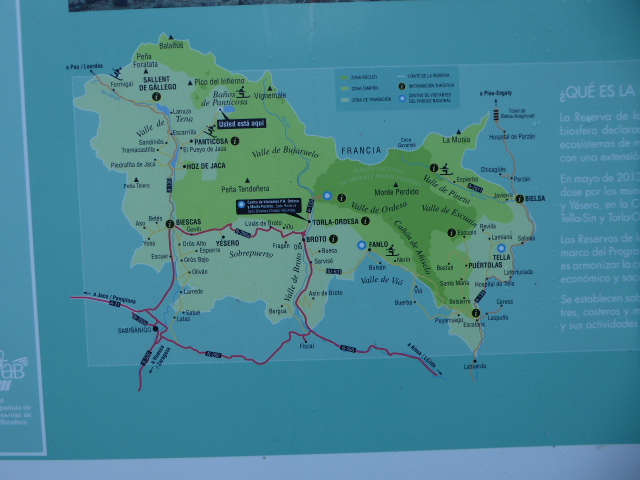

The French Pyrenean National Park and the Ordesa and Mont Perdido National Park are much smaller than our two National Parks in Scotland but surrounded by large buffer zones where the National Park influences what activities take place and how land is managed. In the National Parks themselves there is no permanent human habitation and human activities are tightly regulated with a complete ban on hunting. While at first sight a very different model to our National Parks, in effect the Pyrennean National Parks comprise a core area which is treated as a nature reserve, akin to our wild land areas or the former Cairngorms National Nature Reserve. Around them are peripheral zones, where the National Park influences how the land is used and where more economic activity takes place: akin to the inhabited glens and straths of our National Parks.

Were our National Parks to adopt a zoning system, with core areas protected for nature, the two models would not appear that different.

A far more significant difference, from which we could learn a lot in Scotland, is how agricultural activity is changing and is being managed, both within the designated National Parks and the peripheral zones.

In the Pyrenees, like other mountain areas in Europe, agriculture is in retreat notwithstanding the EU subsidy system. Land previously used for agriculture is being recolonised by nature, with the development of tall plant communities (foreground of photo), scrub and forest. In time, this should benefit the bears in the Pyrenees, which have been reduced to a handful, and will help absorb carbon out of the world’s atmosphere. The contrast with the Scottish Highlands, where agriculture in the form of sheep farming has also been in retreat, is stark. In the Highlands, sheep are being replaced either by deer or by grouse moor and the land either grazed or scorched bare. The consequence is that in Scotland the retreat of farming has seen no re-wilding dividend.

Significant pastoral farming activity, however, still takes place within the French Pyrennean National Park and the Spanish peripheral zones. This grazing by farm animals has a significant impact on the ground flora, promoting grasses at the expense of flowers and many areas are as a consequence quite restricted botanically – again not dissimilar to the Highlands.

What I found striking though is HOW this pastoral activity is managed. There were almost NO agricultural tracks and we saw NO sign of vehicles being used off track!

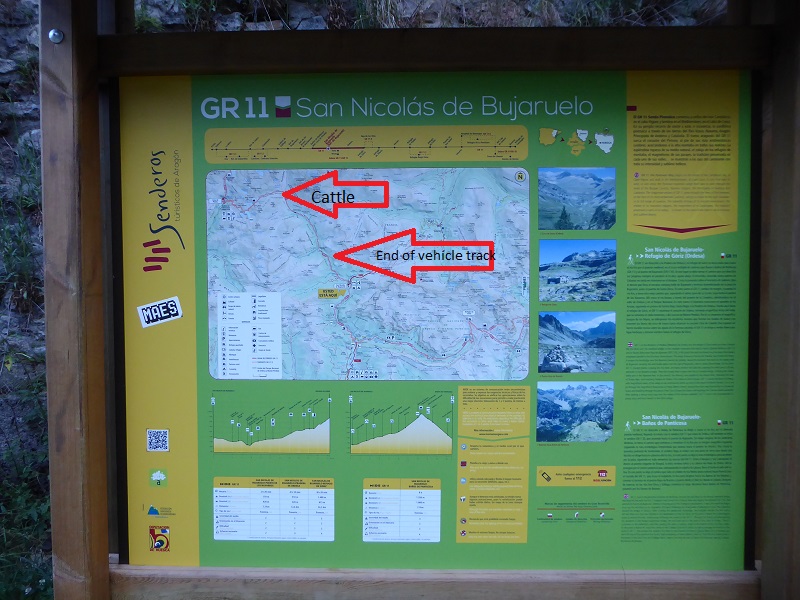

We spent several hours walking up the Valle del Ara, on the south side of Vignemale, through flower rich ungrazed areas before coming across large numbers of cattle in the upper part of the valley:

Unlike in Scotland, the landscape impact of this farming activity is limited because of the lack of vehicle tracks:

Contrast this with the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park where senior planning staff, under delegated powers, reversed the original decision of the Board and allowed tracks used to construct hydro schemes to remain for “estate management purposes”:

In Glen Falloch there are cattle, just like in the Pyrenees but less woodland and tracks everywhere. If they can manage cattle or sheep miles from the road end in the Pyrenees without tracks or vehicles, why can’t we do the same in our National Parks?

I checked on my map afterwards and the cattle we saw in the Valle del Ara were over 5km from the end of the vehicle track. This was not atypical and in several valleys we came across cattle over 4km from a track.

In the Valle del Ara there were cattle even higher up about three hours walk from the end of the track. If Shepherds can walk in the Pyrenean National Parks and surrounding areas, why can’t they do so in Scotland?

What the example of the Pyrenees shows is decisions about how to manage agriculture and pastoral activity in National Parks are a matter of choice. In Scotland our National Parks have been making choices that favour landowners and farmers and have taken very little account of the landscape. It need not be like this.

Brexit, whether it happens or not, provides an opportunity to rethink how agriculture is practised in the Highlands and what subsidies should be paid to landowners. Our National Parks should be playing a key role in developing new models of agriculture. I would like them to go further than the Pyrenean National Parks, and not just ban vehicles in remote areas (and reinstate some the terrible tracks that have been created over the last twenty years) but develop new models of land-use which end all agricultural activity in core wild land areas. In other areas they should be working out what subsidy would be needed for pastoral grazing to be managed on foot, as in the Pyrenees and making the case to the Scottish Government for change.