The consultation on the second five year Cairngorms Nature Action Plan was launched on 20th June and closes on Friday 14th September at 5pm. The draft plan is easy to read (just 36 pages with big print and lots of photos) and there in an online survey form which focuses on whether the aims, objectives and targets set out in the plan are right. You can access both here. The CNPA has been encouraging people to respond, which is great, but there is a danger in such surveys as the aims and objectives of plans, whatever they are, are usually phrased in a way which are hard for anyone to object to – who would not want landscapes brimming with wildlife? The difficulty is such statements mean very different things to different people – think of grouse moors brimming with grouse, at least until this year, but not much else – and statements in themselves do not lead to change. This post is the first of two taking a critical look at some of the issues underlying the plan.

The context of the plan

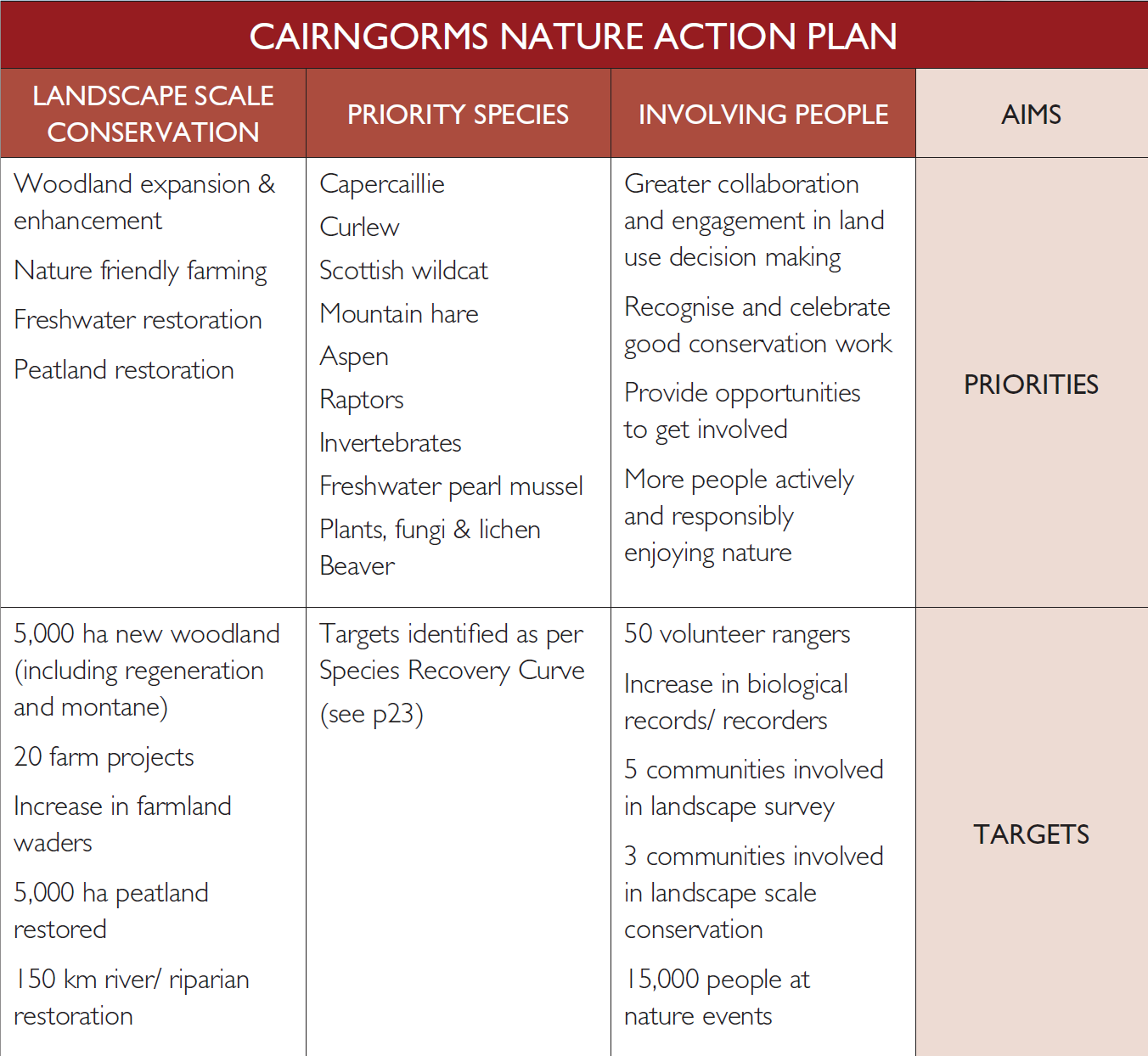

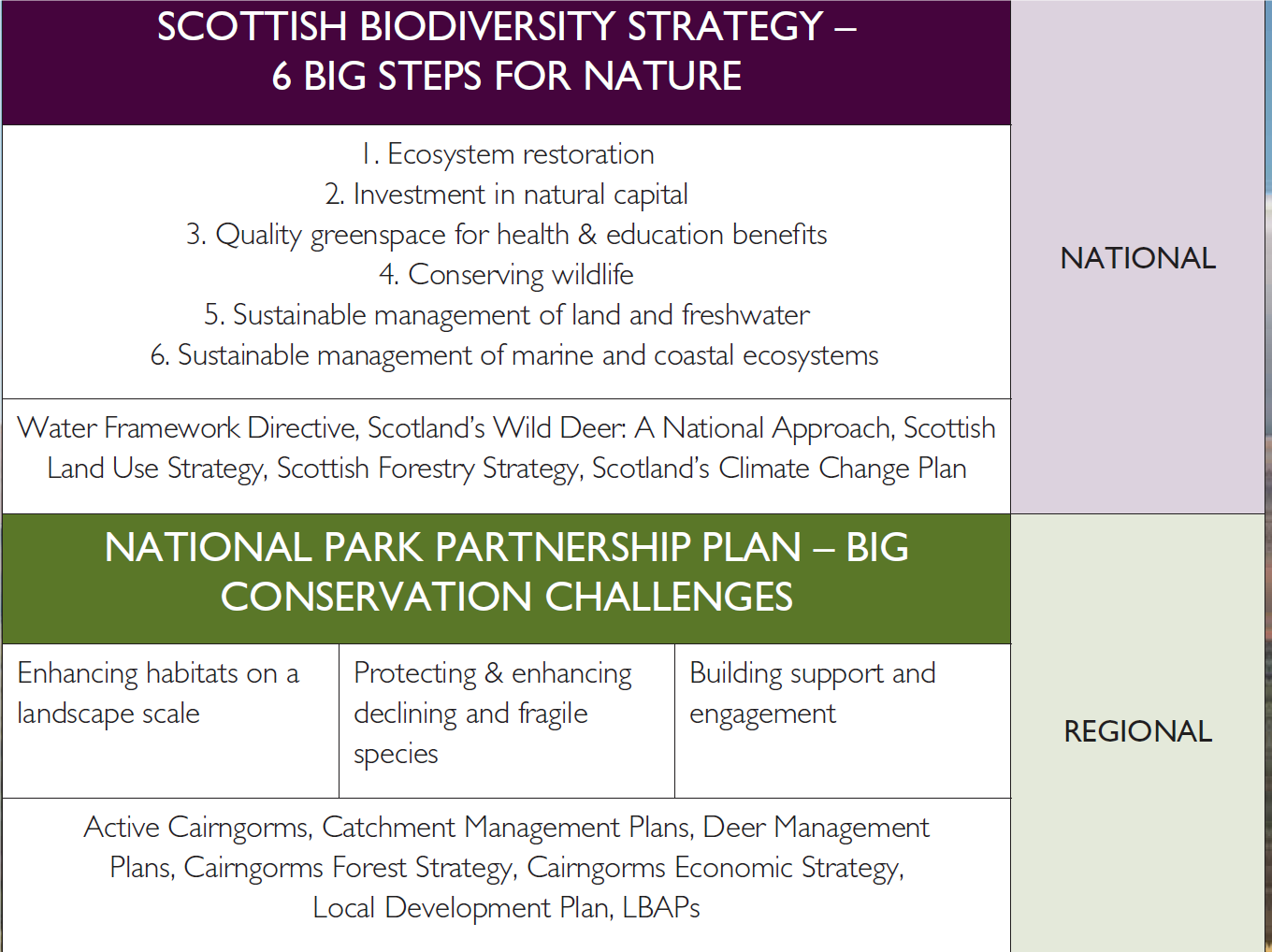

The first Cairngorms Nature Action Plan (CNAP) evolved out of a former biodiversity strategy and its main objectives, such as landscape scale restoration, were set in the National Park Partnership Plan (NPPP) which was agreed and approved by Roseanna Cunningham, the Cabinet Secretary for the Environment, last year.

