If you have not seen it and care about either conservation or outdoor recreation you should watch this video which was added to the Cairngorms Capercaillie Project facebook page on 11th April (see here). In it, two birders who had come from England to view capercaillie, confess the error of their ways after being spoken to by the Capercaillie Project and the police and vow “never ever to look for a capercaillie from March up to pretty much September”.

If you have not seen it and care about either conservation or outdoor recreation you should watch this video which was added to the Cairngorms Capercaillie Project facebook page on 11th April (see here). In it, two birders who had come from England to view capercaillie, confess the error of their ways after being spoken to by the Capercaillie Project and the police and vow “never ever to look for a capercaillie from March up to pretty much September”.

What’s wrong about the video

Why would anyone “spoken to by Rangers and the Police” agree to be filmed (a few thousand people have viewed the video to date), an action that could potentially destroy their reputations and put them at risk of verbal abuse or worse? The apparent answer was on twitter:

It looks from this as though the two appear to have judged the risks associated with being filmed as being less than that of the police taking “further action”, though whether they were told this by the police or rangers is unclear.

While it is now fairly standard for people accused of driving offences to be offered the option of attending a training course (being educated) instead of being given penalty points, if the choice was between being filmed and being issued penalty points that would have significant implications for civil liberties. In filming the men, therefore, and referring to the police intervention it seems to me the Capercaillie Project are on very dangerous/legally questionable ground, which risks subverting basic legal protections and replacing these with something that resembles a show trial.

The need to respect legal processes and civil liberties would not prevent the Capercaillie Project – or anyone else for that matter – issuing videos which feature members of the public calling on others to follow their example. In fact, one of the best ways for example of influence the public is to get people with similar interests talking to each other. It is a good idea to get birders who want to get that capercaillie “tick” but might not be aware of the potential consequences to talk to other birders.

This, however, needs to be on an entirely voluntary basis and certainly not following police involvement. The Capercaillie Project’s reference to the police not only reveals the unsavoury way in which this video came about, it suggests that they are keen not just to educate other birders but intimidate them too, with the implication if the “voluntary” advice is not followed, charges might follow.

The law and capercaillie

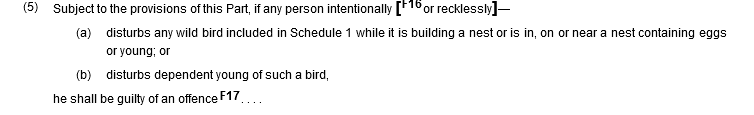

If the two men were threatened with further action, that action was most likely being charged under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, as happened to a birder last year (see here). The Act makes it an offence intentionally or recklessly to disturb the nest or young of a Schedule I species:

Capercaillie were not originally on Schedule 1 but were added in 2001, after a voluntary ban on shooting them in the 1990s. Soon afterwards were granted further protection by the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. This added a provision that “any person who intentionally or recklessly disturbs any wild bird included in Schedule 1 which leks while it is doing so shall be guilty of an offence”.

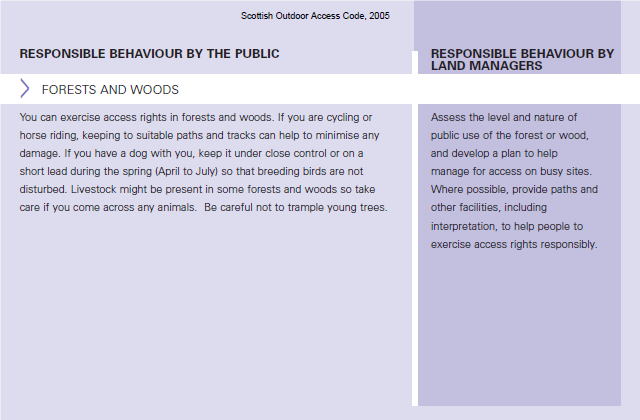

The key word in the law is “disturb”. The offence is to disturb a Schedule 1 bird and not, for example, to watch one. That is made clear in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (SOAC):

“Watching and recording wildlife is a popular activity and falls within access rights………….Take extra care not to disturb the wildlife you are watching” (Page 115).

Even where a person or group of people hurry through the pinewoods looking for a capercaillie lek, nest or young, in a way that is likely to cause disturbance, that does not mean disturbance has taken place. There have to be capercaillie present for a start and then there needs to be some proof they have actually been disturbed (e.g. adult birds disperse from a lek, a hen leaves the nest, young scatter).

Then there is the qualification in the law, the disturbance has to be “intentional” or “reckless”. A birder searching for capercaillie is acting intentionally and, even though the person might not be intending to disturb the bird only to watch it, it might well be that the courts would regard any disturbance resulting from that as intentional. But where a person has gone out for recreation, has no interest in capercaillie and accidentally comes across a lek, nest or young, it is difficult to see how any disturbance could be regarded as intentional.

