Having highlighted the issue of forest fences being covered in plastic to prevent bird collisions a year ago (see here), it is very good to see that the Cairngorms Capercaillie Project has been doing more work with the Seafield estate to remove the orange netting. Unfortunately, rather than removing the fences completely, they have been using volunteer time to replace the plastic with wooden markers. This post takes a further look (see here) at the role that deer fencing has been playing in the decline of the capercaillie, from 20,000 in the 1970s to 542 now (the latest figure according to the Capercaillie Project).

Why deer fences are a problem for capercaillie

Capercaillie feature very prominently in the politics of the Cairngorms National Park. The Scottish Government has committed to save the capercaillie and significant sums of public money have been thrown at trying to achieve this over the last twenty years. The lack of success has triggered controversial debates about the role of outdoor recreation and predators in the decline of the species. I will consider in further posts how the Cairngorms National Park Authority has responded to those two debates, following a paper it considered in June (see here), and what I consider the much more important issue, the lack of suitable habitat. The key point to note here, however, is that while the evidence for the impacts that outdoor recreation and predators have on capercaillie survival is mixed, the evidence for the impact of deer fences is very clear. They kill, not just capercaillie but other birds and in large numbers.

Research from the 1990s, cited in Adam Watson and Robert Moss’ excellent book “Grouse” estimated that 20,000 capercaillie a year died in Norway through flying into forest fences and that fences were one of the main causes of capercaillie mortality in Scotland. Hence the plastic netting. Further research by Baines and Andrew (see here) then showed that capercaillie collided with deer fences in the areas they studied at a rate of 0.9 collisions per kilometre per year but that marking reduced capercaillie collisions by 64% (more than for other birds). That, however, still means a very large number of capercaillie are dying through collisions with fences each year.

Scavengers and predators are remarkably efficient at removing evidence of kills and the wind does the rest, whatever the cause of death. It is likely therefore that the numbers of death by collision that are recorded are a considerable underestimate:

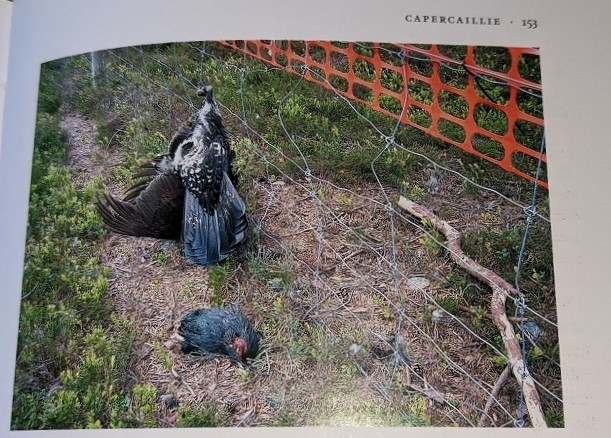

There is a great photo in “Grouse” (Fig 88 on page 152) of a garotted male capercaillie entangled in the lower section of a deer fence below orange plastic marker netting which illustrates the problem:

It is well known that capercaillie avoid dense forest plantations, partly because they cannot fly through narrow spaces between trees. Leaving the lower half of fences unmarked, therefore, or using widely spaced batons will create what looks like gaps to a capercaillie, particularly if travelling at speed. As the caption to the photo remarks:

“it seems like the capercaillie tried to fly under it [the netting] as if under a branch. Marking should make the entire fence look like an obstacle to flight”.

There have been very few fences marked in the way Adam Watson and Robert Moss advised, partly because of cost but also because the more the marking, whether wood or plastic, the more the fence catches the wind and the more likely it is to blow over.

