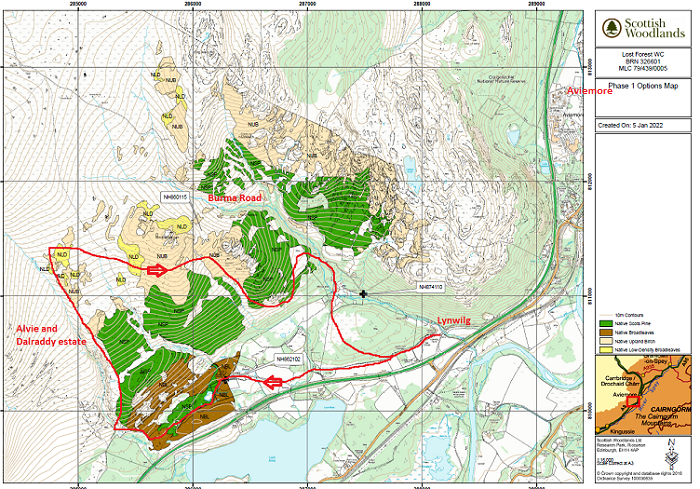

Last month it was reported that Brewdog had been awarded over £1m in grants by Scottish Forestry Scotland as part of its Lost Forest project at Kinrara. The Scottish Forestry website is very hard to use – searches for Brewdog, Kinrara and on its land based database all come up blank – and I have been unable to establish how much has been awarded and for what. The grant, however, appears to be for Phase 1 of Brewdog’s Lost Forest plans, which Scottish Forestry consulted on in February. Those plans covered the Strathspey part of the estate, all of which lies within the Cairngorms National Park boundary, and may be slightly different to the final plans Scottish Forestry has agreed.

Whatever the final details the grant award it is, as Dave Morris explained in a letter to the Herald, a misuse of public funds:

Dave and I walked round the western part of the area covered by the proposed Phase 1 forestry scheme in March having previously taken a look at the land along the Burma Rd (see here). This post builds on the arguments in his Herald letter by showing what we saw on the ground. A second post will provide a more analytical critique of Scottish Woodlands’ proposals.

We started our walk at Lynwilg, near the start of the Burma Road which crosses over from Strathspey into the Dulnain, and walked along a track that runs parallel to the A9:

None of this area was included in the Phase 1 proposal map and it is unclear what BrewDog intends to do with it. If BrewDog’s aims are to store carbon, grassland can sometimes do this as well as woodland, and the area on the left of the photo might make a nice wildflower meadow, a habitat in short supply in the Cairngorms National Park.

None of this area was included in the Phase 1 proposal map and it is unclear what BrewDog intends to do with it. If BrewDog’s aims are to store carbon, grassland can sometimes do this as well as woodland, and the area on the left of the photo might make a nice wildflower meadow, a habitat in short supply in the Cairngorms National Park.

The woodland on the right of the track had been planted, consisted mainly of oak and had been coppiced in the past. The lack of any understorey, such as holly or honeysuckle, shows this woodland has been long overgrazed. It is not included within the proposed deer fence and it is unclear whether BrewDog has any plans to reduce the grazing pressure and enable it to regenerate naturally. Not so much a lost forest as a lost opportunity.

Further on the winter storms had wreaked significant damage. Old trees crashing down might not matter so much if all around them new trees were regenerating but this woodland is on its knees. It might make it more palatable if Scottish Forestry, before shedding out loads of public money, required landowners to show they were taking appropriate action to address grazing pressure across all of their land.

BrewDog’s intentions, however, for the land outwith the Lost Forest plans are unclear. An excellent article in the Guardian in March (see here) revealed:

“BrewDog also accepted the claim Kinrara could capture up to 550,000 tonnes of CO2 a year was wrong. The correct figure was up to 1m tonnes over 100 years, it said.

Early promotions for the Lost Forest suggested each can or pack of Lost Lager sold would fund a tree at Kinrara. A recent advert on BrewDog’s online store on Amazon stated “for every pack we plant a tree in the BrewDog Lost Forest”. A BrewDog tweet offering free packs of Lost Lager in January 2021, which has been taken down, included a film about the Lost Forest under the wording “we’ll plant a tree in our forest” for every pack given away.

The company denies it intended to claim a tree would be planted at Kinrara for every sale of Lost Lager; it told the Guardian that promotion was linked to an Eden Project forest it supports in Madagascar. It changed its Amazon advert last week after it was flagged by the Guardian and promised to amend the film claiming Kinrara was 50 sq km in size.

BrewDog said the vast bulk of the Lost Forest’s overall costs would be met by the company.”

If BrewDog does have plans for this area by the A9, which don’t involve forestry grants, it’s time they went public.

Above the deciduous woodland, in an area that was included in the Lost Forest grant application, is a scattering of old pine trees which have survived extensive muirburn. Set aside the problem of overgrazing, native woodland never had a chance over much of Kinrara when it was managed as a grouse moor. The most positive aspect of BrewDog’s management of Kinrara to date is that it has stopped that.

Indeed there were other signs that BrewDog has stopped managing the land for sporting purposes, a significant change for the better as far as wildlife is concerned.

Among the devastation caused by muirburn were areas where trees had been planted by the previous owners, most probably with grant assistance from Scottish Forestry. These were also certain planted to provide cover for game birds such as pheasant, not to benefit nature more generally. The plastic tree tubes appear a later addition but probably precede BrewDog’s purchase of the estate. If, however, BrewDog really cares about the natural environment at Kinrara they should now be removing all this plastic. Plastic is oil derived, not planet punk.

