Following on from my post on peat bog restoration in Glen Banchor (see here), in 2020/21 three new woodland enclosures were erected along the River Calder as part of a conservation project.

It involved a fair amount of machinery, raw materials (including bags of cement just out of the photo) and materials for fencing. How long it will take the project to recover the carbon expended in its creation is unclear.

It involved a fair amount of machinery, raw materials (including bags of cement just out of the photo) and materials for fencing. How long it will take the project to recover the carbon expended in its creation is unclear.

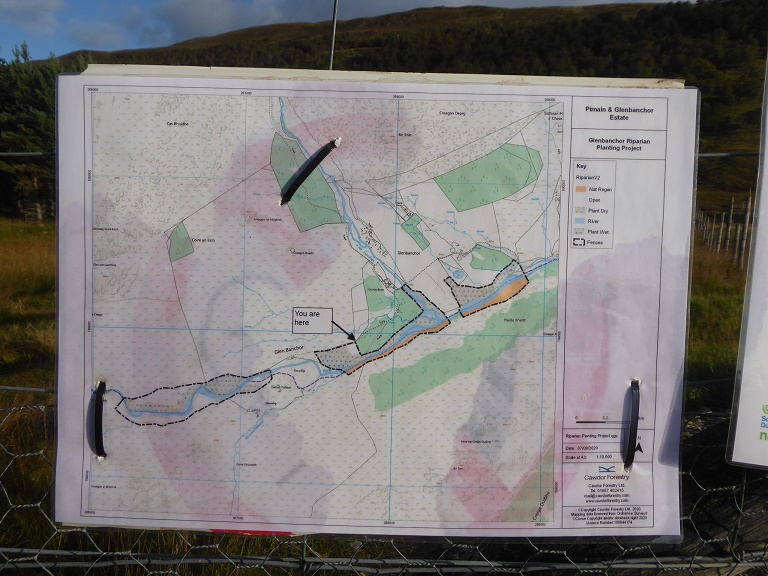

From the start, there was a helpful sign showed the location of the enclosures:

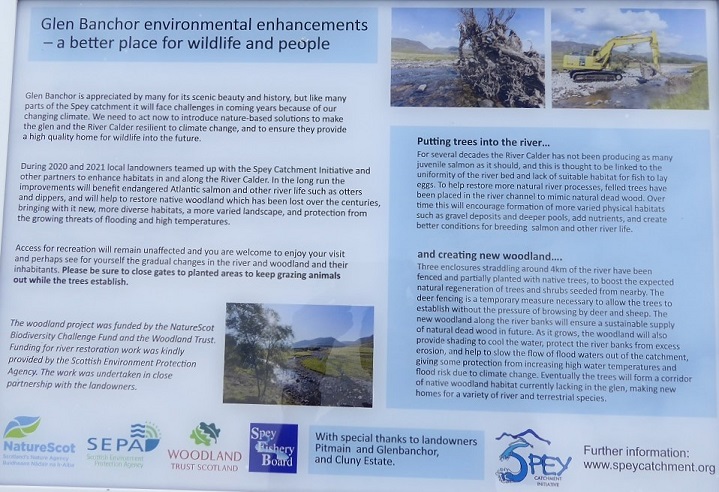

And a number of other signs explained the purpose of the enclosures and of putting dead trees into the river:

This post takes a critical look at the rationale of this project, within the context of the need for landscape scale conservation, and whether it is likely to deliver its stated intentions.

Mitigating climate change?

