The Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) strongly welcomed the Drumlean judgement (see here) and issued a news release following Lord Clark’s initial decision in the Gartmore core paths case (see here), the subject of this post. So far, however, they have said nothing about the decision of the Inner Court of Session, the apex of the Scotland’s judicial system, which was published (see here) just before Xmas despite it being in their favour.

That reticence may be because Gartmore House, who sought the judicial review, are a small charity which appears from its accounts (see here) to operate on a shoestring. Unless its advocate (KC) acted pro bono or it was funded by other interests, the challenge to the legality of the core paths plan is likely to cost the business dearly and the LLTNPA does not wish to be seen as responsible for that.

Last week I explained how Lord Carloway and his two fellow judges used the case once again to describe our access rights as a right to roam and NOT a “right of responsible access” (see here). This post considers why the case may have been brought, takes a look at the significance of the judgement and its implications for core path networks as we approach the 20th anniversary of our access legislation.

Background to the case: the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 and core paths

Unlike England, Scotland has relatively few rights of way and twenty years ago had a much poorer public path network. The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 aimed to remedy that by requiring Access Authorities (Councils and National Parks):

“to draw up a plan for a system of paths (“core paths”) sufficient for the purpose of giving the public reasonable access throughout their area.” (Section 17).

The idea, as described in the statutory guidance (see here), was a very positive one designed to make access easier for all:

“The Act is not limited to the establishment of access rights, but also addresses the need for better provision of infrastructure to facilitate the exercise of access rights. As a result there is growing public expectation that the provision for public access will be improved significantly over the coming years. An important element in the facilitation of access will be the core paths plans to be drawn up by local authorities under section 17 of the Act. Core paths will enable and encourage all members of the public, regardless of ability, to exercise their rights of access.”

There was, however, a caveat in the statutory guidance:

“The system will need to be achievable and sustainable, so will also take account of resource availability”.

Resource constraints and the sheer challenge of creating a coherent core path network meant no-one expected that Scotland’s Access Authorities achieve all the aspirations of the Act in one go. This was one of the primary reasons for the provisions in section 18 of the Act enabling core path plans as a whole, as well as individual paths, to be reviewed.

Establishing core paths plans involves extensive, time consuming and costly processes. The LLTNPA, for example, formally adopted their first core paths plan in 2010, seven years after the Act was passed, initiated a review in 2018, and adopted a revised plan three years later in June 2021. This followed a Scottish Government inquiry into various objections to the plan, including one lodged by Gartmore House.

What prompted the case?

It may seem extraordinary that a small charity, set up to benefit sections of the public, would not want core paths on their land especially when so much of the path network round Gartmore was not fit for purpose being on public roads. As the Statutory Guidance to the Act states:

“Adopted minor public roads or pavements might be designated as core paths where they meet particular needs and are of a suitable condition – perhaps with motorised traffic being either restricted or regulated to provide safe and priority access for non-motorised modes. It may well be that for instance a minor road is designated as an interim measure [my emphasis] to provide a particular link route until a better segregated path can be provided in due course”.

The case makes it clear that LLTNPA staff both consulted and offered to work with Gartmore House staff to balance their interests as a landowner with access rights – well done them! That, however, was not enough as the judgement half-explains:

“The petitioners [Gartmore House] made representations to the reporter. Their principal concern was that the paths would run through their property, close to the accommodation block and land used by visiting groups. As part of the risk assessment for the activities carried out on the land with children and vulnerable groups, the petitioners required to control access. They would be unable to offer the level of assurance required by local authorities under relevant child protection guidelines. Over half of their users would be affected.” [My emphasis].

