“Forest” = “a large area covered with trees and plants/undergrowth”

Following my posts about BrewDog’s “Lost Forest” at Kinrara in February (see here) and (here), I was sent further photos showing work that had taken place in October and November last year to restore peatland and prepare the ground for tree planting. It looked terrible (see above) but I wanted to see for myself. I finally managed to visit three weeks ago. This post will compare what I saw with the vision set out in Scottish Forestry’s contract with BrewDog which stated that:

“The Lost Forest landscape scale project aims to sequester carbon and to improve the ecological value of the property over a period of years through creation of a series of new woodlands and peatland restoration”.

Background

In February 2022, after several visits to the estate, I submitted an objection (available here) to BrewDog’s proposals to plant trees on the eastern side of Kinrara, the area that is within the Cairngorms National Park. Based on the extensive natural regeneration of trees that was beginning to emerge across the site, it was obvious that all BrewDog needed to do to re-establish the Lost Forest was to control deer. Nature would do the rest.

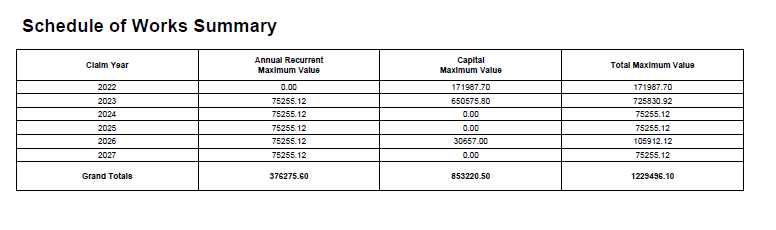

Scottish Forestry ignored the representations made by myself and others about this and in June 2022 awarded BrewDog up to £1,229,496.10 over 6 years to erect a forest fence and dig up a large part of Kinrara to plant trees. The driver behind this is that Scottish Forestry are under pressure to meet their tree planting targets in order that the Scottish Government can claim they are doing something to offset the impacts of climate change (see here for recent statement to this effect).

Work to erect a deer fence and “prepare” the ground for planting started last autumn and the trees must have been planted this spring. During this same period peat-bog restoration was being undertaken on Kinrara, also funded by the public, and while most of that work lies outwith the new forest fence some lies within it and will be considered here.

The map shows my approximate route and the approximate position of the areas illustrated in the photos below. I walked up the Burma Rd (brown line from point 1-5) then walked back done across the hillside (the thick black lines and areas 6-8)).

Some starter questions for BrewDog’s carbon accounting

The former wooden gates (point 1 on map), a sustainable forest produce, have been replaced by galvanized steel gates, again at public expense. The justification for the change is unclear but steel fabrication is one of the main sources of carbon emissions worldwide. This raises the question as to whether BrewDog has taken into account ALL the carbon emitted by the Phase I work to plant a “Lost Forest” when making its claims to be taking carbon out of the world’s increasingly hot “air”? (The steel in gates and fencing, machinery, transport etc).

The former wooden gates (point 1 on map), a sustainable forest produce, have been replaced by galvanized steel gates, again at public expense. The justification for the change is unclear but steel fabrication is one of the main sources of carbon emissions worldwide. This raises the question as to whether BrewDog has taken into account ALL the carbon emitted by the Phase I work to plant a “Lost Forest” when making its claims to be taking carbon out of the world’s increasingly hot “air”? (The steel in gates and fencing, machinery, transport etc).

Not to mention the other pollution the planting work has released into the atmosphere in what is supposed to be a National Park:

The stupidity of paying to plant trees among natural regeneration

A few hundred metres up from the car park (point 2) there is an established native woodland plantation on the right. Just above it there is now an area of dense natural regeneration on ground which was formerly heavily grazed:

This natural regeneration is now rapidly spreading up the hill across an area, as shown on the map above, where Scottish Forestry agreed to pay BrewDog to plant Scots Pine.

Scottish Forestry will now pay grants to promote natural regeneration. The contract with BrewDog states this will be paid at £300 a hectare and is supposed to be for NEW natural regeneration. Perhaps that is why it wasn’t claimed here? Instead, the information in the contract suggests Scottish Forestry have agreed to pay BrewDog £1840 a hectare to plant Scots Pine.

