On 20th December 2022, four and a half years after the Drumlean Case (see here), Lord Carloway and two other of Scotland’s most senior judges issued another judgement in the Court of Session (see here) which described access rights as “the right to roam”:

“[1] The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 introduced new rights of public access to land. The new right comprises the right to be on land for recreational, educational and non-commercial purposes, and the right to cross land (s 1). This is known as the right to roam (see Anstalt v Loch Lomond & Trossachs National Park 2018 SC 406) [the Drumlean Case]. Access rights are restricted or prevented on specified parts of land; for example, land upon which a building is erected (s 6).

[2] Local and National Park authorities must uphold access rights (s 13). That includes devising a system of “core paths” to give the public reasonable access throughout their area (s 17). This is in addition to the general right to roam, which applies to many more paths and areas.

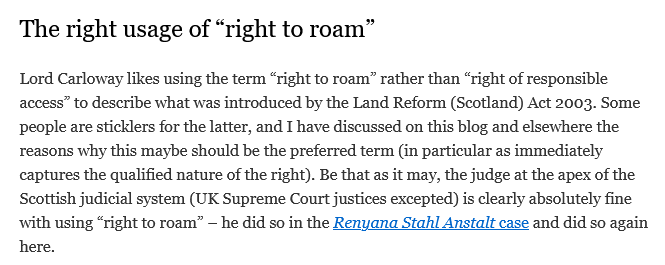

There was no mention of a “right of responsible access”, something which one of the proponents of that term grudgingly admitted on his blog (see here):

This post explains why Lord Carloway uses the term right to roam and what is wrong legally with the term “right of responsible access”. A further post will explain why it poses a threat to access rights.

The law

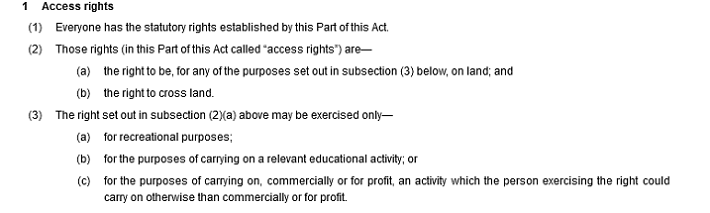

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 – whose 20th anniversary will be celebrated in a couple of weeks – secured and strengthened the customary freedom to roam in Scotland by establishing new statutory access rights:

The wording is important. Those rights are explicitly called “access rights”, not a “right of responsible access”.

Clause 1 sets out the two main qualifications to those access rights. The first is the right to be on (rather than cross) land must be exercised for one of the three purposes set out in sub-clause 3. The second is the reference in sub-clause to land which is excluded from access rights under section 6 of the Act:

![]()

That’s it. There is NO mention of responsibility in the foundational clause of the Act. What it says is that everyone who lives or visits Scotland has access rights, created by statute, not a “right of responsible access”. These access rights are what are commonly referred to as the right to roam, as acknowledged by Lord Carloway in his two judgements.

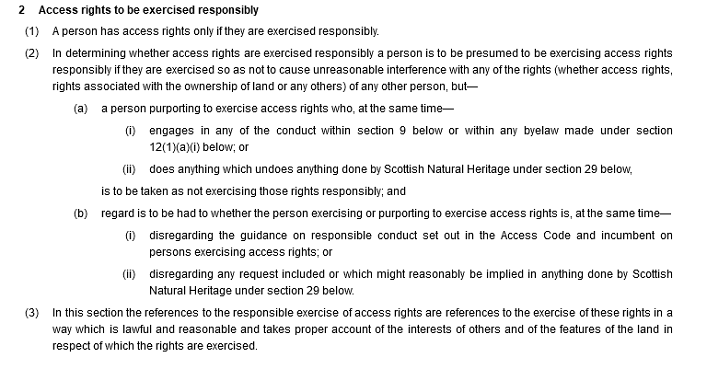

These access rights are then linked to two sets of responsibilities in Clauses 2 and 3, the first for members of the general public, the second for landowners:

, It is this clause that authors like Malcolm Combe have used to argue that the right of access is qualified and would be better described as a “right of responsible access”. However, the emphasis in “Access rights to be exercised responsibly” puts access rights first, responsibility second. The claim this means the same as “a right of responsible access” switches the emphasis and puts responsibility first. It also cuts out the use of the word “exercise”, which is integral to the meaning of the law and used three times in sub-clause 3. A person exercises their access rights responsibly if they do so in a way that is a) lawful, b) reasonable, c) takes proper account of the interests of others and d) take proper account of the features of the land. That cannot be subsumed under the term “right of responsible access”.

