The consultation on the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA)’s National Park Partnership Plan (NPPP) 2024-29 has been live since 26th April and closes on Wednesday. There have been few responses so far through the online platform “commonplace” (see here) despite the LLTNPA’s attempts to frame the new plan as having a pivotal role in addressing the climate and nature emergencies:

The response rate appears to be significantly lower than the number of responses to the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) NPPP consultation in 2022. That is partly because the CNPA made more efforts to engage and has better relationships with stakeholders but is also I believe a consequence of the meaningless consultation system. The Scottish Government and public authorities have conducted endless consultations on policies, strategies and so-called “plans”, most of which have ignored the concerns raised by respondents or made any difference, and people are now starting to realise that.

The LLTNPA has a particularly poor record in this respect and that is now coming home to roost. The best example is the LLTNPA’s outdoor recreation plan which was first delayed for years (see here) before an anaemic set of proposals (see here). After a large number of people and organisations had devoted considerable effort to responding the consultation (see here), the LLTNPA eventually announced it was ditching the plan but would incorporate revised proposals in the NPPP. That has not happened (see here) and the draft NPPP is devoid of meaningful content in respect of outdoor recreation (see here).

The message could not be clearer, responding to the LLTNPA’s consultations has become a pointless exercise. How else to explain that only one comment has been submitted about Balloch on Common Place despite the 55,000 or so people who have objected to the proposed Flamingo Land development there?

The LLTNPA does, however, have a statutory duty under the National Parks Act (see here) to take into account comments made on the NPPP during the consultation period. It may therefore be still worth responding, either to highlight particular local issues that need to be addressed on the online map (areas with overgrazing, industrial forestry plantations, lack of visitor infrastructure etc) or to use the survey questions to question the legitimacy of the plan or whether it is fit for purpose.

The rest of this post considers the main failings in the NPPP and I will follow that up with a further post that considers why the LLTNPA’s NPPP and plans more generally say so little.

A plan without foundations

The information contained in LLTNPA’s draft NPPP and the accompanying documentation about the current situation in the National Park could at best be described as random. This contrasts with the Cairngorms National Park Authority which in 2021 published a series of Fact Sheets to accompany every aspect of the consultation on its NPPP (see here for an example on land management).

While each main theme in the plan has sections headed “current situation” in most facts are few and far between. For example, under Enabling a Greener Economy and Sustainable Living there is just one half-fact, that the population for the National Park is projected to fall further, from 14,700 to 14,300:

Unlike the CNPA, no facts are presented about the economy (eg about wages) but instead the views of one sector of business, representing tourism, are reported as reflecting the current situation. That may or may not be true but without facts its impossible to tell.

Many of the figures and statistics that are reported in the NPPP are from bodies like Visit Scotland and are for the whole of Scotland. They may or may not reflect the position in the National Park.

While there are a handful of mentions made to research conducted in the National Park, no references or links to that research is given. For example:

“The Footprint Assessment for the National Park completed in 2022 showed that visitor travel to and from the area is our single biggest source of emissions, totalling 290,978 tCO2e per year, nearly half

of the overall footprint. The assessment’s suggested pathway to net zero includes six categories of emissions reduction targets. Visitor travel to and from the area has the largest baseline of the categories at 34%.”

This particular research is very important not just in itself but because the draft NPPP contains suggestions that the LLTNPA should curb visitor car use. It has not, however, been made available as part of the NPPP consultation and is therefore impossible to scrutinise.

