Three weeks ago the Cairngorms National Park Authority decided to approve the retrospective planning application for a section of the unlawful Glen Banchor track. Its a positive thing that members of the CNPA planning Committee are so concerned about the proliferation of hill tracks – Dave Fallows was right to describe the Glen Banchor track as a “downgrade” (see above) – but the evidence of what has happened at Glen Banchor shows that they still have some way to go if they are to successfully tackle the issues. This post takes a look at the reasoning behind the decision to grant retrospective approval to the track and contrasts this with a recent decision by the Peak District National Park Authority which required a landowner there to remove an unlawful track in its entirety.

Three weeks ago the Cairngorms National Park Authority decided to approve the retrospective planning application for a section of the unlawful Glen Banchor track. Its a positive thing that members of the CNPA planning Committee are so concerned about the proliferation of hill tracks – Dave Fallows was right to describe the Glen Banchor track as a “downgrade” (see above) – but the evidence of what has happened at Glen Banchor shows that they still have some way to go if they are to successfully tackle the issues. This post takes a look at the reasoning behind the decision to grant retrospective approval to the track and contrasts this with a recent decision by the Peak District National Park Authority which required a landowner there to remove an unlawful track in its entirety.

The CNPA is allowing tracks to get planning consent by the back door

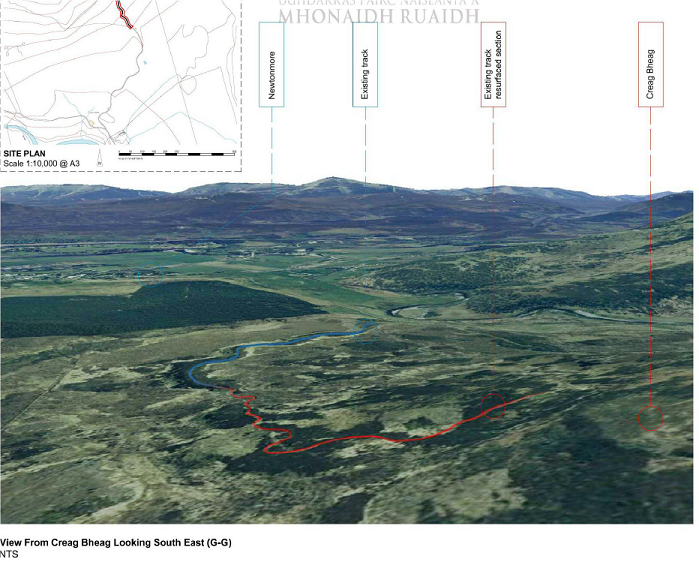

Back in June (see here), following the Glen Banchor Estate’s submission of the retrospective planning application to the CNPA, I argued that the whole track from the road to the sheep pens on Creag Beag should have required planning consent. While I failed to submit an objection in time (mea culpa but the CNPA only allows 28 days, the statutory minimum, for the public to do this) both Mountaineering Scotland and the Badenoch and Strathspey Conservation Group lodged excellent objections which made this point Item7Appendix2RepObjections.

The CNPA rejected their argument claiming:

24. The CNPA served a Section 33A notice requiring a planning application for the upper section of this track where significant upgrade and construction had re-engineered the previous small vehicle track, most suitable for ATV traffic rather than normal four-wheel drive vehicles. The lower section of track travels along a natural ridge of sand and gravels and was suitable for use by normal four-wheel drive vehicles. The lower section of track has been used more frequently by estate and construction traffic so has lost vegetation and in some places, had repairs and maintenance undertaken to its surface. However, these works are limited and are legitimate maintenance of a long-establised track. The works to the upper section of track are significantly more extensive and require authorisation. The planning application has responded to the Section 33A notice.

The assertion that the lower section of track had “lost vegetation is some places” due to use of vehicles is not supported by the visual evidence:

So, why was the CNPA not prepared to challenge the estate on this point and require a retrospective application for the whole track which could have ensured any planning conditions applied to all of it?

My suspicion is the application is a compromise which was reached in order to avoid the CNPA being involved in a protracted legal battle. The problem is classifying the work on the lower section of track as “legitimate maintenance” sets a terrible precedent. It would appear to indicate that the CNPA is quite happy that other tracks, for example those on the plateau at the head of Glen Prosen (see here) should be “upgraded” in a similar way:

This opens the way for ATV upgrades throughout the National Park.

The second major problem with the Glen Banchor decision is that it based on a claim that “the principle of development” can be established by the use of vehicles over a long period of time:

APPRAISAL

16. The principle of a vehicle track in this location is established by the fact that there has been a small track, used by vehicles as well as walkers over a long period of time. The upgrading work undertaken has significantly re-engineered the construction of the previous rough and narrow track to a wide vehicle track.