From this it appears the case may have been prompted by the requirements of local authorities who, as well as being Access Authorities responsible for enabling public access, also have duties to protect children and vulnerable adults. The bottom line appears to be that Gartmore House felt that funding for over half the people using their facilities would be at risk if the charity did not make every effort to resist improved access to their land. Gartmore House was supported in this by another charity, “Green Routes”, whose objective is to provide “teaching and support in outdoor activities to persons with learning disabilities”

In my view this is not social inclusion, it is social exclusion of people who should be being supported to live normal lives which involves contact with others. The case demonstrates just how risk averse local authorities and the voluntary sector have become. Ironically, one of the most important reasons we need to extend core path networks is to provide more safe access routes for children and adults with disabilities to enjoy the countryside – green routes! These groups are likely to be particularly at risk when forced to walk, cycle or ride on a public road.

The judicial review

After the Scottish Government reporter appointed to consider the LLTNPA’s core paths plan had rejected their objections and the plan had been agreed by both Scottish Ministers and the LLTNPA Board, Gartmore House, supported by “Green Routes”, sought a judicial review of the whole process on two grounds. After these were rejected by Lord Clark in the Outer Court of Session, an appeal was made to the Inner Court of Session.

The first ground was strictly procedural. Gartmore House claimed that the Scottish Government reporter should have explicitly considered their objections and the extent to which equalities issues had been taken into account under the Equalities Act 2010. The Court dismissed this, stating that there was no need for Scottish Government reporters to engage in “inquisitorial frolics”:

“The reporter addressed the matters which were raised before him in relation to the public sector equality duty. These concerned the interruption, or disruption, of the activities of children, vulnerable persons and religious groups. The reporter reasoned that the limited scope of any interference, and the ability to temper the effects of such interference by taking temporary measures, was not such as justified a refusal to incorporate new paths which would enhance the access rights of all. The exercise was one of balancing the different weights to be attached to the matters raised [i.e access rights v any potential risks to the needs of vulnerable people] and reaching a planning judgement on where the scales came to rest. The reporter reached a view on the relative weights; a matter which is not susceptible to review. There was no need for the reporter to make a specific reference to the Equality Act 2010 when he had done what was important; addressed the specific problems raised by the petitioners and Green Routes in relation to those with protected characteristics”

Every remaining access officer in Scotland and their managers should breathe a sigh of relief. There is no need for the process of creating new core paths, which is already over-bureaucratic, to become yet more complicated. Those who fund outdoor activities should also take note.

The second ground for the judicial review had much wider implications. The petitioners argued that:

“The reporter ought to have been considering the test in sections 17(1) and 20A(5) of the Act (see here); ie whether the proposals were sufficient for the purpose of giving the public reasonable access throughout their area. The review exercise should have been about whether the original network continued to provide sufficiency; not whether that network could be improved. The reporter ought to have taken into account the original plan. In that plan, the network had been deemed to be sufficient without additional paths within the petitioners’ property [ie Gartmore House grounds]. The reporter had stated that the area was already well provided for in terms of core paths, but that the proposals would provide a significant benefit to the sufficiency. Those words did not mean anything and did not represent the correct test.

The Court also roundly rejected this stating that “It would make no practical sense for a core paths plan to be set in aspic”. The judges reasoning was as follows:

[32] The 2003 Act imposed an obligation on the respondents to draw up a plan for core paths “sufficient for the purpose of giving the public reasonable access throughout their area” (s 17(1)). The respondents did this. The adoption of the plan did not carry with it an assumption, or a presumption, that there was thereby a sufficient core paths network in the area; merely that the identified core paths contributed to the statutory purpose of giving reasonable access and balanced the factors, including the interests of land owners, required by section 17(3). A plan which was put forward for adoption as contributing to the statutory purpose could hardly have been rejected because it did not create a sufficient or saturation level of core paths.

