On Saturday I was involved in a demonstration organised by the Right to Roam campaign at Scots Dyke, constructed in 1552 to delineate the border between Scotland and England. As one activist straddling the border put it, this foot has a right to be here, the other one doesn’t. The differences in access laws between the two countries are unjustifiable from a human rights perspective.

At the event a group of us handed over a draft right to roam bill, based on Scotland’s world-class access legislation, to activists in England. They were keen to learn from our successes. It is over twenty-five years since I was involved in a meeting between recreational organisations from the two countries at Ullswater, in the Lake District. There we failed to persuade our counterparts in England to support the right to roam. Now the ground has shifted and rightly so. While we still have significant access problems in Scotland (as frequently discussed on this blog), they are not about the legal framework or the creation of a statutory right of access, rather the problems stem from failures to implement the law.

Both Channel 4 News (see here) and the Guardian (see here) provided excellent coverage of the event and what it was about.

The English landowners arguments against access

The arguments given by the Country Land and Business Association (the English equivalent of Scottish Land and Estates) to Channel 4 against extending creating a right to roam in England are worth considering as they were so ludicrous:

- First the CLBA claimed England is different because of its much greater population (they claimed nearly 70m but that is an approximation of the UK figure, which includes Scotland, and the actual number is c56m). The implication is that people, by their very existence, are bad for the countryside and should be kept out. This conflicts with the UK Government’s commitment earlier this year that everyone in England should live within a 15 walk of nature because there are so many people with so few places to go for their physical and mental health.

- The most important argument against this from a legislative perspective, however, is that generally people, even in large numbers, are not a problem. Proof of that is visible in any city park where formal flower beds survive, flourish even, despite the thousands of city dwellers. Often there is not even a “keep off” sign.

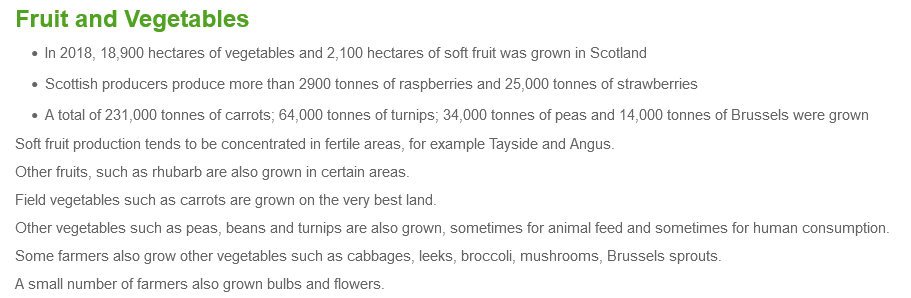

- Despite this, the CLBA spokesperson was much concerned with the implications of access rights for crops and “food security”, claiming that Scotland’s rights are not suitable to England because of a greater diversity of crops south of the border. This claim may well be true but, according to the National Farmers Union of Scotland (see here), in 2018 a fair range of fruit and veg was still produced north of the border :

- Moreover, with less than 9% of the population of the UK, “more than 12% of the UK cereal area was grown in Scotland”.

- And as for livestock, according to the NFUS, Scotland has “almost 30% of the UK herd of breeding cattle” and more than “20% of the UK breeding flock” of sheep.

Clearly, the existence of the right to roam hasn’t stopped Scottish Farmers farming, whether this is growing fruit and veg or keeping livestock. That should not be a surprise to anyone who understands that Scotland’s right to roam is based on the basic principle that you can go almost anywhere (not people’s gardens etc) so long as you do not cause damage. The converse to that is Scotland’s right to roam did not remove any of the laws that rightly protect farmers and farming so that, if someone tramples over a crop for example, they are committing a criminal offence. The conclusion is that access rights are quite compatible with farming in Scotland and would be in England too.

- The CLBA’s third claim was that a right to roam would be incompatible with the need to plant trees to combat climate change. This is best described as brass neck! The main reasons for the lack of woodland in England and Scotland is the consequence of overgrazing by sheep and deer (a major problem now in England too) and muirburn, all activities managed by landowners and has nothing to do with visitors to the countryside. In fact many visitors, if given the opportunity, would love to plant a tree in the countryside. One suspects the real explanation for the CLBA’s stance is they do not want people in woodland because of shooting interests.

