The Werritty report (see here), which was published a week before Xmas, is not disappointing, as some have claimed, its what everyone should have expected.

Both the remit for the review and the membership of the review group were wrong from the outset. The question which the Scottish Government should have asked is not whether grouse moors can be managed better, its whether they should exist: whether, for example, grouse moors are compatible with the statutory objectives of our National Parks to conserve nature and make sustainable use of resources. Then, after the Scottish Government had appointed two strong advocates of grouse shooting to the so-called independent review group, it was inevitable that over two and a half years later all the Review Group would recommend was tinkering to the current system.

Its worth taking a critical look at the report, however, to understand better what is going wrong with conservation in Scotland at present and I will do so over a couple of posts.

Grouse moors and conservation in our National Parks

There are just three references to National Parks in the report, one in the body of the text stating that among the bodies responding to a questionnaire was a National Park and two in the references. That’s it! While there is a whole section on regulation, there’s not a mention of the powers that our National Parks have to create byelaws regulating how land is used for conservation purposes. These could, for example, be used to ban the three damaging practices associated with grouse moor management which – as well as raptor persecution – are considered in the report, namely muirburn, use of medicated grit and killing of mountain hares. There is a very very strong argument that NONE of these practices are compatible with the statutory duty of National Parks to put conservation first.

There is no discussion in the report of the relationship between the designations created by the EU Habitats Directive, which are now supposed to be the primary means for protecting habitats and species, and the practices associated with intensive grouse moor management such as raptor persecution, muirburn, killing of mountain hares and use of medicated grit. There is not a single reference to Special Areas of Conservation (designed to protect habitats), although Special Protection Areas (designed to protect birds) are included in the list of acronyms at the end. Since there is no reference to them in the body of the text, it appears that Review Group decided to edit out any reference to SPAs from the body of the main report.

The Report uses the term “designated sites” once and and there is one reference to Sites of Special Scientific Interest, which are supposed to form the building blocks of our conservation system:

“There could also be a greater willingness to consider using existing legal measures. Examples include reviewing whether changing ecological conditions (such as the decline in nesting wader populations) mean that more grouse moors now meet the scientific tests to qualify for a statutory conservation designation, e.g.Sites of Special Scientific Interest, that may both impose some further regulation and open the opportunity for financial support for management activities.”

Again, that’s it! One suspects the only reason that SSSI have been mentioned is because they might “open the opportunity for financial support” to landowners.

Scottish Natural Heritage has powers under our designation system to control what land management activities take place on grouse moors that have been designated as protected areas by specifying Operations that Require Consent (ORCs): these sometimes include muirburn and there is no reason why they shouldn’t be used to control use of medicated grit and culling of hares. SNH also have a statutory duty to monitor the condition of these designated sites and powers to intervene where sites are in an unfavourable condition. Despite this extensive statutory framework nowhere in the report is there ANY analysis of the condition of grouse moors or how effectively SNH are using their powers – although the evidence that they are failing to do so is everywhere, see here and here for example.

Instead, the Report entirely ignores habitats and focusses on raptors populations in its first and main recommendation:

“We unanimously recommend that a licensing scheme be introduced for the shooting of grouse if, within five years from the Scottish Government publishing this report, there is no marked improvement in the ecological sustainability of grouse moor management, as evidenced by the

populations of breeding Golden Eagles, Hen Harriers and Peregrines on or within the vicinity of grouse moors being in favourable condition”

Readers are then referred to the glossary which defines “favourable conservation status” as follows:

“The statutory nature conservation agency, SNH, advises JNCC and the UK and Scottish governments on the condition assessments, based on ‘condition objectives’ set for individual species and sites (SPAs, SSSIs), and EC Birds Directive Article 12 and EC Habitat Article 17 assessments. On collating returns from a variety of sources, the conservation status of the species being considered can be reported as:

– Good: Favourable

– Unknown

– Poor: Unfavourable-inadequate

– Bad: Unfavourable-bad

– Not applicable/not reported

with the category ‘inadequate’ referring to the available data.