As with many other sporting estates in Strathspey, we passed pools which had been excavated to provide opportunities to shoot wildfowl. With sport shooting apparently abandoned, these could now be left to develop into wilder wetland habitats. It is likely that, if left alone, much of the flat area around would develop into bog, the most effective medium term of extracting carbon from the atmosphere which is what BrewDog claims it wants to do. But instead this flat area has been included in the Lost Forest’s Phase I proposals and is likely to be planted with a mixture of Scots Pine and broadleaves.

Above, the devastation is shocking. Normally, crags provide a refuge for trees but not so here. The isolated birch, which have got away despite grazing pressure, suggest this crag might have been covered with trees if it were not for the muirburn.

BrewDog, not shy when it comes to publicity, could have made far more about having put a stop to this scorched earth policy but so far appear to have said nothing. Perhaps they are more traditional than they appear and don’t want to ruffle the feathers of their neighbouring landowners?

As we approached the neighbouring estate, Dalraddy and Alvie, over moorland that is to be planted, a stock fence ran up the hill. Under the Lost Forest proposals, it appears this fence will be replaced by a deer fence paid for by Scottish Forestry grant.

No sooner had we started up the fence than we came across a juniper sprouting out the heather, an early indication that there are plenty of native trees waiting to emerge from the former grouse moor if only they were given the chance.

Although the foreground looks tree-less from a distance, if you got down on your knees for a much closer look, you would find seedlings among the heather and bracken.

Slightly higher up the Allt Chriochaidh, which runs between the Alvie and Kinrara estates, where it became a steep sided gorge inaccessible to deer or sheep there was a mini-forest, with both native and non-native trees. This provided another seed source and, as soon as we started looking among the heather, we found plenty of young pine.

This area was earmarked on the indicative Scottish Woodlands map for planting Scots Pine. There was no justification for this as the trees are already there and with muirburn terminated half the problem has been solved. The problem is and was that as soon as the pine seedlings emerge from the heather they are browsed to destruction. But why just apply for a grant to put in a fence when you can also received lots of money to plant trees?

At least BrewDog does not appear to want to plant this area of bog, which appears as a tree-free strip in the Scottish Woodlands map. But it is proposing to plant the land on either side by turning over the peaty soils and planting trees on the resulting mounds, 1,600 per hectare is what was proposed here. That will destroy soils and release carbon into the atmosphere.

If instead BrewDog decided to manage this land like Glen Feshie and bring deer numbers down to two per square kilometre, much of the Lost Forest Phase I area could be covered with trees in 20 years without any further human intervention.

Ironically, around the time Scottish Forestry agreed to shell out c£1m to BrewDog for fences and planting, they announced they were providing grant to Wildland Ltd, who manage Glen Feshie, to promote woodland expansion by natural regeneration (see here). What is the justification for the very different approach at Kinrara? And why does BrewDog not learn from Wildland Ltd?

I could show a lot more photos but they would illustrate the same simple points. The extent of the destruction caused by muirburn has been extensive but now that has stopped the best way BrewDog could lock up carbon without releasing more into the atmosphere is to reduce grazing pressure and let nature get on with the job. As Dave Morris said in his letter, instead of forestry consultants based in Edinburgh, BrewDog should be employing deer stalkers who live locally.

The only planting that in my view might be justified on the Strathspey side of Kinrara are “missing” species but those are not the focus of the Lost Forest Plan and, because of all the overgrazing and muirburn, no-one can know what has survived and what has not until the land has been given an opportunity to regenerate.

What needs to happen

BrewDog has to its credit stopped muirburn at Kinrara but risks undermining the benefits that will bring with its Lost Forest scheme, which will do little to reduce deer numbers and is dependent on deer fencing and planting paid for by the public.

Sadly the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) has failed to address the issues of muirburn, overgrazing and inappropriate planting behind deer fences since its creation 20 years ago. While it has now adopted a policy presumption in favour of the natural regeneration of native woodland, the credibility of that policy will be undermined if the Lost Forest proposals go ahead.

The underlying explanation for both of these failures is money. It is Scottish Forestry’s grant schemes which more than anything else determines what happens on the ground and, until these are reformed, even supposedly alternative landowners like BrewDog will chase the money. Meantime the public – as I will show in my next post on Kinrara – are almost powerless to influence what happens on the ground, whatever the Scottish Government and the CNPA’s ostensible policy objectives.

Postscript

An article in the Herald on 2nd July revealed that species rich grassland has been declining at a rate of 2% a year in the Cairngorms National Park since 2006/07. A good reason, one might have thought, for BrewDog, to restore wildflower meadows at Kinrara as well as plant trees.

It’s a pretty toxic combination – Scottish Forestry setting up the wrong financial drivers, CNPA pretending to care, but ‘asleep at the wheel’ and a large company which owns the land with a dangerously superficial PR policy. Where is the direction from the Minister Lorna Slaterand her Cabinet Secys Mairi McAllanand Michael Mathieson – I suspect lost in the overly complex Scottish Government ministerial structure.

Until companies are prevented from claiming tree planting on their estates as part of their net zero plans, this type of problem will be replicated all over Scotland. There is too much rhetoric about who owns our land and not nearly enough about what these owners are doing with their land. There is a very high risk that this rhetoric will negatively interfere with the Scottish Government’s Land Reform ideas.

Look into those companies that are selling Scottish lord titles we see on Internet adds they also get a tree planted on their we bit of land. I believe its all connect to brew dog and the snp in Holyrood