Landowner double standards and learning from King Charles

Historically, a number of landowners and farmers have owned land in both countries and there are some interesting cases of landowners tolerating access in Scotland but trying to prevent access in England. A prime example is Alexander Darwall, the very rich man who as I predicted is now appealing the second Dartmoor Judgement (see here). Mr Darwall also owns an estate, Suisgill, in Helmsdale in Sutherland whose website features a graphic referring to the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (SOAC)!

While the quote on access and deer is selective and taken out of context – there is a whole lot more advice on access and deer management (see here) – the key point is that in referring to SOAC Mr Darwall appears to be implicitly endorsing ALL the advice in it, including that on camping. So why is he taking such a different approach in England?

The Royal Family are the most influential landowners in the UK and own land north and south of the border. A few days ago there was a story about King Charles (see here), who has been up in Balmoral, meeting some mountain bikers while out for a walk and complaining to them about the midges. One suspects that it was not just the walk but the chance to talk to ordinary people that did him good. The point is, however, that if people can exercise their access rights at Balmoral without threatening the safety of the King (the story does refer to the presence of soldiers) or with his ability to enjoy his property, it can be done anywhere.

Among the Land Reform proposals the Scottish Government is currently considering is a public interest test when it comes to people buying large areas of land (defined as over 3000 hectares). Part of that, I would suggest, should include checks on whether prospective landowners respect Scotland’s access rights. Had Mr Darwall had to make such a commitment before purchasing Suisgill in 2016, the Dartmoor cases might never have happened.

Ramblers on the run?

Rather than supporting the Right to Roam event, Ramblers staff were banned from attending and the London office issued an extremely negative statement to the Guardian which was reported as follows

“But there are splits in the English access movement: the Ramblers group believes the English act can be enhanced to include access to watersides (but not on to the water), to woodlands and some downlands. England’s very large number of rights of way makes Scotland’s model unsuitable and unnecessary, and would undermine the “trust and consensus” built with landowners, they argue.”

This not only sells watersports (swimming, canoeing, sailing) down the river – the British Canoe Association supports the right to roam – and leaves the position of cyclists and horse-riders unclear, it is incompatible with what the Ramblers own website describes as Scotland’s “world-class” access rights:

The Ramblers in England also don’t appear to appreciate their position is incompatible with their previous arguments – still on their website (see here) – for what they call the freedom to roam:

“The freedom to roam means you can walk in open landscapes without fear of trespassing. You don’t have to worry about sticking to paths. You can walk without constraint, setting yourself, and your mind, free…………………..An expanded freedom to roam will give more people the chance to walk in nature close to home”.

But not, it appears, the right of ramblers in England to step off a right of way through fields to sit under an oak tree or take a closer look at something of interest “without fear of trespassing“. According to this new doctrine, people should only have the right to enjoy nature from afar. There is no justification for restricting people to paths, whether rights of way or not, and we won all those arguments in Scotland 25 years ago. The crucial point is people should have a right to go anywhere to enjoy nature so long as they don’t do damage.

I have been a member of the Ramblers for something like 30 years because I believe that in the long-term they were committed in principle to extending access rights across all land and water on the Scandinavian model (a policy which was adopted at one of their conferences). It is very sad to see their branch office down in England being so out of touch and losing their way so completely.

The makings of a right to roam campaign in Scotland

I had not attended such an inspirational event about access since the Land Reform Act was passed in 2003. It was not just that people from England wanted to learn from Scotland or that activists from both sides of the border have begun to work closely together – something that Andy Wightman remarked has become increasingly rare at the grass roots level – or that people were obviously enjoying themselves.

For me, what was really inspirational was the number of people attending from Scotland, a younger generation who really value our right to roam and who are concerned it is being eroded through a mixture of neglect and maladministration. What is more they want to do something to change this for the better, inspired by what the Right to Roam campaign has been doing down in England.

Among the issues we discussed were the closure of the Radical Road in Edinburgh (over five years now), the Cairngorms National Park Authority’s proposal to restrict access in an attempt to save the capercaillie, the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority’s camping management byelaws, the proliferation of no camping signs across Scotland, the Pentlands Hill Race (called off this year due to the withdrawal of co-operation by landowners) and charging for access.

