Nestled in the hills behind Newtonmore, Glen Banchor (pronounced Banachar and meaning the horn or bend in the river) is, like so many Highland glens, both beautiful and desolate, a part of that ‘wild land’ image that the Cairngorms National Park Authority and others like to promote as one of Scotland’s great assets. But Glen Banchor has not always been desolate: nor is it a truly ‘wild’ landscape. Walkers passing through the glen while tackling the Munros that ring its north side, or following the East Highland Way beside the River Calder, cannot fail to notice the traces of previous occupation, the ruined settlements, patches of long-abandoned arable, clusters of shielings in the hills. Like all such glens, there is a story to be told, not of wild land, but of human existence, of a people that carved out their lives over many centuries, forging an economy and way of life tailored to that environment, exploiting and managing the landscape to fulfil their needs.

Nick Kempe (see here) recently highlighted the potential risks to this glen under its new ownership, prompting this look at the need not just to protect such areas, but to promote their history. In fairness, the estate has recently fenced off the best settlement site in the glen (and provided access), hopefully suggesting a willingness to protect such sites from any future developments in the area.

Heritage tourism

In general, the CNPA seems reluctant to promote the human side of the Park’s story. Outdoor attractions, leisure and recreation, skiing and walking, scenery and wildlife, not to mention the new and rather dubious ‘snow roads’ experience are extensively promoted – but scant attention is paid to heritage interpretation for those indulging in these pursuits. Heritage interpretation seems to be confined to the very fine museums within the Cairngorms National Park. The Highland Folk Museum at Newtonmore, just a mile or so from the entrance to Glen Banchor, indeed contains a wonderful reconstruction of an eighteenth-century township, an excellent insight into what life in the glen might have been like. But the point is that this type of heritage interpretation lies within the grounds of a museum, even though the real thing (albeit in ruins) is everywhere in the surrounding landscape. The museum would indeed provide an ideal starting point for heritage trails, encouraging visitors to seek out the real context of its exhibits.

Heritage tourism is one of the fastest growing sectors of the business in Scotland. Why not seize on this and create interpretive heritage trails in places like Glen Banchor, to enable visitors to understand the human landscape around them, to appreciate life of past societies, their struggles for survival in such places, and, of course, the story of why not a single soul now lives there.

Tell the real story of the landscape. This is not wild land in the true sense: it was be a wilderness, but it is a man made one. And that surely is a great story to tell. Though it may be uncomfortable to some, that does not mean we should shy away from it. Think of the vast numbers of Scottish diaspora who come ‘home’ to find out more about their families origins – do they not deserve a serious interpretation of their ancestors’ lives? And I don’t mean romanticised ‘Outlander tourism’, nor a simplistic anti-Clearances agenda, but an attempt to present the complexities of Highland life and depopulation. It has been done effectively in other areas, so why not within the Cairngorms National Park?

A ‘managed’ environment

Man has impacted on this area for centuries: from the destruction of native forests to the blanket plantations of ‘commercial’ timber; from the persecution of native species like wolves in the past – and now eagles, harriers and hares – to the mass introduction of non-native species like pheasant and partridge; from ancient peat tracks and peat banks to shooting butts and bulldozed estate tracks; from shieling settlements to wind farms. Man has consistently manipulated the Highland landscape to further whatever were the economic needs of eras past and present. In the eighteenth century the Monadhliaths, right onto the plateau and 3,000 foot tops, were grazed by a balance of cattle, sheep and horses – with intensive cattle-dunging of the shieling areas impacting dramatically on the natural flora and fauna. In the nineteenth, the same hills were subjected to the intensive over-grazing of sheep; more recently, moor and hill were managed to maximise shooting interests with increasing numbers of hand-raised birds and unnaturally high deer numbers. The Glen Banchor hills were patrolled by grass-keepers long before gamekeepers! Everywhere there is evidence of human impact even in the remotest areas: the green oases and bothies that were once the cattle shielings, boundary cairns and marker stones sometimes carved with proprietors’ initials; rusty fence posts and tangled wire traversing the summits of distant Munros; hydro dams and wind farms; the crude scars of recent estate tracks. Is this really ‘wild land’?

An old boundary cairn high above the west end of the glen – a symbol of human presence even in the remotest areas. Photo Credit David Taylor

An old boundary cairn high above the west end of the glen – a symbol of human presence even in the remotest areas. Photo Credit David Taylor

A glimpse into Glen Banchor’s past

The Cairngorm National Park naturally falls within the general trends of Highland history, but each glen and community has its own unique version of that story – as does Glen Banchor. Though not the place for detail, it is worth giving a brief glimpse into the story that could be told.

