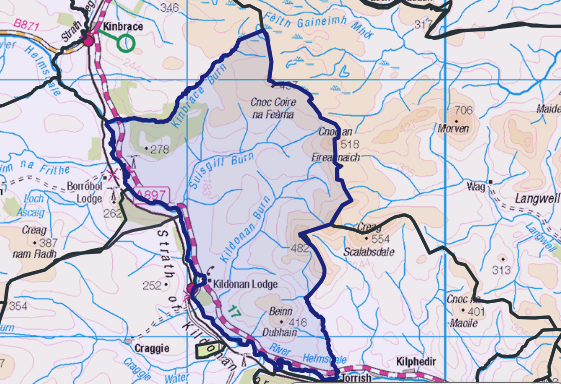

The judgement of the Supreme Court in the Dartmoor camping case issued last week (see here) was good news for those concerned it might lead to the further erosion of access rights in Scotland. Alexander and Diana Darwall, the owners of the 1,619-hectare (4,000-acre) Blachford estate on Dartmoor where they were trying to stop people “wild camping, also owned the Suisgill Estate in Sutherland where they had tried to stop recreational gold panning (see here).

The focus of the case was about the meaning and scope of the term “open-air recreation” under the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 but had far wider implications. Section 10(1) of that Act states:

“Subject to the provisions of this Act and compliance with all rules, regulations or byelaws relating to the commons and for the time being in force, the public shall have a right of access to the commons on foot and on horseback for the purpose of open-air recreation; and a person who enters on the commons for that purpose without breaking or damaging any wall, fence, hedge, gate or other thing, or who is on the commons for that purpose having so entered, shall not be treated as a trespasser on the commons or incur any other liability by reason only of so entering or being on the commons.”

Mr and Mrs Darwall contested that the term “open-air recreation” did not include (in the words of their lordships) “what is known as wild camping (ie camping in areas other than designated camping sites)”.

The case started at the High Court, where the judge agreed with the Darwalls, but the Dartmoor National Park Authority then appealed to the Court of Appeal, which overturned the decision (see here). Only people as rich as the Darwalls could then have taken the case to the Supreme Court which ultimately decides the civil law across the UK. The Supreme Court has now dismissed the Darwalls’ appeal, finding that Section 10 (1) of the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 “confers a right of public access which includes wild camping” (extract from the very useful three page press summary of the case (see here).

The judgement has implications not just for the right to camp on Dartmoor but what activities are included in access rights across the various jurisdictions in the UK including National Parks.

The Supreme Court judgement – the meaning of “Open-air recreation”

The judgement starts with the important statement that “In our view, as a matter of ordinary language, camping is a form of “open-air recreation”.

The judges then apply that reasoning to the meaning of Section 10 (1) of the Dartmoor Commons Act:

“The words “on foot and on horseback” in section 10(1) describe the means by which the public are to have a right to gain access to the commons. They do not qualify the words which follow which describe what that right is given for: “for the purpose of open-air recreation”. Those words state in general terms according to their ordinary meaning the purpose for which access to the Commons may be had by those means. Accordingly, we do not accept the submission of Mr Morshead for the appellants that the open-air recreation in question can only be in forms which are pursued by proceeding on foot or on horseback so that, for example, one would have no right to stop to have a picnic. Having a picnic is an obvious form of open-air recreation, as are birdwatching, sketching the landscape, flying a kite, walking a dog, having a family game of kick-the-can (examples referred to by Underhill LJ at para 65 of the Court of Appeal’s decision). In our view, in line with the observations by Underhill LJ at para 65, it would be absurd to construe section 10(1) as not including a right to carry on such an activity. We agree with Underhill LJ at para 65 that Parliament cannot have intended this. The same reasoning applies in relation to the open-air recreational activity of camping.” [My emphases]

(Elsewhere in the judgement the Supreme Court notes that rock climbing provides another example of open-air recreation).

It is important to highlight here that the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 does not create a statutory right of access by means of bicycle or boat, only by foot or by horse, so the “means of access” given statutory protection on Dartmoor are significantly more limited than those provided for under access rights in Scotland.

The Supreme Court judgement then follows through these points about the ordinary language meaning of open-air recreation by explaining the links of the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 to the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. The 1949 Act also refers to the public having access for “open-air recreation”. The Supreme Court judgement then describes how both Acts include provisions to exclude certain means of access (eg by motor vehicle) and to regulate (or ban) certain activities through the creation of byelaws. The judges concluded from this that if an activity is NOT specifically excluded from the ordinary language meaning of open-air recreation under the provisions of the two Acts, it should be included. Hence why they found that, subject to any regulation through byelaws, the 1985 Act provides for a statutory right to camp on Dartmoor.

The Supreme Court reinforces this argument by also finding that “promoting enjoyment by the public of areas designated as National Parks, was open-ended and again supports a wide conception of the notion of recreation to be engaged in there by the public”.