If successful, the planted Scots Pine will eventually shade out and kill off all the naturally regenerating birch. Meantime, as the map shows, on other parts of the site Scottish Forestry has paid BrewDog to plant birch. This is bonkers and suggests that the Scottish Government’s oft repeated mantra that the right tree should be planted in the right place is meaningless guff.

While replacing birch with pine does nothing to help expand woodland cover in Scotland it does help Scottish Forestry meet the Scottish Government’s planting targets.

Areas of scraped ground were visible among the regenerating birch raising the question of how many had been dug up or had their roots destroyed during the “ground preparation” process? From a distance it was hard to see any pine on the scraped ground which made me wonder if most of the planting was still to happen.

The answer came a little further up the hill, above the ugly and unrestored quarry which BrewDog Chief Executive must have passed when he drove up this road in July (see here)……………..

An ATV track headed up the hillside (point 3). It was immediately obvious why I had spotted so few planted pine below:

An ATV track headed up the hillside (point 3). It was immediately obvious why I had spotted so few planted pine below:

Most of them were dead. Dave Morris was with me at this point and we had to look quite hard to find a single live pine tree on the “mounds” closest to the road. It appeared most had failed to survive the drought earlier this year.

The survival rate, among both pine and broadleaves, did improve as we moved up from the Burma Rd and onto less steep ground. This was probably because this ground was boggier and less well drained.

What was striking, however, was how around the dead planted trees there many examples of self-seeded trees all of which had survived. This difference may have been partly due to the naturally regenerated trees having had more time to establish root systems. The photo above, however, also shows how mounding, which is intended to promote tree growth by draining peaty soils and removing competition, can have the opposite effect and starve the tree of water. By contrast the vegetation around the naturally regenerated trees helps keep the moisture in the ground and get the tree established.

The methods being promoted and supported by Scottish Forestry through the Woodland Grant system appear in need of a radical rethink due to the changes in weather that are a consequence of global warming. The need to adapt forestry practice to climate change, however, was not even mentioned by Scottish Forestry in their news release last Thursday (see here) about the responses to their recent consultation on the Woodlands Grant Scheme.

I also came across several examples of trees that were lying on the ground with their roots exposed, some dead, some not. At first I wondered if they might have been knocked over or unrooted by an animal (there are no obvious signs of browsing). Looking at this photo, however, subsequently it appears that the soil supporting the tree had been washed away quite recently. There was no evidence of that happening around trees that had regenerated naturally. Whether drought or flood, natural regeneration appears a baetter way of establishing woodland than planting.

A little further on below the Burma Road (point 4) some larger broadleaves and Scots Pine had been planted within 25m of mature trees and an abundant seed source, again with evidence of natural regeneration all around. While it is not easy to tell what was to planted where from the map above, this area appears to have been reserved for natural regeneration. So why has it been planted?

Above point 4, where the Burma Rd bends to the South West, Scottish Forestry’s map shows several small areas of planted pine among a larger area of natural regeneration. Looking up hillside it was impossible to make any sense of the map or understand how Scottish Forestry had agreed to pay to plant some bits while leaving other bits to nature.

Tree planting versus peatland restoration

Approaching where the Burma Rd crosses through the new forest fence (point 5) there was an area of peatbog restoration which had been organised by a different consultant and a different contractor to the forestry work.

Generally the work had been done to a high standard. However, for some reason the grit stations for grouse had been left as they were. While this had created pools, the exposed peat has been oxidising away and it was difficult to understand why it had been left out of the restoration work.

Perhaps the works specification produced by Strathcaulidh, who oversee peat-bog restoration in the Monadhliath on behalf of NatureScot, was focused solely on blocking drains?

More seriously, it was not clear if it was the peatland restoration diggers or the forestry planting diggers which churned up this peat. Whichever contractor/design consultancy was responsible, the destruction points to the wider problem. Why is the Scottish Government paying to restore areas of peatland and plant trees if adjacent to the restoration work the destruction of peat continues?

