This is a fuller version of a story in Scottish Mountaineer this autumn, which takes its cue from the long-running “New Twists for Old Hills” series there.

The literal ‘shafting’ is the driving of miles of tunnels through the Ardverikie Munros, linking hugely enlarged lochs for a Pumped Storage Hydro (PSH) scheme known simply and unmemorably as “EARBA” (see here for previous post and here for a link to a Powerpoint illustrating all the current PSH proposals).

The real shafting is of two of our finest hill lochs, with their wildlife, and of several wonderful old made paths, and of the unspoiled ridges and bealachs linking the Ardverikie Three, grand Munros on the Badenoch—Lochaber divide.

These Munros are readily accessible from Moy (Luiblea) on the A86 and thus make a popular long day’s round:

- Beinn a’ Chlachair 1087 – a sprawling blockfield, scalloped by noble corries;

- Mullach Coire an Iubhair 1049 – the proper name as per Munro’s Tables, and now on the 25k map, for one of the numerous Geal Charns;

- Creag Pitridh 924 – the perky outlier on the NW flank of Iubhair.

The first two are linked by the high col of Bealach Leamhain (almost 750m) above which a shoulder will be crossed (at 800m) by permanent heavy-duty access tracks to reach the top reservoir, destroying the old paths which encircle Loch a’ Bhealaich Leamhain.

This “Earba” scheme has been consulted upon locally and is now awaiting a decision by the mysterious Energy Consents Unit (ECU) at Scottish Government. [Highland Council asked the ECU for more time to comment, was refused by the ECU and – to date – has submitted no comments on the application]. But at the big lay-bys on the A86, there is nothing to tell the numerous hillwalkers, fell-runners, mountain bikers, and wanderers of this enormous project, who come from far and wide, and will never have heard of it until they see it being constructed. And I might never have known either, but for a colleague who persuaded me to visit while these hills and lochs were still pristine.

Lochan na h-Earba is not one of those names that rolls off the tongue let alone sticks in memory. Yet it is over 6 km long, more than half the length of Loch Laggan, if divided half-way by a remarkable large fan called Am Magh, spewed out in spates by yet another Moy Burn (magh/moy just meaning ‘the flats). It is handsomely and ruggedly framed by the two Binneins, Shuas and Shios, on the north, and by Creag a’ Mhagh and Creag Pitridh itself on the south.

I had not been this way before before, and cannot recall even glimpsing it from surrounding Munros, concealed as it is in its narrow trench. The loch is open at both ends, as it occupies a glacial breach of the Spean—Spey divide: water flows east through it only to return west via Loch Laggan, such are the vagaries of the ice-baffled River Pattack.

My vague impression of “Earba” was thus of a probably bleak wind funnel of a side valley that didn’t go anywhere I wanted and had no obvious attractions in itself. As I am finally enticed in there, over a fine weekend this May, how unhappy I am to be confounded. Nor had I realised that Earba is known to the cognoscenti for wild camping, perhaps the best spots in this entire area. So we have decided to camp in here, to listen out for the snipe drumming of a night, and to shorten a hill day in the uninvited company of Mr H, my newly-acquired hernia. The open west end has good grassy swards, and a fine sandy beach, but is a bit public; indeed, two tents are there next day. We bike on along the good track to Am Magh, where the lush grassy fan attracts another bike-camper; we find a secluded spot above the gravelly shore. This we agree is one of the loveliest places we have ever passed a night, in complete tranquillity, embraced by a quartet of striking hills – Shuas of course sporting the Ardverikie Wall, Shios our evening grandstand for the unimaginably long skyline of Meagaidh, a gentle sunset behind it. And yes, we do eventually hear the snipe.

Likewise, in the high corries above, Loch a’ Bhealaich Leamhain rolls even less freely off the tongue, sticks even less readily in the memory. How many of those who glimpse this pearl while doing the Ardverikie Round could name it? Yet it is finely set, below the bealach between the Big Two from which it takes its name, the largest corrie lochan in the Alder massif. It has a distinctive clean-lined pear-shaped serenity that has captivated many a photographer, notably when black within white snows, or glimpsed through mists.