In the present context, emphasis will be placed specifically on the local conservation status of raptors (especially, Golden Eagles, Peregrines and Hen Harriers) on and around grouse moors.”

What this appears to besaying is that whether the conservation status of raptors has improved will be determined in part by using the same criteria as for protected areas and using information collected for them. So, having ignored what’s actually going on in protected areas, which includes SPAs designated to protect raptors, the main recommendation is based entirely on protected areas methodologies.

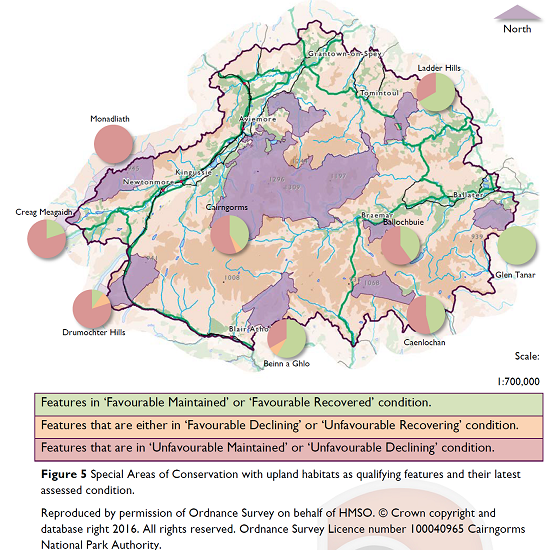

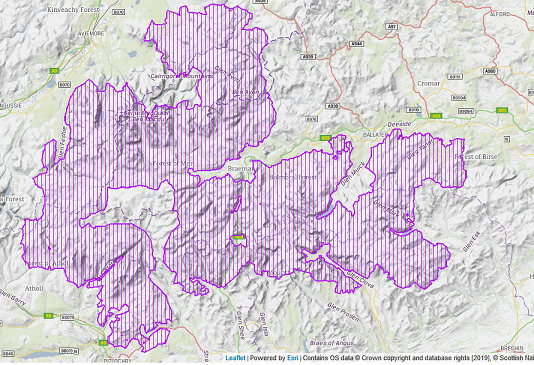

Had all the Review Group looked at SNH’s latest condition reports for the Cairngorms Special Protection Area, which is partly designated for its golden eagles, they might have realised there are serious problems with their recommendation:

For the status of the golden eagle in the Cairngorms SPA has consistently been judged by SNH as being favourable since 2005 (see here) – the Review Group’s recommendation already achieved! This is despite the Cairngorms National Park and the surrounding grouse moors being one of worst places in Scotland for golden eagle persecution (see here for latest map from Raptor Persecution Scotland).