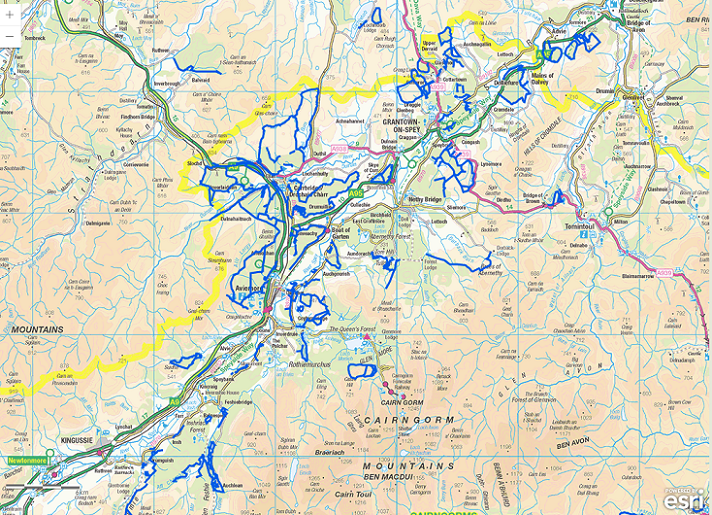

The final element in understanding why deer fencing has been such a disaster for capercaillie lies in their movements. In “Grouse” further research is cited which shows while capercaillie cocks don’t tend to travel far from leks, hens disperse on average about 12km as they reach adulthood. This means that to stop the annual decimation of capercaillie by fences, there need to large fence free areas around leks. On the northern part of Speyside, where the greatest concentration of capercaillie are still found, that means everywhere.

Fences, the Capercaillie Project and the Cairngorms National Park Authority

The most important piece of work that the Capercaillie Project has done in my view is to map the deer fencing in the Cairngorms and around Inverness (see here). They clearly appreciate the problem. Choose a wood where you have heard there might be capercaillie, draw a line to another wood 12k away and then count how many fences the hen capercaillie have to get past!

There are two challenges to fence removal, most importantly the number of red deer. In the absence of any effective action by NatureScot or the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) to bring down deer numbers on estates managed primarily for sporting purposes, fences are required to save trees – even around fragments of Caledonian Pine forest. This may save the forest but spells death to one of its finest inhabitants.

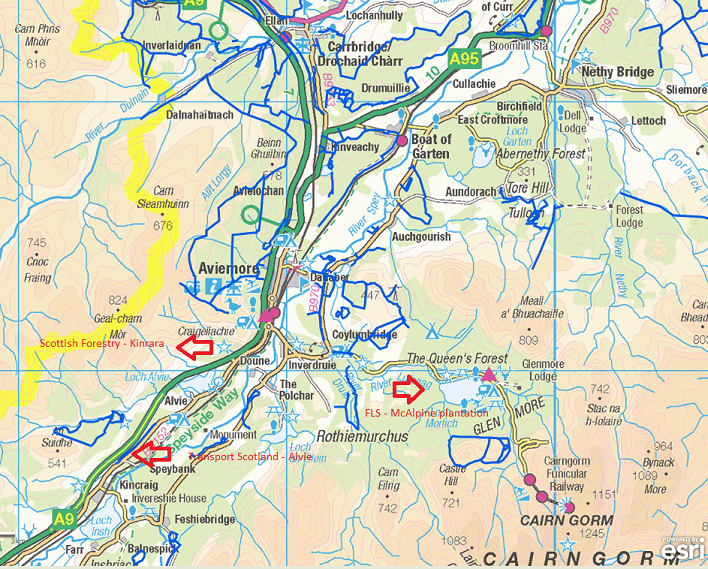

The Seafield Estate (top photo and below) provides a good example of the problem: deer sweep down from the higher parts of the Monadliath in winter to find shelter and food at Kinveachy.

The second issue is money. Estates may agree in principle to remove fencing but many of these appear not prepared to pay for the work. The Forest Grant Scheme, operated by Scottish Forestry, pays for landowners to remove or mark fences within 1km of a lek, not nearly far enough. At their Board Meeting in June the CNPA agreed to lobby Scottish Forestry with NatureScot so that when the current scheme is next reviewed, in 2024, funding is made available to remove or mark fences where-ever capercaillie might fly into them. The CNPA Board were also told that as a short term solution, until its funding ends in July 2023, “The Cairngorms Capercaillie Project continues to provide grants to mark and remove fencing over 1km from an active lek site”.

Both these actions are focussed on the right issue, even if it is still too little (fences need to be removed, not marked) and probably too late. It also rather sticks in the craw that having funded landowners to erect fences, the public is now expected to fund their removal.

It is important to note here that Seafield, featured in the photos above, is one of the few estates to contribute to the Capercaillie Project and invests far more than any other: £217,347 this year (compared to £11,500 from King Charles at Balmoral) (see here). There are also conservation estates like Wildland Ltd, who are not part of the Capercaillie Project, but have funded their own extensive fence removal.

The public agencies failing capercaillie

What the paper to the CNPA Board in June strangely failed to mention was that new deer fences are continuing to be erected in the heart of capercaillie country and surrounding areas which they must recolonise if they are to survive.