Traces of occupation going back to Bronze and Iron Age times are still visible, but detailed information does not emerge until the late eighteenth century when the glen was at its population peak.

Then it contained fourteen townships, each a cluster of three to four families, though occasionally more, thus totalling between 40 and 60 families, perhaps 200 to 250 people – probably 300-400 if labourers, servants and cottars are taken into consideration. Between farm houses and outbuildings like barns, corn kilns, and later, byres, there may have been 100-150 thatched buildings (similar to those in Folk Museum) in this small glen. That alone gives a startlingly different appreciation of the environment to anyone traversing the glen, surely begging the question in the visitor’s mind of what life must have been like for those folk.

Then it contained fourteen townships, each a cluster of three to four families, though occasionally more, thus totalling between 40 and 60 families, perhaps 200 to 250 people – probably 300-400 if labourers, servants and cottars are taken into consideration. Between farm houses and outbuildings like barns, corn kilns, and later, byres, there may have been 100-150 thatched buildings (similar to those in Folk Museum) in this small glen. That alone gives a startlingly different appreciation of the environment to anyone traversing the glen, surely begging the question in the visitor’s mind of what life must have been like for those folk.

These townships – now just ruckles of stones and turf outlines – were runrig farming communities with farmers working in collaboration with their neighbours growing their oats and bere, and later, potatoes on small patches of arable ploughed by garrons (native Highland ponies). Arable cultivation here, on the thousand-foot plus contour, was vulnerable to the harsh Badenoch climate, and often there was not enough oatmeal to provide a year-long supply. Livestock thus played a major part in the Glen Banchor economy. On the surrounding hillsides, corries and even the Monadhliath plateau they grazed their cattle – providers of both food and cash – but also sheep and horses, not for a few weeks in the summer, but for over six months of the year. Every mountain burn tumbling down the northern slopes had at least two sets of shielings with still-visible bothies where women and children spent much of that time herding cattle and converting milk into dairy produce for themselves or for sale in the local markets. Some of these Glen Banchor shielings, at 2,500 feet, are the highest anywhere in the Highlands, and well off the beaten track even for the Munro bagger. What a potential experience for the more adventurous visitor or walker to explore these remote mountain corries and pause to reflect on the hardiness of earlier generations.

On the green strath below, particularly the township of Westerton of Glenbanchor (the correct spelling for the farm of that name), the ruins of houses, barns, corn kilns, stack yards, kail yards, head-dykes, can be clearly identified, and there are still lingering traces of cultivation rigs for the discerning eye. But these are not anonymous ruins, for the lives of the people who lived there are well documented and named families can be placed precisely in a particular township, and in one or two cases even a specific ruin, giving the whole experience a much greater intimacy. Catherine Macdonald, for instance, a widow, struggled to bring up her four children at Westerton, running the farm until her sons were old enough to help out. When the condition of her house (and all the others) was criticised by the estate, she rebuilt her entire house and farm buildings in 1875, buying and carting materials and employing tradesmen at her own expense, only to be evicted within a year with no compensation: and in the words of the reporter who covered the story: ‘As yet she knows not where to lay her head on the 26th of May.’ How powerfully could personal stories like that impact on visitor experience?