And so we set out to pay possibly our last respects to its serenity. And of course we will make a New Twist out of it while we are at it. Here we must mention a fresh field of research – “stalkerpaths” as we like to twist their name too, making the point they are properly called ‘pony paths’, made chiefly to get the carcasses off the hill more efficiently – and for recreational enjoyment for non-stalking guests (as the redoubtable Grampian Club and Munro Society have been first to hear, both thanks to the enthusiasm of Alf Barnard). Ardverikie has one of the very finest webs of these made paths, round all the hills and through the passes. It has just two short spur paths nipping up onto the Munros, both late extras, for us to explore – are they still go-able ?

From our tent door, we stroll up to the apex of Am Magh, and head up a little-used ‘stalkerpath’, mostly followable despite the ravages of Moy Burn spates. It climbs out above the ravine heads to become a splendid ruled line, rising up the moor and slanting in to a high col, where it carries on over and down into Pattack. Our short spur is clear – it starts as a well-made bench behind the skyline, crosses over at the foot of the north shoulder, and traverses into Coire an Iubhair at waist height, just below its craggy wall. In the corrie head, the path bears up the steep grass to emerge on the brow of the Mullach plateau, between Munro and Top: at 1080m, this is a rare high-riser. Or not quite – as is not uncommon, the path stops just short, in a little hollow, perhaps with a scooping and revetting of a seating place sheltered from the sou-westerlies.

This is one of the most delectable of such made hill paths – perhaps intended more for walkers than ponies, with one awkward spot where it has been chiselled into the base of a crag. Every variant detail for getting water across the path is on display. There are no traces of human passage – the deer keep it handily alive, as so often, in a neat turning of tables.

And there they are, all 160 hinds and calves, on the long residual snowbank which buries the slanting notched line – for these paths were of course only really required for the July-October Highland Season. The deer are drifting to and fro to keep cool like a murmuration, only leaving as we near, down a mansard-slope steepening so much that the less sure-footed calves slip and slither comically down it, ending in heaps.

I have predicted that our way might be barred thus, recalling a visit decades ago, when we opted to go up the north shoulder. But this time there is a path to be vindicated, no turning back… The main snowbank is frozen hard, impossible to address without spikes, and it runs into the crags at each end, unturnably. But a little outcrop suggests a weak spot midway, thinner and with less of a steep toe — my colleague kicks steps up it which, as usual, are too widely spaced for a stiff old crock to avail of; bare hands manage to dig sufficient holds to progress up it (with Mr H keeping himself well zipped).

Looking down where the path disappears into the snow, you would not dream of descending what looks like a cornice precipice.

In our exhilaration, we forget once again to take in the Top, and cross over the sturdy Mullach, delighted with a “New Twist” worthy of the name, despite its following a made path almost to the top. Fell runners come and go; hillwalkers are on Beinn a’ Chlachair already. Barring the forestry filling the Spean basin, and some giant turbines glimpsed on the distant, unhappy Monadhliath, our long views all around are free of modern intrusions, the vast canvas of the Highlands as they should be, balm to wearied souls.

And now, that pearl of a lochan comes into view. We descend the block slopes, and briefly join the ‘Ardverikie Round’ to cross Bealach Leamhain, where another fine stalkerpath rises to a notch at 800m on the broken nose of Beinn a’ Chlachair. The Pony Path – for so a dump of horse dung declares it still to be – here follows a splendid rocky bench, with a delicious spring bubbling onto it through saxifrage beds, nectar in this dry spell. Sadly, Mr H says he’s seen quite enough for today, needs a lie-down, so we pause on the brow to contemplate the imminent extinction of this priceless lochan, then turn back. Yet another path – still good in places – takes us over the Creag Pitridh col and down Coire a’ Mhagh to our tent.

EARBA PSH

When the plans for Earba were submitted, Mountaineering Scotland’s email newsletter invited comments on the biggest Pumped Storage Hydro (PSH) schemes yet proposed in Britain. Apparently, views were divided rather evenly (as so often happens) between those who welcomed a noble sacrifice in the cause of climate change targets, and those who didn’t.

“Earba” has three key components impacting our mountain landscape :

- The twin lochs of Lochan na h-Earba will be drowned by large dams either end of the through valley, raising the top water level by over 20 m. Our amazing, special Am Magh fan will disappear, as will the haunts of sandpiper and of snipe¹, along with the best sheltered winter grazings for those native inhabitants, the wild deer. And all these good camping spots will vanish, irreplaceably.