I followed the inside of the new forestry fence (which will be subject of a further post) around to point 6 where there had been more peat-bog restoration work:

Generally the peat-bog restoration work within the Phase 1 Lost Forest area is far less obvious than the tree planting work. What looks good is usually also good from an ecological viewpoint.

Less than twenty metres above another digger had been scraping away peat and vegetation – I hesitate to call this mounding – on which to plant trees:

What is the rationale behind the Scottish Government using public money to cover up bare peat with vegetation on the one hand while right next door it is paying to scrape away vegetation and leave peat exposed to the atmosphere?

From an ecological and carbon perspective there is no joined up thinking. One Scottish Government funding stream pours public money into Scottish Forestry, the forest consultants (in this case Scottish Woodlands) and the planting contractors who dig up peat, another pours public money (£250m over ten years) into NatureScot, the consultants (Strathcaulaidh) and the peatland restoration contractors. Many of the workers doing such work know this is crazy but they have no say and need to earn a crust.

The rationale behind this stupidity is that of markets. The Scottish Government is trying to support the creation of carbon off-setting markets to mitigate the impact of climate change through the Peatland Code and the Woodland Code, hence all the money being invested into peat-bog restoration and planting. From an investor perspective, however, it really doesn’t matter if peat is being dug up to plant trees or trees are being pulled up to restore peat (that is part of Abrdn’s plan at Far Ralia). All that matters is the financial return which includes the money that can be made out of government grants.

Carbon emissions and off-setting – trees v peat

Peat is far more important for storing carbon than any other soil or woodland and Scottish Forestry is slowly being forced to acknowledge this. They now have a policy presumption against planting on or in deep peat, defined as peat more than 50cm deep, or ploughing where peat is more than 10cm deep.

While I had a strong suspicion that there were a significant number of “mounds”/scraped areas near the peatbog restoration where the peat was more than 50 cm thick, I hadn’t carried a probe to establish this. Whether or not the contractors tested the ground, my visit re-inforced my belief that peat depth is irrelevant.

“We stop off to climb what can only be described as a near-vertical mound, to see some of the planted trees. I had half expected a near complete forest when I’d arrived but the saplings are tiny, barely reaching my shin.

Watt says they’ll be above human height in four to five years, although this is quickly refuted by the forest manager who says it’ll likely be longer. Either way, it’s a long-term project”

The destruction of nature

Higher up the hillside (point 7), the peaty soils became so shallow that there was little for the diggers to scrape. That has not stopped BrewDog’s planters. What had been slowly developing into lichen rich heath, has been turned into a field of wrecked cairns. How long did it take soils to develop on this bouldery ground? 10,000 years since the last ice age? How long will it take vegetation to recolonise these rocks? This is state-sponsored environmental vandalism on a grand scale.

Contrast how BrewDog has done it with how nature would do it if given a chance.

The senselessness of what BrewDog has done

After zig-zagging around the hillside I followed the new forest fence to point 8 on the boundary with the Seafield Estate, not far from the Craigellachie National Nature Reserve managed by NatureScot.

These trees, planted with far less ground disturbance, have survived far better than those planted on mounds, have exposed far less peat to the atmosphere and destroyed far less vegetation. I would still argue that planting here was not justified, given the existing and potential for natural regeneration, but if Scottish Forestry is going to continue to fork out money to plant native trees it should insist on hand planting.

These trees, planted with far less ground disturbance, have survived far better than those planted on mounds, have exposed far less peat to the atmosphere and destroyed far less vegetation. I would still argue that planting here was not justified, given the existing and potential for natural regeneration, but if Scottish Forestry is going to continue to fork out money to plant native trees it should insist on hand planting.What needs to happen

What has happened at Kinrara shows that the Scottish Government’s approach to woodland expansion is completely unfit for purpose and in need of radical reform. Stopping the planting juggernaut is not going to be easy because most people have still not appreciated that planting a few trees locally in disturbed soils around settlements – I do it too! – is a very different things to planting thousands of trees on undisturbed soils like peat. I hope this post helps more people to see the difference and start challenging why we are using public money in this way instead of reducing deer numbers and leaving the rest to nature.