There are plenty of other examples of access activists in Scotland banging their heads against a brick law when it comes to having our access rights respected. All this provides plenty of potential and justification for some direct action on the model developed by the Right to Roam campaign in England. I will use parkswatch to do all I can to support that.

I disagree that access problems in Scotland are “not about the legal framework”. A look at the Scotways archive of previous legal cases relating to the Scottish access laws shows that most are about people using the provisions of that law to restrict access (and that their chances of success apparently depend on how rich they are). It could be argued that the “legal framework” also encompasses the larger issue that rights exist in theory but are not enforced because the legislation failed to adequately address how this would be done in practice.

It is important that the campaigners in England understand that a law granting what appears to be universal access is not a panacea and that the devil is in the detail. I recently returned from walking in Derbyshire where the main issue is large estates preventing access which sit like “black holes” in an otherwise good path network. Paths just end where the obvious historical continuation is an estate track plastered with “private” signs. If the Scottish legislation applied there would be no difference as the presence of gate lodges and other estate buildings would invoke the “curtilage of a dwelling” exception and the power of the estates would ensure it was upheld if challenged.

While universal access would be nice to have, on both sides of the border what would have more effect in practice would be an access body with powers and resources to look at path networks in detail and make changes as required.

The English path network is full of anomalies where paths go through farmyards and even gardens or take circuitous and illogical routes for historical reasons but can’t be modified even where there is an obvious better route for everyone.

Essentially English campaigners should be aware that the Scottish model is seriously flawed and should be used as a guide to how not to do it.

Hi Niall, I don’t think you have got this right. Large estates are NOT exempt from access rights in Scotland. Like other properties it is only the curtilage of the the building and the garden which is exempt from access rights and there are a number of legal cases in Scotland which have confirmed that Gloag, Snowie and Drumlean. While in those cases the landowners wanted exclusivity to a large area of ground claiming their land was part of a garden etc, the judgements did not support that and have treated the “grounds” around a property as being included in access rights with only the formal garden areas exempt. In theory of course landowners could decide to try and create enormous formal gardens but that is very expensive. Scotland’s access laws would therefore help deal with the issue you raise (A bigger issue is where landowners are trying to turn their grounds into a paying attraction). Where I would agree with you is the paths provisions in the Land Reform Act are too weak but, as you point out, so are chopped off rights of way in Derbyshire. The draft legislation we handed over to the Right to Roam in England left the paths section blank, so it could build on and improve the Rights of Way network in England

That is exactly the point. In the cases I mentioned there is a building or group of buildings at each access point around the perimeter of the estate so the track is within the individual curtilage. The estates would use their considerable resources to fight legally to retain this and as the cases you mention show, they would win. They don’t have to build enormous formal gardens, just quite small ones strategically placed across the practical access points. Exactly what has been done in Scotland at places like Caladh. While in theory under the Scottish system you could bypass the area around the dwellings and access the track further in, we know how that works in practice, a few fences and some impenetrable undergrowth, ditches etc. and job done.

Around here many of the rights of way have a farm or other buildings where the track meets the road, same applies, gates, dogs etc. yes, they are supposed to allow access or provide an alternative – report it to the LA access team, sure, that’ll work… and that is my point and what the English campaigners need to understand, without an effective enforcement mechanism built in the whole thing is a waste of time.

This post actually seems to be claiming that the Gloag judgment was some sort of a victory for access in Scotland which is an unusual point of view to say the least. Apparently because it didn’t let her close off the entire estate.

This is the judgment which ran a coach and horses though SOAC and established in case law that the extent of “privacy” you are entitled to is directly proportional to your wealth and social status. The uncontroversial reality for most of us is that the public have a perfect right to walk, drive or otherwise pass within a few metres of our front door.

