In January 2020 I wrote a post (see here) about the LLTNPA’s consultation on “Active Park, Healthy People”, parkspeak for what had been an Outdoor Recreation Plan, and said this about paths:

“Paths are crucial for outdoor recreation and – whether you agree with the spin or not – for the delivery of the LLTNPA’s stated ambitions. The “plan” refers to the work done by the Mountains for People project on paths over the last five years but says nothing about what will happen now that funding is coming to an end. The fact is that apart from funding for cycle paths from Sustrans, there is now NO core funding available either to create new paths or maintain existing ones. That probably partly explains why the Park’s Core Paths Plan was so lacking in ambition (see here) but leaves an enormous hole. So, why has the “plan” not addressed this? And what, for example, is Forestry and Land Scotland going to invest to make up the difference?”

The disappearing outdoor recreation plan

The last Outdoor Recreation Plan covered the years 2012-17 and, as Mary Jack pointed out on parkswatch (see here), was already well out of date by the time the consultation ended in January 2020. As one of the respondents, in early March 2020 I received an email say the final plan would be considered at the June Board meeting and not March as previously announced. That didn’t happen due to Covid.

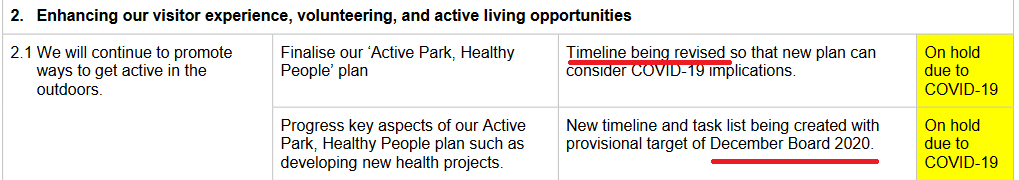

At the September 2020 Board Meeting it was reported that the work was still on hold and the timeline was being revised :

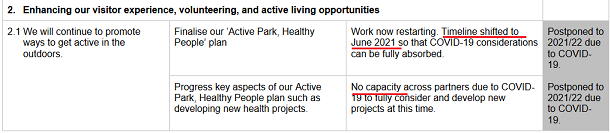

Then, at the December 2020 Board Meeting, there was what appeared to be some good news:

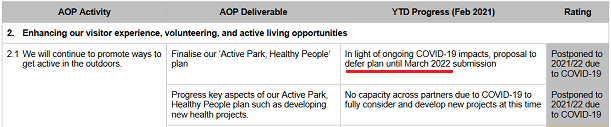

However, just three months later in March 2021, it was reported that the plan would be deferred another nine months until March 2022, again due to Covid:

The latest deadline for the new plan is now five years after the last one expired, by which time the consultation will be well out of date! Clearly, the system of governance in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) is unfit for purpose.

Since the LLTNPA Board allowed their Chief Executive complete power to decide staffing matters, they have completely lost the ability to influence what the National Park Authority does and doesn’t do on a daily basis, including whether any of their plans are delivered. No-one on the LLTNPA Board appears prepared to challenge their management team about why timescales constantly shift like this or the underlying reasons for this. My guess is that the explanation is that the LTNPA’s Access Team does not have the capacity to do what is needed.

The consequences of these failures for the footpath network in the National Park and outdoor recreation are serious.

The case of the tourist path up Ben Ledi

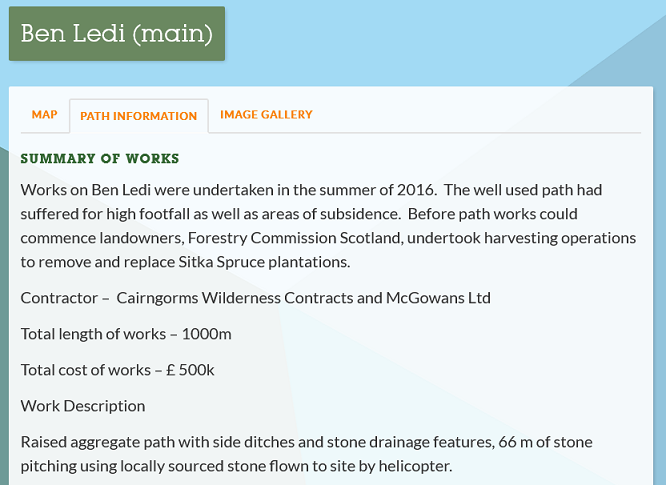

Last month I went with some visitors for a walk up Ben Ledi. It was the fourth time I have been up that hill since 2016, when work was being done to re-align and upgrade the main path as part of the Mountains and the People Project (see here) funded by the National Heritage Lottery Fund:

Five years later, parts of that path work are disintegrating, as evidence by the top photo and those that follow:

Part of the explanation for this path failure appears to lie in fundamental design flaws, particularly on the steeper sections. People generally don’t enjoy walking on hard stone but it is well known in the path world and written into the Upland Path Standards (see here) that where the vertical height difference between steps is more than 15cms people will avoid them if they can. That appears to account for what has happened here and significant section of the new step work on the main Ben Ledi path is at risk of being left high and dry just five years after construction. That in itself should be enough for an LLTNPA Board visit and an inquiry into what has gone wrong.