, It is this clause that authors like Malcolm Combe have used to argue that the right of access is qualified and would be better described as a “right of responsible access”. However, the emphasis in “Access rights to be exercised responsibly” puts access rights first, responsibility second. The claim this means the same as “a right of responsible access” switches the emphasis and puts responsibility first. It also cuts out the use of the word “exercise”, which is integral to the meaning of the law and used three times in sub-clause 3. A person exercises their access rights responsibly if they do so in a way that is a) lawful, b) reasonable, c) takes proper account of the interests of others and d) take proper account of the features of the land. That cannot be subsumed under the term “right of responsible access”.

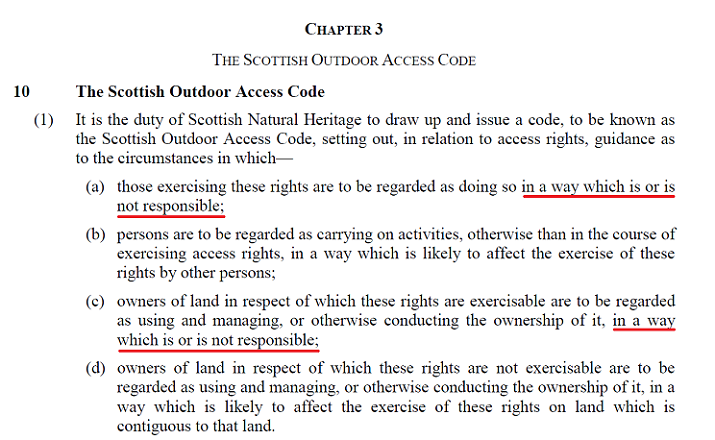

While the word “responsible” appears 14 times in the Act, the term “responsible access” is used not once, not even in Section 10 which required Scottish Natural Heritage to produce the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (SOAC):

While the term “responsible access” crept into the SOAC (mea culpa I was on the Board of SNH at the time it was developing the Code), it is only used four times. Two of those relate to landowners (e.g. where a landowner wants to promote responsible access). The term “responsible access” was therefore invented after the passing of Act and has since been developed further into “a right of responsible access”. Neither term reflects the law.

What is also important to note are the consequences of someone on land failing to exercise their access rights responsibly. They may then lose the statutory protection afforded by access rights – their legal right to be on land for stated purposes or to cross it – but their legal position then reverts to what it was before the Act was passed. To evict the person from their land a landowner would then have to seek an interdict in the courts, just like on land where access rights don’t apply unless another legal remedy happens to be available.

What this shows is that our statutory access rights are actually very strong. They provide people who want to visit or cross land additional legal security, a right to roam in common parlance. Legally this is completely different to what certain advocates of the “right of responsible access” would have people believe, that access rights are weak.

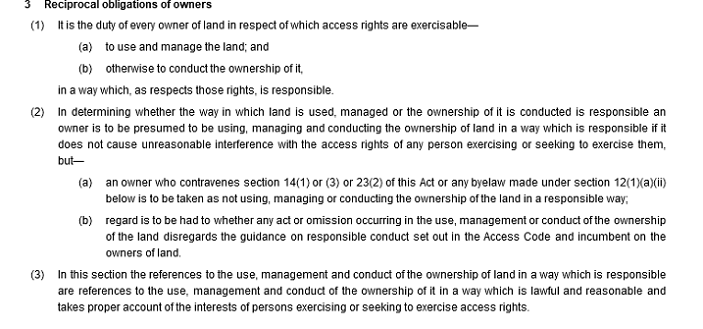

Those who refer to “the right of responsible access” almost never refer to the reciprocal responsibilities of landowners. What is the equivalent phrase for them?