Unfortunately, the Scottish Government has just committed to a new version of the UK Forestry Standard (see here) which sets Britain apart from most of the rest of Europe where planting, deer fences, gigantic tracks and clearfell are the exception, not the rule. If Mairi Gougeon, the Minister responsible, stopped listening to people with vested interests and visited the estates in Cairngorm Connect, on the one hand, and Kinrara on the other, perhaps she would realise the Scottish Government’s mistake.

In terms of actions and policy change the following would be a start:

- BrewDog should not replace the dead trees on site even if it means losing their grant. Instead, they need to put their money where their mouth is and restore the destruction they have caused, starting with the areas of bare and upturned peat. That is likely to cost several £million.

- BrewDog should abandon their Phase 2 plans for the Lost Forest on the Dulnain side of Kinrara now. There is even more peatland on that side of the estate and also important remnants of the Caledonian pine forest (see here).

- The Cairngorms National Park Authority Board should invite the Minister for National Parks, Lorna Slater, to visit Kinrara with them, take a look for themselves at the disaster and consider how they could make their policy presumption in favour of natural regeneration work in future.

- The Scottish Government should sponsor independent research into the impact that the construction of the Lost Forest has had on the natural environment and carbon emissions. That should include a report on how many of the planted trees have died this year and the lessons to be learned from this in the light of climate change.

- The Scottish Government should impose an immediate moratorium on any further planting on peaty soils. They accepted the scientific analysis by Forest Research, which found that ploughing on soils with an organic layer greater than 10cm represented a significant risk of soil carbon emissions, and now need to apply the implications of that research to other destructive forestry techniques such as mounding and scraping.

- The Woodland Grants Scheme in its current form should be scrapped. The money should be redirected into deer control to support natural regeneration in the uplands and planting hardwoods for timber in lowland areas (which have much greater potential to lock up carbon than trees like birch). If the Scottish Government also banned muirburn and left the rest to nature, it could for the first time ever achieve its aspirations for the right tree in the right place.

An excellent forensic account which contains many points of relevance to events elsewhere. Thank you

Excellent detailed report Nick. I’ve not read it all, just sitting up at the top of the Burma Road waiting for the cloud to disappear.

I’ve seen a fair amount of deer poo high up on Gael Carn Mor the last few weeks. I can hear the deer bellowing quite nearby just now. Obviously they’ve been excluded out of the fenced area. I’ve never seen them higher that about 500m in all the years I’ve been up here. Interesting to see if they’ll head down the other side of the hill and into the neighbouring estate near the Dulnain.

Very interesting reading. Where sheep are no longer present I see a lot of natural regeneration where we live just south of the Cairngorms despite high numbers of fallow deer. I agree that wherever possible, which is most places, we should aim to restore nature and fix carbon with as light a touch as possible and allow natural process to lead – especially if they have already begun. Fences only where no other approach is possible, and let’s end this senseless obsession with mounding, diesel and diggers.

Myself & James Rainey gave a talk at the Scottish CIEEM conference about a new approach that prioritises wild trees rather than defaulting to the ‘fence, plant, prep’ model. A flowchart can be found in this tweet but if you want to chat through what it actually involves then feel free to email me, Nick. https://twitter.com/CIEEMnet/status/1709232470250442780

What you’ve highlighted here is everything our framework seeks to nullify about the current way of doing “woodland creation”, which itself is really problematic terminology when we are, by and large, completely neglecting to restore the woodlands we still have left.

You could do with talking to National Resources Wales too based upon my experience.

We are fighting to stop conifers being planted on Borders farmland. Large companies from London are buying up perfectly good productive farms to plant with conifer.I live on a small holding in the middle of one of these projects, we will be completely suffocated by Sitka spruce. Though the agent has been told that this area is not suitable for conifers,they refuse to accept it.

We have a fabulous amount of wildlife,even hen harriers quarter the fields. We have curlews,lapwings,snipe and woodcock,all will go. The Scottish Government are selling Scotland to the highest bidder,they call it it the ‘CARBON CLEARANCES’ It must be stopped!

Aeration of peat whether during peatland restoration or tree planting is extremely damaging both long and short term. Peat should be left strictly alone to develop naturally.

You might be interested in investigating similar commercial operation by Foresight Group’s purchase of Fordie estate near Crieff in Perthshire