Background

The successful re-introduction of beavers to Scotland owes very little to our public authorities and everything to the people who, whether accidentally or not, allowed beavers to enter the catchment of te River Tay. While the official trial in Knapdale floundered – the river system was too small and the catchment isolated so the beavers had nowhere to go – those on the Tay flourished and rapidly multiplied.

The news that farmers were shooting beavers in the Tay catchment and the public reaction to that then forced the Scottish Government to add them to the list of species given legal protection on 1st May 2019. At the same time, however, the Scottish Government announced – in response to pressure from farming interests – that there would be no further releases of beaver and they would be allowed to colonise new areas naturally over time.

Prevented from issuing licenses to move beavers that were allegedly causing damage within Scotland, Nature/Scot, as the public agency responsible for nature conservation, granted permission to move some to England but also started issuing licenses to kill them – 87 by the end of 2019 as revealed by the Ferret (see here).

Two years later, in November 2021, the Greens used their co-operation agreement with the Scottish Government to extract the concession that some of the beavers being culled could instead be translocated, but only under license, within Scotland. This announcement was too late to help the beavers in 2021: NatureScot later reported (see here) that in that year 120 beavers had been removed from Tayside of which 87 had been killed.

Early in 2022 there was a quick win, when some beavers were moved to the Argaty Red Kite Centre near Doune (see here). There were, however, no further releases to other sites despite Forest and Land Scotland having promised to re-introduce beavers to three new sites on its vast landholding before the end of year (see here). NatureScot claimed (see here) last month that in 2022 there had been a significant decrease in the number of beavers that had been lethally controlled (108) compared to those that had been moved (45) but once again they have England to thanks for this as only 15 of those beavers were translocated within Scotland.

This provides the context for the translocation of a single family of beavers to the Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve in January this year. Meantime the Ferret, which has helped expose what has been going on, raised questions in April about whether the beavers that are still being killed are being culled humanely (see here).

NatureScot’s beaver strategy – a recipe for conflict

Following the Scottish Government’s u-turn on translocations within Scotland, NatureScot produced a Management Framework (see here), a mitigation scheme (see here) and then in August 2022 “Scotland’s Beaver Strategy 2022-45” (see here). This, it claimed, represented “one of the most ambitious and forward-looking approaches to managing and conserving a species ever carried out in Britain”. In truth the strategy appears designed to slow the spread of beavers across Scotland as much as possible and has mired the process in ineffective bureaucracy.

The Strategy’s fundamental flaw is that it requires extensive assessment and consultation to take place before any beaver translocation can happen, while at the same time failing to provide adequate means to address the legitimate interests of landowners. The predictable consequence is that most private landowners either don’t want or are fearful of the consequences of beaver translocations into their river catchment. The first part of the problem is NatureScot’s decision to focus its attention on two or three “priority catchments” for release which has given every incentive for private landowners and the organisations that represent them to argue, whether behind the scenes or in response to each consultation, “not in my catchment”. The second is when having identified a suitable catchment it then asks landowners to come forward with possible sites and consult on these. This has played into the hands of powerful landed interests who are opposed to beavers.

The Strategy rightly identifies that “Resources, including financial, to support longer term, post-release monitoring and management are key” but fails to provide a clear description of the costs associated with beaver re-introduction and how these might be addressed long-term. There are two main issues.

The first is in respect of farming, where NatureScot’s mitigation scheme refers landowners to grants that are available under the Agri-Environment Climate Scheme. (Unfortunately there is still only one mention of beavers in the Scottish Government’s guidance on rural payments and that is as a protected species (see here)). Those payments include, for example, the creation of water or grass margins in arable fields which could help with beavers and for which farmers currently receive £495.62 per hectare per year. From a farmer’s perspective, the decision whether to apply for such payments or to apply for a license to kill beavers is likely to be primarily determined by financial rather than ecological considerations: the yield and market price of the crops they might grow on those margins, rather than how re-wilding parts of flood plains could help reduce flood risk. Until this issue is addressed, any landowner who is likely to be better off farming is likely to oppose the re-introduction of beavers to their catchment.

The second is issue concerns other people who own land by watercourses that might be colonised by beavers. Such landowners, mainly small, are entitled to “expert advice” from NatureScot but there are major limitations to the practical/financial assistance they can receive under the mitigation scheme (see here) including:

- “Use of public funds will be directed to protecting public rather than solely private interests[1] and in addition will need to demonstrate good value for money.”

- “Following the end of the agreement period there is an expectation that the responsibility for the installed mitigation will revert to the land manager.”