Under landscape scale conservation, there are four priority areas in both the NPPP and CNAP and three of them (woodland expansion, freshwater restoration and peatland restoration) together with their targets are the same as was agreed last year. Its difficult to under why the CNAP online survey asks about them unless the CNPA is tacitly admitting that the priority areas and targets in the NPPP may already be out of date?

That that might be so is suggested by a change in the fourth priority. The CNAP makes NO mention of restoring natura sites to favourable condition – the fourth priority in the NPPP – but instead has created a new fourth priority of “nature friendly farming”. This is not mentioned in the NPPP.

Conspiracy theorists will note there is not a single reference in the CNAP to the natura designations of Special Protection Area (birds) or Special Area of Conservation, let alone Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Ramsar (protected wetlands) sites or the new National Nature Reserves that have been designated in the Cairngorms. Surely, the CNPA needs to explain somewhere the role of designated sites in conservation?

This devalues the whole consultation (and there are some positive things in it). The CNPA should have been clear about what objectives had already been set and are in effect non-negotiable and carried all of these over into the plan. The consultation could then have focused on asking people about changes and refinements to the National Park Partnership Plan in respect to nature and then focussed on how it should be delivered. (The very term Action Plan suggests its about delivery, not changing objectives). Unfortunately the consultation focusses on objectives, not delivery.

Landscape scale conservation – farmland

Having expressed reservations about the lack of clarity about changing priorities, I welcome the addition of farmland to the list of landscape scale priorities. It is about time our National Parks grappled with the issues associated with the intensification of farming that has taken place even in marginal areas (like those in the Cairngorms), the impact this has had on wildlife (loss of meadows etc) and what they could do to make farming more sustainable.

The CNAP proposes two areas of work for this priority:

- “more habitat suitable for breeding waders as part of agricultural systems”, and

- “wildlife-rich grassland and woodland on productive, profitable farms”.

The first area appears driven by the news of the collapse in wader numbers across Scotland (though positively the CNPA has apparently bucked this trend slightly) and linked to this the curlew has been added to the list of priority species. Good stuff.

The value being put on wildlife rich grassland is also positive given the history of field improvement in the National Park which has destroyed wildlife, sometimes deliberately so to pave the way for housing development. But what on earth have “profitable” farms got to do with conservation? Its competition and the drive for profit which has destroyed wildlife. The word that should have been used is the one in the CNPA’s statutory objectives “sustainable” – not the same thing at all as being profitable.

And that points to the fundamental problem here, the CNPA’s belief that “nature friendly farming” is possible in a free market system. To me their aspiration of “Delivering biodiversity benefit is an integral part of high-quality food production and does not impact on profitability” is motherhood and apple pie. The reality is farmers who want to be eco-friendly are up against our economic system the whole time.

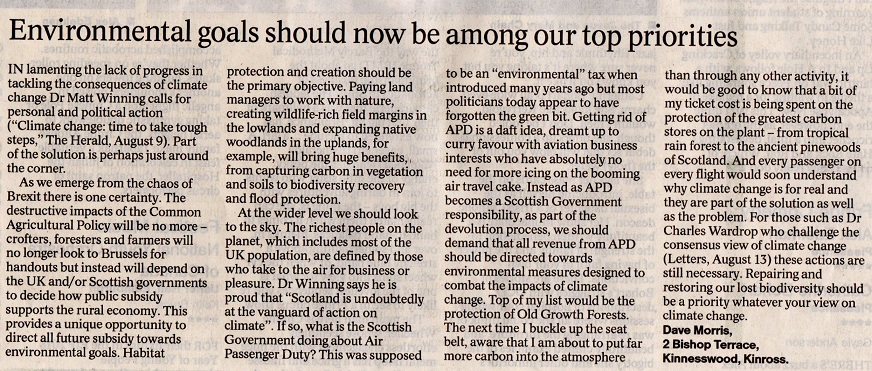

Instead of supporting the current system, what our National Parks could very usefully do is work with farmers and conservationists to develop proposals for how financial support to farmers would need to work to achieve “nature friendly farming”. As Dave Morris pointed out in a letter to the Herald yesterday, Brexit offers a great opportunity to do so:

So why shouldn’t the CNPA take the lead on this and, having put nature friendly farming on the agenda, why then limit this to waders and grassland? What about all the other birds that used to thrive in farmland? Could not the CNPA and farmers in the National Park do more for the yellow hammer, corn bunting and tree sparrow and enable far more people to enjoy these birds again? Why not even think about re-introducing the corncrake? I would have liked to have seen the consultation on farmland priorities put forward within a more holistic analysis of the issues.

