The disappearance of two further tagged hen harriers within the Cairngorms National Park was entirely predictable. Its almost certainly blown apart the commendable target the Cairngorms National Park Authority set in its National Park Partnership Plan “To eliminate raptor persecution”. That should not be a surprise. The 2017-22 Plan failed to tackle the underlying cause of raptor and other wildlife persecution, the farming of grouse to be shot. As long as the primary purpose of land management in much of the National Park is maximisation of grouse numbers, predators will continue to be exterminated by whatever means possible. Other species, such as the mountain hare, will also be caught up in the slaughter simply because they might transmit ticks to grouse or provide food for predators.

Instead of addressing intensive grouse moor management, the CNPA is currently focussed on trying to detect the crimes which flow inexorably from it. They are supporting improved raptor tagging technology, which might help pinpoint the exact place a raptor died, and the recruitment of special police constables. The idea, presumably, is to deter the crime. A crime that is required if grouse moors are to provide sufficient bags to satisfy the shooting fraternity’s demand for grouse. The measures are far to weak to have any chance of success. How the special constables will catch culprits is not explained. Establishing the point of raptor death, does not prove who did it. As Raptor Persecution Scotland has repeatedly demonstrated, even when there is good evidence for the culprit, its remarkably hard to secure a conviction.

What would happen however if we turned this around? Instead of just tagging raptors, why not also tag gamekeepers? The idea was suggested, briefly, by a commentator on Raptor Persecution UK’s posts on the disappearances of Stelmaria and Margot. It should get people thinking. Instead of having to work out which estate staff were in the vicinity when a raptor disappears, tags would show who was where when. This would make it much easier to link a raptor’s disappearance with the likely culprit. Even if this was not sufficient for the criminal courts, in civil terms it should be sufficient to remove an estate’s license to shoot grouse – a massive deterrent. The concept, in principle, seems a good one and could give the current campaign for grouse moor licensing some teeth

The challenge would be enforcement. To ensure individuals carrying guns, say, were also carrying tags would be labour intensive and challenging. Enforcement of a requirement that all estate vehicles driving on estate land should track their position using GPS would be much much easier. This would not require special constables to search or confront anyone. All they would need to do is photograph a vehicle from afar and then check from an online tracking system whether the vehicle had its GPS device switched on. The Special Constables could then match these records and take action against any vehicles that had their GPS switched off. Hillwalkers and other visitors could greatly assist the enforcement process by uploading photos of vehicles, just as many already do with wildlife, which would then be checked by the special constables.

Such a measure would make raptor persecution far more difficult. A prime reason estate tracks have been constructed all over the hills is to make intensive grouse moor management easier. Estate staff drive around checking traps, putting out medicated grit and keeping a look out for predators. One person can do what five previously did and raptor persecution has as a consequence become more efficient. That’s why they should be called persecution tracks. Mapping raptor and other wildlife decline against track proliferation would make a nice student project to support this contention. Keepers could of course still walk five miles across the moor to destroy a hen harrier’s nest. That job though would be much harder and more raptors would escape.

A second stage would require anyone carrying a gun or a trap to carry a tracking device. Enforcement could be assisted if estates were required to report online where traps were located. Again, if hillwalkers and other visitors were able to uploads photos of traps – I have dozens – as they do for wildlife, those records could easily be checked against those of the estate by special constables. Tracking movements would make persecution harder. Where estates had failed to use the GPS system to report traps, again they would lose their licence.

The first proposal, to track the movements of all estate vehicles, could be fully implemented within the National Park in 18 months given the will. Conservation minded owners, such as the National Trust for Scotland or Cairngorms Connect, could pilot the use of GPS monitoring devices over the next few months. Existing data bases, such as the RSPB’s one for recording raptors, could be adapted to record vehicle movements. The CNPA could meantime commence discussions with the East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership, its preferred mechanism for improving grouse moor management, and get them signed up to pilot the system from April. The CNPA could then consult on the introduction of byelaws to require estate vehicles to carry GPS devices from April 2020. Under the National Parks (Scotland) Act Schedule 2 Section 8 (2) b the Cairngorms National Park Authority can make byelaws “to regulate the use of vehicles (other than the use of vehicles on a road within the meaning of the Roads (Scotland) Act 1984 (c.50))”.

Having led the way, the CNPA’s tracking system could then be adopted countrywide as part of grouse moor licensing. It sounds, and is, very simple. Could it happen?

What’s preventing the development of proposals to control grouse moor management?

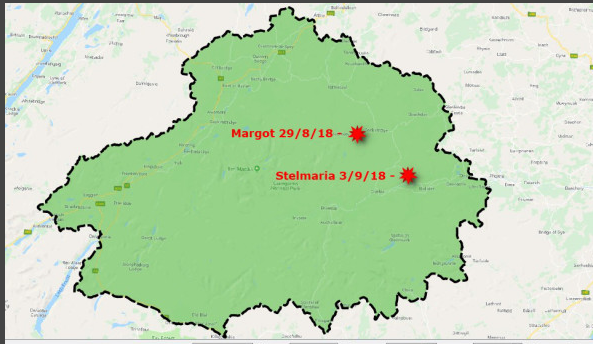

Detective work from Raptor Persecution Scotland has shown that the first hen harrier to disappear, Margot, did so near the boundary of three estates, Glenavon, Allargue and Delnadamph (see here), while the second, Stelmaria, did on on near the boundary of the Dinnet and Invercauld estates (see here). Two of these estates, Invercauld and Glenavon, are part of the East Cairngorms moorland partnership which also includes the Mar Lodge, Mar, Balmoral and Glen Livet. At least one other, Allargue, which owns the Lecht Ski area, is part of the Wildlife Estates Initiative launched by the current Minister for the Environment, Roseanna Cunningham, in 2010.