Those who refer to “the right of responsible access” almost never refer to the reciprocal responsibilities of landowners. What is the equivalent phrase for them?

In some ways the obligations on landowners created by the Act could be argued as being stronger than those of the general public, being expressed as a legal duty: “it is the duty of every owner of land…..”). However, sub-clause (3) (above) almost exactly mirrors the provisions placed on the general public (in Clause 2 (3) above). The two clauses interrelate and are mutually supporting; the general public must take account of the interests of landowners and landowners the interests of the general public.

The SOAC reflects this, balancing responsibilities of the public with responsibilities of land-owners. Two sets of responsibilities then, not one as implied by “a right of responsible access”.

What needs to happen?

The correct terminology when referring to the access rights of the general public is therefore “the right of access” or “the right to roam” and this applies over most land or water in Scotland. These are the terms that should be used by all public bodies in Scotland and any other organisations with an interest in access rights.

After my post on what is wrong with the term “access takers” I wrote to the National Access Forum asking them to discuss its use. Early in the New Year to receive a reply from Don Milton, the Convener (who also convener of the LLTNPA LAF). He has committed to discussing the term at the June meeting and meantime said he will recommend those involved in the NAF cease to use it. That is very positive. In the light of the latest endorsement of the term “right to roam” from Lord Carloway and the arguments set out here, I will now ask that the meeting also discusses the term “right of responsible access” with a view to it being removed from the access lexicon for the reasons set out in this post.

Thanks for the post and the link to my own post, albeit I confess I am surprised to be characterised as acknowledging Lord Carloway’s formulation “grudgingly”. If you heard me speaking about this point directly on Out of Doors last year – before this appeal judgment came out – you would, I hope, have heard me sounding pretty relaxed about the matter. There is however little doubt that access rights are not as rock solid as other property rights – another Court of Session judge in an Inner House decision (Tuley) noted the Act’s “reliance on the very protean concepts of acting ‘responsibly’…”, so any commentary from me has, I hope, come from that angle rather than a base objection to what I think can actually be a useful term to aid understanding, and one that I do mention to students in my lectures. Anyway, a more developed version of my blog post on the Gartmore decision itself is coming out in the next issue of the SPEL journal, where I again nod to Lord Carloway’s terminology.

Thanks Malcolm, another nod in the direction of Lord Carloway would be helpful. Not sure I agree about your point about access rights not being as “rock solid as other property rights”. After all the only criminal offence created by the 2003 Act is directed towards the land owner – section 23 makes it a criminal offence for an owner to disturb the surface of a core path or right of way by ploughing etc and then fail to reinstate the surface within 14 days. I await the first prosecution with interest…..

It would be good also if in context of this fresh Dec 2022 reassertion of Legal opinion, a wider discussion might place. I see a real need to refresh the provisions under which a Land Owner or his agent( in the case of forestry operations, sporting pursuits and so on), might seek leave to limit the public’s understanding of the universal right to roam.

Too often across Scotland in the 2020’s the “mumbo jumbo” of ‘risk assessment’ curtails reasonable, open, and free access. Today in a more litigious world – certainly since 2003 – a whole H&S “industry” has become fully established. Prolonged and remote paper exercises can be engaged in by those possessed of an over- stimulated nervous disposition?? perhaps fearful of insurance companies. )

It may appear that to prevent “Right to Roam” it is only necessary that some wilder midnight dreams as Heath and Safety concerns be deployed. (Maybe even self-serving or spurious?) The resultant muddle of where right and wrongs of access may survive, “splashes” right into the middle of the pool of clarity implied by the foundation legislation. A freedom the 2003 Act strived to define in terms of an exercise of mutual respect – a simple application of politeness and ‘common sense’- becomes confused again.

Good work Nick Preserving and promoting the wording and intent of the 2003 Act are essential to maintain our access rights. Any attempt to shift the balance between the responsibilities of the public and landowners must be strenuously resisted or Scotland will end up following England where criminalizing trespass may only be a few steps away.