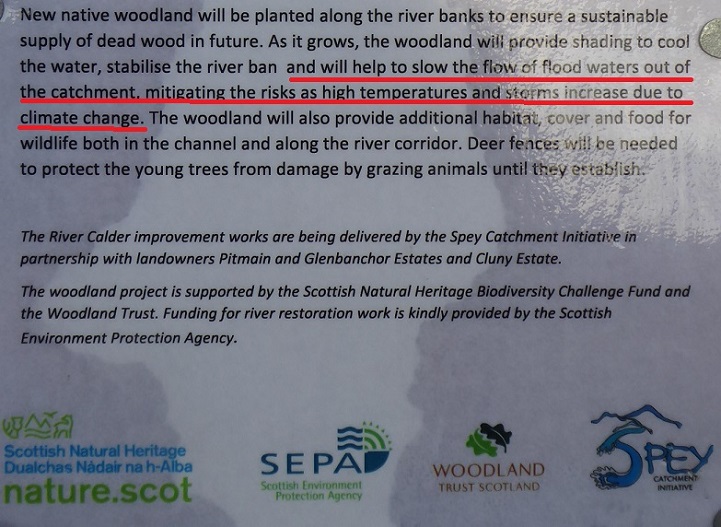

The project claims to be a nature based solution to climate change, with different signs saying slightly different things about this:

Unfortunately there is as yet no publicly available estate management plan for Glen Banchor, only the very out of date woodland management plan featured in my previous post. However, if the woodland enclosures are considered alongside the adjacent peat bog restoration, it certainly looks like this could be part of a concerted attempt to slow down the flow of water along the floor of Glen Banchor in response to the greater rainfall predicted by climate change scientists.

The problem, however, is that by the time water reaches the floor of Glen Banchor it is too late. Conservation attempts need to start higher up the hill (see here), which is why blocking drains on peat bog on the high tops is a good idea. But conservation initiatives also need to tackle the other causes of rapid water run-off, muirburn and overgrazing.

Deer above the Allt Fionndrigh, which flows into the second new woodland enclosure, November 2019.

Fencing as a solution to grazing pressure?

There are plentiful existing seed source for native trees in Glen Banchor and if grazing levels were reduced woodland would regenerate naturally along parts of the flood plain.

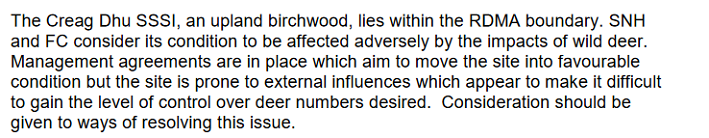

The challenge is that NatureScot (SNH), the public authority responsible for protecting designated sites, has not even been able to protect the Creag Dhu birchwood above the floor of the glen, with the landowners apparently reluctant to take appropriate action:

The landowners reluctance to co-operate is confirmed by this further comment from the Plan :

“It is unlikely that the current ‘condition’ of such features [i.e SSSIs etc] can be improved easily without a drastic reduction in deer numbers or the installation of deer fences to ensure complete exclusion. Heavy culling will always cause difficulty with owners trying to deliver multiple objectives (see here)”

Hence why the new enclosures are needed to enable natural regeneration, one of the declared purposes of the project. Even if this works, it will leave an overgrazed gap between the new river woodland and the Creag Dhu birchwoods above. In other words patchwork rather than the landscape scale conservation..

The exclusion of all large grazing animals, however, creates another “problem”, especially on the more fertile ground along the river. The vegetation quickly becomes luxuriant making it very difficult for tree seed to become established. So, because conservationists are in a hurry and want to be seen to be doing something they plant trees. Whereas if some larger herbivores were able to access these areas, their browsing would help create gaps in the vegetation while their feet would help break up the ground.

Again, this is hinted at in the Monadhliath Deer Management Plan:

“Fencing will, many would argue, lead to an unnatural habitat developing and also may require compensatory culls to be taken. That said, in the long-term fencing should always be as a temporary measure ideally – deer should ideally be allowed back into a fenced area once recovered, so that a more natural balance can develop across the feature as a whole”.

It would be interesting to know if NatureScot has required compensatory culls in this case but the failure to tackling the grazing issue more generally not only pushes conservationists into erecting expensive ugly enclosures, it also forces them into gardening.

Will the fencing plan work?

The signs suggest the fencing is particularly robust, so possibly it will last longer than the usual 5 – 10 years. While the claim that the fencing is intended as a temporary measure may be true, the expressed intention to create “sustainable” woodland which will help nature in the long-term appears to me pie in the sky.

