were not so persecuted, we would not need all those plastic vole guards that pollute the environment.

In recent years, in order to justify their continued existence, sporting estates have increasingly claimed that the survival of ground-nesting birds on moorland is a consequence of “vermin control”. The East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership, which includes Invercauld Estate and Balmoral, has been particularly successful in persuading the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) that “Breeding waders have declined across the UK due to predation” (see here).

It is true Glen Shee is a wonderful place for waders, from the low ground where the bubbling sounds of adult curlew were pervasive this week to the golden plover on the high tops. It would be a mistake, however, to believe that this is a consequence of all the traps. Weasels and stoats rob bird nests, of course, but they have co-existed with wading birds since the last ice age. This is one of those awkward facts that the advocates for killing off predators to protect ground nesting birds need to explain.

The truth is far more complex. Weasels and stoats, like pine martens, are themselves predated on by foxes and birds of prey. They therefore use the cover of features like walls and hedges to move around their territories. That is why two of the traps featured in this post were found on walls. The number of weasels, therefore, and their impact on waders depends in part on the population of other predators which just so happen also to be mercilessly persecuted by sporting estates.

There is also the complex issue of population cycles and an extensive literature on the relationship between the vole population, weasels and the impact on other species. Suffice to say that if natural processes were functioning without human interference in some years more wading birds (and more grouse) would be be predated by weasels than others. That, however, is not allowed to happen in the eastern part of what is supposed to be a National Park.

This year the number of voles in the eastern Cairngorms has exploded (thanks to NTS staff at Mar Lodge for confirming this). I don’t think I have ever seen so many walking over the hill. It is not just the weasel population which will do very well. High up at Loch nan Eun on the western edge of the Rhiedarroch Estate we watched a short-eared owl in the gloaming attracted by all the bounty.

This year the number of voles in the eastern Cairngorms has exploded (thanks to NTS staff at Mar Lodge for confirming this). I don’t think I have ever seen so many walking over the hill. It is not just the weasel population which will do very well. High up at Loch nan Eun on the western edge of the Rhiedarroch Estate we watched a short-eared owl in the gloaming attracted by all the bounty.

Meantime, however, despite the babbling calls of the adult curlew, it looks like being a catastrophic breeding season for waders. The main reason for that has nothing to do with any increase in the weasel population but with drought:

The extremely dry conditions have made it very difficult for birds that probe beneath the surface for food. Most of the boggy places have dried up and much of the ground is now rock hard, impossible for bills to penetrate. Without food there are less eggs and few if any of the chicks that do hatch will survive. Weak adults and chicks then also become more vulnerable to predation but that is incidental to the main issue.

What is driving these problems for waders during the breeding season is not weasels but humans. Global heating and the extreme temperatures we have seen pose an existential challenge to species that depend on wet places. Those impacts caused by our consumption of fossil fuels have been massively increased in upland areas by the way the land is managed for sporting purposes.

That was evident as we walked up from all the traps around Rhiedorrach house to Carn a’ Gheoidh.

Most of the bowl through which the Allt Coolah flows down to Rhiedorrach, like the rest of the upper section of Glen Shee, is subject to intensive muirburn. Burning the steeper slopes increases the rate that water runs off the hill and means the amount of seepage into the boggier areas below is greatly reduced helping them to dry out more quickly.

Muirburn also leaves the ground exposed to the sun speeding up the rate at which it dries out:

These problems are accentuated where the numbers of grazing animals (voles, hares, sheep and deer) which feed off the more palatable grasses and flowers which colonise the bare ground first are high.

The high numbers of deer and sheep on Rhiedarroch is delaying vegetation recovery from muirburn and their trampling then accentuates the problem further:

The impact of trampling was highly visible in the eroded and dried out peat bog below:

The consequence of this sporting management is not just that carbon is being released from the peat bog into the atmosphere, it is destroying the boggy areas on which waders depends.

The irony is that young grouse chicks, like waders, feed on invertebrates and this desiccation of moorland through muirburn and overgrazing is not good for them either.

Rhiedarroch was formerly part of the Inverauld Estate but sold in 2018 and is now owned by Rhiedorrach LLP controlled by Wayne and Heather Johnston.

The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) estate map (see here) still shows Invercauld as the owners – why is it they cannot even keep up with who owns the land? The CNPA had no power to vet the suitability of the new owners before they bought the land and there is no still no new estate management plan showing how the land is being managed. I would suggest the name, Rhiedarroch Sporting LLP speaks for itself and is contrary to the statutory aims of the CNPA the first of which is conservation.

What needs to happen

Currently, the CNPA devotes far more effort to predator control as a means of “saving” wading birds than its does to addressing the destructive forms of land-use that continue to destroy the habitats on which they depend. While the drought in the east may end next week, that is likely to be too late for breeding waders this year. The disaster reinforces the argument that the real issues which the CNPA should be tackling are muirburn and the high numbers of grazing animals.

The Wildlife Management and Muirburn Bill (see here), which is currently being considered by the Scottish Parliament, won’t as it is currently drafted address most of the issues considered in this post. Requiring gamekeepers who set traps to go on training courses will do nothing to stop the carnage.

The Bill explicitly allows estates to continue to burn the land for sporting purposes as long as it done in accordance with the muirburn code and as a result the destruction of wader habitat will continue. The Scottish Parliament’s Rural Affairs Committee could do worse than ask Scottish Government officials to map the current extent of muirburn on estates like Rhiedarroch and show what they expect to change if the bill becomes law.

Unless the bill also addresses the interaction between the numbers of grazing animals and muirburn on estates like Rhiedarroch and Invercauld, which are managing the land for both deer and grouse shooting, the adverse cumulative impacts of multiple sporting use will continue unabated.

On the ideological level,conservationists need to start to challenge the cultural assumptions that have been created by sporting interests. On the one hand Red Squirrels, the robbers of tree nesting birds, are portrayed as cuddly and as an iconic species by our National Parks among others, while on the other hand they allow the weasel, equally cheeky and entrancing, to be ruthlessly persecuted.

That weasel, ruthlessly flattened, was once as beautiful as any red squirrel and should have an equal right to exist in the Cairngorms National Park.

I think that every one of your photos showing muirburn contains some form of violation of the “code”. The shooting estates have shown little respect for the code…..mere guidelines. Their defence is easy…the code is vague and open to interpretation. It will be impossible for the new licencing system to rely on adherence to the code. Unless the code is redrafted and tightend/clarified it will make bad law.

It would help if the law was rooted on functioning ecosystems rather than birds or peat.

The classic operation of the Victorian-Edwardian Dystopia regime

Great article I have seen traps in the hills as well. Needlessly bleak hill ground, as you say we need real working land legislation in Scotland.

The sporting estates must be doing something right for conservation because if you look ex grouse moors the RSPB have taken over they are no more than barren landscapes with very little wildlife.

Hi Robert, I would be interested in seeing the evidence on which this claim is based, Nick

That is not my experience at all. To which ‘ex grouse moors’ are you referring?

I think he is referring to how grouse numbers tend to go down on RSPB managed land, so you get a more diverse, healthy and slowly recovering ecosystem that for the untrained, paid by shooting estates hunter that doesn’t know how to track, eye might look like a wasteland, most other people call them forests and moores where not every living being is there to be shot at, truly a new concept for these people. Probably that is why he couldn’t provide information