- As for that pearl, Loch a’ Bhealaich Leamhain, a massive dam 100 m high protruding way out from the natural line of the hills will raise it almost to the level of the Bealach. That’s three times the height of the massive-enough Cruachan (The developer’s ‘visualisation’ shows only the top quarter of the dam, with a brimful lake – not the daytime drawdown scar – behind a metallic-sheen curve of Italian sports-car elegance). This dam will catch the light and the eye, prominent from the near Alder massif and the far Drumochter-Gaick rims,

- Most damaging of all but seldom realised until they’re there – access roadways of industrial scale, for construction and maintenance, zigzagging all over the slopes of Creag and Coire Pitridh, slicing across Bealach Leamhain and that notch, and destroying the pony path along the rock shelf with 8-10 metre deep cuttings probably 15-20 metres wide (the developer’s ‘visualisation’ – well, there isn’t one; no-one seems to have noticed this wee detail). All walkers crossing the Bealach between the Big Two Munros will have to cross that track and skirt the clutter of installations controlling the huge pipes linking the two reservoirs. Construction scars will persist for years – especially as enforcing any restoration conditions seems impossible these days.

Save the Ardverikie lochs and corries

A huge antique wallmap in the estate office at Ardverikie manages to depict lochs Earba and Leamhain for what they indeed are – the most striking features in this noble mountain landscape, hard on the main watershed of Scotland (pre- its Ice-age breachings). But sadly their names cut little mustard (although not even the magic of Etive could save that glen from run-of-river despoliation).

On delving into their meanings,

- earba is an obscure term for female deer, such as would find succour along its shores,

- iubhair is the yew – which could hardly have grown up here and ineed is not known on Ardverikie, wild – but could also mean yew wood, as in the bow or even the arrows; could some bow, lost, broken, buried, triumphant, have given us this legend-name ?

- leamhain is the elm, even more implausibly – ah, as so often, the place-naming efforts of the OS First Edition have been over-ruled, it was originally Bealach Sleamhainn – the slippery pass. As indeed it could well have been, before the pathmakers eased the way. And indeed, one for slippery customers to smuggle things through.

Save the Ardverikie Munros

Indeed, it’s not just the lochs: with all the heavy-duty access roadways, at almost no point on the classic round will you not have this scheme full in your face. You will be in the midst of an Energy Production Zone. The regular way off Creag Pitridh, down grass and boulder slopes, will now follow industrial zigzags. Even in depths of winter these vehicle tracks will be in frequent use – imagine what it will take to keep that rock shelf cutting free of snowdrifts (why they cannot access the Leamhain dam from Pattack side, which already has a fullscale road to the big new run-of-river hydro there, they will not say).

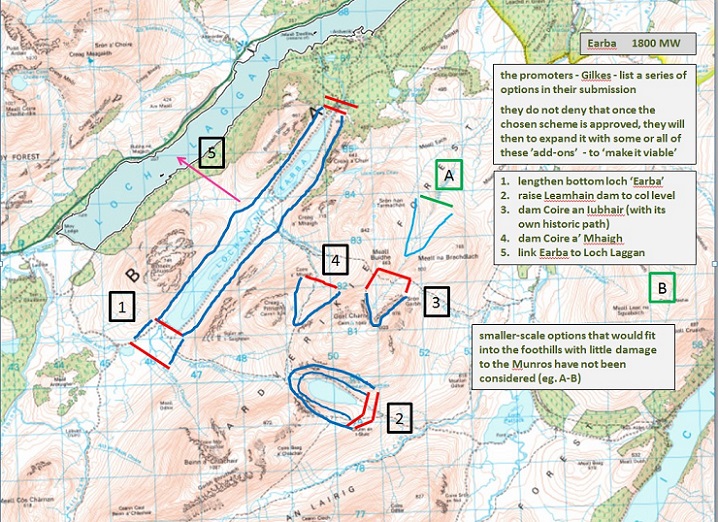

And trust us, it won’t end there. Buried deep in the wheelbarrow-load of documentation is a page on the alternative options they were required to evaluate. These include:

- lengthening the Earba reservoir both ways, with the SW dam projecting well out into the hummocky moor and taking in a small loch there;

- raising the Leamhain dam to take its shoreline right up to the col

- and – drowning our beautiful Coire an Iubhair, with three dams cutting off overflow points around its apron – our ‘New Twist’ path vanishing save where it emerges below that snowbank.