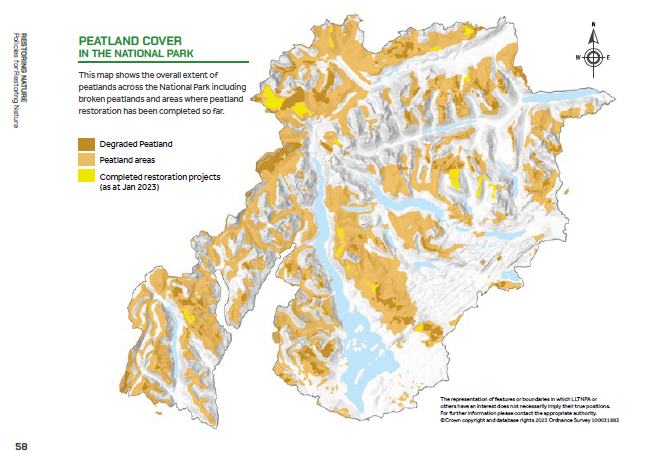

Arguably, the best factual information in the NPPP is in the maps on pages 57-59 (woodland cover, peatland and ecological status of water bodies) but no further information is then provided to explain or interpret what is going on:

It is important, for example, to understand the reasons for peatland being degraded in order to decide what to do about it: how much is natural, how much due to overgrazing, how much due to other human impacts?

A plan out of context

While the draft NPPP contains a diagram showing that it is the overriding plan for the National Plan no attempt is made to relate its content to other plans.

Most importantly, the draft NPPP is completely silent about what the 2018-23 NPPP: what was achieved; what has been learned; and what needs to change as a result. In other areas of planning – like procurement for example – the mantra is Analyse, Plan, Do, Review. What the LLTNPA has DONE over the last five years is completely missing from the plan as is any attempt to REVIEW this. There was a time when the Scottish Minister responsible for National Parks personally reviewed the NPPP each year at a public hearing but since that was discontinued there has been no accountability.

The failure goes wider than that though. There are references in the NPPP to other strategies and plans, like the Woodland and Trees Strategy (see here), which is supposed to cover the period 2019-39. So what has that achieved to date and what in that strategy now needs to be changed as a result of the LLTNPA taking the climate and nature crises more seriously? The NPPP is silent on these issues, a missed opportunity but also an indication the LLTNPA appears incapable of ensuring even its own planning documents join up.

A plan without partners

That disconnectedness extend to the LLTNPA’s relationship to its “partners”, particularly other Public Authorities. A primary purpose of National Park Partnership Plans is to ensure that everything done by other public agencies within the National Park boundaries joins up and supports its objectives.

Yet the input from public agencies to the draft NPPP (it was the same with the last plan) is almost non-existent. There is nothing to say how Forest and Land Scotland (FLS), the largest landowner in the National Park, plans to change the way it manages its land for nature or as a result of climate change (nor what it will do to support outdoor recreation). There is nothing to say what NatureScot, responsible for protected areas, plans to do to ensure they are “in favourable condition” or how it plans to manage the land it owns in the Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve. There is nothing to say what Transport Scotland plans to do to ensure train services to the National Park improve. Or what Scottish Water proposes to do at Loch Katrine and so on for a host of other agencies.

Aside from FLS, the largest and most significant gap is the lack of any input from local authorities. But then the LLTNPA has proved incapable for more than a decade of ensuring a co-ordinated approach to issues such as litter management and parking provision which are also the responsibility of local authorities The NPPP should be the mechanism that the LLTNPA uses to sort these issues out but instead they have yet again been avoided.

Instead of building other public authorities plans into the draft NPPP and using the consultation process to iron out the contradictions and conflicts, the LLTNPA is consulting those public authorities at the same stage as the wider public. In the unlikely event those authorities did come up with significant new proposals, there will be no chance for the public to comment on them.

A lack of analysis

Without factual foundations any meaningful analysis of the current situation in the National Park or what actually needs to be done is almost impossible.

Most of the sections on the “current situation” say far less about the National Park than they do about the legislative and financial framework. The resulting “analysis” makes all the right policy noises from a Scottish Government perspective without saying what needs to change:

For example, “the recognition” that high grazing levels are incompatible with climate and nature goals – which is repeated throughout the plan making it sound as though the LLTNPA has taken this to heart – is not accompanied by any factual information about deer and sheep densities across different areas nor does the LLTNPA say anything about what those numbers should be (the CNPA draft NPPP by contrast contained targets for maximum average deer densities).