What this appears to mean is if a house owner’s garden backs onto a water course and beavers start burrowing under it, that’s is the owner’s problem but, in the case where there is a footpath running between the garden and water course, the owner might be entitled to help in the short-term on the grounds that protecting footpaths is in the public interest. In the medium-term, however, even those landowners ould be left with the longer of maintaining any mitigation measures put in place. This is clearly unfair and it is no wonder that local communities have raised concerns about beaver re-introductions to their area.

Having created a translocation framework that foments opposition – which may well explain Forest and Land Scotland’s failure to deliver the re-introductions they had promised – NatureScot has still has had to deliver beaver re-introductions somewhere, to show it is doing something to reduce the number of beavers that are being culled under license and to satisfy the Government Minister responsible for biodiversity. Hence, the much publicised re-introduction of beavers to the RSPB reserve at Loch Lomond.

The proposal to re-introduce of beavers to the Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve

The RSPB have long been supportive of the re-introduction to beavers in Scotland but they had also been developing plans to expand facilities and attract more visitors to Ward’s Farm, part of the National Nature Reserve at the South East corner of Loch Lomond. With beavers having been recorded on camera there back in 2019 it made sense from their perspective as conservation owners to offer their reserve as a beaver release site. .

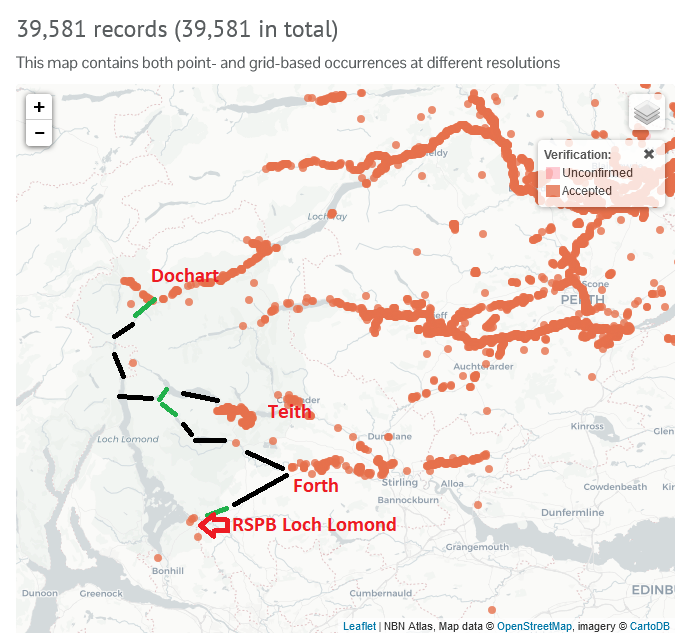

NatureScot produced a Strategic Environmental Assessment last autumn (see here) which revealed that beavers appeared to have already migrated into Loch Lomond from both north and south.

Given time, it appears beavers would have become well-established around Loch Lomond anyway. Translocating them should have been a non-event if appropriate resources had been in place to mitigate/compensate neighbouring landowners of their impacts.

When, however, NatureScot consulted on the draft SEA (see here) they batted away concerns expressed by local residents about the potential costs and the lack of plans and resources to deal with this:

Comment Response Action

| Transparency that land managers will incur costs in monitoring and dealing with beaver activity | In table 9 of the Addendum there is recognition that living alongside beavers whilst expected to bring net environmental benefit, will bring additional time requirements and costs to land and fishery managers; to managers of assets and the public agencies. | No |

| Concerns regarding the level of resourcing for mitigation. Landowners should be compensated for damage and mitigation fully funded. | Comments on levels of resourcing are outside the scope of SEA, but are relevant to the practicality of mitigation being available to address the potential negative environmental effects identified. A key tenant [sic] of Scotland’s Beaver Strategy is to support living with beavers and reducing negative impacts long-term. Actions to ensure funding needs are met are being led by NatureScot and Scottish Government. | Yes as part of Scottish Beaver Strategy implementation. (green = action required). |

Now it is possible the concerns and fears of local residents around the Loch Lomond Nature Reserve about costs were exaggerated but, if so, NatureScot provided no information to re-assure them about the time and cost that might be involved. Instead they asserted this was outwith the scope of the SEA.

NatureScot then left it to RSPB to consult on using the Aber Burn at Ward’s Farm as the release site, despite the conflicts on interest involved: the fact that NatureScot were part owners of the National Nature Reserve and that while the release of beavers could only enhance the ecological and financial value of the RSPB property (due to all those extra visitors attracted by beavers), it could have the opposite effect on neighbouring properties left to manage the consequences of the re-introduction. Throughout all of this the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) was notable for its absence.

