As usual, the latest edition of Earth Heritage (see here) has some excellent articles about Scotland but I was particularly interested to read “Reflections from a Geoheritage Sabbatical in Scotland: The View from America”:

“Scotland was a natural choice for a geoheritage sabbatical for several reasons: spectacular and

diverse geology; the importance of Scottish scientists and Scottish sites in the history of geology; the

presence of modern scholars who are leaders in the geodiversity, geoheritage, and geoconservation

fields; and a level of governmental buy-in to the significance of geodiversity and Geoheritage most

notably with Ministerial support for Scotland’s Geodiversity Charter.”

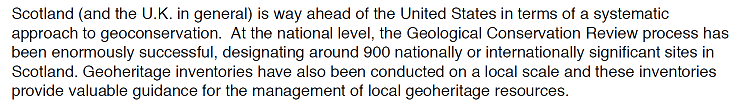

Geological conservation in Scotland in some ways comes out well compared to the US

(As an aside, the early history of geoconservation in Britain is covered in another interesting article in the same edition of Earth Heritage about William MacFadyen, the first Chief Geologist of the Nature Conservancy, which was created by the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. He oversaw the process of selecting hundreds of geological sites as “Areas of Special Scientific Interest” which later provided the foundations for the Geological Conservation Review process)

But the author, Brennan Jordan, then goes on to compare the situation on the ground, with a particular focus on National Parks:

“The greatest strength that the U.S. has in geoconservation is an enormous amount of publicly

owned land. The U.S. National Park system is frequently highlighted in international geoheritage

discussions, but as important are public lands administered by the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau

of Land Management and State Park systems. Significant geoheritage is found in all of these

lands and Government ownership provides not only an avenue for conservation, but also a natural

source of ongoing governmental funding for the provisioning of geoheritage interpretation, including

visitor centres, displays, panels, and interpretive staff. The result is that the quality of interpretation

available at U.S. National Parks is generally of a very high standard. The absence of such funding

in Scotland means that geoheritage interpretation is supported by a mixture of lottery funding, nonprofit organizations and private partnerships, with contributions from Local Authorities, government, agencies such as NatureScot, and with other valuable assistance from bodies like the British Geological Survey.” [My underlining]

“National Parks in Scotland are very different from their American counterparts, consisting mostly of

private land, though the laudable Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 (Scottish Outdoor Access Code)

assures public access to most points of interest. The two national parks, Cairngorms and Loch

Lomond & The Trossachs, both encompass considerable geoheritage resources. However, the lack

of a central funding mechanism means that interpretation resources are quite limited. The Balmaha

visitor centre in Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, provides some interpretation focused

on the nearby Highland Boundary Fault. The VisitScotland iCentre at Aberfoyle represents another

potential opportunity to provide geoheritage interpretation, but none is present. The geoheritage

community could continue to engage national park authorities and other local stakeholders to

maximize opportunities to promote geoheritage in both parks.”

This concurs with my experience. The geological display at the Balmaha Visitor Centre by the Highland Boundary Fault is a missed opportunity. It neither encourages the thousands of people who walk up Conic Hill each year to take a close look at what can be seen on the ground nor to interpret what they can see from the summit, one of the best geological viewpoints in the whole of Scotland. There is an excellent walking guide to the Highland Boundary Fault by the Geological Society of Glasgow (see here) but last time I went into the Visitor Centre it was not available. The Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority website now has a geology page (see here) with a link to this guide, one to the Callander area (funded by whole host of organisations, reinforcing Brennan Jordan’s point about a lack of proper funding) and a short video about glaciation, dumbed down in my view. But that’s it, three links for the whole of the National Park.

The Aberfoyle Visitor Centre, identified by Brennan Jordan, is far from the only missed opportunity. The suggestion from the local community that a new visitor centre could be developed at Tyndrum as part of the Cononish goldmine development was never pursued by the LLTNPA. Along with that they lost the chance to tell the geological and human history of the nearby lead mines.