Also considered – (4) a third hill reservoir, in Coire a’ Mhagh, (5) linking Earba itself to Loch Laggan.

We predict that, sooner or later after ‘Earba’ is consented by the Energy Consents Unit (no scrutiny by public inquiry or by parliament, just a ‘sign-here’ in some minister’s overnight box), the developers will be back. They will argue that to make it viable, they will need to increase the capacity of the project – making full use of the large lower reservoir capacity, the costly underground power cables, and the new switching station at Laggan linking to Beauly-Denny (so convenient – this is why this scheme is a front-runner).

On being asked whether these ‘extras’ might come forward – as we see with windfarm extensions – the developers could not deny it. To quote: “our current focus is on the existing proposal”. So, no corrie, no glen, on Ardverikie will be safe – and the precedent will have been clearly set, nor will any Munro anywhere, remember how ‘Run-of-River’ went like wildfire.

— — —

Of course we all agree that resisting global heating is vital, and pumped storage can play a part to play in balancing fickle renewable sources and demand surges (there are other means). But the Ardverikie Three are a major Munro group visited by thousands – they should not be casually sacrificed, at the whim of a particular landowner and developer joining forces to promote ‘Earba’. Bearing in mind the same developer has an even more blatantly conspicuous mega-PSH scheme in the heart of the Quoich Munros, ‘Fearna’.

This is not the place for all the arguments – see the previous blogpost and also one by Jane Meek on UK Hillwalking (see here). But please don’t imagine that a handfuil of mega-PSH and we’re there at Net Zero, job done, relax, enjoy all the remaining hills. Because it is a rapidly moving target, as electricity demand goes exponential – think data storage centres, AI, bitcoins, and more as yet unimagined to come. So, as ever, just ‘follow the money’. Are the shafts being driven through the mountains really motivated by ‘saving the planet’ – or are the mountains basically being shafted for profit, and their lovers along with them ?

— — —

A handsomely illustrated volume, the Memoirs of Finlay Mackintosh, stalker on Ardverikie and Ben Alder in its heyday was published in 2020:

We glimpse how these paths were used by the garrons, and the deer stalked from way above them. And we learn that a young master, back from WW1 and out for a picnic-camp with friends, suggests that these short late additions be cut, just to make it easier to nip up the two ‘home Munros’. My own diaries remind me that back in ’87, after we were were barred from the Iubhair one by that late snow bank, we relished that remarkable rock-shelf-path² – from which our last glance back at Loch a’ Bhealaich Leamhain was a memory of glittering ripples.

We glimpse how these paths were used by the garrons, and the deer stalked from way above them. And we learn that a young master, back from WW1 and out for a picnic-camp with friends, suggests that these short late additions be cut, just to make it easier to nip up the two ‘home Munros’. My own diaries remind me that back in ’87, after we were were barred from the Iubhair one by that late snow bank, we relished that remarkable rock-shelf-path² – from which our last glance back at Loch a’ Bhealaich Leamhain was a memory of glittering ripples.

There is another handsome, illustrated volume³ recently published – “Ardverikie – Castles in the air”. It draws on the old records to chart the assembling in around 1870 of half-a-dozen Lochaber-Badenoch properties into one of the largest sporting estates ever. One might imagine that Sir John Ramsden – wealthy beyond dreams simply from owning most of boom-town Huddersfield – might not be the most admirable figure. Yet the book opens with his letter to his mother, at age 38, breaking the news of his ambition:

My dear Mother

We are building such a delightful Castle in the Air that … I can bottle it up no longer …but you must be mute as a fish and not tell anyone a word about it. … [a castle] and a square block measuring 12 miles every way, and beautifully set in and surrounded by lakes and mountain ridges so that there would be little room for further coveting … And then, besides the beauty & vastness of the whole thing it has the charm of being absolutely untouched – there is not a public road or footpath anywhere in the forest, & the woods have never been improved or cut down or done anything to. It is a real slice of primeval wilderness. No stone wall or bobbin-mill, or other barbarities of civilization…

Most Affect’ly,

JWR [John William Ramsden – bold type added]

What would he think of his successors, as they go about curating his great, ‘absolutely untouched’ treasure – now ours to share – with such casual disregard for his values, his dreams ?