So why shouldn’t the CNPA take the lead on this and, having put nature friendly farming on the agenda, why then limit this to waders and grassland? What about all the other birds that used to thrive in farmland? Could not the CNPA and farmers in the National Park do more for the yellow hammer, corn bunting and tree sparrow and enable far more people to enjoy these birds again? Why not even think about re-introducing the corncrake? I would have liked to have seen the consultation on farmland priorities put forward within a more holistic analysis of the issues.

Landscape scale conservation – freshwater restoration

There has been a lot of good work going on in the National Park on restoration of natural river systems (driven in part through water catchment management plans) and the CNAP proposes another 150km of rivers should be restored. That all sounds good, but there is one big gap:

Many of the main rivers and burns within the south west quarter of the Cairngorms National Park are diverted into the Tummel hydro scheme which was constructed in the 1940s. It has affected rivers more than anything else but the plan is totally silent about the issues and whether any improvements might be possible (allowing at least some water flow at all times, as happens with run of river hydro schemes, would be a start). I will not say more here because parkswatch is planning to publish a post on the ecological impacts of large scale hydro schemes in the near future.

Landscape scale conservation – woodland expansion

The consultation document is brave enough to admit that officially the target of 5000 hectares of woodland expansion set in the last plan was missed (c3000 ha planted) but then acknowledges that there has been no proper assessment of what is being achieved by natural regeneration. While that might appear an incredible omission, since natural regeneration of the Caledonian Forest has been talked about for so long, I think its a reflection that large scale natural regeneration is only now really beginning to happen.

Part of the explanation for this lies in the time it has taken to bring deer numbers down sufficiently for tree saplings to survive and grow large enough to seed. While Glen Feshie has arguably taken the most radical approach to deer culls, both it and the other areas owned by Wild Land Ltd have for a long time been affected by deer incursions from neighbouring estates. However, through Cairngorms Connect, which provides a framework for co-operation between Glen Feshie, SNH, Forest Enterprise and the RSPB at Abernethy, and with first Mar Lodge and then this year Atholl increasing their deer culls, regeneration is now able to take place over a far far wider area.

This is a great success and should be celebrated. Its very positive therefore that natural regeneration is given a prominent place in the CNAP (far more so than in the consultation on the Indicative Forest Strategy (see here)).

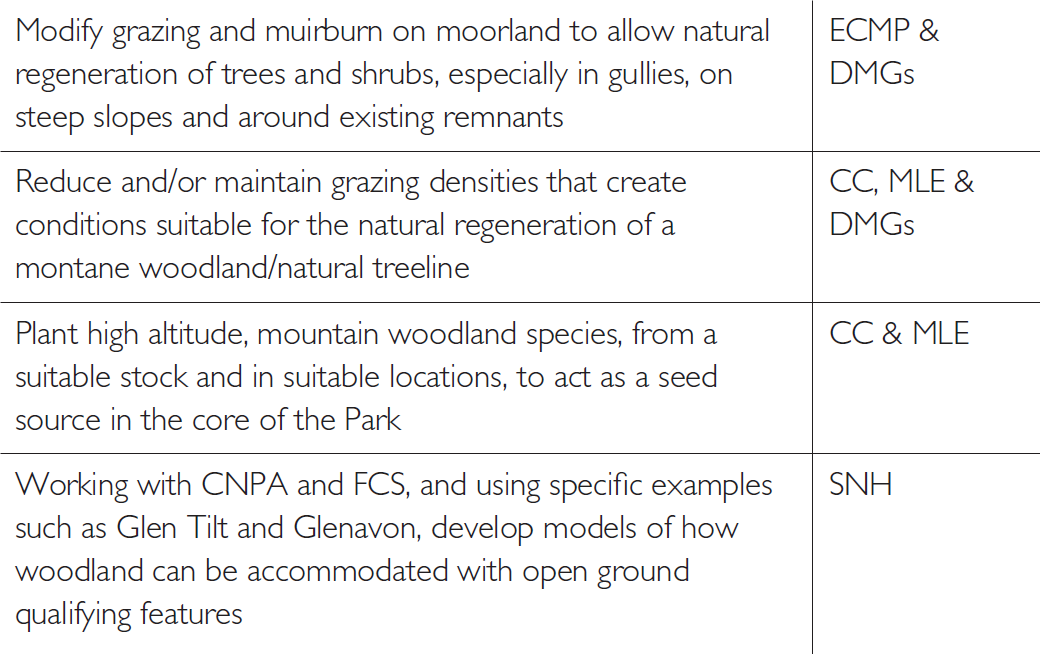

Lets hope the draft Forest Strategy – which overlaps significantly with the CNAP – will have been revised to reflect the key role of natural regeneration in the National Park before its presented to the CNPA Board in September for approval. There are, however, still two problems with the actions as currently proposed.