Usually, when I’ve written about legal matters, I included a disclaimer that I was providing “legal advice.” I’m not legally authorised to do that and I think it’s an offence to pretend otherwise. That said, I think it’s OK to refer people to solicitors and information in the public domain. I think because the wording you refer to has legal status that includes what “responsible” means. A Sheriff may expect people to provide a reasonable account of their actions and intromissions. But that’s not any old reason. They mean it’s got to be legally compliant. Same with “responsible.” You can’t have any old random un-appointed “Sheriffs” dictating to people what that means. They have to comply with the correct legal procedures and the rule of law like everyone else. Fisheries weren’t included in these access rights. The right to fish includes it’s own right of access….for owners or those with permission to fish. About 2013 I took the guys from Alternatives to fish Loch Long at Portincaple. This joker appeared telling anglers they had no right to fish “according to the Access Code.” I told him to eff off and wrote about it in the local press. If you think you’re innocent it’s not a crime and they are not the law. The Sheriff and his men are.

I understand the desire not to be unnecessarily restrictive but to my mind “right to roam” is more restrictive and implies that all that is allowed is to walk from one place to another without stopping or carrying out any other activity which is clearly not the original intent of the Act.

I can’t help feeling though that discussing abstruse semantics is somewhat pointless when the real issue is that whatever you call these rights in theory, in practice they hardly exist. Far from being proactive, many access authorities are not even reactive in any effective way and even contacting them is difficult. There are funded groups which collect information on access issues but do nothing with it which might lead to improvements.

The reality on the ground is obstructed and obliterated rights of way and other paths, heavily fenced fields with one locked gate, clear felled plantations covered in brash and machine ruts and many other issues which mean any supposed right of access is a fantasy, regardless of what it is called.

Even the existence of a core path is no guarantee that it will be reasonably passable, or that it won’t just end at a council boundary because the neighbouring council had a different plan.

Thanks for the post and the link to my own post, albeit I confess I am surprised to be characterised as acknowledging Lord Carloway’s formulation “grudgingly”. If you heard me speaking about this point directly on Out of Doors last year – before this appeal judgment came out – you would, I hope, have heard me sounding pretty relaxed about the matter. There is however little doubt that access rights are not as rock solid as other property rights – another Court of Session judge in an Inner House decision (Tuley) noted the Act’s “reliance on the very protean concepts of acting ‘responsibly’…”, so any commentary from me has, I hope, come from that angle rather than a base objection to what I think can actually be a useful term to aid understanding, and one that I do mention to students in my lectures. Anyway, a more developed version of my blog post on the Gartmore decision itself is coming out in the next issue of the SPEL journal, where I again nod to Lord Carloway’s terminology. [P.S. Sorry if I’ve posted this comment twice – I tried to do it on my smartphone earlier and I don’t know if it worked.]

Well done Parkwatch

A good start to 2023 and more forward looking after the many objects put in front of people since lockdown

The term “right of responsible access” should indeed be banished, but I think the term “right to roam” can be misunderstood, as Niall says, and should best be kept to describe the position in Scotland before the 2003 Act was passed, when that right existed under common law (supposedly). As for now, the Act provides three perfectly clear, uncomplicated terms: since 2003 we have two statutory “access rights”: the “right to be on land” (for limited purposes) and the “right to cross land” – end of story. (As for “access takers”, I suggest “rights holders”. And landowners could be referred to in this context as “duty holders”.)