Your statement that access rights in Scotland do not apply when trying to pass the gatehouses of large estates is incorrect. The Snowie court case decision confirmed that access rights applied to the two driveways and adjacent verges next to the gatehouses (East and West Lodges) which marked the entrance to Snowie’s Boquhan estate near Stirling. The West Lodge had garden ground on either side of the driveway; this did not affect access rights along the driveway. Access rights do not apply to a small area of garden ground and the formal lawns at the front and rear of the main house. Snowie initially claimed access rights did not apply to approx 70 acres of his estate, later reducing this to 40 acres. The court decided that access rights did not apply to less than 13 acres, much of which included the main house and associated buildings. A similar area of ground was excluded from access rights by the Gloag court decision. Taken together these two court cases, along with the later Drumlean court decision, support the principles embedded within the access rights contained within the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. There is nothing wrong with this legislation – whether access authorities are sufficiently effective in their responsibilities to implement this Act is an entirely different matter.

It is good that there is case law supporting in theory access over driveways. Unfortunately making effective use of this would require enforcement in thousands of individual cases all over the country, which leads to precisely what is wrong with the legislation per your last sentence – it does not sufficiently compel access authorities to implement it. This is a deficiency in the legislation which is not found in other legislation, one could speculate as to why this is.

Presumably “less than 13 acres” means more than 12. The fact that this is less than originally claimed does not make it a success in principle, it still gives them the right to exclude the public at a far greater distance than is afforded to “normal” people.

The vast majority of people cope perfectly well with the fact that the general public have a right to walk past their house and their protection against antisocial or criminal behaviour is that given in law.

While it can be agreed thatanonmylies exist within the path and roads network in Scotland, many transient access rights (along what would now frequently be defined as ancient rights of way) would have predated current maps; ie: well before any open access legislation When researching old roads in the Scottish borders for a car club a few years ago, I discovered definitive maps, but observed that most do not include all such routes. However, hidden deep within the council lists of adopted roads now avaiable for study online were a large number classed ‘D’ or ‘U’ (unclassified roads). These often ran between old agricultural buildings in remoter places. The run of the route often could not even today be spotted by enlargment of online satelite imagery.

It was reassuring that when I asked at local farms they usually freely admitted that the old “adopted” road was still there, and had never been either repossessed by the landowner, or surrendered from assigned duties under the councils ancient obligation to maintain it at Public expense. There were a few exceptions where the full road closure process was declared to have been undertaken by an estate very recently. But on the ground evidence to confirm legality of this claimed status was murky.

This remains a legal conundrum which will only be noticed perhaps accidently – as in my case – by those who have the time and incentive for real study. Landowners or their tenants today will never admit an “open route for a motor vehicle” still exists, unless prompted by someone better informed.

A whole lot requires further clarification still, despite the ‘scythe’ that cut away so many old feus and burdens in 2004/5. Of course hard pressed councils would be horrified to find that the public purse remained obliged by some ancient adoptive agreement to replace some culvert ,cutting or pack-horse bridge structure on a route no longer in much use.

Unfortunately there are no definitive maps in Scotland. Scotways claims to maintain a record of Rights of Way but only make it available to commercial users at a price, online access for the public is stated to be an aspiration for some unspecified time in the future.

I found, as part of another Council document and not indexed on their website, an OS map extract marked up by my local council with the rights of way in my immediate area each given a reference number. The majority of them are in reality on the ground obstructed or entirely obliterated.

The English system of definitive maps is not perfect either. I found a section of path in Derbyshire which has signs pointing out that the path on the OS maps is wrong and impassable and directs you to the right one, apparently OS admits this is the case but refuses to do anything until the local council corrects the relevant definitive map which they seem in no hurry to do.

Whilst common law rights of way will always have significance – we now have >21000km of Core Paths, legally protected, and mapped by the access authorities in Scotland. Our Ordnance Survey which dutifully mapped the (ridiculous) CROW Act open access areas – now refuses to map our Core Paths. An organisation based in England choosing to ignore the statutory legal position in Scotland. Shame on them.

From mine above this is probably not an England / Scotland thing just OS being bureaucratic as appears to be their way.

It would be useful to have core paths shown on OS maps as it would make obvious the stupid situations where a path apparently stops at an arbitrary LA boundary because the other authority doesn’t agree that it’s a core path, and the vast inconsistencies of provision between authorities.

When one is asked, during time of war, to “fight for YOUR country you would probably don a tin hat and carry a gun and off you go.

