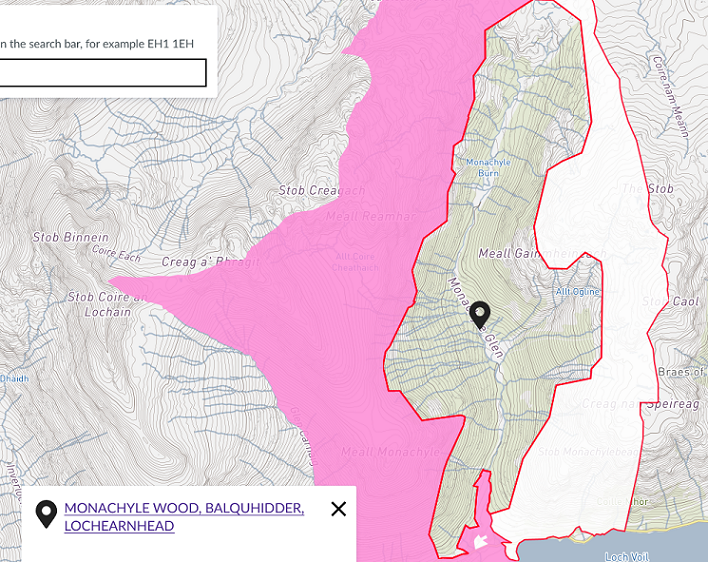

“Monachyle Wood”, at the west end of Loch Voil in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park, is being marketed by John Clegg, part of Strutt and Parker, at offers over £6,250,000 for 621 hectares (see here). The history of this plantation provides a good example of public sector financial mismanagement in favour of private interests also illustrates much else that is wrong about forestry in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park.

History

The lower part of the farms in Monachyle Glen, known as Monachyle Mhor and Monachyle Beg, were bought by the Forestry Commission in 1976. The price is not recorded on the title deeds which I obtained (£3 plus VAT) from the Registers of Scotland.

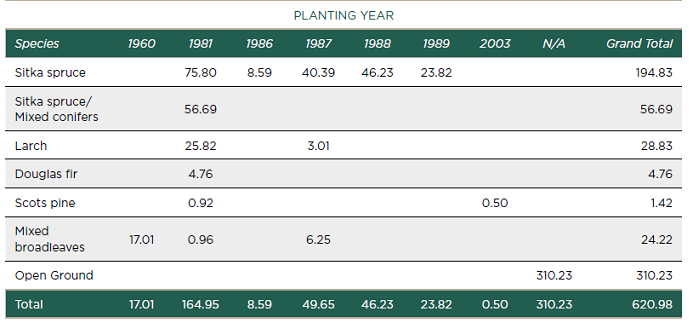

The glen was then planted, mainly with Sitka spruce, in the 1980s:

Scottish Ministers sold Monachyle Glen on 8th August 2016 to Nikolas Rupert Briggs and Katie Jane Sutton for £1,200,000. If the wood sells for the asking price of £6,250,000 , Mr Briggs and Ms Sutton will have made £5 million in just five years.

According to the sales brochure: “the majority of the Sitka is approaching maturity and with an average weighted age of 38, any incoming purchaser would be able to benefit from immediate tax free timber income.”

Forest asset stripping

The national forest estate is now £5m poorer than it might have been had Monachyle not been flogged off for £1,200,000. Spread over the 40 years that Scottish Ministers had been managing the land, that comes to £30,000 a year at current prices. A sum hardly enough to recompense what must of been spent on management annually, let alone the cost of acquiring the land, fencing it and then planting it. Why and how Scottish Ministers decided to sell off a forest nearing maturing for such a knockdown price deserves investigation by the Scottish Parliament.

The sales brochure, however, suggests that Scottish Ministers didn’t neglect the public interest entirely by guarding against the future owner profiteering excessively from the development of a hydro scheme:

” A Standard Security and Clawback Agreement is to be granted by the purchaser in favour of the previous seller, the Scottish Ministers, for claw back of 25% of any uplift in value resulting from any hydro based renewable projects given planning consent. The Standard Security and claw back ends on the 3rd August 2030”.

Given this regard to the future, it is even stranger that Forest Enterprise Scotland failed to consider any likely increase in value from the timber being almost ready to harvest.

The title deeds from the Land Registry described Mr Briggs and Ms Sutton “as partners and trustees for the firm of Evison Farmers, Eloughton Hill Farm, Brough”. While both Mr Briggs and Ms Sutton are listed on the Companies House website, none of the companies for which they are Directors appear to have been involved in this purchase and I can find no company of the name “Evison Farmers”. It is a bit of mystery therefore what “firm” owns the property and, in the absence of accounts, it is not possible to ascertain how much if anything they have spent on managing Monachyle Wood in the last five years.

The current owners do, however, have a Scottish connection even if it is not clear how they raised the money to purchase Monachyle. They were the directors of Bragleenbeg Farm Ltd, a farm at Kilniver near Oban, which was dissolved in 2017 (see here) and are now directors of Bragleenbeg Ltd which succeeded it. According to the accounts till December 2020, that business’s net assets were £80,856 and its main creditors were its directors so it does not appear that they could have used the Bragleenbeg companies to purchase Monachyle. None of the other companies Mr Briggs and Ms Sutton are involved in appear to have any significant assets. How they funded the purchase in 2016 is not clear.