For “Ardverikie” – a name well-known from Monarch of the Glen days and many a film seeking that ‘iconic’ Highlands backdrop – has a seductive website extolling the glories of its landscape heritage, and of its being a rare estate still in the hands of its ‘founding family’.

Footnotes

[1] the developers’ own survey suggests there may be just three nesting pairs of snipe here, how many on the whole of Ardverikie who knows, but this – with Loch Pattack – is the place you would go and hope to hear them; they will not re-establish on the artificial reservoir shoreline worn into loose peaty debris banks.

[2] both paths – across the flanks of Coire an Iubhair Mor and Coire a’ Bhealaich Leamhainn – have now been registered as of historic interest by Canmore (HES) and by Highland Council (HER)

[3] both volumes created by Richard Sidgwick, former factor to many West Highland estaes, including Ardverikie and “Sixty glorious seasons” published with help from Wild Land Ltd.

What increasingly worries me about these large-scale proposals is the lack of transparency, democracy and accountability that lies at their heart.

It may well be that this scheme, in this place, is urgently and genuinely needed. How will I ever know, when the decisions leading to it’s creation and consent are hidden and deliberately kept separate from forensic public scrutiny?

What I am absolutely certain of is that leaving our landscape, energy production, infrastructure finance and energy security in the hands of lairds and developers, doing as they wish, is utter folly which will cost this country’s people sore and long.

I agree

It’s a speculators free for all as far as renewable energy schemes are concerned currently. No strategy and precious little oversight. All about the money under the guise of ‘saving the planet’. And this is happening across the Highlands and, indeed, lots of other parts of rural Scotland, from Shetland to Galloway, and from Skye to Deeside and the Mearns. Nowhere is safe.

Thank you for summarising so accurately our real concerns, your comment, or similar, placed as an introduction at the start of the article would helpfully guide people as to the key issues being highlighted in this important but very lengthy post.

K

It is happening in Wales too – see the item in Guardian 18 Oct about Rhaeadr y Cwm and Afon Cynfal proposed hydro – the last free flowing river in Eryri. When will people recognise that you don’t save the planet by despoiling yet more of it!

Often forgotten with these schemes is the many miles of pylons required to take the power to where it is needed. All across the Highlands are schemes, increasing in number where hundreds of miles of pylons are planned. In my local area we have been fighting turbines, pylons, micro hydro, even hydrogen plants and now massive battery storage plans. All because power production is planned where it is not needed. Oh yes, and it’s just a coincidence that not so many folk live here.

Thank you for your input

It’s appears amazingly co-incidental that the John Muir Trust, who would have been one of the main prominent objectors to plans like this, is now out a shadow of it’s former self, for reasons that mystefy most. ed

So, Bill and Beechgirl, what’s your solution to the climate crisis? What’s wrong with the principle of Pumped Storage? Cruachan generates hydro-electric power during the day, pumps the water back up the hill during the night, and no-one even notices. So many reservoirs built in the 1950s and 60s for one-way generation and no-one is now saying they should be dismantled. And their access roads and tracks are accepted now as part of the landscape. The Upper Glen Nevis proposal in the 70s(?) is the obvious example of a bridge (or dam) too far but this is a green solution. Your favourite view or camping spot might be affected but what are you suggesting is the better way? And I’ve climbed Ardverikie Wall and the surrounding Munros, and mountain biked accidentally into the yard of the castle so I fully appreciate the area’s special qualities.

It is heartbreaking to think that the Scottish landscape might be so carelessly changed with no consultation. It will have an incredible impact on the wildlife and environment. People do walk these hills and camp out and have done so for years. This environment could be seen as an essential ingredient in the rewilding campaign that is now seen as vital to Scotland’s environmental recovery programme.

While the entirety of this proposal seems horrible, I genuinely don’t understand why this has been drawn up using the small but utterly beautiful na h-Earba lochans as base reservoir, rather than the much larger Loch Laggan which is already level-varying (I think) due to the Laggan hydro? Mystifying. It all still falls within Ardverikie.

