I was pleased to get this letter on Scottish Power’s plans to cover land around their windfarms with solar panels into the Herald the weekend before last . While our two National Parks may have no windfarms within their boundaries, the broader issue, the impact of renewable energy developments on the carbon held in soils, is one that affects both.

I was pleased to get this letter on Scottish Power’s plans to cover land around their windfarms with solar panels into the Herald the weekend before last . While our two National Parks may have no windfarms within their boundaries, the broader issue, the impact of renewable energy developments on the carbon held in soils, is one that affects both.

While estimates vary, the top one metre of the world’s soils contains more carbon than all the world’s atmosphere and vegetation combined. While trees are a very important means of developing soils and thus absorbing carbon, soils contain far more carbon than forests. And of all soils, peat – both in the tropics and in temperate zones – is by far the most important, holding perhaps six times the amount of carbon as poorer soils. It accounts for half of all carbon contained in soils. The message is that in terms of tackling the climate emergency, we destroy soils, and peat in particular, at our peril.

The impact of windfarms of carbon in soils

The Renewable Energy industry, which is mostly driven by profit rather than concern for the environment, has been responsible for destroying significant quantities of peat and releasing it in the atmosphere. The peat in the photo above may not have been the deepest – you can see the horizons left of centre – but significant quantities have been broken up during the process of constructing roads and laydown areas. The subsequent retention of the roads – maybe now locations for solar panels? – means that significant areas of the hillside are now prevented from absorbing further carbon from the atmosphere in future. They also help drain the hillsides, reducing peat accumulation on the land that remains.

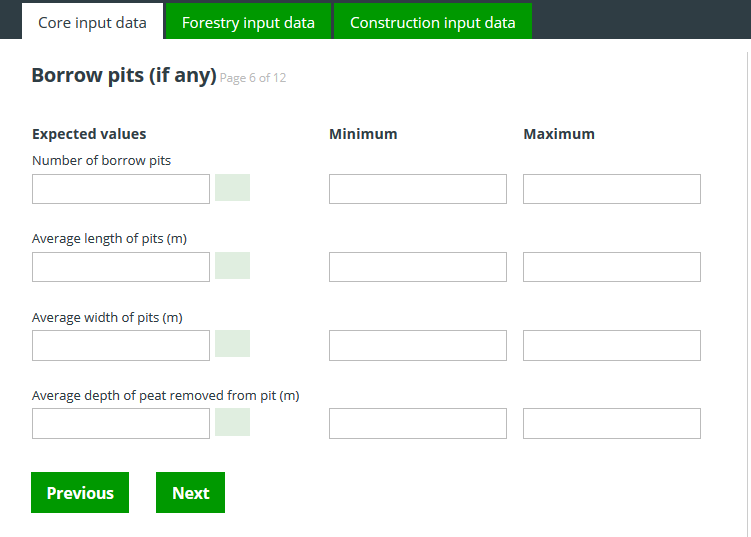

Thankfully, after a lot of pressure and lobbying, the Scottish Government commissioned Aberdeen University to develop an online carbon calculator for windfarms (see here) and a year ago it started to be used to help determine all windfarm planning applications (see here). Professor Jo Smith, who led the research, has gone on record as saying that poorly sited windfarms can actually release more carbon than they save (see here) – and that is without considering the other environmental impacts.

The net benefits of renewable energy developments in terms of carbon therefore depends not just on the size of the construction roads and borrow pits and the type of soils they cross but also on the extent to which they are restored.

The quality of the restoration is a further crucial factor in this.

Wind turbines generate large amounts of energy compared to either run of river hydro schemes – one turbine would produce more energy than all seven proposed hydro schemes in Glen Etive – or solar panels. So, despite their impacts on soils, the science says most windfarms still have a net benefit if considered in terms of carbon alone.

What we now need to do is ensure that similar carbon calculations are applied in determining the potential benefit of ALL run of river hydro developments and solar panel farms in the countryside AS WELL AS THEIR OTHER IMPACTS.

The impact of run of river hydro developments on carbon in soils

The carbon ratio for run of river hydro schemes is likely to be worse than for windfarms because they produce relatively little power and tend to require extensive new construction roads. This is well illustrated by the Ben Glas hydro in Glen Falloch which sits above the Eagle Falls. Its 1.6 Mega watts which is bigger than most schemes.