When someone has given their life for their country we should damn well be able to wander our hills and mountains whenever we please.

Millions died in the second world war so we could be free today. As long as you respect the countryside and remember people have to make a living from the countryside I will wander the wild country as I please.

Anyway how did the land owners of today get ” their ” land??

As far as I’m concerned it was stolen from the ancient, indigenous peoples of the country.

“Anyway how did the land owners of today get ” their ” land??

As far as I’m concerned it was stolen from the ancient, indigenous peoples of the country.”

Well some of us bought it after working for the bank for 25 years among other things.

No different from any house buyer really.

Ancient indigenous people of UK, such a thing?

Sorry but that answer is no answer at all.

The fact that you bought it from someone who sold it to you makes no difference to the fact that it is all ultimately stolen.

You say you bought it from someone. OK who did they buy it from? And who did THEY buy it from etc etc.

Eventually it goes back to a point in time where someone came along and says “this is mine now and I’ve got an army to say so”.

It’s that simple when it comes down to the nuts and bolts of it.

Everyone who buys it from that point onwards (including you) is literally just handling stolen property, and we all know what the law says about that. It says you have to relinquish it.

I don’t make laws, but I DO think they should be consistent, and so should you.

I thought Dave Morris’s paper a very good one and actually it is time that his major contribution to the creation of the Access Legislation in Scotland was more fully recognised. Give him and OBE for example. There always seem to me to be two points annent public access to countryside that should be borne in mind and Dave begins to touch on them when pointing out that much of the access needs to be close to settlements etc. We are in the midst of an environmental crisis and an important part of the solution is in getting an increasingly urbanised population to understand and relate to the natural world they are dependent on but which is obscured in the urban setting. There are excellent TV programmes etc that explain and demonstrate this but there is no substitute for the direct experience of nature for developing that attachment and that is where local access and path networks can play a important role.

The other point is that it has always seemed to me that the access legislation and right to roam are a much more fundamental piece of legislation than is generally realised. Landownership is basically right of use and right of disposal of that use by sale, renting etc and under old approaches it was a pretty exclusive set of rights allotted to private landowners. The phenomenon of emergent landuses has challenged all that. When communities assert their right to protect catchments that supply water they are asserting right of use. Equally even National Scenic Area designation assert right of use for landscape, and then along come carbon fixation etc. Basically all landuse is multiple and all landownership is multiple and the Access Legislation and right to roam is basically an assertion of the terms on which we live together and share the land and we live in.

The second half of your last sentence sums up a thread which runs through this discussion. Whatever the original intentions of the drafters, what the legislation has become is something to point at as proof in itself of adherence to a virtuous principle. Whether or not it is effective in practice doesn’t seem to matter for this purpose, as long as we can say how wonderful we are to have this legislation in place.

I like to think that at least some of the original drafters simply wanted to improve outdoor access rather than make a political statement.

The campaigners South of the border need to realise this and avoid being fobbed off with another largely meaningless bit of paper.

nteresting discussion, marred somewhat by moving goalposts, and straw men: ‘meaningless bit of paper’, in reference to radical legal and existential change in LRSA. Now, no dispute about whether we have access rights, only a question of how.

However, perhaps we could look again at SOAC? Recent on the ground developments- bye laws (LLand T) and ‘advice’ (CNPA), suggest it’s creaking somewhat. And post-Covid recreation changes, and climate change, create new conditions.

SOAC- ‘produced by decent chaps for decent chaps’- needs looked at. But unfortunately, it would be a case of naturescot ‘marking their own homework’. How to break this logjam?

There is certainly a dispute over whether we have access rights or a bit of paper saying that we do. My experience on the ground is that the situation is getting worse, not better.

There is no breaking the logjam as long as politicians and the like are happy to wave the bit of paper and boast about it. I think most of them are quite happy with the status quo, for them and the “landowners” it is working as intended.

The first step in reforming SOAC is getting acceptance that it doesn’t work. There is an opportunity for reform suggested by this article in that if we can make sure that those working for an English version understand why the Scottish one doesn’t work and avoid blindly copying it, they may come up with something better which would make the difference obvious.

Niall, sorry to hear about your experience, although a sample of one hardly makes the case.