The evidence for this can be seen in the existing native woodland plantations on the Glen Banchor estate side of the river, some adjacent to the new enclosures:

The explanation for this state of affairs is simple:

With grazing animals being kept inside old enclosures and free to wander in large numbers around the new ones, it is 99% certain that the new woodland planting will not achieve its desired purpose and be able to perpetuate itself without fencing.

Is this conservation or public support for private sporting interests?

In the last few years, putting dead trees into rivers to try and alter their flow and create wildlife habitats has become very fashionable (the RSPB are currently doing this in the River Tromie). Unlike many other conservation initiatives – such as the use of herbicides around planted trees – there appear to be few adverse consequences, although if the large tree trunks were dislodged by a flood they could potentially do significant damages to bridges and other infrastructure downstream. Putting trees into rivers is also easy to do because landowners and their agents are unlikely to object to anything that might improve the fishing at public expense.

Instead of SEPA paying for this, why weren’t the very rich Jaffar family, who own the Glen Banchor estate, not asked to transport up some of the windthrown trees from their land near the end of the public road (see here)? Or perhaps they were asked?

Viewed from a critical perspective, ALL the alleged conservation work in Glen Banchor is at best designed not to challenge the interests of the landowners and at worst is pro-actively subsidising those interests:

- The new native woodland along the river may improve the fishing but if not will provide additional shelter for deer in winter in the medium term helping the estate to maintain high numbers of stags for shooting.

- Instead of using the offer of public investment to secure a reduction in grazing levels, the estate appears free to continue to farm sheep and manage deer as it wishes. This will negate any possible positive impacts this project might have.

And to rub salt into the wound, the estate has been allowed to develop new sporting infrastructure adjacent to the peatbog and woodland restoration projects:

Why the Woodland Trust ever allowed itself to become associated with such a project is unclear. Perhaps it was because for NatureScot to dish out public funding a partner was required and Glen Banchor refused to contribute?

Ironically, the solution to overgrazing by livestock is being practised in one of the areas between the new woodland enclosures but only for cattle:

If sheep were managed in this way, that would really help both native woodland regeneration and to protect areas of peat bog.

The mis-use of public funds for private benefit

On 22nd December 2022, hidden away just before Xmas, NatureScot published a list (see here) of payments of sums over £25k it had made in 2021-22 (as required by the Public Services Reform Act). It included:

| PITMAIN AND GLENBANCHOR LTD | 28174 | 1188554 | 22-Apr-21 | 64,521.16 | ERS-12732-91053 | |

| ERS-12731-91052 | ||||||

| 1188910 | 13-May-21 | 34,345.00 | ERS-13069-94043 | |||

| Total No: 2 | Total No: 3 |

A Freedom of Information request, seeking details of this payment and any others made to the Pitmain and Glen Banchor estates will follow..

Whether or not paid for this project, this comes to a sum of just under £100k paid to an estate apparently owned by the Jaffar family, one of whom Majid Jaffar is Chief Executive of Crescent Petroleum. Crescent is the largest private oil company in the world and therefore bears a significant degree of responsibility for the changes in climate that are threatening more destruction on Glen Banchor. Instead of demanding that this family do their bit to restore woodland and peat bogs, as a condition of owning land in Scotland, the Scottish Government is through its agencies forking out public money to them. Not only that, those agencies are allowing destructive land-management practices to continue, making it unlikely that either the peat bog or woodland restoration projects will succeed in the long term.

We need National Park Authorities that will speak out for conservation and in the public interest and prevent this sort of misuse of public funds. Sadly, in this case, the Cairngorms National Park Authority appears nowhere to be seen. That should provide every justification for the Minister responsible for both National Park Authorities and Nature Scot, the Green MSP Lorna Slater, to intervene.

4 Comments on “Conservation in Glen Banchor? Peatbog and woodland restoration (2).”