The Scottish Government’s request for “ideas” about a new National Park in Scotland (see here) closes today. So far, 93 ideas have been registered (see here) among which I can find almost no mention of the destructive impacts of overgrazing by red deer on the natural environment. Yet if the Scottish Government wants National Parks to help restore nature and turn the land into a net store for carbon, they just need to do two simple things: reduce deer numbers (probably to c2 per square kilometre) and end intensive grouse moor management (which is registered as an idea on the consultation page). This post considers the deer issue in the light of a recent visit to Glen Strathfarrar.

I had last visited the glen in August 2011 and one of my memories was of a single very tame red deer grazing in front of a house. This May – a different time of year of course and before the main flush of vegetation on the hill – red deer were everywhere.

Indeed, there cannot be a better place in Scotland to observe the physiological changes that deer go through at this time of year. My partner decided to see how close she could get, only for an estate worker to shout from their vehicle that these were wild red deer and if she wanted to photograph them she should go to a deer farm. We were already in one!

All along the glen we had seen the remains of heaps of straw put out to help the large numbers of deer survive the winter. Down near the confluence of the All Mhuillidh and the River Farrar I counted six, a dozen metres apart. This feeding is not a casual operation but systematic.

It is little wonder the red deer are so tame. They perceive humans as a source of food rather than as a predator, farmers not hunters.

But unlike farm animals when the time has come they still do have a chance to escape. No doubt they have learned the best means of survival at different times of year.

Glen Strathfarrar is quite unusual in combining elements of wild glen and more fertile strath, its geography encapsulated in its name. There are significant areas of grassland by the river, once used to graze sheep and cattle, but which are now without the competition very attractive to red deer (and campers!). Maybe because of its topography and ecology, Glen Strathfarrar is capable of supporting higher numbers of red deer than elsewhere?

The evidence on the ground

Cycling up Glen Strathfarrar one could not help be struck by the magnificence of the woodland……….

…………..and individual old trees.

…………..and individual old trees.

But on closer look, except where fragments are protected by deer fencing, almost all of what was once a forest is dying

There were some exceptions:

Why, I wondered, have deer not been drawn to this source of food? The answer still eludes me.

And on the bank of the Allt Mhuillidh, 15m from the straw pictured above, a patch of prolific regeneration………….

………..opposite some very overgrazed alder and multiple deer tracks:

This I find easier to explain. Being adjacent to a large area of grassland and feeding area, no deer will bother to stop to graze the birch as long as other food is available so close by. But when times are tougher, after it has snowed for example, this changes. As soon as the birch, like the alder, emerges from above the surrounding vegetation or snow its likely to get browsed. Hence the state of the hillside above.

Along much of Glen Strathfarrar there are isolated birch trees, a source of seed, but when you look more closely most are growing out of crags or other inaccessible places.

That feeding doesn’t stop the browsing pressure is illustrated by this photo. There was no regeneration around the alder, which had been browsed to head height, and the old pine trees behind would be similarly isolated if it was not for the deer fence.

The Braulen Estate, which covers most of the land featured in these photos, understands all this of course, hence why all the way along the road it has planted trees in their own enclosures.

Deer management and nature conservation in Glen Strathfarrar

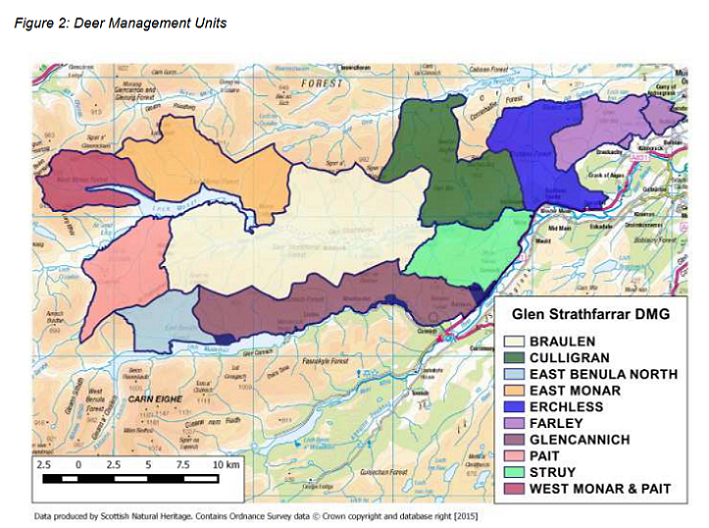

After my visit, I compared what I had seen to the written information available on the Glen Strathfarrar Deer Management Group (DMG) (see here) and NatureScot sitelink websites.

