Almost the first newspaper article I read on return from the Pyrenees was about an Innovation Challenge launched by Forest and Land Scotland to increase the number of seeds from trees which are planted that develop into saplings (see here). Apparently two thirds of seeds planted for forestry purposes in Scotland never make it due “to weeds, pests, drought or failure to germinate”. Forestry has now been fully devolved to the Scottish Government who have increased planting targets partly to help absorb carbon from the atmosphere. They announced recently that 11,200 hectares of trees were planted last year “smashing” the 10,000 hectare target. All this means that demand for seedlings is increasing rapidly. Hence this competition which is focussed on finding “technological” solutions to improve seed productivity.

The implications of this approach have not been spelled out. Monsanto and other agri-chemical giants have been developing ways to improve crop productivity for years. They will no doubt see this as an opportunity to argue that if only the Scottish Government would allow the genetic modification of tree we could make them more resistant to “weeds, pests, drought”.

A much better solution for expanding forest cover was evident almost everywhere we walked in the central Pyrenees (see top photo). Nature could do most of the job for us.

At the end of the 19th Century, the consequences of human land-use in the Pyrenees was not unlike Scotland. Forests had been cut down for their timber and intensive grazing had created bare hillsides (a similar situation could be found in the Dolomites and other European mountain areas).

Trees then started to be valued, far earlier than they were in Scotland. This was partly due to the consequences of deforestation, avalanches and flooding. At Gavarnie, from the 1890s, the commune undertook engineering work to stabilise the hillsides to stem the avalanche threat but then realised trees could do the job as effectively. While the reforestation was initiated with some planting, it now appears to look after itself through natural regeneration.

Across the border, the origins of the Ordesa National Park lie in campaigns at the start of the 20th Century to save what remained of the forest there from logging. The canyon was declared a National Park in 1918 and the lower parts have been left to re-wild ever since. The consequences are stunning, with an amazing variety of woodland: pinewoods (Scots Pine and Mountain Pine – Pinus Uncinata), beechwoods, riverine woodland etc.

Walking up the GR11, the long distance walking route which traverses the length of the Pyrenees on the Spanish side, to the main canyon I was struck by a number of oak saplings alongside a section of path where there was not a mature oak tree in sight.

The answer to how they started growing here lies in nature. The most likely explanation is that the many jays which inhabit the woodland at some point stashed acorns which they then forgot. Great tree planters, who don’t cost a penny. Jays are a retiring bird and difficult to see but their screeches are a relatively rare sound in Scotland. That’s probably not unconnected with the fact that in Scotland jays are not protected, not even in our National Parks. They can be trapped and killed by land-managers, under the terms of the General Licenses issued by Scottish Natural Heritage.

The bulk of the reforestation which has been taking place in the Pyrenees, however, is not a consequence of any deliberate decision to conserve land, whether for nature or to protect human settlements, but of agricultural abandonment. While there are still plenty of highly grazed areas – the upper part of the Ordesa Canyon is sadly as overgrazed as anything in Scotland – everywhere you go there are areas of land which are no longer farmed or grazed. Wherever this happens, you can see the trees coming back. Tell tale signs include hillsides covered in young trees and, on lower slopes, overgrown terraces.

This process has been going on for some time and in many places the trees are now mature and you have to look closely below the trees to appreciate the history.

One key difference with Scotland, which has enabled forests to expand again, is that where grazing pressure from domestic animals has reduced, its not been replaced by grazing pressure from wild herbivores such as red deer.

Another key difference is that while many places in the Pyrenees are still heavily grazed, this grazing only takes place for only a limited period each year rather than year round as in Scotland. Cattle and sheep are both moved downhill and/or inside in winter. This creates a “breathing space” from the grazing pressure and allows some trees to survive. These can then act provide a seed source which enables abandoned grazing areas to regenerate naturally and fairly quickly.