The position before the 2003 Act is that the public had the “freedom” to access most land and water in Scotland on the basis that a fundamental principle of law in Scotland is that everything is permitted except that which is expressly forbidden by statutory regulation (eg the prohibition on public access across commercial airports). The 2003 Act converted this “freedom” into a “right”. With it came specific duties laid upon various public bodies which helps to safeguard the exercise of these public rights, such as the duty laid upon Scottish Natural Heritage (or Nature Scot as it now calls itself) to produce the Scottish Outdoor Access Code and keep it under review. Other very important duties were laid upon local and national park authorities in relation to the development of core paths and the removal of unreasonable obstructions to access in any places where access rights apply. None of these responsibilities applied to access authorities before 2003 and they would usually only take action to safeguard public access when it involved a claimed right of way. It is therefore very important to understand the difference between a “right” and a “freedom”, with only the former linked to a very useful set of mechanisms for facilitating access or preventing its obstruction. Where rights were not established by the 2003 Act, existing freedoms may still apply. For example access rights for recreational activities do not apply to golf courses, otherwise many people would play golf on those courses without paying. Nevertheless, when I was recently skiing all around my local snow covered golf course I was exercising my “freedom” to do this, not a “right”. In the very unlikely event that the owner objected to this, I would not be able to seek any help from Perth and Kinross Council to deal with this situation as they have no responsibility to safequard this “freedom”. But of course I also knew that the golf course owner could do very little to stop my skiing activity, except by going to court to try (with great difficulty I am sure) to secure an interdict to prevent me returning with my skis. As far as I know no golfers were disturbed by my activity – snow and golf are somewhat incompatible and the golf course owners are entirely relaxed with public use of the course for non golf activities, so long as dogs are under control and any of their mess is immediately removed.

Thanks, Dave, for clarifying this distinction.

I meant to add that there is no “fundamental principle of law in Scotland is that everything is permitted except that which is expressly forbidden by statutory regulation”. I qualified as a Scottish solicitor in 2000, having been taught that assault, theft, murder and breach of the peace are all common law offences in Scotland, not expressly forbidden by statute. That remains the case. I wouldn’t want parkswatch readers to get the wrong idea.

Thanks Ian – I should have also referenced the common law. I was paraphrasing what Lord Reed said in 2000 when he was a Scottish Judge and said that Scotland “is not a country where everything is forbidden except what is expressly permitted: it is a country where everything is permitted except what is expressly forbidden” (Ledingham Chalmers Lecture on “Taking Human Rights Seriously”, June 2000). As Lord Reed today is president of the UK Supreme Court I think we can take this as a pretty authoritative statement. It was referenced in the Scottish Parliament Stage 1 Report of the Justice 2 Committee on the Land Reform (Scotland) Bill and supported in Scottish Parliament debate by Pauline McNeil MSP (Labour), Roseanna Cunningham MSP (SNP) and David McLetchie MSP (Conservative), all of them were qualified lawyers (Official Record, 20 March 2002).

Golf courses are specifically mentioned in the access code. You can exercise access rights to cross a golf course under certain conditions e.g. stay off greens and keep to paths where they exist.

This summer I noticed that Tobermory golf course has signs for walkers at both sides where the access is from surrounding paths but they are subtly different; one says “Please follow these (marked) routes”, the other says “You must follow this route”. The first is sort of OK, the second is not. There is an issue because in places the marked route is unnecessarily circuitous and undulating to take it round the extreme perimeter of the course which is clearly not the intention of the legislation; I will take the direct route in this case and argue that a relevant path does not exist.

I am also picking up who the rights apply to. I’m increasingly working to get permission for education groups to access green spaces, having always been told that education fell into a commercial category, so having different rights. I would be keen to ask the Access Forum to consider the rights of education groups, particularly with a growth in early years and schools using local recreation and nature spaces. Interestingly, there’s one local authority who regularly ask for permission to use public parks…

I’m off to research more

Section 1 (3)(b) of the 2003 Act states that access rights can be exercised “for the purpose of carrying on a relevant educational activity”. Access rights also apply to persons carrying out commercial activities (eg mountain guiding) but these are distinct from educational activities and are covered by section 1(3)(c) of the 2003 Act. You should not therefore be seeking permission to take education groups into green space areas, or virtually any other land or water, unless that particular area is covered by by-laws or local authority management rules that require educational groups to seek permission. I know of no area where such a requirement applies.

Thank you Dave. That had been my understanding for many years working in adventurous, rural settings. My work now is much more urban, and we (along with most others we work with) have taken the ‘be nice – inform them you are coming’. This post has reminded me we need to be more assertive here – that however is a subtle and important change. I have colleagues across other charities, schools and nurseries, local authorities, Forestry Scotland etc I need to discuss this with….