There is, however, a grey area in the law where a person is alerted during the course of their recreation that there are capercaillie in the area AND they could cause disturbance. If that person then chooses to carry on with that activity should any disturbance that results from that be caused be regarded as intentional? The answer is likely to be “it depends”. If a person ignores a sign that says there is a lek on the path, continues along it and causes disturbance, the courts might well regard any disturbance as intentional. But what if the sign tells people there are capercaillie or black grouse in a large area of forest, like Kinveachy say or Rothiemurchus, where the chances of any individual coming across a capercaillie or black grouse, let alone disturbing them is very low? If that individual then has the misfortune to disturb capercaillie or black grouse, should the courts regard that as accidental or intentional?

The Scottish Outdoor Access Code (SOAC) and capercaillie

The legal rights of access introduced by the Land Reform Act in 2003 were built around the fact that other laws that had been developed to control irresponsible behaviour in the countryside and were regarded as fit for purpose. Throughout SOAC, the statutory guide about how to exercise and manage those rights responsibly, there are references to the Wildlife and Countryside Act and its provisions. It clearly states that access rights do not extend to “being on or crossing land for the purpose of doing anything which is an offence, such as theft, breach of the peace, nuisance, poaching, allowing a dog to worry livestock, dropping litter, polluting water or disturbing certain wild birds, animals and plants.

SOAC also provides guidance on some of the “grey” areas of the law and what is the responsible thing to do based on further agreements between organisations representing land managers, conservation interests and outdoor recreational interests. While neither capercaillie nor leks are mentioned explicitly, it does contain advice/interpretation of the law relevant to the Capercaillie Project’s video for example:

The capercaillie project – pushing the boundaries of the law?

Until recently most of these questions about the precise meaning and extent of the law in respect of what might constitute recreational disturbance to capercaillie were non-issues but, as their population has continued to fall, the pressure on the project to show it was doing something to save them has increased. Moreover, in raising awareness about the plight of the capercaillie, the Capercaillie Project and the Cairngorms National Park Authority had also made more people want to see them. The conservation paradox is that the best way for the public to value something, is to experience it, but that can then create new pressures which may need to be managed. In the case of capercaillie, specific issues were created with birders, who wanted to see the bird before it became extinct in Scotland again and gravitated towards the area around Carrbridge where conservation activity was most publicised.

Hence the CCTV cameras – the two birders were “recorded” – and “dawn patrols”:

Besides the specific concerns highlighted in this post about how the Capercaillie Project has dealt with the two birders who were “caught”, there are questions about whether this approach to birders was the right one. In the 1950s the RSPB deal very successfully with the conservation paradox as it applied to the osprey that had returned to Scotland by building the viewing hide at Boat of Garten: this enabled hundreds of thousands of people to enjoy the osprey without disturbing them.

Currently, over on Deeside the CNPA are not applying the ‘Lek it be’ mantra and, as part of the Cairngorms Nature Festival have promoted a visit to a black grouse lek this weekend for the sum of £10 (see here). This provides further evidence that watching a lek, in itself, is not illegal. Black grouse leks are, of course, easier to view from a distance than capercaillie leks because they take place in more open areas but alternatively creating a place in the forest where keen birders could see live video footage of leks could satisfy some of the desire to see capercaillie and get that “tick”. The Capercaillie Project does not appear to have done anything to help birders or the public do that.

Instead they appear to be trying to stop any visits by birders. While keeping “capercaillie free from disturbance whilst they’re breeding” is not quite the same thing as keeping their leks and nests or young free from disturbance, as stated in the law, the “advice” from the repentant birders in the video goes well beyond that:

“Changed my mind now from going to have a look on paths on which we are permitted, to now not even coming in the breeding season or around breeding season”.

The birders then mention keeping away until the month of September. This conflicts with the guidance in SOAC on dogs (April till July) and the more recent guidance the Capercaillie Project cites on its own website:

Rather than “do not seek capercaillie away from the path”, the message from the Capercaillie Project video to birders is keep away entirely.

Whether or not the Capercaillie Project patrols were instructed to advise other people out for a walk, run or cycle at dawn to keep away from paths is unclear, but the message in the video has serious implications for access rights in general.

One wonders too what is most likely to cause most disturbance, 20 people out on patrol or the occasional early bird out for a walk?!

What needs to happen?

The funding for the Capercaillie Project runs out next month and it is not clear whether the Cairngorms National Park Authority or anyone else is going to have the resources to run dawn patrols let alone publish videos of repentant birders. Many of the issues raised in this post could, therefore, just disappear along with the Capercaillie Project.

The contents of the video and its publication, however, have implications for access rights which could resurface. It should therefore be considered by the Cairngorms National Park Authority, initially through the Cairngorms Local Outdoor Access Forum and then through engagement with national recreational organisations, to review what lessons could be learned. Both capercaillie and people deserve no less.