The failure to analyse goes deeper. To return to the peatland map, while it does provides an indication of the areas where peat could be restored, without knowing the causes of this there is no way of telling whether the proposed solution (using government money to pay for contractors to do restoration work by machine) is sensible or will work. There is no point trying to restore peatland damaged by grazing animals unless the numbers grazing in those areas is reduced.

A plan without meaningful objectives and actions

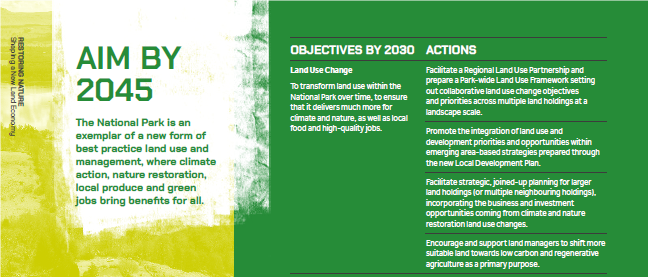

The draft NPPP includes aims for 2045 and objectives and actions for 2030, a year after the plan will have finished! Here is the example for “Shaping the new land economy”

The aim is full of fine words and phrases (exemplar, new, best practice, benefits for all) but what does it actually mean?

And what does the objective actually mean? How, for example, will FLS “Transform over time” their landholdings and what is involved in”delivering much more for climate and nature”?

As for the actions, there is not a single action that promises to change anything. The are all about facilitating partnership – the LLTNPA missed the opportunity to show it could do that while drafting the plan – promoting this and encouraging that. None of these things are “actions” and its highly questionable whether any will make any difference. In the early years of the National Park, for example, the LLTNPA tried to get estates to develop integrated land management plans – I had to appeal to the Information Commissioner to get a copy of the one for Glen Falloch – but the whole initiative was dropped without explanation. What has changed that would make such an approach work now?

A plan without resources is not a plan

Large sums of public money are still spent in the National Park each year despite austerity. These could, if used in the right way, make a considerable difference. While acknowledging the issue of rural grants, the plan fails to make any proposals about what needs to change. To quote one of the slogans at the start of the plan back to the LLTNPA, “if not now, when?”

While taking on other public authorities like FLS would require a real battle, the LLTNPA really has no excuse for failing to say what resources it needs as a National Park Authority to deliver its objectives and how it would intend to deploy them over the next five years. It should be blindingly obvious that whatever is in the NPPP, unless the LLTNPA has the appropriate resources in place they won’t be achieved. So why the silence?

The fact the draft NPPP says nothing about resources confirms my main contention, the plan is devoid of meaningful content and not worthy of a National Park. The Minister should step in and sort the LLTNPA out before they are allowed to go any further.

I recall a meeting of the NP Fish and Fisheries Forum. The Forestry were on it. They own fisheries. Someone asked the guy, “Have you got nothing to say?” He just got up and walked out of the room never to return. Looks like the rest have gone AWOL as well. They’re off backing the Nazis in Ukraine. It’s been discovered the Brits are behind NAFO/North Atlantic Fella Assoc, the NATO crowd on social media with the cartoon dog. All the death squads front on furry animals and charity. Looks like the inventor was a Pole and then a Lithuanian took it up funded by the Brits. The Rainbow Coalition and the Greens are in on it. The German Greens are full Adolf. They backed the destruction of Yugoslavia before. Did I say I got reinstated on Twitter? That was a 3 year ban on a pack of lies by the Syrian Opposition/US State Dept. I’ve been on mastodon scot and mastodon glasgow social. I was lucky to get through the first week. They’re awash with Greens and Rainbow Nazis. The people at glasgow social informed me directly….”We’re 100% Gestapo, this is you’re final warning.” They might as well raise the Swastika and call it the Nazi Park. That’s the dark side of the liberals for you.