What this appears to say is that wherever there is a longstanding track caused by ATV or other vehicle use the CNPA will accept the principle of development has been established and will therefore not object to planning applications for such tracks being upgraded into a full track (so long as they meet certain standards). On this argument all an estate has to do is use ATVs on the same route over a sufficiently long period of time and the CNPA will then accept the case for a track has been established in principle. This drives a cart and horses through the welcome statement they made in their Partnership Plan that there should be a “presumption against new vehicle tracks” in the uplands.

In the case of Glen Banchor track, there is already such an ATV track which leaves the track newly granted planning permission near its highest point. The Badenoch and Strathspey Conservation Group rightly, in my view, asked the Planning Committee that further use of this ATV track should be forbidden to prevent track creep.

21. The Convener invited Tessa Jones from Badenoch and Strathspey Conservation Group to address the Committee. The following point was raised:

a) The Convener clarified that the CNPA cannot add a condition to block all future development as further applications may be submitted in the future (Extract from draft Minute of meeting).

The CNPA’s response appears to be that even if there is strong evidence that tracks are likely to be extended in future, they can do nothing in planning terms to prevent this happening. In fact in the case of the Glen Banchor track extension there is evidence to show this is not just a result of ATV use but has been deliberately constructed:

Unfortunately the Committee Report did not include any photos of this section of “ATV” track or of the works on the lower section of track which might have enabled the Planning Committee to reach a different conclusion and as a consequence they are allowing track proliferation to continue by the back door:

CONCLUSION

25. The development undertaken is acceptable in principle as it is an upgrade to an existing track but has not been undertaken in a way that uses best practice or complies with policies in the Local Development Plan. In order to minimise the impact of the track on the landscape and natural heritage it is necessary to impose conditions on an approval to make the development acceptable. The alternative would be to require the reinstatement of the previous track, which in this case would be likely to have further significant adverse landscape impacts.

Just why reinstatement of damaged ground would likely to have “significant further adverse landscape impacts” when both our National Park Authorities have granted permission to construction tracks for hydro schemes on the basis that the ground can be restored successfully is unclear. The implication, within this context, seems to be that the CNPA trusts neither the Glen Banchor Estate nor their agents, Savill’s, to do such restoration the work properly. If that is the case, it suggests the CNPA believes existing enforcement powers are insufficient to guarantee an appropriate standard for works and they should be calling for whatever powers they need to be included in the Planning Bill currently being considered by the Scottish Parliament.

Other aspects to the planning consent

On the positive side the Committee Report recommended the upper section of track be reduced to 2m in width so it can ONLY be used by ATVs and is far more like a path (the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority could usefully adopt this as a standard for hydro access tracks too). It also includes some measures to improve landscape and reduce erosion.

There is, however, strangely, NO reference in the report to SNH’s Guidance on Hill tracks (see here) despite both the Badenoch and Strathspey Conservation Group and Mountaineering Scotland arguing in their objections that any planning consent should adhere to the standards set out in it. Had the CNPA abided by those standards it would, I believe, have had to reject the section of track contained within the planning application as being too steep.

In addition, despite the Report stating that the “CNPA Landscape Officer considers that the track is highly visible within the landscape” having accepted the principle of development, the only thing CNPA staff could do was recommend measures “that could be used as mitigation against the adverse landscape impact of the track in the medium term.”

Comparison of the CNPA decision-making process with the Peak District National Park

In June the Peak District National Park took the decision to require the unlawfully created (plastic) track on Midhope Moor to be removed in its entirely. You can read interesting background on the application in a blog by Paul Besley and the refusal was no doubt made easier by the 187 objections to the application (compared to just two at Glen Banchor with no response from the local community council in Newtonmore).

I believe both our National Parks could learn from the robust policies of the Peak District National Park and reasoning of staff in the Committee report (see here).

The first is that the PDNPA has established different planning zones within the National Park and:

9.1. Principle of development in the Natural Zone.

The application site lies within the Dark Peak Open Moorland area of the National Park

which is designated as Natural Zone. In this area, Development Plan Core Strategy Policy

L1 states that ‘other than in exceptional circumstances, proposals for development in the

natural zone will not be permitted’

Were the CNPA to zone areas within the National Park like this, they would avoid the whole issue of track creep and the principle of track development being accepted incrementally over the years through ATV use. As I read it, in the Peak District that CANNOT happen as they have adopted a policy against development in Natural Zones except in the most exceptional of circumstances. And the Peak District National Park polices give this real bite by defining exceptional circumstances as:

“those in which a suitable, more acceptable location cannot be found elsewhere and it is essential: (ii) for the management of the Natural Zone; or (iii) for the conservation or enhancement of the National Park’s valued characteristics”. It goes on to state in LC1(b) that ‘Development that would serve only to make land management or access easier will not be regarded as essential.”

