This is the view that the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) planners didn’t want people to enjoy.

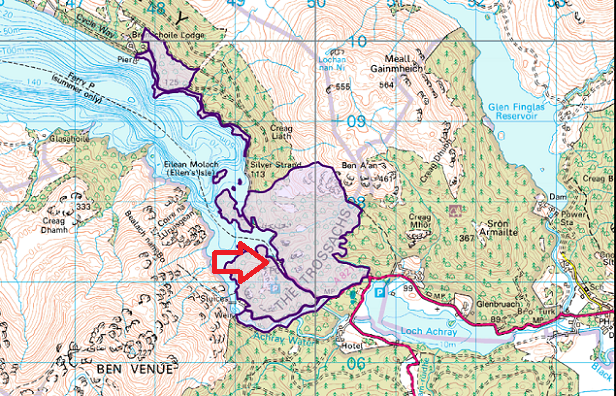

In August 2021 LLTNPA planning officers recommended a planning application from the Sir Walter Scott Steamship Trust to erect a viewing tower accessed by 188m of path throught the oakwoods above Trossachs Pier be refused.

The recommendation was based on the “development” being located in a Special Area of Conservation and the claim that constructing a path and tower would cause significant damage to the site. After being persuaded to undertake a further site visit with Steamship Trust representatives and LLTNPA planners NatureScot withdrew their objection. This, combined with 137 letters of support, many from local community groups, helped the Steamship Trust to convince LLTNPA Board members, after a three and a half hour meeting, to reject their officers’ recommendation and approve the planning application (see here).

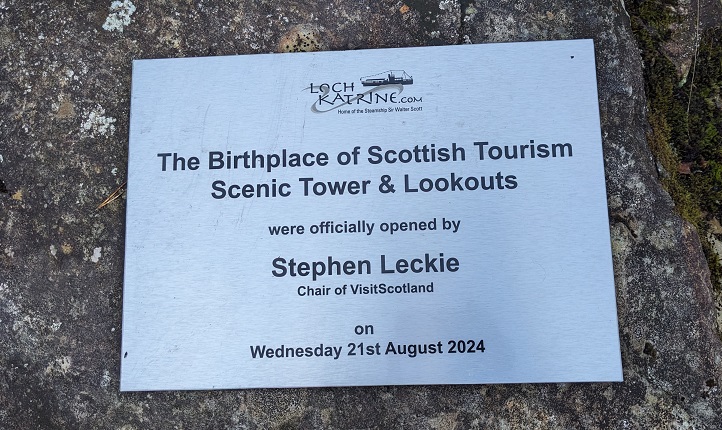

Construction of the path and tower was affected by various challenges caused in part by competing bureaucracies. For example, the LLTNPA and NatureScot wanted the path to have as small an imprint as possible while building control initially wanted it to be accessible to wheelchairs. The work was finally completed this summer and then officially opened by VisitScotland, who had provided a significant amount of funding, at the end of August:

Since then the path and tower has received a fair amount of media coverage, including on the BBC Landward programme (see here – main coverage starts at c7 mins 30 secs).

In 2020 I was asked by James Fraser (Chief Executive of the Steamship Trust and former chair of the Friends of Loch Lomond and Trossachs) to walk over the site and say what I thought about the proposal, including the challenges of constructing a path up a steep slope. I visited again last week as I wanted to see for myself whether I had been right to criticise the LLTNPA and NatureScot’s initial opposition to the development and its impact on the Special Area of Conservation.

The Roderick Dhu Tower as a tourist attraction

With all the controversy about the number of tourists on the NC500, it is easy to forget that Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake created Scotland’s first tourist rush and several hundred thousand people visited the Trossachs in the year after its publication. The Steamship Trust has been trying to make people more aware of that cultural history as well as attracting more visitors to Trossachs Pier, expanding its core business out from operating the Sir Walter Scott. In that they have been very successful, creating places for people to stay overnight (eco-pods and campervan hook-ups see here), extending the opening hours of their cafe, adding toilet facilities (which are future proofed against Covid) and encouraging people to take their bikes by boat to Stronachlachar and cycling back) etc.

With all the controversy about the number of tourists on the NC500, it is easy to forget that Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake created Scotland’s first tourist rush and several hundred thousand people visited the Trossachs in the year after its publication. The Steamship Trust has been trying to make people more aware of that cultural history as well as attracting more visitors to Trossachs Pier, expanding its core business out from operating the Sir Walter Scott. In that they have been very successful, creating places for people to stay overnight (eco-pods and campervan hook-ups see here), extending the opening hours of their cafe, adding toilet facilities (which are future proofed against Covid) and encouraging people to take their bikes by boat to Stronachlachar and cycling back) etc.

The challenge they have faced, however, is the nature of the site. It has steep ground on either side and the end of Loch Katrine is quite convoluted and offers only restricted views. The problem is claiming this is one of the finest landscapes in Scotland – which it is – but then having no means for most people to experience it.

However, just 188m away – and less as the crow flies – there was a fantastic viewpoint which had been used as a lookout (hence the name Roderick Dhu) and also been used by Victorian tourists.

