The divurgence between how people in Glasgow have welcome people to the COP -26 summit has been been most interesting. On the one hand sections of the population profiteering through exorbitant charges for accommodation – one wonders if any of the hotels or landlords charging delegates £1000s to stay will invest those profits in making their accommodation neutral? On the other hand hundreds of people hosting strangers for free through the human hotel (see here). One hopes that the friendships made will be worth far more than money. But the media still reported that 3000 visitors were still left with nowhere to stay.

Last Thursday I went to speak to people at the Extinction Rebellion camp in Pollok Park. The camp is not a protest but it is for protesters; for people needing somewhere to stay in order to protest. The people who organised it didn’t ask, that would have probably invited the usual reflexive bureaucratic “no”, but they did arrange their own toilets (those in Pollok Park, not so long ago European Park of the year, have now been closed for 18 months).

The legal position

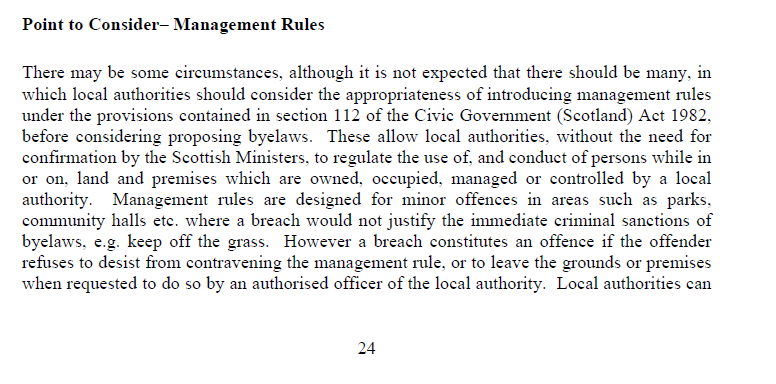

While creating a right of access, the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 allowed public authorities to continue to exercise their powers under the Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982 to regulate behaviour in public places through what are known as management rules. Advice about their use was included in the Guidance to Local Authorities and National Park Authorities issued in 2005 (see here)

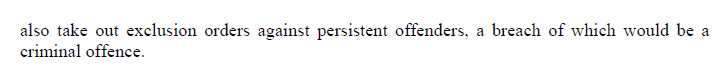

Management rules are in place for Pollok Park (see here) and contain provisions for camping:

Since the people who organised the camp hadn’t asked and not received written consent for the camp they were in breach of the management rules. The remedies available to Glasgow City Council under the Civic Government Act (see here) would have been to try and expel the campers under clause 116 or seek an exclusion order 117.

Breach of management rules, unlike breach of byelaws, is not a criminal matter and therefore generally outwith the remit of the police. So, despite the presence of 10,000 police in Glasgow, had the City Council wanted to expel the campers they would have had to ask their own staff to do so. As for seeking an Exclusion Order, breach of which would constitute a legal offence, two weeks notice has to be served on a named person, by which time the COP summit would be over and the campers gone.

The important point here is that even where access rights have been modified by management rules, the law is based on tolerance and respect for civil liberties. Where people are occupying land for a temporary period and doing no harm, the law allows them to stay for a temporary period. That is a good thing and should be celebrated across Scotland. It is also a reason why the camping byelaws in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA), which are unique in Scotland, are so wrong.

If anyone tried to set up a temporary camp, even with their own toilets, anywhere in the LLTNPA’s camping management zones between March and September they would be committing a criminal offence. As such they could be – and indeed have been – removed by the police.

The response of Glasgow City Council

Glasgow City Council (GCC) officials appear to have exercised a degree of common sense at Pollok Park. According to the campers I spoke to they had been visited by various officials culminating in a visit from “the boss”. When GCC staff saw that people were camping responsibly – the campers had brought a large metal fire tray besides the toilets – they agreed they could stay, pointed them to an outdoor tap 800m away and agreed to provide bins for the site. That might not be much but is far more than the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority has ever done in its camping permit areas.

What this shows is there are people in public authorities who still want to help people and its to the credit of senior management in the City Council that they have allowed them to do so.

The help those staff have been able to provide however, is very limited and will hardly cost a penny. One wonders what would have happened if the campers had not arranged their own toilets? Would the Council have re-opened the toilets in Pollok Park which have been closed for the last 18 months? I have my doubts that frontline staff would have been allowed to do the right thing.

The cost of the policing operation for COP-26 has been phenomenal. Reputedly 10,000 police, brought in from all over the UK, and their accommodation for two weeks. It’s no wonder that visitors wanting to come to Glasgow for the COP summit have found it so hard to find anywhere to stay.

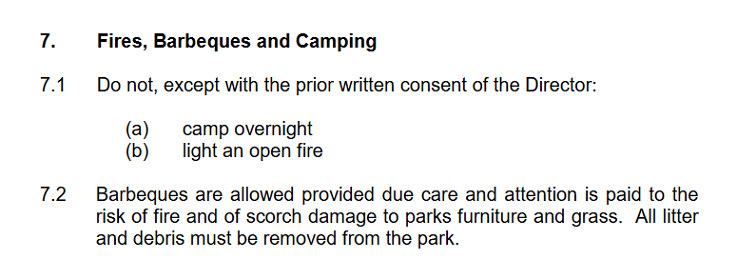

In this situation, instead of trying to help visitors, including those who wanted to exercise their right to protest, Glasgow City Council left it to the “market” and did nothing. They could, without very much trouble or cost, have set aside areas within a number of City Council parks for people to camp or park up caravans or campervans and provided toilets and taps. That would have cost a whole lot less than the amount that it cost to “defend” the City Chambers for a day.

More radically, GCC could have made public buildings available to ordinary people during the COP summit, but there wasn’t even a facility for marchers to use the toilets in the City Chambers on the day of the march. Instead, rows of police.

This illustrates that the failed approaches to visitor management in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park, which are partly a result of constrained resources and partly a result of attitudes towards visitors, are now shared by other parts of Scotland. They are part of a much wider problem in which some of our public authorities now see their primary role as not being about helping people but rather about controlling them. That needs to be resisted and Public Authorities that are taking an alternative approach supported.

Scotland’s access rights, as the Pollok camp shows, provide a crucial means for people to exercise their civil liberties and are more important than ever because of that. But much of the original intention of the Land Reform Act, that government should help people exercise their access rights by creating new paths etc, has petered out since the financial crash in 2008. Footpaths, cycle paths, camping facilities – which have minimum carbon impact compared to building base accommodation – should of course be a key part of our response to the climate and environmental crises. But despite the reams of policy bla bla bla about active travel, the importance of the countryside for physical and health etc, there has been very little action. The COP summit has been a missed opportunity to change that in Glasgow.