The maintenance failure

Some of the problems originating from the design flaws could still have been prevented had there been follow-up work and regular maintenance. One of the ideas behind the Mountains and the People project, which was funded for five years, was to train up volunteers to keep the paths in good order. In 2019 Volunteers did some excellent work on the lower section of the Ben Ledi path that was not included in the Cairngorms Wilderness/McGowan’s contract work (see here). However, the last recorded volunteering projects appear to have been in October 2019 and since then not even the most basic maintenance work appears to have undertaken:

The impact of feet – including crampons in winter! – on the exposed plastic culvert will shorten its life signficantly but not even basic maintenance issues such as this are being addressed.

While the path up Ben Ledi from Stank Glen, which was built at the same time by the Mountains and the People Project, is generally in far better condition, it too has been neglected:

I have photos from December 2018 showing the fence intact. With the erosion, the wire is now at just the right height for a child skipping downhill to garotte themselves. It would be almost impossible for anyone to see in the dark. The safety hazard is obvious and would have been picked up if anyone was maintaining this path. But having managed to get all the path work paid for by the lottery, Forest and Land Scotland should not have relied on volunteers to do the maintenance. Indeed the very first principle in the Upland Path standards published by NatureScot states:

“Pathwork will be carried out within a coherent management framework, including a commitment to long-term maintenance. It will integrate with other management objectives”

We need to ask why Forest and Land Scotland have abdicated their responsibilities to the extent that they are not even prepared to check if the paths are free from human created hazards? Tourist Income from the forest cabins below Stank Glen should have provided an easy means of paying for this but they have been outsourced to Forest Holidays who don’t appear to invest anything back into the area. The wider question is why the LLTNPA has not held Forest and Land Scotland to account for these failures particularly when their Convener, James Stuart, is also paid to sit on the Scottish Forestry Strategic Advisory Group (see here).

So how bad is the situation with the two main paths up Ben Ledi?

It is important to put these problems and failures into perspective. Apart from the fence, the path up Stank Glen showed little obvious sign of deterioration since I had last walked it in December 2018 – nothing to cause me to stop and take photos!

There are a number of explanations for this. While at a similar altitude to much of the main path up Ben Ledi, the Stank Glen route has less footfall, is far less steep and is surrounded by native woodland which reduces the amount of water flowing onto it. It is likely to require relatively little ongoing maintenance to remain in a good state.

There are similar sections along the main path which have held up well since construction and where the vegetation on either side has regenerated successfully.

But there are also slightly steeper sections where the aggregate surface has been washed away. According to the Upland Path standards, if properly designed this shouldn’t happen. This has made the path unpleasant to walk on so people have taken to the verges and they are now starting to erode. .

Regular maintenance – a stitch in time – would prevent these problems becoming serious and undermining the £500k that was invested in creating the new path. Some damage to the new path needs to be fixed immediately:

Other damage is less urgent. I was concerned about the abrasion on either side of this short section whic is clearly a consequence of poor path design/construction:

But compared to the situation which I visited in December 2018, while the eroded area has spread slightly its not significantly worse:

What the photos show is that some of the paths that evolved around the steps are relatively robust and have yet, themselves, been subject to serious erosion.

The summit section of the main path

There is also some serious damage to the upper section of path which, as far as I am aware, was not included in the Mountains and the People Project, ie despite spending £500k this was not enough to repair the entire Ben Ledi path, only the middle section:

There had been earlier work done on the upper section of work but, without maintenance and further investment, it has gradually eroded away. Sections are now collapsing:

What needs to happen

The photo above (I have more!) provides an illustration of what is likely to happen to the stepped sections of the Mountains and the People path unless the problems are addressed quickly. That requires Forest and Land Scotland, who own the land, to fulfil its obligations to maintain paths on the land it owns properly and to act to rectify the problems.