How much carbon has been released from these soils as a result of the construction work?

The net carbon impact of this hydro was never assessed in either the original planning application (approved by the Scottish Government back in 2009) or the subsequent planning application to retain a further 1100m of permanent road approved by the LLTNPA in 2015 (approx another two km of road was “upgraded)”. Both planning consents, however, set conditions requiring the developer to avoid areas of deep peat where possible – showing the Park and Government were aware of the potential issues even if they didn’t want to look too closely.

Unfortunately, the evidence from the construction of this scheme shows lots of peat was disturbed.

Moreover, while the planning report did identify the adverse impact the road could have on peat by draining the land around it., the evidence from my visit in September is this is exactly what is happening (see here)

The amount of carbon that appears to have been released from soils by the construction of the Ben hydro scheme appears, even to the unexpert eye, to have been considerable – we are talking of three kilometres of road and pipeline destruction. Then there is all the carbon that was consumed in constructing it (the plastic pipes, the concrete, the fossils fuels used to power the diggers etc). My strong suspicion is that at the end of day the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere by the construction of the Ben Glas hydro scheme may well be more than is ever saved by the electricity it generates.

Its carbon balance sheet will also depend on how long it operates. If destroyed, like some of the other Falloch Schemes (see here) it would certainly be transformed from being a potential solution to the climate emergency to being part of the problem.

Peatbogs are important not just for the carbon they hold but also for holding back water. When I visited the Ben Glas Hydro in September, after the great rain storm on 4th August which did considerable damage to the land (see here) and the hydro schemes (see also here) in Glen Falloch, I was stunned to spot this sign just by the Ben Glas hydro intake (featured in the photo above):

This raises the question of why, if the peat bog here is so important, did anyone ever consider that the construction of a hydro was a sensible use of the land? It adds weight to the suspicion that more carbon will have been released by the construction of this scheme than was ever saved.

Hey ho though, what does any of this matter so long as the landowners are being paid? First they are paid to destroy peat through construction of these schemes and then paid again to restore the damaged peat hags on the ground above? And if you want to know why those peat hags have been damaged, err well, commonly its due to the number of deer which landowners have allowed to increase incrementally over the last 70 years………….it would be hard to make up!

To rub even more salt into the wound, in September there was evidence of vehicles being driven from the end of the new hydro onto the peatlands – doing yet more damage!

Whether this was caused by vehicles being driven onto the peatland to restore it or for some other purpose is unclear.

The scandal in Glen Falloch is just as bad as on the Pitmain Estate in the Cairngorms National Park, which I covered last week (see here). There SNH is paying for peatland restoration on the one hand while allowing the landowner to trash the peatland on the other through uncontrolled ATV use. There is a bit of a theme here – a lack of joined up thinking. The only people who benefit from this are the landowners.

What needs to happen

Our hills and wider countryside have a key role in tackling climate change, they not only currently hold large amounts of carbon in their soils they have the potential to absorb more out of the atmosphere. That is why covering the countryside with solar panels is such a stupid idea. What we need to do as a matter of urgency is to start assessing all developments in the countryside from the perspective of their net contribution to climate change. Our National Parks should be playing a key role in this.

My suggestions for action – there is no reason why this shouldn’t be immediate – include:

- Adapting the windfarm carbon calculator so it can be used to assess the carbon balance sheet of all other forms of renewable development in the countryside

- That a further carbon calculator be developed to work out the carbon impact of new hill roads – this would strengthen the Cairngorms National Park Authority’s presumption against new hill roads on landscape grounds

- That the LLTNPA commissions independent research to assess retrospectively the carbon balance sheet of a range of hydro schemes, including Ben Glas, in the National Park. The purpose of this research should be to inform new National Park and national planning guidance on the impact of hydro schemes on soils, including peat bogs. New guidance should also cover the wider issues around the impacts of hydro schemes on the environment and their design.

- That payments to landowners for peatbog restoration should only be agreed where it can be shown that they are not damaging soils elsewhere on the land they own.

A very thought provoking post, Nick. What we are seeing are the results of a broken planning system and the Scottish Government’s ‘window dressing’ response to climate change. Already huge environmental damage has been permitted to happen. The Scottish Government, SNH and Planning Authorities in rural areas need to urgently address the problems and take heed of what you say in “What needs to happen”. My concern is that I don’t think any of these publicly funded entities are listening!