These robust policies appear to have empowered staff to take a robust stance:

6.24. PDNPA Landscape Architect – Object – Highly significant impact which is not possible to

mitigate.

Summary of detailed comment;

This is development within the natural zone and can therefore only be justified in exceptional

circumstances.

I am unsure why a permanent vehicular track is required to facilitate ongoing restoration

works – this would only be necessary for the duration of the restoration works?

After the track was installed it was highly visually intrusive and it is accepted that the visual

effects of the track have reduced over time; however, the track is still a visually intrusive and

incongruous development in the natural zone.

The new track has also not been laid on the route of the previous eroded track – and this

eroded route has not been restored. Given that, I do not support the application

What’s more they rejected the pathetic advice from Natural England, which like SNH has been emasculated, who had no objection to the development.

Of course, were the CNPA to adopt a policy stating development in Wild Land Areas or National Scenic Areas for example would only be permitted in exceptional circumstances, that would not have included the area where the Glen Banchor track is located and therefore addressed the issues in this case. It would however stop track creep in the central Cairngorms and other areas, like the head of Glen Prosen, and other policies could be adopted to prevent track creep close to settlements.

The other really interesting point in the Peak District National Park Authority Committee report is their reference to the Sandford Principle which states that where there is a conflict between the National Park’s objectives conservation must come first:

Policy GSP1 sets out the broad strategy for achieving the National Park’s objectives having

regard to the Sandford Principle, (that is, where there are conflicting desired outcomes in

achieving national park purposes, greater priority must be given to the conservation of the

natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage of the area, even at the cost of socio-economic

benefits). GPS1 also sets out the need for sustainable development and to avoid major

development unless it is essential, and the need to mitigate localised harm where essential

major development is allowed.

Note how conservation needs to come before “socio-economic” benefits (or benefit to landed estates). Our National Parks are supposed to put their statutory conservation objective before others (public enjoyment, sustainable economic development and wise use of resources) but sadly almost never do so in practice. They could learn from the Peak District to be brave and take on vested interests such as landowners (strangely there is no evaluation in the Committee Report of whether this track was really needed or not).

And finally its worth noting the robust recommendation in the report:

3. RECOMMENDATION

That the application be REFUSED for the following reasons:

1. The justification for the access matting advanced in the applicants supporting

statement does not amount to exceptional circumstances to warrant development

in the Natural Zone. The proposal is therefore unacceptable in principle and

contrary to policies L1, LC1, GSP1-3 and paragraph 115 and 118 of the NPPF.

2. The adverse visual impact of the matting itself and the consequent changes to the

vegetation along its length arising from its installation significantly harms the

valued character and appearance of the moorland landscape contrary to polices

L1, LC4, GSP1-3 and NPPF paragraphs 115 and 118.

3. Harm to the moorland ecology and habitat along the length of the application site

from the initial installation of the matting and associated groundworks coupled

with the damage caused subsequently from the increased vehicle use of the route

contrary to policies L2 and LC17.

What needs to happen

If the CNPA wishes its presumption against new hill tracks to be taken seriously it needs to put in place policies and practices that prevent the proliferation of new hill tracks, including through track creep. It could do this:

- By strengthening its Local Development Plan (currently being drafted) so that there is not just a presumption against new hill tracks but so it includes

- clear zones where the “principle of development” of tracks can never be established incrementally or by default

- policies which put landscape and environment before the convenience or wishes of landed estates

- By adopting the Peak District National Park’s policy approach that “permitted development rights will be excluded by means of planning conditions”. This would prevent Glen Banchor coming back and claiming track extensions were for agricultural or forestry purposes – which currently don’t require planning permission.

- By taking enforcement action against unlawfully created hill tracks and requiring them to be removed entirely and the land restored

- By controlling ATV use through use of byelaws

- By forcing estates to provide economic justifications for developments and evaluating these against the CNPA’s statutory conservation objectives

Yes, I agree that CNPA could learn much from the Lake District National Park decisions on hill tracks, but CNPA’s record on enforcement is deplorable. It also can be accused of regularly not upholding the first aim of the National Park (consevation) in favour of the 4th aim (social an economic development). This whole case smacks of a pre-arranged agreement with the estate owner. It’s about time the CNPA Board Members started to lead the CNPA management (especially the planners) and not just do their bidding.