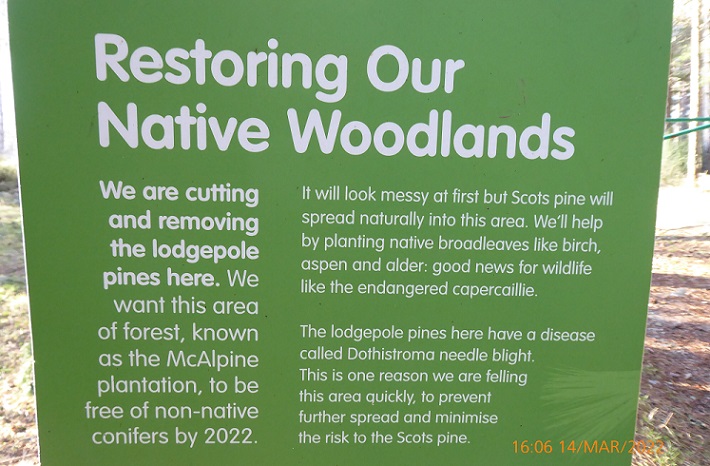

I have returned to the McAlpine Plantation by Loch Morlich at the centre of the Glenmore Forest twice since writing about it in March (see here). On the second occasion staff from the harvesting arm of Forestry and Land Scotland, who own the site, were present. They were kind enough to explain a bit more about what was going on, including that the harvesting of the lodgepole pine had been halted during the breeding season to protect capercaillie. This seemed slightly over-precautious to me because the lodgepole pine had been so densely planted that they were unlikely to provide habitat for capercaillie – something I confirmed with an expert afterwards.

If one branch of FLS was concerned enough about capercaillie at the McAlpine plantation to halt harvesting, why had another under the guise of restoring native woodland erected new deer fences?

Given the plight of capercaillie and the fact that Glen More is one of their last refuges, erecting deer fences right in the middle of the forest in what was almost a fence free zone is folly.

FLS are also members of Cairngorms Connect which claims to be the largest conservation project in the UK. While Wildland Ltd at Glen Feshie and RSPB at Abernethy have showed the way in removing deer fences, FLS appears to have moved in the opposite direction. One wonders whether FLS’ management has ever seen their ecologist Kenny Kortland’s photo of the garrotted capercaillie? But then if they can afford to ignore the local community and outsource the Glenmore campsite (see here), it is unlikely anyone else can influence them when it comes to their mis-management of Glen More.

Along the old A9, to the south of Aviemore, there is a significant length of unmarked deer fencing some of which, at least, appears to have been erected by Transport Scotland to keep deer off the new dual carriageway.

My understanding is that one of the conditions of the A9 dualling, which was put in place following representations by the CNPA, was that Transport Scotland should ensure all deer fencing should be marked. That condition unfortunately appears never to have been enforced and lengths of fence remain unmarked. The journey for any hen capercaillie that tries to disperse along the woodland corridor by the A9 has been made fraught with danger by a second government agency.

The third government agency is Scottish Forestry which has awarded over £1m to BrewDog (see here) to plant trees behind fences in an area which is also well within the dispersal range of hen capercaillie. “Capercaillie killer IPA”, has a certain punk ring to it, but to be fair BrewDog probably know little about capercaillie, follow the advice of their forestry consultants and take what’s offered by Scottish Forestry without considering the impact.

If the CNPA has objected to Scottish Forestry about their funding of BrewDog, they don’t appear to have said so publicly. If they really want to save the capercaillie, as they claim, the CNPA’s top priority has to be to stop Scottish Forestry funding any new fences now, rather than lobbying for money to be made available to remove existing fences from sometime in 2024.

Back to the plastic – a sad history of failure

A week or so ago the orange plastic netting that had been removed at Seafield was neatly rolled up by a forest track ready for collection. I am fairly confident that the estate will remove it.

There is, however, similar plastic netting on the Cawdor Estate which has been left on the ground…..

…………..since 2015! The Cairngorms Local Access Forum meeting on 12th May 2015 (see here) considered a paper on the capercaillie framework which noted that work was being done to remove both deer fencing and plastic netting that year. It also reported that:

“The top priority fence identified for removal at Cawdor Estate (in Carrbridge) due to a number of known deaths from strikes, has been taken out through CNPA funding.”

Good stuff! Since then, however, despite the abandoned fencing and netting being reported to the CNPA by local residents on several occasions nothing has been done.

Maybe that is symptomatic of the wider problem. If it is too difficult to dispose of fencing that has been taken down, what hope for the removal of the many deer fences are still in place across Speyside or for the fences that are still being erected? What hope for the capercaillie if Scotland cannot address what is the single best evidenced cause of their decline?