NatureScot’s decision and local communities

NatureScot granted the RSPB a license to release beavers on the Aber Burn in October 2022 soon after they had applied for this. The terms and wording of the decision (see here) is mired in bureaucratic rules and speak, mostly cut and pasted from the decision to release beavers at Argaty, and designed to prevent any legal challenge. The content, however, illustrates how the current framework for translocating, managing and mitigating the impact of beavers is unfit for purpose.

In Section 3.2.3 on Stakeholder consultation NatureScot reported that although “not all issues were resolved to everyone’s satisfaction NatureScot consider the consultation was proportionate and has been effective in identifying the range of potential issues that may arise from beaver presence”. The problem from a local perspective is there is little consolation in NatureScot identifying the issues if local residents are still left with picking up the tab for addressing them:

“Further engagement will, however, be required to work with local communities and stakeholders to discuss potential mitigation of the specific concerns of those likely to be affected. NatureScot expect to have a role in advising on mitigation and would aim to work with others locally to develop an effective monitoring and management plan that seeks to minimise any negative beaver impacts and maximising the benefits and opportunities arising from beaver restoration.”

No promise of resources here! NatureScot’s response to the concerns raised by local farmers dumps almost all financial responsibility onto them:

“The risk of serious agricultural damage is regarded as low as the land is not of the same capability (is not Prime Agricultural Land) as where the beavers are being moved from. However, we do recognise that there is the potential for beavers to cause localised flooding necessitating beaver mitigation or potentially the removal of dams under protected species licenses.”

That is no help farmers on less favoured land who also need to earn a living: if beavers are causing problems, the onus is left with farmers to demonstrate how that and then go through the hassle and cost of trying to obtain a license to remove a dam.

Other concerns raised by the local community, about the impact of beavers on private water supplies, heritage trees or trees that people have planted in their gardens, were similarly batted away along with the costs of managing this:

“It is appreciated that having beavers resident will likely bring additional management and time considerations for land managers [this includes home owners!], but these would likely have occurred in due course following a natural colonisation by beavers in the catchment.”

The decision at Loch Lomond confirms the fundamental failing of NatureScot’s Beaver Strategy, it does not provide any means or way forward to support people with managing the costs of living with beavers. This is not all NatureScot’s fault, they simply don’t have the budget to mitigate the costs. But instead of calling on the Scottish Government to fund this, which they could do by re-directing some of the large sums of money that wasted on agriculture and forestry into beaver mitigation (e.g muirburn payments and plastic tree tubes), NatureScot have developed systems designed to shift the responsibility for costs onto “small people”. It is no wonder they are so unpopular in many rural communities.

NatureScot’s decision and natural processes

“Monitoring and mitigation is proposed to be required secured to ensure the conservation objectives of the following interests within the Natura [EU Protected] sites in the catchment:

- Atlantic salmon

- Brook and River Lamprey

- Otter

- Western Acidic Oak woodland and

- Capercaillie“

What a gem! Capercaillie have been extinct in the Loch Lomond area for some time but because NatureScot has failed to review the Loch Lomond islands Special Protection Area it still needs to monitor the impact of beavers on these non-existent birds!

While also committing to monitoring the impact of beavers on otters, the decision making process failed to consider the impact of otter on beaver (which are now also protected although no Special Area of Conservation has been created to assist with this). A beaver family with five kits were released on 27th January but by 16th February two of the kits had been predated by otter (see here). That is nature at work, all is interconnected and one protected species affects another. This was arguably a better outcome than the young beavers remaining on the Tay and being shot but the decision making process made no allowance for introducing another family if all five kits had been killed.

As another example of species conflict I have been informed (but have not verified) that a SEPA ecologist ordered these trees to be removed as they were preventing the SAC Atlantic Salmon from going up the burn to spawn!

The fundamental issue, however, concerns how NatureScot’s decision making process focuses on the release site for beavers. While recognising that beavers spread through and over catchments, NatureScot’s primary concern in making is whether there will be conflict at the actual release site. Where landowners can be found who support the re-introduction of beavers and who are prepared to ignore the concerns of their neighbours, as at Argaty and RSPB Loch Lomond, the decision is a foregone conclusion.

What has happened at Loch Lomond exposes this approach to release sites as a farce. By the end of May the RSPB were reporting that (see here) that few beavers had been caught on camera in the reserve and the remaining beavers were “exploring their wider home”: “We have even had reports of signs almost 10km away from the original release site”.