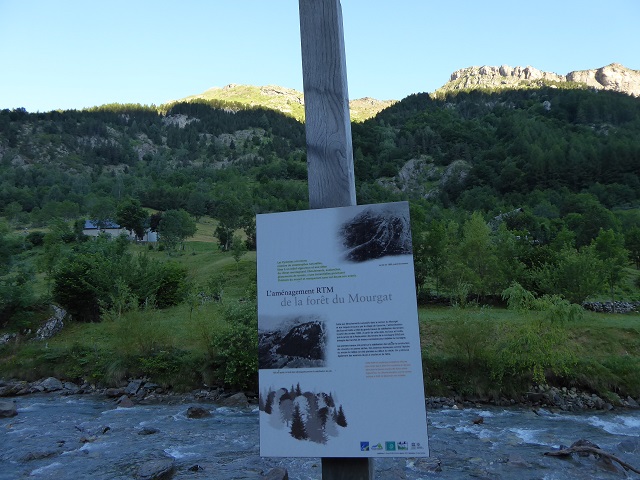

In two weeks we did walk through one planted forest plantation:

The experience was all too reminscent of being back in Scotland – and not just because of the rain!

While I don’t dispute that we may need to plant some trees, the history of planting trees in Scotland has been in many ways disastrous. Subsidies have resulted in trees being planted in the wrong places, like peatland, where draining the ground releases carbon into the atmosphere. Then, quite often the trees die anyway because planted on waterlogged ground or inappropriate soils. Grazing by animals then destroys many, either because predator persecution means there is nothing to keep vole and hare numbers in control (trees manage to regenerate quite successfully in the Pyrenees without plastic tubes!) or because fences are not maintained. Deer then get in, take advantage of the bounty and stop any natural extension of the forest as it matures. Tree monocultures create plagues of insects, such as the pine beauty moth, which then destroy them . They also facilitate the spread of diseases, such as those caused by phytopthera ramorum, which Forest and Land Scotland then “manages” by felling the affected forests. Muirburn gets out of control and into forests which then burn.

If abstracting carbon from the atmosphere is the policy aim, there is plenty of evidence, both from the disaster that is forestry in Scotland and from abroad to tell us that planting trees on an industrial scale is not the best way of doing this. It would be more effective and cheaper to tackle grazing and then let natural processes get on with the job.

That, however, would mean challenging the way land is managed and owned in Scotland. There is lots of hunting in the Pyrenees outwith the National Parks where its banned, but this is not controlled by landed estates and follows a totally different model. The problem in Scotland are the deer stalking estates, which deer numbers have been far too high now for over 40 years, and grouse moors, where muirburn destroys natural regeneration. While this is now being challenged in a few places in Scotland, particularly through the landowners involved in Cairngorms Connect (see here) – the parallels between the natural regeneration that is taking place in Glen Feshie and the Pyrenees are there for all to see – very little lead has been given by the Scottish Government which is effectively in thrall to the landowners. The consequence is that instead of using the climate emergency as another good reason to reform the system of landownership in Scotland, government and its agencies is reduced to launching the occasional “Innovation Challenge”.

The low level of tree cover in Scotland – its only half the European average – is not something that is going to be fixed by technology but by political action. This is an area where our National Parks could and should be giving a lead. They should be setting targets not for the number of trees that will be planted but rather for the area of land where natural regeneration is taking place. They could then agree a suite of actions which would stop the damaging land management practices that prevent forests expanding through natural regeneration in Scotland (from banning muirburn to stopping the persecution of species like jays and foxes).

Gallic shrubs – Why France’s forests are getting bigger. Some additional background.

https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/07/18/why-frances-forests-are-getting-bigger

Brilliant, thank you……………

And just look at the walk up to Creag Meagaidh. Clear the sheep, deer down to 10% of pre 1986 population, and the forest regrows, starting with rowan. The winter thrushes crap out the seeds in a pellet of fertiliser! The rest follows.