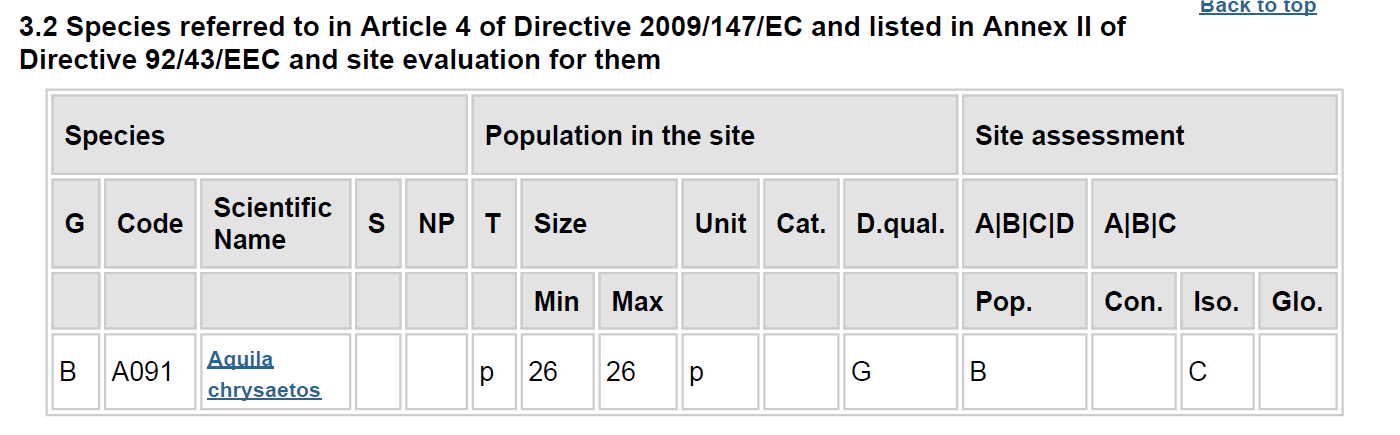

Its worth considering SNH’s evaluation of the status of the golden eagle in the Cairngorms SPA a little further. In 2015 they provided the following report to the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the EU:

Two crucial columns in the report, Cat = Abundance Category and Con = Conservation Status are blank. So while announcing at home that the conservation status of the eagle in the Caingorms SPA was favourable, it appears SNH avoided making any judgement to the EU. Why?

The broad picture is that there is food in the Cairngorms SPA for significantly more than 26 pairs of golden eagles, as reported to the EU, but that while nesting successfully on the west side of the SPA (the Cairngorms Connect and Mar Lodge Estate areas) as soon as young eagles (or hen harriers etc) move out to look for territories onto moors managed for grouse shooting they disappear. (This has been extensively documented by Raptor Persecution Scotland).

This conflicts with the stated conservation objectives of the Cairngorms SPA which include:

- “Distribution of the species within site”

- “No significant disturbance of the species”

Despite this, SNH has judged the conservation status of the golden eagle in the Cairngorms SPA to be favourable.

This demonstrates first that there is something very wrong with our EU based conservation system and second that the main recommendation in the Werritty report appears completely meaningless since the criteria they have chosen to judge any improvement in grouse moor management has already, in the case of one persecuted raptor species, been met for a large junk of Scotland.

Planning and grouse moors

Our Planning System also has a key role in ensuring conservation objectives are met but the Report’s approach to this is equally shallow and restricted:

“At its first meeting the Group reviewed its terms of reference and explored whether or not to expand them to include the draining of grouse moors and the expansion of tracks across grouse moors.”

The Group decided not to which effectively precluded any consideration of how planning powers might be better used to control what happens on grouse moors. Hill roads, of course, provide the infrastructure which enables and facilitates estates to carry out the three specific issues the Report did consider, muirburn, medicated grit and hunting of hares.

The amount of land used for grouse shooting and its importance

While ducking the issue of the conservation status of grouse moors, the report nevertheless states that heather dominated moorland is an EU priority habitat:

“Uplands cover around two thirds of Scotland’s land area, with almost 15% of the land area being heather-dominated moorland – the ideal habitat for grouse and a EU priority habitat of which 75% is found in the UK. The Scottish Moorland Group estimates that less than 7% of Scotland’s land area has some component of grouse moor management”.

This short paragraph contains one false and one highly dubious claim. First Steve Carver, a mapping expert who is best known for his work mapping wild land in Scotland, has shown that the claim that 75% of heather dominated moorland in the EU is found in the UK is a myth (see here). Second, the 7% figure provided by the Scottish Moorland Group, an organisation representing landowners, of the amount of land with some component of grouse moor management is only half that quoted by Dr Helen Armstrong in her report for the Revive coalition (see here):

“Around 19% of Scotland’s land area is used for both walked-up and driven grouse shooting. Driven grouse shooting takes place, or has recently taken place, on land holdings covering around 13% of Scotland’s land area.”