LLTNPA officers in their planning reports tried to dismiss claims that Victorians had visited the viewpoint but, if you look carefully, you can still see the evidence for rock-blasted road that is thought to date back to the late 1700s.

Now why, you might ask, when the popular tourist path up Ben An – a fantastic viewpoint – is just a couple of miles away, is another viewpoint needed? While Ben An is one of the most popular small hills in Scotland and where many people first get to experience hillwalking, its still a hill walk, a major challenge for lots of people. The Roderick Dhu offers an alternative, including for the coach loads of older people who visit the site and the wide spectrum of visitors who are unlikely to either want or be fit enough to tackle the higher hills but want to have a short outdoor experience followed by a cup of tea!

The project was not just about attracting more visitors but as importantly about makiing much more of the cultural and natural heritage of this special place, enhancing the overall “visitor experience” and making a positive contribution to visitor management – giving people something worthwhile to do.

The path has been designed for those markets and purposes in mind.

It was never going to be easy because the ground is too steep but the wooden handrails offer support to those who need it.

When I visited the site in 2020 the views at ground were limited by the birch trees. The tower and raised walkway enable people to get great views though the trees. They are deliberately enclosed to prevent people who may may not have much experience of steep ground from wandering over the edge.

People will make up their own minds of course about how this looks – I’d recommend a visit – but to me it looks well designed and much better than the LLTNPA’s scenic viewpoint at Inveruglas which is now in such a sorry state of disrepair (see here).

The impact of the path and viewing tower on the Special Area of Conservation

A further reason for the fencing was to discourage people from wandering off the path. It has however been designed in a way that makes it possible for people determined to do so – the type of people who used to walk up to the viewpoint anyway – and animals to cross it without hurting themselves.

James Fraser told me that just one tree had to be removed in the construction of the tower and path. As you can see from the photos the larger trees in the immediate vicinity are almost all birch, not oak.

Near the top of the path there were a number of oak saplings, some a few years old but some very recent. Its clear the path has not prevented the oak wood generating and it may have actually helped as the number of visitors is likely to discourage the deer that are responsible for much of the SAC oakwoods being in such poor conditions (I will cover that in a further post).

The faint pathline I had taken in 2020 was very boggy- it followed the main drainage line – and the ground damaged in places. Hence the need for the walkway but I also observed that the vegetation on the ground on either side appears to have recovered rapidly. In other words the path may have indirectly helped improve the condition of the SAC rather than damaging it.

The construction materials for the tower were brought in by helicopter to a flat treeless area beside where the viewing tower was constructed (you can see photos on the Loch Katrine website see here). The vegetation here also appeared to have recoved well – sorry no photo as we caught in a shower.

Being October, the summer migrants to the oak woods had long departed and the red squirrels and jays were probably where the acorns were. I heard a wren, that was all, but saw some good fungi on the trees. Compared to some other developments in SACs that have been granted planning permission in our National Parks – Inchconnachan and the Beauly Denny powerline at the Drumochter – the impact of this development is minimal. It might even enable some people to get a sense of what oak woodland is all about instead of being confined to the car park below.

Protecting woodland in the planning system

It is justifiable to ask why I believe the construction of a path and viewing tower in what is supposed to be one of Scotland’s most highly protected woodlands is acceptable when Flamingo Land’s proposal to build a development in the woodland at Balloch, some of which is of fairly recent origin, is not.

To me the answer lies less in the trees than in the landscape and people’s enjoyment of it. Erecting a large aparthotel and dozens of chalets was wrong not because of the numbers of trees that were to be chopped down – which as I have explained could be easily mitigated (see here) – but because it would have destroyed the outdoor recreational experience, for local people and visitors alike at the gateway to the National Park.

There is a really important difference between visitors looking out from a walkway at nature and having to negotiate their way through a chalet park, however well designed. This argument does not mean we should be constructing paths all over SACs, but they have their place. We build paths over protected bogs, for example at the highly designated RSPB reserve at Forsinard in the Flow Country, so why not through protected woodland?

The problem with the planning system is that it has tended to take a black and white approach to trees. While NPF4 has extended the protections offered previously through Tree Preservation Orders, designation and Ancient Woodland – which is welcome – what actually matters is the extent of good quality woodland. Seen within that context the attempt by the LLTNPA planners to prevent the Roderick Dhu path from going ahead, when other LLTNPA staff are involved in a large project to expand and restore oak woodland around Loch Katrine makes little sense. As I will show in another post these real challenge faced by the oakwoods in the Trossachs is not people but overgrazing by deer.

This broader perspective helps explain why the proposal by the Rescue Boat to chop down trees on the Riverside Site at Balloch to create a new rescue station (see here) should not in itself be seen as a big issue (unlike the flood risk ). While the LLTNPA planner’s reasoning for supporting the Rescue Boat application contradicted the reasons it gave for refusing the Flamingo Land application, they could have avoided getting themselves into this mess if they had considered both applications from the perspective of what people value and enjoy about the landscape.

The majority of people will stay on the path guided by the fence, however the fence does not restrict their dogs from wander extensively either side with what ever consequences.