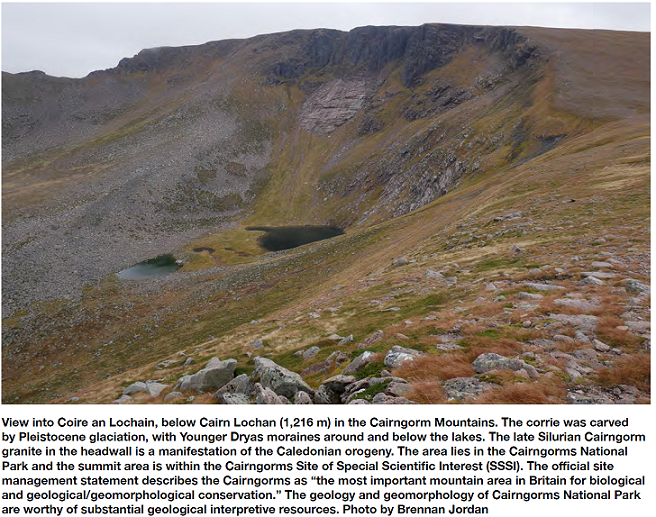

It’s the same in the Cairngorms National Park Authority and there appears even less on the CNPA website (see here for one example). The Northern Corries are, as Brennan Jordan points out, an outstanding place for mountain landforms and deserve “substantive geological interpretative resources”.

Glen More provides the only easy access point to the Cairngorm mountains and is as a consequence the biggest visitor honeypot in the National Park. Yet most visitors come and go with little idea of what they are missing. Implicit in Brennan Jordan’s piece is that Forestry and Land Scotland, who own most of the land in Glen More, compare unfavourably with the US Forest Service.

Seventeen years after their creation our two National Park Authorities are doing little fulfil their statutory aim “to promote understanding and enjoyment (including enjoyment in the form of recreation) of the special qualities of the(ir) area(s) by the public” when it comes to geological conservation. Brennan Jordan helps explain why this is the case, not just for geology but for all forms of conservation. The failures are partly due to private land ownership but, when it comes to interpretation, the problem is lack of proper public funding. The United States, that bastion of the free market, actually funds some of its public services better than we do in Scotland.

We have dozens of geological experts and hundreds of geological enthusiasts who could share their knowledge about our National Parks but they get almost no support to do so. While investment in interpretative facilities requires capital investment, a lot could be done with existing resources if there was the will. For example, the LLTNPA has the largest Ranger Service in Scotland. But they are forced to spend each winter planning for the next season of the camping byelaws rather than using their skills to develop interpretative materials for the dozens of interesting geological sites in the National Park.

Instead of treating visitors as a commodity to be managed and exploited, our National Park Authorities should, as was originally intended, be fostering informed enjoyment of the countryside. Interpretation of Scotland’s fantastic geology and landforms, which are far easier to see than our wildlife which comes and goes, should – excuse the pun – provide the bedrock for such work.

Excellent article Nick, lots of positives here, and the case must be pushed. But I fear that the relatively small sums required will not be found. Imagine if just some of the millions that had been and are still going to be “invested” in the white elephant funicular could be diverted to such interpretation, ranger services and outdoor education. I suppose we could push for geological interpretation to be added to the supposed Cairngorms masterplan, or whatever it is called.

Great article, Nick. Having some geological training, I appreciate the fascinating geology Scotland has to offer. Unfortunately Visit Scotland and our National Parks seem to ignore this great heritage subject, which is a missed opportunity to broaden the appeal of Scotland to visitors, far less educate our own population on what is under our feet. However, given these organisations struggle to get their minds round nature conservation, rewilding biodiversity etc. its not surprising.

The North West Highlands Geopark points the way forward, but will our National Parks and Visit Scotland waken up? It would be good to get a comment from at least one of these organisations on this article – because they do read them!

Interesting article Nick, and yes generally geoconservation is less commonly promoted than biological conservation in Scotland, regardless of National Park status. But it must be noted that both the history and style of interpretation in the USA is quite different from what you get generally in the UK, (as is the history of National Parks as you describe). It tends to be more didactic, lengthy and detailed to we have developed here, despite the thinking and development of more immersive and experiential interpretation by the likes of john Ververka and Sam Ham.