The Ben Ledi, path, however raises broader issues about how paths are being repaired and maintained in the National Park which also requires the LLTNP to act:

1) Improving path design. The design faults in the Ben Ledi path should have never have happened. Many people, over many years devoted considerable effort to working with SNH/NatureScot to develop Upland Path Standards, incorporating experience from the past, and these standards are still promoted by the Scottish Outdoor Access Network (see here) Part of the problem – and its not just Ben Ledi – is they are not being applied. Ironically, some of the best examples of the path standards being ignored are in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority – (see here for the Ben A’an path and I will cover another example soon) – which in its early days was very involved in developing them. The explanation for why this has happened partly comes down to lack of money but with that a lack of critical commentary about what is going on. We could do worse then re-invent the British Upland Footpath Awards, which produced critical evaluations of pathwork each year and kept everyone on their toes.

2) Creating a framework for path maintenance in the National Park. Much of the money invested by the Mountains and the People Project and earlier path programmes has been wasted because there is effectively no maintenance of the path network in the National Park. That project trained up a significant number of people to do pathwork but, without jobs to go to, most of the money appears also to have been wasted. The answer is that both Forest and Land Scotland and the LLTNPA need to set up their own permanent footpaths teams. It will take resources, but with the Scottish Government having in their agreement with the Greens signed up to spending 10% of the transport budget on active travel (which should include active tourism), there could never be a better time to create such teams and local jobs.

3) Investment in paths. Our upland paths are under pressure as never before due to the pandemic. That this would happen should have been obvious but if the LLTNPA needed evidence the National Trust for Scotland explained the impact on Ben Lomond almost a year ago (see here). This should have been an opportunity to call for more public investment in paths but instead the LLTNPA kept silent.

The LLTNPA then decided to delay their Outdoor Recreation Plan, which should have been the means by which they could articulate the level of investment required, a missed opportunity if ever there was one. Until that happens, the path network in the National Park will continue to deteriorate but I have my doubts that the LLTNPA is capable of delivering this under their current leadership who need to be held to account for their recreational failures.

The state of some of those footpaths should be of serious concern to whoever is responsible for them. While the majority of people will navigate them safely, it is only a matter of time before someone twists an ankle or breaks a leg requiring mountain rescue, a helicopter attendance or even possibly a life threatening injury! Will it take an insurance claim before something is done to make these paths safe again?

A minor point (and not excusing LLTNPA or FLS) but Scottish Forestry is a completely separate body from FLS (and in any case non-exec advisors have a very limited role)

Sorry, I should have made that clear about SF and FLS but in my view, SF as the regulatory body, should be able to bring some influence to bear on how FLS manages its land. It must, for example, now be in the power of SF to amend the UK Forestry Standards, include in that standards for recreational paths in forests which could incorporate the need for maintenance?

There is an issue here, which is so very similar to the way the public have been regarded as inconvenient pests if they venture into the land areas held by vast “state” facilitated organisations . It would not be beyond the remit for the legislation under which Forestry Land and National parks are permitted to exist ,to be adjusted. Why not legislate for National Parks and Forestry Land so managers must demonstrate use their holding to educate and inform the public? (Near here we have a structure known as the “wood school.” 20 years ago the construction of an open sides classroom was part funded by a local appeal and a visionary forestry project , as part of a wider conservation and regeneration ideal. The roofed wooden structure was built by and for the community to use, under a scheme that recognised the importance of teaching young people to understand and appreciate the forest areas. By holding ecology sessions within the woods it was possible for local schools to bring youngsters, adult groups and visitors to learn about the potential careers locally in forestry operations and view for themselves woodland management in practice.. 20 years have now passed. Those “post holders” who started it all are long gone…Those in authority now, were – most of them- hardly even out of primary school when this exceptional open classroom structure was built. The paper-trail of reasons and community involvement so long ago ( 20 years only ) does not interest them anymore. They see only an administrative and potential cost burden , as well as a perennial risk “problem’. The visionary and significant native woodland regeneration concept,which was officially opened by the Duke of Rothesay still has a vital message at its core. The education potential of these land areas and undeveloped spaces is something , surely, that should be encouraged? In fact if the foresters now in charge left their offices they could not deny the truth . The structure I refer to, is adjacent to a Royally approved teaching woodland…an example of how if allowed to native woodland can recover from blanket plantation. Yet …today ..Forest managers claim the wood school stands within an area that needs to be felled.. in truth it is surrounded by regenerating native tree species on the ‘interface’ with a much more mature commercial plantation! There are now proposals from Forest managers to pull the wood school structure down, unless some local community interest assumes responsibility for it. An outdoor opportunity to use this facility to educate the public about woodland management in Scotland is dismissed ..a group of hard headed university educated forestry managers in total denial?

I wonder if the Lottery attached maintenance conditions to the grants?