Reading the last Deer Management Plan (2016-21) for Glen Strathfarrar (see here) there was a commitment that the:

“Final Plan and Minutes of Meetings will be made publically available and published on DMG Website“.

The last information I could find was for the 2019 AGM, but that is not unusual. After an initial burst of transparency, how deer are being mis-managed is more secretive than ever.

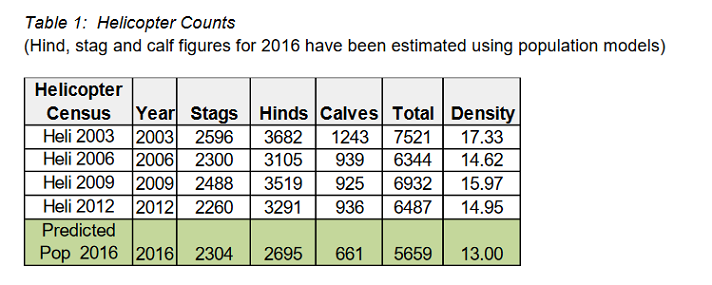

This is what the plan says about the deer population:

“Using a combination of known cull data since 2012, population modelling predicts a current population of around 5659 deer (13.0 deer per km2). A number of properties have agreed to meeting specific target densities for hinds for conservation purposes. Incorporating these densities in to the figures (the “desired” population of hinds of 3267 and an overall density of 14.4 deer km2), gives a figure which is higher than current predicted densities – meaning that the population is broadly currently in keeping with all current conservation requirements.”

Simply put, this means that actual density of red deer of 13 per square kilometre was, in 2016, less than the target agreed for conservation purposes (14.4 deer per square kilometre). No need to do anything therefore. It appears unlikely that that will have changed significantly.

The important point here is that the Deer Working Group in their report to the Scottish Government (see here) recommended a maximum deer density of ten per square kilometre. In fact we know from evidence at Glen Feshie and Mar Lodge that native woodland generally does not regenerate until deer are reduced to 2 per square kilometre (see here) so ten would still be far too high to enable the Caledonian Forest fragments in Glen Strathfarrar to recover without fencing.

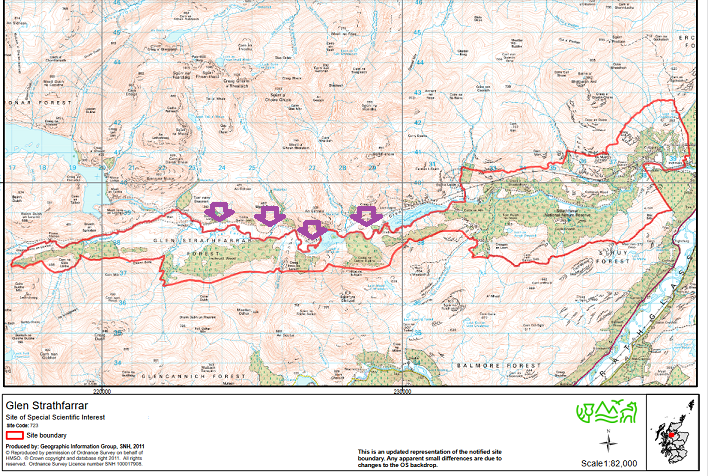

The shocking thing is these targets for deer numbers have been agreed by NatureScot, the body that oversees deer management in Scotland and is also responsible for the condition of the Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and the Special Area of Conservation.

The first objective of the Site Management Statement for the SSSI (last reviewed in 2011, another scandal) states (see here):

“1. To maintain the extent and improve the condition of the pinewood and important

upland habitats by, for example:

• managing the herbivore impacts (mainly deer)

• sensitive use of ATVs to avoid damage to ground vegetation”

It also states:

“the native pinewood habitat was considered to be in unfavourable condition due to the scarcity of tree regeneration and imbalanced age structure, particularly towards the west of the site. Browsing by herbivores is suppressing regeneration outside exclosures and, with trampling, is also affecting the condition of wet and dry heaths.”