[33] In due course, an adopted plan might be improved; whether by the addition of other paths or the substitution of different routes, provided that the plan, as amended, also contributes to the sufficiency of the network. That is the objective of the provision for review (s 20(1)). The use of the phrase “continues to give… reasonable access” does not carry with it an implication that any previously adopted plan demonstrates the existence of a sufficiency which can never be improved. It would make no practical sense for a core paths plan to be set in aspic. The reporter asked the correct question of whether, under section 17(1), the new plan with the additional paths created a system which again contributed positively to the overall purpose of giving the public reasonable access; balancing in that equation the land owner’s interest. It was not necessary for the reporter to carry out a comparison of the existing network with the proposed new one or to examine whether the network in place was already sufficient. That would be an unduly narrow and artificial exercise; it would run counter to the statutory policy of conferring on authorities a wide discretionary power to review, when they consider it appropriate, whether improvements are desirable in the interests of furthering the objective of promoting reasonable public access. The review exercise involves a consideration of whether the amended plan continues to provide reasonable access, not whether the existing plan was of itself sufficient. The latter might be an argument which a land owner might advance, and it is no doubt a factor to be considered, but that is all.”

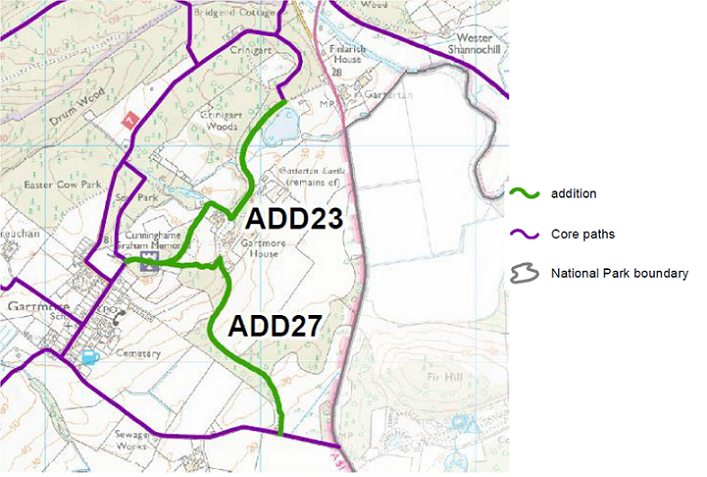

The judgement went on to say how the new core paths, ADD 23 and ADD 27, would improve access in a number of ways.

The significance of the judgement

If Gartmore House had been successful in their appeal, that would have effectively prevented core path networks being improved over time and core paths plans being “set in aspic”. The judgement is therefore really significant. Access Authorities can continue to develop core paths networks through revising core path plans.

Conversely, the judgement would also appear to make it very difficult for any body to challenge a core paths plan legally on the grounds that core paths provision in a area is “insufficient”. This is because review and improvement of core path plans are a “discretionary power” of access authorities.

Although the LLTNPA’s revised core paths plan added 81km of additional core path or 11% to the network (and removed 4km), I argued at the time their proposals were inadequate as they failed to take account of the importance of the recreational experience (see here) and left large gaps in the network (see here). While the decision in the Gartmore House case leaves the door open to the LLTNPA to improve their core path network in future, there is nothing in it that compels them to do so.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Having put access onto a statutory footing, with the creation of the right to roam and the provisions to develop Scotland’s path network, in my view it would be better to keep the courts out of access matters except where necessary to protect the framework set out by the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. In both the Drumlean and Gartmore House cases (the former involving locked gates) that framework for implementing access rights has been at stake and it was right and to the credit of the LLTNPA and the Access Team that they have defended their actions all the way to the highest court in Scotland. That is not the way, however, to improve core path provision.

For the mechanisms for implementing access rights created by the Land Reform (Scotland) Act to work effectively they need to be adequately resourced, whether this is through employment of access officers, support for Local Access Forums or investment in new paths. Much of the infrastructure for supporting access rights has now collapsed and that is not unconnected in my view with the seemingly ever increasing attempts to curtail access rights, whether indirectly through parking restrictions, or directly, by telling people to keep to certain routes or avoid certain areas and the lack of ambition to extend the core path network.

If we want our access rights to remain world class, supported by an extensive path network, politicians need to reverse the cuts to access infrastructure and commit to investing for the public good. The Gartmore House judgement strongly suggests that won’t happen through legal challenges, only through concerted campaigning by local communities and organisations representing recreational and “green travel” interests.