Agreed!

Having recently visited Loch Tummel and surrounding areas, we were a bit surprised at the devastation around the Hydro Electric scheme caused by heavy construction traffic. What is worrying is the total lack of public information. The proposed development of Adverikie is neither needed or wanted and is being done to satisfy English needs! Are we really going to sacrifice our pristine lochs at the behest of another country? Do we want to travel north and see the skyline polluted with pylons?

I sympathise with most of your views.

However, in my opinion (of dubious weight in national affairs) England is not really “another country”, we are all The United Kingdom, despite the best, and failed efforts of the SNP.

They have been the driving force for lots of green power in Scotland, not some fictitious “English thing”.

It’s not fictitious at all! Energy produced by countless windfarms, Hydroschemes etc in Scotland is piped down south then England takes it all and sells it back to Scotland at the highest rates in Europe.

Hi Jonathan, I think its really important when we talk about energy we get our language right, oil and gas may be piped, but not electricity which is transmitted. The differences are important because while gas and oil can be stored in pipes, electricity cannot be stored in wires. I would be interested to know what evidence you have for electricity produced in Scotland being transmitted down to England and then back to Scotland but, given my understanding of the grid, the only way that could happen is if England has means of storing electricity which Scotland doesn’t, for example electricity is transmitted down to England, stored in batteries there, and then transmitted back to Scotland when we need it. That seems unlikely as at present, for example, it is Scotland that has most the pumped storage capacity in the UK. What I think is more likely to happen is electricity produced in Scotland will be stored in places like the proposed Earba scheme and then transmitted down to England. Any claims about Scotland selling electricity to England or vice versa need to take account of the fact that most of the electricity generation capacity in both Scotland and UK is owned abroad or being bought up by foreign companies, a recent example being the purchase of the proposed Red John pumped storage scheme by the Norwegian based company Statkraft

Do we know if there are any plans for similar schemes in the Lake district?

Not yet but

“While there aren’t currently any pumped storage hydro schemes in Cumbria, the region does have the potential for several new projects in the future,

particularly in disused quarries or other suitable locations. The combination of hills, mountains, and lakes make Cumbria an ideal location for pumped

storage schemes. Cumbria has several locations that could be suitable for pumped storage

projects. Some of the potential sites include:

1. The Lake District: The Lake District has a number of reservoirs and lakes that could be used for pumped storage projects.

2. West Cumbria: The hills and mountains in West Cumbria provide potential sites for Pumped Storage projects. There are several existing water reservoirs in the area that

could be used for Pumped Storage.

3. Abandoned quarry sites: Quarry sites are an additional location that could potentially be repurposed for Pumped Storage facilities. There are a

number of quarry sites dotted across Cumbria, offering a starting point for feasibility assessments”

Personally I believe large scale pumped storage like Earba will not be promoted in the Lakes (or Snowdonia) as there would be so much public outcry it would raise awareness of the damage these schemes will cause and that could scupper projects in Scotland.

I’m not hearing any better options from those commenting. HSP is a green energy. What would Nick prefer? Another Windscale, currently a massive risk on his doorstep and poisoning the Irish Sea for decades? What’s a better source than HSP of the energy the country needs?

Non-fossil fuel energy is not necessarily green energy, both from a carbon perspective – the carbon emissions required for its construction – and from the perspective of the natural environment. Those ungreen elements of pumped storage schemes vary depending on where such a scheme might be located yet, instead of taking rational decisions about this through central planning, government is leaving it to the market. Do you trust the market to take decisions on green rather than financial grounds?

I think it is worthwhile reminding everyone of the 36 construction workers who were fatally injured during the 6 years it took to construct the existing Cruachan pumped storage station.

In fact, what is now not generally found on public record, is the abandonment of the scheme,deemed “impossible”, following collapse of a platform being used to drill upwards from the turbine hall. It was this catastrophe that the killed so many.

A German Austrian tunnelling company was brought in a year after the accident to “save” the project as subcontractor. They offered their newly proven engineering solution on a ‘no -cure, no-fee’ basis. It was this experienced tunnelling firm , Zeigler, which succeded in the 65 deg near vertical 350 meter shaft bore. They had a newly developed system of massive hydraulic cams to support a shaped drilling platform. The platform incorporated a steady pour of grout,backfilling to secure a concrete segmented tube,sections lifted into place and formed beneath the platform as it tunnelled upwards through the mountain. The mined rock fell away below.