The Site Management Statement refers to diversionary feeding – the idea that if you try and treat red deer like farm animals they will leave the trees alone:

There has also been some diversionary feeding of deer to influence the time deer spend in the woodland and hence the level of browsing on tree regeneration.”

There is no mention of how the success of this might be judged but from the evidence of what I saw, absolutely nothing has improved since 2011.

No doubt the rich grass swards in Glen Strathfarrar combined with feeding could in theory help keep red deer away from woodland some of the time, if numbers were low enough. But instead the diversionary feeding appears to be being used to maintain red deer numbers at artificially high levels with dire consequences for both woodland and the welfare of red deer: the 2019 DMG AGM minutes “noted that there were a lot of hinds without calves”, a common consequence of poor nutrition.

Could a National Park make a difference?

There is a long history of conservation failures in Glen Strathfarrar. The key points are:

- the lower part of the glen was once a National Nature Reserve, a place where nature was supposed to come first, but de-designated in 2006 like many other NNRs on sporting estates because of a failure to persuade the private landowners to agree voluntarily to conservation objectives; and

- statutory conservation measures have been similarly ineffective, with NatureScot being unwilling to use its statutory powers to control deer numbers even to protect designated sites in the glen and sanctioning – see map above – artificial feeding that has boosted deer numbers just outside the SSSI.

None of this, of course, means that had NatureScot been prepared to stand up to sporting estates and use the powers available to it – their failure to do this is not the fault of frontline staff – the current state of the natural environment in Glen Strathfarrar might not be far better than it is.

But the current system, with specific areas designated to protect what survives rather than what could be and individual private landowners with different interests (the 2019 AGM minutes reveal that the four estates covering the SSSI couldn’t even agree to apply for a £10k grant to look at the state of the woodland within it!) clearly isn’t working.

We need to think much bigger if we are going to tackle the climate and nature emergencies and protect what should be some of our finest landscapes. And that is where a National Park could come in, it could offer a new vision and a new means of tackling the issues:

- a park that covered the whole of the area from Glen Shiel in the south to Strath Carron and Strath Bran in the north and would include Glen Affric, Glen Cannich and Strathfarrar;

- a park that was focussed on the protection of nature and whose primary mission was to keep deer numbers at 2 per kilometre or less to meet that end;

- a park that had the power to force private landowners to co-operate or to buy their land in the public interest;

- a park that enabled Trees for Life to realise their admirable vision of a restored forest around Glen Affric, but without any need to plant trees and protect them with fences;

- a park that secured what is arguably the most important area of wild land in Scotland;

- a park that unlike our existing National Parks would exclude settlements but guaranteed jobs and housing to the estate staff living within it.

In my first post on the Scottish Government’s National Parks consultation I referred to Ron Greer’s idea of a Monadhliath wildlife refugium (see here). Arguably, the main disadvantage with that proposal was that the Monadhliath inspires and is probably capable of inspiring relatively few people. By contrast Glen Affric is widely regarded as one of Scotland’s finest landscapes and with a bit more protection, other glens in the area like Strathfarrar could be too. Why not build on that and create Scotland’s first National Park dedicated to conservation, to reversing the decline in nature and freeing up its potential to capture carbon?

Such a National Park would not prevent the Scottish Government creating national parks for other purposes but it would form a declaration of intent when it comes to tackling the unnaturally high numbers of red deer maintained by many sporting estates.

Nick , the disjointed approach to how of the Highland Environment is conserved despite regulation and designation has a lot to do with the explosion for deer numbers as you suggest.

For a cross reference. We came back to live in this region 20 years ago. At the time it was quite common to see herds of upwards of 20 wild deer foraging across the peat bogs and rock outcrop SSSI that surrounds us. Sheep grazed to the door…One first thing we did was to erect a deer fence to enclose around 1.5 acres around the house and outbuildings. Today we live in a young woodland. yes, we have imported trees from elsewhere, and have allowed natural regeneration of seedlings that emerge. But the fact that nothing is grazed has allowed the native trees and scrub “dormant” within this patch to re-establish itself.