Monachyle is not the only significant part of the national forest estate that has been sold off in the area. A similar size piece of land, Ewich Forest, by Crianlarich was disposed of in 2019/20 for offers over £5.75m (see here). As I commented then, the price was a reflection of the timber being ready for felling, raising further questions about why Monachyle was sold off so cheaply.

Carbon offsetting and the historical mismanagement of the Monachyle Forest

A small part of the explanation for the quintupling of price may lie in the carbon offsetting potential of the parts of the glen which are not planted at present:

“The commercial timber element of Monachyle is supported by the large area of open ground that holds significant potential for carbon sequestration and natural capital opportunities. Extending to approximately 310.23 Ha (766.57 Acres), Monachyle has the potential to sequester up to 33,000 tonnes of carbon (CO2 equivalent) with up to 100 hectares of new woodland creation possible, subject to Scottish Forestry approval.”

The reason for this is that Monachyle Glen has been mismanaged historically and this may have actually increased the potential of the land for carbon off-setting purposes.

Blocks of trees with little or no regeneration beyond the edge of the original planting are a tell-tale sign of overgrazing. Both the Sitka and larch will have produced seed for many years but grazing pressure has been so high that any new conifer saplings get eaten. You can see evidence for this on the left where there are a few smaller conifers and beyond that scattered native trees. When first planted, the fencing round the whole area kept the deer out enabling trees to spread then, once the deer got in, all natural regeneration stopped.

This explanation is confirmed in the sales brochure, which refers to the deer fencing being in “average condition”, i.e not effective, and 27 stags and hinds being shot on the property in 2021. That is 1 deer culled for every 23 ha or four per square kilometre. That in itself would be enough to stop most natural regeneration but suggests the actual deer population is way higher than that. Had deer numbers been kept low, the woodland would have spread and the opportunity to get Scottish Forestry to fund the planting of another 100 ha would not exist.

As a further irony, the land is now being marketed for its “excellent amenity and sporting potential”. The truth is that as well as being in a poor state environmentally, the landscape of Monachyle Glen faces being degraded further by new forest tracks because no account was taken of how timber would eventually be extracted when designing the plantation.

Monachyle Glen wood and the LLTNPA

As I commented back in 2019 (see here) the LLTNPA’s Woodland and Trees Strategy, developed jointly with what are now Scottish Forestry and Forest and Land Scotland, contained not a single meaningful proposal to change how commercial forestry in the National Park would be managed. For example, there were no targets for the conversion of conifer plantations into native woodland. This means that whoever profits from harvesting the publicly planted timber at Monachyle can then repeat the process all over again. Nor does the Strategy contain any meaningful proposals to improve deer control in forests.

Unlike other parts of the world – with the exception of England and Wales – the land in Scotland’s National Parks is not in public ownership. Not only that but our National Parks haven’t prevented public land from being sold off on the cheap, whether as in this case or Scottish Enterprise’s agreement to sell the Riverside Site at Balloch to Flamingo Land. Instead of using their ownership of land within our National Parks to improve how it was managed and influence neighbouring private land-owners, up until last year Scottish Ministers were selling off land to balance budgets and any acquisitions had to be balanced by new sales.

Then last year Forest and Land Scotland launched a new acquisitions strategy (see here) which included a new Low Carbon Investment Fund that:

“will principally be funded from at least £30m allocated by Scottish Ministers to Forestry and Land Scotland to be invested during the period 2021-2026 for enhancing the national forest and land in response to the climate emergency”.

While a welcome change in policy direction, with land prices rocketing this is unlikely to change much. The public sector has moved from selling cheap to buying expensive. Once again the main beneficiaries of this are likely to be private interests, the Mr Briggs and Ms Suttons of this world.

In Scotland we should be aiming to gradually increase the proportion of land in our National Parks that is owned by the state and by environmental organisations. That means there should be a policy presumption against any further public land sales, with the exception of transfers to local community ownership. But we also need a system where our National Park Authorities have a statutory right to intervene and set conditions on the sale of land, apart from people’s houses and small-holdings, in our National Parks.

Such a system would provide an additional safeguard against public authorities like Forestry and Land Scotland and Scottish Enterprise selling off any further land. It would also would allow all new owners, including those who claim to be buying for carbon off-setting purposes but who in reality are mainly interested in hoovering up public money in the form of grants, to be vetted to determine what they are prepared to invest in land-management and whether this will promote the public interest in our National Parks.

Sorry I just don’t get why do we have to turn every area of land to scrub and tree cover. It’s a good job the deer can keep some areas clear. A great article in the Killin News talks about the same issues. When I was growing up we used to see big herds of deer on the hillside around Crianlarich. Now they are hardly seen except if they have been killed on the road. As I have said before far more species of wild life and flowers were around years gone by. My dad kept bees that thrived because there were plenty of flowers, heather etc to collect pollen and nectar from. Very little heather exists in sufficient areas now. The health of the heather hillsides is at risk even more now that the maintenance using controlled burning is being stopped and the areas covered in so called the required trees. The burning of the heather has actually been proved to be helpful in carbon protection by several universities.