Following on from NatureScot’s consultation on National Parks which I consider in my last post (see here), perhaps the single most important question it failed to ask was “what powers and resources would National Parks need to reduce deer numbers to levels where deer fencing could be abolished and the rest of nature allowed to flourish?”

Nick,

A correction (typo). You wrote “Further research by Baines and Andrew (see here) then showed that capercaillie collided with deer fences in the areas they studied at a rate of 0.9 collisions per bird per year”. This should read 0.9 collisions per km per year.

Andy.

Thank you very much Andy, I have corrected, Nick

another consequence of the VED regime in Scotland

Hi, What is VED?

Good article as always. I presume you send copies of your articles that affect Brewdog to their top management. If so, they cannot claim ignorance and with some of their recent bad press they might react positively.

Sounds like a sensible idea.

It’s 2022 and the professional conservations cannot even get something this simple correct. 🙁 Also £1million to private landowners for fencing. More evidence of landowning gravy train.

Much of the Cairngorms Capercaillie Project smacks of spending a lot of money so that the public authorities like CNPA and NatureScot can be seen to be trying to do something, rather than getting to the heart of the subject – e.g. reducing red deer densities and removing deer fences.

Yes, there are other debates covering predators, but reducing red deer densities and consequently the need for deer fencing is an obvious winner, but the Scottish Government and its environmental agencies seem to be too sensitive to the opposition put up by so many ‘sporting’ estates and by the failure of FLS and Scottish Forestry to realise the error of their ways and take decisive action.

This issue is not just one of saving the capercaillie, but of real encouragement of biodiversity in these areas.

Do deer eat capercaillie?

I seem to recall more than two decades back that a RSPB camera monitoring project covering capercaillie nests (20 nests if I’m not mistaken), where it showed that 18 of the nests were predated (90%), in the main by pine marten, before a single chick escaped the eggshell; Marcström et al’s seminal work from over forty years ago on the impacts of predation on woodland grouse, along with the resulting re flourishing of the species in discrete island populations where strenuous predation management was undertaken, is still in print; must we try to reinvent the wheel even now, all and always at the expense of both the increasingly endangered capercaillie and the beleaguered public purse before the penny finally drops, preferably before the last caper does? All manner of hypotheses have been offered up as to their demise, even ‘climate change’, but the elephant in the room yet gets scant attention. Novar Estate demonstrated a few years ago how numbers could recover where efforts were made to tackle predation; when the birds were originally re-introduced from Sweden in the 1800’s, the landowners involved invoked a twenty-year predator control programme, which permitted the species to flourish, just as they did much more recently in Marcström’s case study….

…they try to tell us “It’s the weet that’s killed the population”,

but since they’ve felt the vermin’s feet, they’ve suffer’d decimation;

an’ dam a finger will they raise, tae ease their plight this day,

Preferring ‘expert’ chiels tae praise, whilst watching them decay…

The time has come to dwell upon baith ‘benefit’ and ‘cost’,

For – Some late ‘t wall be, ere comes the day, when aa’ rare things are lost..

– The choice ye mak should gaur ye think the implications clear,

And in yer conscience shall it sink – pray, mak the right choice here…

Its worth posing another question, do pine marten eat capercaillie? The answer is that they rarely catch them, just as they rarely catch red squirrel, but they probably do feed on capercaillie and other birds that get decapitated day in and day out on deer fences, that has boosted their populations which then means capercaillie nests are at higher risk of predation. I will consider these issues and the research you cite in a further post.

Interesting hypothesis, which could surely be verified (or otherwise) by use of monitoring cameras looking along tracks and trails running either side of fences you suggest are responsible for their demise.

I have to remind you though that the evidence of nest predation was brought forward decades ago now, when pine marten were less numerous than today; if they were capable of 90% predation rate on nests and each egg contained an unhatched chick or embryo, then what of today? The predation rate has been effectively sat on, unaddressed for the entire time of the birds’ decline – hardly active management.

Hard to understand why you haven’t already read Marcström’s papers by now, they highlighted the issues and solutions decades ago too.

Have you read Grouse? If so you may recall that Robert Moss and Adam Watson re-looked at the data in Marcstrom et al’s 1988 study (Journal of Applied Ecology 57) and found “it appeared that grouse breeding success was better in years with more pine martens, the opposite of what one might expect”. It would be helpful to know if there is any other evidence you are referring to so I can also consider that in the post I am planning. Thanks, Nick