The first is that, while in theory it should be easy enough for land managers to modify where muirburn takes place, the only way you can modify grazing impacts in specific areas, as proposed, is by fencing. So, is the CNAP proposing miles of new fencing – the word does not appear once in the document – around gullies and existing woodland remnants? This was an option rejected by Wild Land Ltd which has gradually removed fences on its estates as deer numbers reduce. The proposal to modify grazing in specific areas would be unnecessary if the second action, of reducing deer numbers sufficient for a natural treeline to develop, was implemented.

This apparent muddle is explicable if the CNPA are thinking of a reduction of deer numbers in some areas and fencing/modification of muirburn in others. If that is the case, the consultation should have asked which areas were appropriate for the different approaches. Unfortunately the action plan is not really an action plan at all because it does not say where actions will happen. My belief is its what happens on the ground that counts.

The second problem is that the CNAP proposes planting montane scrub species “as a seed source in the core of the Park”. This proposal appears to have come from Cairngorms Connect, many of whose members appear keen to see a montane scrub zone on THEIR land (see here). Now, I share an aspiration to see far more montane scrub zone and there is a case for planting in the most degraded areas of the National Park such as the Angus Hills, but why do this in the very areas where natural regeneration is working?

The justification given in the CNAP is to establish a seed source although nothing is said about for what species and why. While some people are arguing from the paucity of specimens of certain species, of willow for example, that unless we take action by PLANTING those species they will disappear completely, this is undermined by the CNAP. The section on priority speciesincludes just one montane scrub species, the woolly willow (found between 600-900m) and this is now rated S1 “population/range targets being achieved with minimal intervention” – its in fact the species least at risk on the whole list.

The problem is that people who rightly want to see a flourishing montane scrub zone are impatient. Yet all the evidence from lower down is that regeneration takes time. When I visited Glen Feshie with Reforesting Scotland earlier in the summer we spotted Salix Lapponum or downy willow among the regenerating pine on the floor of the glen – the first time our guide, Wild Land Conservation Manager Thomas MacDonnell, had seen it there. This species has a much wider altitudinal range than woolly willow and is often proposed for montane planting. If it can get to the floor of the glen it can get to its rim, it just needs time – just like after the ice ages. If some species really are threatened and need protection, then the answer is plant them somewhere else – I am confident that given time, they would colonise the core area. We should however be keeping areas like the “core” of the Cairngorms wild, somewhere where natural processes are allowed to run their course without any human intervention except the culling of deer. Our arrogance is to think we can do better than nature.

On a positive note, unlike with farming which is to be left to the market, the CNAP woodland section does identify finance as an issue which needs to be addressed both for natural regeneration and woodland planting:

Investigate, develop and deliver models for funding woodland expansion and enhancement to work in addition to, or alongside, Forest Grant Schemes eg Forest Carbon

Culling deer incurs significant costs and if land managers are to reduce deer in the remote “core” of the Cairngorms without constructing yet more hill tracks the costs will be even higher. This can never be recouped from commercial stalking/sale of venison and it is not reasonable to expect a few landowners to pay for this in the long-term while others are not pulling their weight. We need to put the question of public support for public goods back on the table and again Brexit provides an opportunity for the CNPA to do this.

Landscape scale conservation – peatland

The CNAP says peatland restoration is about “actively managing the carbon and water functions of the uplands” and the target is carried over from National Park Partnership Plan and yet another plan, the Peatland Action Plan. Its good stuff but very little is said about this except:

“Work with a range of land managers across the National Park at sites where peatland restoration will deliver increased sub-catchment scale ecosystem benefits and where large herbivore densities and burning activity will maintain restoration efforts”.

The message is clear but the implications not spelled out. Unless deer are culled and muirburn ceases there is no point restoring peatland, because it will be destroyed again. What that means is that in some of the areas where peatland restoration is most needed to reduce/prevent flooding, on the grouse moors above Ballater for example, it appears unlikely to happen.

That points to another major issue, “partnership working” which I will consider along with the proposals to protect species in another post.