Implications of the Supreme Court judgement for Scotland

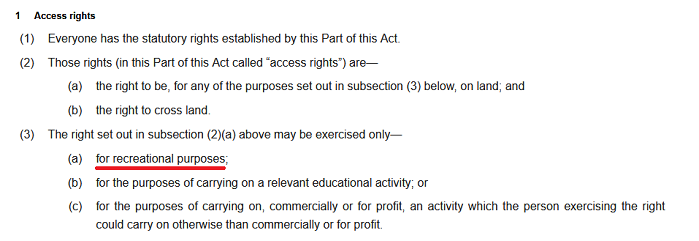

While the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 does not use the term “open-air recreation” it does refer to “recreation” in its first clause:

While the 2003 Act does not define what is meant by “recreational purposes”, its meaning has always been taken to be open-ended and that as a consequence access rights have been taken to encompass a wide range of activities, just as the Supreme Court has decided for “open-air recreation”. Those activities include camping and having a campfire/barbecue but also “means of access” like cycling and boating.

Had the Darwalls won their case at the Supreme Court, that interpretation of the “recreational purposes” included under access rights in Scotland could have been opened up to legal challenge, perhaps from the Darwalls on their estate at Suisgill. The primary importance of the judgement therefore is it adds legal weight to interpretations of what should be included in access rights. Its implications, however, are wider than that both for camping and access rights more generally.

First, there has been a lack of clarity about the meaning of “wild camping”, a term that was not used in the 2003 Act but is used in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (SOAC) when it states “Access rights extend to wild camping”. Some people/organisations have tried to use this to argue that legally there is a legally a difference between roadside camping and wild camping, with access rights only really applying to the latter. That argument was used by the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA):to help justify the introduction of the camping byelaws there:

“Many of those who responded in objection to the proposals [to introduce the camping byelaws] considered them to be an unacceptable infringement of access rights under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. These comments are considered to overlook the fact that the activities that are being managed (largely car-borne camping) do not fall within access rights”. (Para 3.12 of Board Paper on the Your Park proposals that led to the introduction of the camping byelaws). Hence the importance of the Supreme Court referring to “what is known as wild camping (ie camping in areas other than designated camping sites)”. Under their interpretation “wild camping” would cover any “roadside camping” on the Dartmoor Commons and, by extension, the LLTNPA was completely wrong to make this particular claim.

In fact, both the SOAC and NatureScot’s excellent Guidance on “The management of camping with tents in Scotland” (see here) make it reasonably clear that camping rights extend to all areas covered by access rights, its just in order to exercise those rights responsibly you should try to avoid camping in certain places (like close to houses). That interpretation of the law, which I have long argued on parkswatch (see here), should be reinforced by what the Supreme Court said in their judgement.

Moreover, the statutory duty under the National Parks (Scotland) Act 2000 for National Park Authorities to promote public enjoyment of outdoor recreation, which the Supreme Court says includes camping, by implication means they have a duty to promote the right to camp – the opposite of what they have been doing!

Second, the deliberations of the Supreme Court have implications for messages like “Keep to the path where possible” which have been supported by bodies like the Cairngorms National Park Authority (see here for example). Under the same logic that led the Supreme Court to conclude that under the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 “it would be absurd to construe section 10(1) as not including a right to carry on such an activity” (picnicking etc) it is also absurd to believe that messages to keep to the path are compatible with all the activities that are cover by access rights in Scotland but take place “off path”.

In fact, as I have explained previously, central to the negotiations about access rights in Scotland was that while most people use paths most of the time, the right to move away from the path whether to swim, watch wildlife or have a picnic was central to the right to roam – to suggest otherwise, as the Cairngorms National Park Authority has done, is irresponsible. I hope that if they persist in issuing such messages they will now be challenged legally.

The contrast between how our National Park Authorities in Scotland have failed to stand up for access rights and with how the Dartmoor National Park Authority (supported by the Open Spaces Society) has been prepared to take its defence of the right to camp under the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 is striking.

The representation of the public interest in the Dartmoor camping case

It is also worth noting the very important comments the Supreme Court made about “the nature of the relief sought” (i.e a declaration that Section 10 (1) of the 1985 Act did not include the right to camp) “and the procedure used”. The Supreme Court found that:

“as the appellants were seeking to restrict the interests of the public then the Attorney General ought to have been joined as defendant in the proceedings in addition to DNPA given that no authorised government department is identified clearly as the appropriate defendant: see section 17 of the Crown Proceedings Act 1947. When joined as a party, it would have been a matter for the Attorney General to decide what part to play in the proceedings. For instance, the Attorney General may have decided to leave the defence of the proceedings to DNPA. However, even if the Attorney General decided to take no active role in the proceedings the Attorney General would still have remained a party to the proceedings. It was only if the Attorney General was a party to the proceedings that a declaration could be made binding the public.”

That could have implications for any challenges in future by the likes of the Darwalls to the scope of access rights in Scotland. The Lord Advocate may have to get involved rather than leaving underfunded access authorities to fight cases themselves. In that respect it is worth noting that the current President of the Supreme Court, who sat on the Dartmoor camping case, is Lord Reed, a Scottish judge and an expert on the defence of human rights.