I will consider the reasons for the decline in the capercaillie population and other actions being taken to tackle this, including the implications for outdoor recreation, in a further post

You say: “‘Then there is the qualification in the law, the disturbance has to be “intentional” or “reckless’……But where a person has gone out for recreation, has no interest in capercaillie and accidentally comes across a lek, nest or young, it is difficult to see how any disturbance could be regarded as intentional”.

Nick, by dropping the term ‘reckless’, you have changed the terms of the argument. But where a person has been told that their action might disturb… but they carry on regardless (i.e.’recklessly’), then it could be seen to be in breach of the law, surely?

Your omission of ‘reckless’ is either careless or disingenuous. It is certainly significant…

Hi Barrie, there was no intention to change the terms of the argument – the points about intentional stand in their own right – and I focussed on the meaning of the word intentional because in my view intentionality is harder to prove than recklessness (which has no counterpart “unreckless” unlike “unintentional). However, you are right that I should have also considered the meaning of the word reckless and how this fitted my argument.

Your example, that “where a person has been told their action MIGHT (my emphasis) disturb………but carry on regardless (i.e recklessly)” provides a good example from my perspective. The crucial word is “might” which covers many degrees of probably from very low to very high likelihood. My contention is where it comes to disturbance there is a clear difference between someone carrying on after being told there is a capercaillie lek ahead (in which case any disturbance could be seen as both intentional and reckless) and carrying on after being told there are capercaillie somewhere in the forest. I don’t think walking along a track through the forest could be viewed in itself as either intentional or reckless in itself (as suggested by previous advice which requested walkers to keep to tracks). I think though your example misses the most important thing about the word reckless, which is refers to act done without any care or attention. HOW the person walks in a forest with capercaillie makes a big difference: eg there is a difference between walking quietly and walking with a ghetto blast. The word reckless therefore does have a very important role separate from whether any behaviour was intentional.

Nothing new. For years LLTPA have been using the threat of draconian penalties under wildlife laws to exclude boaters from ever increasing areas of Loch Lomond including traditional safe anchorages using the supposed presence of Ospreys as the pretext.

Interestingly the information boards on the Loch Lomond islands mention the presence of Capercaillie despite a strong belief among those who know about such things that there aren’t any – maybe this is to be used at some point to stop landing on the islands which there can be no doubt LLTPA would love to do.

You have to admire the cynicism of whoever wrote those guidelines above in inserting the paragraph claiming that vehicles don’t disturb the Capercaillie while pointing out that only landowners can access the area by vehicle -and no doubt representatives of the Capercaillie Prioject! How very convenient.

I think this post serves to emphasise the difficulty of securing convictions for any wildlife crime, the real ones committed by the shooting industry, and the careless, reckless or indifferent actions of walkers, cyclists, ornithologists and dog owners. It a commonplace (well it is in England) that ignorance of the law is no excuse, especially so amongst birders, and I have say well done those guys for ‘fessing up. When it comes to caper, I would think that dogs running free provide a major source of disturbance to these birds, and other wildlife. Ron Greer posted recently on “Rewilding Scotland” about the elephant in the room viz the tension between unrestricted access and protecting wildlife. I do believe that Scotland’s precious access legislation did not give enough thought to wildlife disturbance. Even discussing setting aside an area for nature, and excluding recreational humans, leads to immediate objections.

Hi Phil, you are right that dogs out of control are far more likely to disturb capercaillie than humans but I disagree about those guys fessing up. It appears to have been done under duress/threats and that should be totally unacceptable. It would have been much better for the capercaillie project to get keen birders or scientists saying why they are now staying away from capercaillie (there is a debate about whether those tracking capercaillie should be using dogs to search out nests). The potential for that is illustrated by this local wildlife guide from Carrbridge who has stopped tours to black grouse leks because of concerns about disturbance within the context of a falling population (like capercaillie). Maybe the Capercaillie Project could have got him to explain why on a video even though that might have caused some embarrassment to the CNPA who last weekend were running a tour to a lek on Deeside?

They won’t be staying away from them. As seen in the article, they will make up reasons why their activities don’t disturb the birds but yours do. Restrictions are for you, not for them. Sound familiar?

On the point about using dogs, I did know someone when I was involved in breeding bird surveys who used a well trained pointer. Wonderful to watch, I am not a doggie person, but think this would be a least intrusive way of safely finding nests. Yes, I think wildlife guides should most definitely be keeping their distance, if not staying away altogether. Whatever one tells clients, the word about locations will get out and spread . Some more public info videos by respected ornithologists (Roy Dennis) or even Attenborough about staying away in the spring, come and look for them in the autumn may do some good. Doggie persons probably more difficult to persuade to stay away. But not feeling optimistic for them. Maybe they are doomed again?