While scientists believe that marshy places like the RSPB reserve provides good habitat for beavers, whether beavers think so or stay there is another matter. NatureScot had produced no management plan for responding to the potential consequences of beaver dispersal from RSPB Loch Lomond before issuing its decision.

Earlier this week I was up at Mill Dam, above Dunkeld, in the Tay catchment – my third visit. There is plentiful beaver activity all round the loch, including the marshy area dotted with trees to the north, not that dissimilar to RSPB Loch Lomond and wondrous to behold. But what really struck me in terms of NatureScot’s focus on suitable release sites is how almost any burn (see above) will do, so long as there is some cover and trees nearby. Beavers create their own habitat and there are literally hundreds of places across Scotland where they could be released..

This illustrates two key points about the translocation programme for beavers in Scotland. The focus and massive bureaucracy surrounding release sites is a diversion from the real issues. Given the chance beavers will move on, multiply and spread rapidly often in ways we can’t yet predict. That is actually a very good thing for both nature and humans, not least because the way beavers engineer waterways will help with flood prevention.

However, unless the Scottish Government properly recognises the legitimate concerns and costs incurred by those living closest to beavers and provide compensation for this, the whole translocatin process will remain a recipe conflict. While some conservation landowners, who like the RSPB are likely to benefit from beavers and can bear the costs themselves, may be happy to have beavers on their land, not many are likely to be prepared to upset their neighbours. The beaver strategy is therefore hardly “one of the most ambitious and forward-looking approaches to managing and conserving a species carried out in Britain” as NatureScot has claimed. Its consequences are predictable, lots of pain for little gain.

Beaver translocation and the role of National Parks

The LLTNPA’s draft National Park Partnership Plan, currently out to consultation, contains just one reference to beavers despite its supposed focus on restoring nature. Under the actions for ecosystems the plan states the LLTNPA will:

“Support the return of the beaver to the Park’s freshwater bodies.”

It appears that instead of taking a lead and helping to address the issues identified in this post, the LLTNPA would prefer to sit back and let NatureScot take the flak!

The position of the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) on beavers is far more complex. On the plus side, in June 2022 their Board put the LLTNPA to shame and agreed (see here) to take a lead on beaver translocations in the National Park taking over responsibility from NatureScot. This followed the publication of a report commissioned by the CNPA into the potential for beavers from the Tay to colonise other river catchments in the National Park naturally (see here) and previous work that had identified the Loch Insh and Dinnet Nature Nature Reserves as suitable locations for beaver. (By contrast the LLTNPA has never done any work on beavers and kept quiet about their presence in the National Park).

On the downside, however, the CNPA accepted the constraints of NatureScot’s beaver strategy and its identification of priority catchments and agreed to focus their attention the River Spey. While this the Spey catchment includes much more deciduous tree cover close to water courses than the Don and the Dee and more conservation owners, particularly the members of Cairngorms Connect, the CNPA’s report also stated that the “overlap between beaver habitat and agricultural land use” is much higher than the Dee and the Don. Without any funds to mitigate the impact on farmers, this is likely to generate new conflict.

The decision, however, also played into the hands of landowners along the Dee who don’t want beavers out of fears about the potential impacts on salmon fishing. Both Scottish Land and Estates, which generally represents traditional sporting interest, and the River Dee Trust, whose chair, Sandy Bremner, is the new Convener of the CNPA, were represented on the Cairngorms Beaver sub-group. Research shows those fears are generally unwarranted – beavers are good for fish – and could be mitigated, as work by the WWF in Canada (see here) has shown. Sadly WWF’s President, King Charles, who fishes on the Dee at Balmoral has remained silent instead of showing a lead to other landowners.

The outcome of all of this is likely to significant delays before beavers are released onto Speyside – will the RSPB really want to take more flak from neighbouring farmers? – and it may be years before beavers are released or get to Deeside by natural means. If National Parks cannot respond to the nature crisis by restoring nature across their areas and drive forward new approaches to conservation – including the need to re-design agricultural and forestry grant schemes to compensate those who may be affected by beavers – what are they for?

On Nature. Scot’s report. If the beaver population is expanding at 30%p.a. then in three years time the population will be double what it it is today, or in six years it will have quadrupled! At the same time will the numbers killed be in the same proportion? I would suggest that it will probably be a lot more. There has to be a limit for a sustainable population, so what happens to the rest? By the time all these consultations are finished and decisions taken/ administered what will the beaver population numbers? Organisations will not move as quickly as the beavers breed.

Excellent article.

Red Alert! To all beavers, your best policy is to stay away from this lot as far as you can.

Good reading when you can’t sleep at night. I learnt a lot, very interesting.