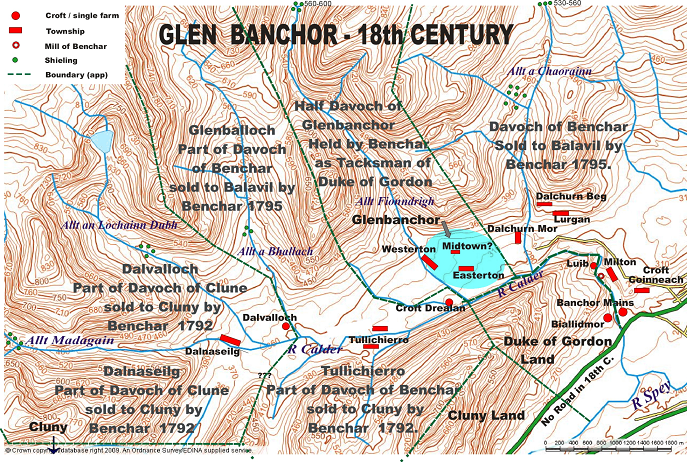

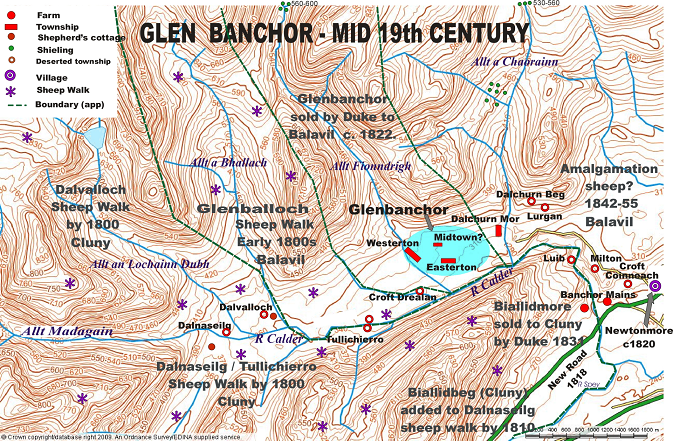

The depopulation of the glen is in itself a microcosm of Highland history. Bankruptcy forced the Banchor Macphersons to sell off parts of the glen in the 1790s, and though such a small geographical entity, Glen Banchor ended up in the hands of three different landowners – the fate of the population depending on which laird they ended up with. The western end, comprising four townships (including Dalnaseilg and Tullichierro), was purchased by Cluny Macpherson, the clan chief, and within a few years had been converted to a sheep walk, leaving the upper reaches of the glen in the hands of two or three shepherds. The area east of the Dalchurn bridge, however, experienced a more gradual depopulation. It had been bought by Macpherson of Balavil, and the four townships there were gradually amalgamated to create a larger more ‘efficient’ unit, eventually being incorporated into the much wealthier farm of Banchor Mains, situated on the more fertile land below the entrance to the glen. By 1871 there was only one elderly female left in the eastern end of the glen – not even a shepherd.

The central portion of the glen between the Allt a Chaorainn and the Allt Fionndrigh, containing three townships, including Glenbanchor itself, was owned by the Duke of Gordon whose tenants were at first protected by his opposition to sheep farming. The Duke’s land here was later sold to Balavil, and though the tenants maintained a degree of security until the 1870s, they would become victims of one of the last of the Highland Clearances in 1876 – an extensively documented clearance yielding much valuable information both on life in the glen and on the nature of the clearance. The new sheep farm was rented at only £3 8s more than the combined crofters’ rent – a chance to engage the visitor in speculation on the motives behind the evictions. It was a time when the wool market was collapsing, but sporting interests were becoming increasingly lucrative – and therein may lie the real reason for the final depopulation. Thus, by 1891 the only working occupants left in the entire glen were two shepherds. Today, even their houses lie in ruins.

Logistics

Heritage trails, of course, are not without problems, not least the risk of damaging the ambience and nature of the very experience you are trying to preserve. It is imperative that any such development be as unobtrusive as possible: no increased vehicular access, no new paths or bridges, just a map or leaflet with key places and summaries provided, a few numbered posts to identify those locations, perhaps a few tasteful information boards at strategic points (though with modern technology this is not actually a necessity). Indeed, an app could guide the walker through such sites with almost no visible impact on the landscape, while providing far more detailed information than information boards could. Leaflets and maps would, of course, need to identify easily accessible walks, with grades of difficulty for remote shieling sites in the hills or where burns need to forded as at the far end of Glen Banchor. The point is not to make it easy, but to allow the more adventurous and interested visitor to explore and appreciate the glen as it is.

The scope for developing ‘open-air’ cultural heritage is obviously huge, and within the CNP there are surely many such localised historical experiences (just a few miles away, for instance, Glen Feshie has a totally different depopulation experience involving a substantial chain migration to Canada). There is a fascinating story to tell – not without economic potential for local communities – and it would also prove a great facility for local schools to enhance their heritage curriculum. Finally, it would provide an excellent opportunity for a co-operative partnership between the CNPA, the estates and local heritage groups.

Post-script – example of existing interpretation in National Park supplied by reader

Very Interesting and informative post from David Taylor on Glen Banchor. I couldn’t agree more that better interpretation is needed – including a focus on our Cultural Heritage. Above, as postscript to main article, is the main CNPA interpretation board at Drumochtor Pass which we cycled past on Saturday – surely they can do better than this!

An interesting article David and if you could get in touch with me at the Cairngorms National Park Authority we’ll have lots to talk about – we’ve just started a three year project in partnership with local communities in Badenoch (funded by HLF, Transport Scotland, HIE the Highland Council and others) and that has great oportunities to achieve many of the things that you talk about.

And we’ll try and get that sign on the A9 seen to too.

Thanks

Murray (Ferguson)

An excellent piece

Ditto Strathspey, people and place forgotten or neglected by CNPA . Old

Military Road by Caulfeild , rebranded ‘Snow Road’ , traditional view points ‘enhanced’ with modern art. What about a traditional view marker chart to tell the onlooker what they’re looking at?