By 2010 thanks to an active plan, and enthusiastic sponsorship, the number of wild deer had been right culled back. It became unusual to see groups greater than half a dozen anywhere around here. Through this past winter a neighbouring property has employed a rock pecker and transport machinery to create hill tracks leading up through native woodland to form stock feeding areas accessible by ATV (for sheep apparently). The noise of this activity,ongoing for weeks just a mile away, has displaced the native deer from longstanding shelter among those old growth trees. It is not uncommon now to find 9 -12 often rather scrawny beasts grazing our field. The previously enthusiastic local culling teams no longer receive central sponsorship. Instead they charge 3 and 4 figure sums to take guests to “find” the majestic wild deer. ( easy money ) In season, the select few might pay a huge sum to be allowed to shoot some. ) Meanwhile our small enclosed patch returns to become native woodland again. Predictably, I am unlikely to live long enough to see this grow to full maturity.

My first job as a teenager was with the Red Deer Commission in 1984. Even then the biggest problem was getting estates to reduce deer numbers. Few of the estates will change their ways without properly enforced ScotGov legislation.

Perhaps you are right and Feshie’s approach is what should be aimed for. Sometimes I wonder. A few weeks ago I walked up Coire Garbhalach to see if I could find any purple saxifrage in flower. My approach to the Coire’s entrance was across the ground half a kilometre East of the river travelling Between the Allt Fearnagan and the Allt Core Garbhalach. On most of this approximately square kilometre of ground there is very little regeneration despite one might have thought proximity of seed source. Does the ground suffer from a lack of disturbance. Might elimination of deer sometimes go too far?

There was a P and J article last week about control of hill cattle. Beasts were tagged with GPS trackers and were allowed to range free except that areas defined by a virtual electric fence were protected from grazing. Cattle straying into exclusion zones received a discouraging small shock. Otherwise the cattles’ activities were considered beneficial.

Might not such means of control work for a deer population. Expensive, definitely a challenge but might it not eliminate perhaps even more expensive, wildlife damaging fencing, allow extensive monitoring and deliver clear data with which to aid healing of the natural world.

Thanks for mentioning the National Wildlife Refugium concept once more. The suggested site of the whole of the greater Monadh Liath is one long considered not only by myself in relation to the 2016 article on these pages, but over 30 years by my colleague Derek Pretswell and myself in respect of our New Caledonia Project. We took into account the various bioclimatic, geobotanical and topographical features that gave us the best chance of the maximum habitat diversity/mosaic potential within the overall boreo-Arctic framework the massif presented, second only to the Cairngorm plateau itself.

The very characteristic of ”was that the Monadh Liath inspires and is probably capable of inspiring relatively few people’ as you point to as a disadvantage is actually one of its greatest assets in terms of the aims of creating wild land within its easily defined borders. The Refugium concept is the antithesis of creating the people pressures that result in the demand for more visitor infrastructure, urbanization and industrialization that has proved the curse of the existing so-called national parks and of course we have the example of the Craig Meagaidh nature reserve to inspire us of what can be obtained in habitat restoration. The core is in place.

An excellent thought provoking blog. My concerns are:

– NatureScot is ‘asleep at the wheel’. As you say, it’s not the frontline staff to blame but in my view poor and misguided leadership. To start with the Board needs major changes to get rid of the people that just seem to rotate from one Scottish Government posting to another – e.g. the Chair.

– Formation of a National Park in the area might help somewhat, but we don’t have good practice examples in either of our existing National Parks. The final draft of the Cairngorms Partnership Plan 2022-27 has apparently been published, reportedly taking account of the results of the consultation process, however as yet I cannot find the new draft anywhere on the CNPA website! I am concerned that issues on matters like deer management which were not strong enough in the consultation draft will have been watered down by the gamekeepers and hunting estates heavy lobbying.

Excellent article. Your attention to detail and careful observation are commendable.

I can’t help thinking that if the road up Glenstrathfarrar was open to general use some aspects of this bad practice would be exposed. It was paid for from the public purse yet deference to estates shows no sign of abating.