And not sure that ‘most’ are happy with status quo,given the trashing of parts of the countryside recently, and cost of mitigating that.

I’m dubious about cross-border transfer: different culture/demography/land use pattern/legal system/etc.

But yes, agree that ‘acceptance’ that it’s not working is prerequisite. How you suggest we get there?

My experience is observation of the reality in various places over years and is experienced by everyone who tries to take access there. I can only assume that my experience of LA access teams would be the same as any other member of the public.

The reality is that “most” have no interest in walking anywhere, and believe whatever the mainstream media tells them. If they think about outdoor access at all they believe that everything is fine because we have the bit of paper.

How do we get there? I don’t know, and suspect that the underlying principle goes against the current political desire to limit mobility. I don’t think that articles like this one which start from the premise that the current Scottish situation is superior and a model for south of the border are helpful in that regard. I walk mainly in England because even the current system works better in practice and while not perfect by any means gives a better experience overall.

Perhaps it would be useful to formulate and promote an alternative without the current shortcomings. I doubt it as there would be huge resistance from the civil servants to something “not invented here” and the politicians and officials would see it as outside interference and a threat to their authority. It would be necessary to keep it out of the hands of their pet organisations that they fund who will produce yet another glossy report and / or hijack it for their own ends. That aside, what changes need to be made?

Primarily a paths based strategy. To qualify for public funding, projects would have to include specific provision for access in the form of paths, stiles, gates etc . While universal access rights are an important underlying principle the practical effect of being allowed to climb over barbed wire fences and wade through bogs is of minimal benefit. Responsible bodies required to regularly review path networks under their control with a view to improvement and expansion. A presumption against conversion of footpaths to so called “mixed use” or the provision of same.

Enforcement. Even the provisions of the current SOAC would be much better if proper enforcement had been built in. There is no point in leaving this up to local authorities if they can choose whether or not to fund it or prioritise it. Other legislation (e.g. Housing (Scotland) Act) has specific duties, timescales and penalties for inaction built in. My experience is that LAs are happy to mess you about forever at the basic customer facing level unless and until you point out that they are in breach of their legal obligations at which point it goes up the organisation like a rocket and things happen. As to the question of funding, this would be between the LAs and central government to sort out, it is part of what we elect and pay them for.

Hi Niall, I am glad you recognise universal access rights are an important underlying principle. I believe they have made a different because it gives people in Scotland who are aware of those rights the confidence to be on land in a way that is not possible in England. Hence the importance of the Right to Roam campaign. You are quite right, however, the paths in Scotland are still not good – that is partly why the draft RtR Bill we handed over at the border left the paths section blank. While England has a much better path network at present, we cannot suddenly import all the history that goes with their Right of Way system, so I would agree we need a new paths based strategy. I also agree with you that enforcement mechanisms need to be made more effecitve but it would be totally wrong to try and make SOAC, which is advisory, enforceable as you suggest. Bad behaviour by the public, as I have explained in previous posts, is already covered by the criminal law, which is enforceable. The gaps are around signs, fences, etc. The main body of the Land Reform Act does give access authorities the power to remove obstructions but the prescribed procedures for doing so are not effective and if the Access Authority fails to act, like the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority has in Balquhidder there is no remedy.

Seem to have hit a depth limit. This is a reply to Nicks of Oct 12 11:22.

What I would like to be enforceable is the Access Authority response, as otherwise as you say if they don’t feel like it they will do nothing. Effective legislation would specify the timescale for responding to a report of obstructed access, what action should be taken and what penalties would be applied to an authority failing to act in a timely manner.

I completely agree that public behaviour is covered by criminal law – in an ideal world it would be a useful side effect if the rich and powerful had to rely on the same level of law enforcement as the rest of us when subjected to antisocial behaviour rather than being able to keep the plebs a convenient distance away.

Looks like whoever you vote for the answer is no:

https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/uknews/england-is-too-different-from-scotland-to-have-right-for-roam-says-labour/ar-AA1kN8rT?cvid=c5781a11064e4273ea74cae05d4602b6&ocid=winp2fptaskbarhover&ei=6

… for the same stupid “reasons” debunked in this post.