That tension between free access and conserving any wildlife can a least be reduced by providing good paths. The wonderful path up Ben Lomond is a good example. It encourages the large numbers of visitors never to stray off it and gives flora and fauna a chance to survive in a busy area. We have lost any sense of wilderness but we might hope to keep some wildlife.

Not a comment on the published video, more a wider one on what seems to be policy challenges around access and conservation goals. Parks and protected areas managers are generally charged with mitigating ecological changes and, simultaneously, providing visitors with opportunities for high quality recreation and education experiences. Hammitt in his 2015 book Wildland Recreation: Ecology and Management – suggests that this inevitably leads to some level of ecological change. Levels of published research on interactions between Access and Conservation management goals are growing and are considering factors such as (a) when and where recreation begins or ceases to affect wildlife (b) levels of visitor use and visitor behaviour impacts on wildlife capacities (c) relative effects of other land use practices. Implementing ecological prescriptions are not easy socio – political calls to make in protected areas the Tyrol or the Cairn Gorms – Spain or Scotland.

A quick sample of recent published research with interesting conclusions includes:

2023 Ecological impacts of (electrically assisted) mountain biking https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/global-ecology-and-conservation

Interesting comparisons of mean speeds, distance travelled, use of single track etc when ebike use compared with conventional bikes. E bikes faster, further. Alpine huts removing ebike chargers!

2023 “If we really disturbed them, they would leave”: Mountain sports participants and wildlife disturbance in the northern French Alps https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-outdoor-recreation-and-tourism

Shows that respondents who witnessed disturbance, such as flight response from wildlife, are much more likely to state that they might be a source of disturbance. Suggests showing video of disturbance response from wildlife online.

Recommends training of mountain professionals (mountain guides, ski instructors, mountain leaders etc.) absolutely needs to be reinforced with courses on the ecology and biodiversity of mountain ecosystems.

2021 Recreation effects on wildlife: a review of potential quantitative thresholds

https://natureconservation.pensoft.net/article/63270/

53 of 330 articles identified a quantitative threshold where disturbance occurred. (i.e. the distance at which wildlife began to move due to a human disturbance).Hiking-only recreation had the lowest median threshold distance from trails for both birds (45 m) and mammals (40 m) but raptors +400m

2020 Assessing conflicts between winter recreational activities and grouse species

In the Tyrol – ski mountaineering activities affected 10.3% of the distribution area of black grouse and 8.6% of the distribution area of capercaillie.https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-environmental-management

2019 Holidays? Not for all. Eagles have larger home ranges on holidays as a consequence of human disturbance https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/biological-conservation

Evidence suggesting eagles have to hunt over wider areas during holidays/weekends when more people are on the hills. Stop start nature of birdwatchers and hunters and off trail walkers more disruptive than regular trail use

2017 Outdoor Recreation causes effective habitat reduction in capercaillie: a major threat for geographically restricted populations Journal of Avian Biology 48.

Recreation in forests with more dense path and track network significantly reduces available habitats.

Thanks Duncan, I was going to take a look at the research on people and capercaillie in a further post but I am very sceptical of much of this research based on my own experience. Over 25 years ago I was in Tasmanin and was suprised when I sat down for lunch while walking that certain species of eagle, not golden, would circle not far above our heads. In fact there were raptors everywhere in Australia. So why would raptors in the UK be so wary of humans but not in Australia. Actually, I think its all about natural selection and raptor persecution and has little or nothing to do with outdoor recreation. Raptors in the UK that come too close to people end up getting shot, as all the data that is being collected shows, so that selects eagles that are wary of people. I was on Mull last year walking along the coast and we spotted three golden eagles ahead, they came closer and closer until right over our heads and seemed totally unconcerned. That behaviour can be explained by the fact that Mull is something of the raptor capital of Scotland where raptors are valued for their contribution to tourism etc; it is not long just wary eagles that survive, hence why they are easy to see. That fits the historical records: there were raptors everywhere in the glens when they were well populated.

Nick thanks. Like you I have had similar eagle experiences and stood on busy road sides in British Columbia to photograph ospreys on nest poles just a few tens of metres away, watched black kites feeding in urban towns in Australia, eagles in Tasmania too and even at home watched red kites circle over the garden. Clearly some species can adapt. Equally I have seen caper explode out of trees when passing and waders and waterfowl lift off shores and lochs when people appear. A dissertation years ago involved me lying up on a hillside in Kintail for days on end with a telescope studying the behaviour of feral goats. It was evident other wildlife I noticed – otters, raptors etc moved on when people appeared – mostly folk didn’t appear to see them. In another study on Creag Megaidh I asked people if they had see wildlife – many said no, although observations from afar showed wildlife on the move in front of them. Eagles probably feel safer in the air even if they are flying overhead than stationary on a perch. I guess flying takes up more energy than sitting around.