The station has repaid the £ investment many times since, of course. But to try to claim that the energy required to construct any scheme of this sort and scale somehow makes it “green” is just so much industry propaganda.

It was only ever justifiable in an age when newly built nuclear power stations began to deliver so much excess power during the night. This excess situation is now partly replicated in this modern age while nightime windstrength has clear potential to deliver far more power than might be needed. Of course individual wind towers can be set to generate no power at all, or switched back to full output, so very swiftly indeed,, and power once generated can be exchanged via subsea cables to lands where excess electric potential exists. So why today we hear constant calls for ever more pumped storage, including a doubling of capacity at Cruachan,becomes somewhat mysterious .

Should Scots of the future deserve to have had their landscapes and the natural heritage of pristine places so permanently trashed in this way?

Sadly, you have failed to understand why pumped storage (or an equivalent storage scheme) is required. The wind does not always blow, sometimes for days at a time. Scotland’s (and England’s) nuclear facilities are closing. Perhaps there should be a tick-box on everyone’s electricity bills where you can indicate that you do not wish to draw power when the grid is struggling to supply it? That would help.

My understanding is that the Lochan na h’Earba scheme could supply sufficient power to supply the whole of the UK for around an hour. As you say, we may need power for days so, to cover five still cold days, that is approx 120 mega dams most of which would have to be in Scotland due to our topography. The carbon cost of that in concrete would be staggering. If pump storage is essential as claimed, we are in deep trouble. We are heading for grid meltdown because no politician is thinking through the issues but relying on market solutions.

Ed Minibrain strikes – but this will be the first of many that this idiot will try to engineer.

And now this: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-scheme-to-attract-investment-in-renewable-energy-storage

In line with the above article, how do we align the move from fossil fuel use with saving the planet?

Those who are ignorant (and I include myself) of the nuances, hidden wheeler dealing and obscurity of planning, executing and applying rules and judgement need some help here.

It’s fascinating and frustrating seeing schemes like Earba being pushed, when research suggests there are several much better potential sites in Scotland which could store much more energy at lower cost and potentially impact. The area is such a special one which will be vastly changed forever, and so many dams would be needed for it.

While we need storage, looking for the most effective site would seem to be very valuable.

https://re100.eng.anu.edu.au/pumped_hydro_atlas/

A very worthwhile article indeed, but please don’t pluralise Gaelic as you do English, and please don’t try and be the judge of whether Gaelic names roll off the tongue or not.

Good luck with your campaigning.

Alasdair Maclean

I’ve seen black throated diver at Earba (and red throated diver at Fearna). Such a shame that they will be lost from these areas. All these fluctuating lochs will become unsuitable for divers to breed on.

I feel conflicted and I guess there will be no perfect solution. As a munro bagger I don’t want to see such beautiful areas trashed (especially Spidean Mialach which was one of my favourites) and as an ecologist I don’t want to see habitat for rare species lost. However I fear what the alternatives may be. Other schemes which involve building even more new access tracks instead of upgrading existing ones? Damming diver lochs in even more remote areas which don’t already have disturbance from hill walkers or estate vehicles?

I’ve noticed some people’s comments saying that no better alternatives are being proposed but the Loch Ness PSH projects are better, Coire Glas is better, Cruachan is better. It’s just that the negatives associated with Earba and especially Fearna (imo) are particularly negative.

Hopefully all aspects will be considered for these projects before they get approved, not just the financial side of things.

In principal I’m supportive of pumped storage schemes, but not this one. Amongst outdoor enthusiasts this little corner of the Highlands is a bit of an open secret. Apart from being on favourite routes for mountain biking [like the Badger Divide], being on route to Munros, a great camping spot and swimming spot. Loch an Earba is probably unique, to the best of my knowledge, it’s the only loch that has been completely divided into two separate lochs by an alluvial fan. The proposals are heart-breaking.

I believe that some existing reservoirs should be re-engineered to pumped storage schemes and that this avenue should be exhausted before any new schemes.