So why did the report on the one hand exaggerate the extent of Scotland’s heather moorland in a European context but on the other try minimise the area of moorland managed for grouse shooting and fail to say anything about whether it was in a good condition or not?

Our designation system and the way SNH oversees it plays into the hand of landowners. We have ended up with intensively managed heather moorland, a very degraded habitat, being protected by the EU because of its alleged rarity. This justifies and entrenches destructive grouse moor management techniques such as muirburn, which degrades the habitat while releasing carbon into the atmosphere. At the same time the lack of any effective enforcement means means landowners have been able to intensify grouse moor management further even on protected sites through new techniques like feeding grouse medicated grit..

Mountain Hares

The EC Habitats Directive is again referred to in the section on mountain hares:

“The Mountain Hare is on the Scottish Biodiversity List with the UK Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) report to the EU for 2013-18 reporting Mountain Hares as being in an “unfavourable-inadequate” conservation status.”

Reason to act one might think, particularly because of the one sentence in the report which helps take the debate on grouse moors forward:

“There is no substantive evidence to support the population control of Mountain Hares as part of tick and/or Louping Ill virus control to benefit Red Grouse.”

Its for their alleged role in passing on trick and the Louping Ill virus that an average of 26,000 mountain hares have been killed each year on grouse moors. So why not stop now and protect them the whole year rather than half a year as at present?

The Report fails to consider this option, even for National Parks which have a statutory conservation duty, but instead recommends “increased regulation”: this involves land managers counting the number of hares they see, reporting the numbers they kill, more research on how the killing of hares is affecting the total population and a new code of practice etc. The purpose of this is unclear – the assumption in the report appears to be that landowners should have the right to cull mountain hare if that is what they want to do even if it makes no sense – and would be extremely costly to implement. It would be far cheaper and more effectively simply to offer full protection to mountain hares and that in turn would provide plenty of food for the predators the review group says it wants to see once again on grouse moors.

Where next?

Its now 21 months since Nicola Sturgeon condemned mass culls of mountain hares (see here) and yet we are no further forward. That rather sums up not just the Werritty Report but the state of nature in our National Parks – with a few honourable exceptions – and in Scotland as a whole. My next post will consider one of the main reasons for this – the power of the landowners – which is evident throughout the Werrity Report.

Have you seen this article Nick – https://standpointmag.co.uk/issues/december-2019-january-2020/carbon-carnage-the-real-cost-of-the-grouse-shooting-industry/

I had thanks Mike but would recommend all readers take a look – I hope to write more about the carbon cost of grouse moors in due course

There are many shortcomings in the Werrity report and, indeed, in its remit in the first instance. The greatest of those is the complete and utter failure of the report to place the short term effects and long term consequences of current practice in the context of the entire range of areas afforded, notionally at least, some form of environmental protection. Most painfully absent is any meaningful reference to our National Parks – and in this context, The Cairngorms National Park in particular.

It might reasonably have been hoped that the very special aims and objectives of our National Parks might have been recognised, explored and a case developed for a specifically very different approach to be taken within them. One, for instance, where muirburn and medicated grit were banned totally, alongside a complete five year ban on killing mountain hares, followed by strictly licensed and limited numbers thereafter.

Such an approach by Werrity – or something at least somewhere near – would have given the Scottish Government and their Parks the ammunition to try the bold experiment and to compare the results over time. I might go so far as to suggest that the comparison would condemn the current practices in every respect.

Sadly, that didn’t happen, and all we can hope is that the Cairngorms National Park Authority, working with Cairngorms Connect and cajoling and encouraging the East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership can be bold and push the boundaries.

In the meantime, at least in National Parks, it’s high time that vehicular hill tracks above 400m in altitude, regardless of stated ‘use’ and regardless of whether new or being ‘improved’, required planning permission, with a presumption against, unless stringent design, mitigation and / or replacement guidelines are met.