That means that if these two raptors were unlawfully killed, three out of the five likely estates responsible are in theory signed up to protect wildlife. Embarrassing for the National Park. If you discount those three estates, that would mean Hen Harrier Margot disappeared on Delnadamph. That estate is owned by Prince Charles, even more embarrassing not just for the Park but for the Scottish Government. We can be confident there is unlikely to be any effective criminal investigation in this case.

The Royal Family and Balmorality lie at the root of the grouse moor problem. Queen Victoria – or should one say Albert? – gave legitimacy to the whole concept of the Highland Sporting Estate. This put shooting before everything else, and Victoria’s descendants have continued in that tradition, modernising it as they went along. Raptor Persecution Scotland provides links which show the Queen’s Trustees bought Delnadamph in 1978 for Prince Charles because Balmoral “didn’t have adequate grouse shooting”. Grouse numbers again.

While as part of the CNPA’s excellent initiative to improve transparency, Balmoral has provided an estate management statement, Delnadamph hasn’t. If Prince Charles fails to do so, why would other estates? Balmoral’s estate management statement (see here), has a section on how it will deliver the National Park Plan. This says nothing about eliminating raptor persecution or what it is doing to protect other wildlife. So, why aren’t the Royal Family setting an example? Just how many hen harriers are nesting on the Royal estates? Why the silence on raptors while Prince Charles goes overboard in the latest issue of Country Life on how he lets red squirrels run around his residence at Birkhall (see here)? What’s unsaid by the Royal Family is as important as what is said.

If you want to understand why grouse moors continue to predominate in the eastern part of the National Park or why the NTS at Mar Lodge has been so slow to reduce deer numbers, look no further than the Royal Estates. Balmorality helps explain why the CNPA has adopted a voluntary approach to estate management. They don’t dare challenge the royals. It also illustrates why the voluntary approach will never work. The CNPA needs to be brave. Insist the Royal Estates sign up fully for National Park objectives as they were forced to do with our access legislation (the first proposals before the Scottish Parliament exempted Balmoral).

Of the other four estates potentially involved in the disappearance of these two hen harriers, three have provided estate management statements. (Glenavon hasn’t, despite being part of the East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership).

The statement from Dinnet abdicates any responsibility: Sporting is entirely let out for fishing (Loch Kinord and the Dee), shooting (grouse moor and low ground) and stalking.

The statements from Invercauld (see here) and Allargue (see here), are silent on how they will help stop wildlife persecution. That from Invercauld gives little indication of its approach to grouse moor management and numbers. That for Allargue makes clear that intensive grouse moor management is integral to what they do:

“Grouse management and shooting – 65%. This involves heather burning, predator control, tick and

disease control, careful grazing.

Red and Roe deer management – 5%. As for grouse, but numbers controlled by stalking and presently limited by culling for tick reduction and plantation felling programme.”

As an aside, the obsession with ticks transmitting disease to grouse in this case has the happy consequence of reducing deer numbers. Sadly it appears that any regeneration of the vegetation that results from this is then burned to preserve grouse habitat.

What needs to happen

It is likely that all these estates will resist anything which challenges their right to manage the land as they wish and, more specifically, their right to produce as many grouse as modern farming techniques allow. Even where not involved in raptor persecution, its in the interests of grouse moor owners that other estates are allowed to continue the killing spree. Hence the general opposition to grouse moor licensing and the reluctance of estates to publish transparent management plans.

While I support grouse moor licensing, unless this includes effective measures to prevent wildlife persecution, such as tracking keepers, and changes management away from the production of large shooting bags, it is unlikely to work. The CNPA could play a crucial role in changing this and developing new models which could then be replicated across Scotland. That, however, would require ALL estates to operate transparently and for the CNPA to start a public debate on land-use. Their Board needs to be inspired by the example of access rights, ignore the establishment, listen to the public and start taking effective action.

Some interesting thoughts on how to prevent raptor deaths on grouse moors. It’s clear that the three recent hen harrier ‘disappearances’ within CNPA land is not the result of deaths by natural causes, otherwise the trackers would keep transmitting and the dead birds would have been found – as has happened in various other cases. Tagging gamekeepers won’t work – even tagging convicted criminals has run into problems! GPS trackers on estate vehicles is an interesting idea and should at least be trialled.

I agree there is much more that CNPA could do to insist on full co-operation by the grouse moor estates and ensure that they have comprehensive management policies, open to public scrutiny. The Scottish Government must take action on grouse moor licencing, however I agree that licencing without appropriate controls will just not work. One idea that needs to be followed up is finding ways of taking significant financial sanctions against any estate owner whose staff are found guilty of wildlife crime. Such sanctions might stop the ‘Nelson’s eye’ approach which seems to be adopted by at least some estate owners.