On the other hand there may be a need to consider whether commercial or other organised activities will unduly impact the ability of the general public to enjoy their own activities.

The practice of closing or restricting public facilities for the exclusive use of organised events is increasingly common and unwelcome.

Perhaps the concern over the use of the term responsible access needs a simpler broader look at landuse in general. I recall betting agricultural students to look at this simply and acknowledge that although they would talk about agricultural land as if it was a single use., in fact all landuse is multiple – On land I would use on Deeside as an example they could see that the farms were also used for water catchment and supply, landscape – which was the most economically significant landuse as the basis of the local tourist industry and them of course their is support for biodiversity and the arrival of an emergent landuse like carbon fixation. Landownership is basically the right to use land or dispose of that use. What seems to follow is that since populations using the land for water catchment or tourism using it as landscape are also asserting their right of use – from which you must deduce that, in fact, all land ownership is multiple too. For whatever a party uses the land, farming forestry, water catchment, they are expected and, increasingly, legally required to use it responsibly. I that sense saying that right to roam should be exercised responsible, is it saying little that is significant ? At a deeper level, the access legislation seemed to me to be subtly profound as a way of saying this land is ours in a deeper sense – part of the common weal.

Great post to your usual high standards, Nick – but moving on from your main point you imply in passing that the obligations of land owners are often omitted. I wonder if any work has been done to identify positive examples of land owners and their support for access rights? I note that NatureScot’s web site focusses on “managing access on your land” with many articles on “dealing with issues” of various sorts – they have noting to say about e.g. “the benefits of promoting access”. No wonder access rights always feel under threat when they are always promoted as an “issue to be managed” to land owners! Surely there is a positive business and environmental case that any responsible land owner would want to exploit? If there is, then it should be of interest not just to NatureScot for Scottish Enterprise as well. The right to roam is a Scottish asset, we should exploit it.

Excellent point Andrew. While I am aware of a number of landowners who do strongly support access rights, they tend not to have much “voice” or choose to keep their heads down. I will try and investigate a little further

You could also look into what support they get, if any.

I notice in the Peak District National Park that nearly all the pedestrian field gates are to a standard design, I assume the Park Authority provides these (may even fit them). A properly proactive access authority might do likewise, instead of commissioning yet another glossy report?

A simple stile kit would do wonders for accessibility where fences topped with barbed wire proliferate.

Andrew’s point enters the “murky” area surrounding right to roam that I touched on earlier in this topic. This concerns the responsibility for safety many land Owners their insurers and their agents now claim to observe. Conflicting statutes reveal obligations for the well-being of any person who can claim they were effectively encouraged to enter any space.(not prevented or warned) There are always perceived risks to be encountered while enjoying a right to roam. Any sign to invite surely indicates the land Owner has facilitated access and therefore has a responsibility to provide and maintain safety rails, steps and adequate warning signs.

First the obvious conflicts within the burgeoning body of H&S legislation will need to be addressed. The ‘dead hand’ negativity of the Insurance industry would need to be curtailed?

Tom, there is case law stating that reasonably expected hazards are the responsibility of the access taker, see the cases I cited in my reply to the Radical Road article.

Additionally there may be a useful side effect of the fact that landowners cannot compel anyone to use a particular route where general access routes exist, they can only encourage them to do so e.g. by the provision of gates, stiles etc. (chance would be a fine thing!) This means that people are free to avoid any perceived hazard which may exist. Tobermory Golf Club please note.

I think we walkers need to have some empathy for the smaller farmers. People who are not responsible walkers let their dogs go wild in crops, walk and picnic in cropped fields, leave litter, trample crops, let their dogs go in beside livestock, nosey in farmer’s buildings, cut fences, damage fences, don’t use paths, leave gates open and livestock escape etc. etc. The farmers do not get a moment’s peace despite having paid hundreds of thousands of pounds to buy their farms. I am a responsible walker but I am in the minority, unfortunately.