On Saturday I walked up the Strone road as part of a round of the Monadliath. It is almost three years since I first blogged about the “improvements” that were being carried out on this road and considered the implications for the planning system (see here). The Cairngorms National Park Authority, to their credit, then decided that because of the extensive nature of the work, it should require full planning permission. Eighteen months later they completed negotiations and granted planning consent subject to a number of conditions. These were finally agreed in December 2019 (see here for planning papers).

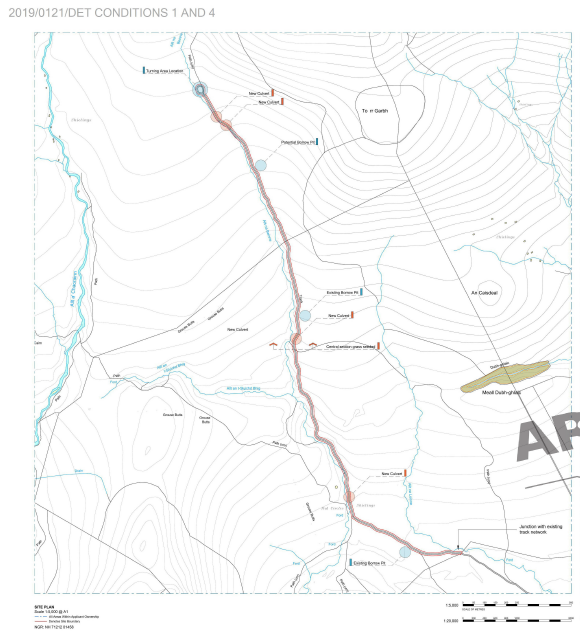

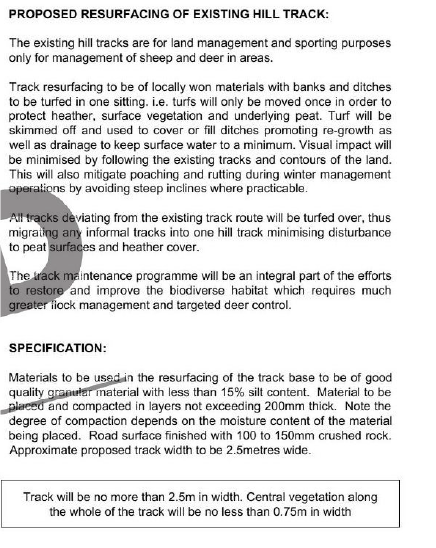

Despite the time taken to agree them, the planning documents are quite brief. The key proposals for how the track might be brought up to the standards one should expect in a National Park are covered in a couple of pages:

This succinct proposal provides quite a contrast to the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority where planning applications are accompanied by reams of paper which often make it very difficult to ascertain what exactly has been agreed.

It is, however, what happens on the ground that counts. At first sight I was not impressed, with the first steep section of track appearing at risk of serious erosion.

It was only higher up that it became clear that this was work still in progress. Unfortunately, although the Scottish Planning Portal allows the start and end dates of work on developments granted planning permission to be recorded, neither of our National Parks use this facility. With planning permission lasting three years, this makes it very difficult for any member of the public concerned about a development in a remote area to monitor what is going on. My visit at this stage in the development was pure chance. A lost opportunity for our National Park Authorities, who talk a good game about making more use of volunteers, to empower outdoor recreationists to help monitor developments in our hills.

From where it steepened, a new surface had been added to the road – as per the planning application – and a new drainage ditch excavated, but neither had been finished.

The basic quality of the work appeared good, .

Further up it became clear that the contractors were working from the top down to complete the surface of the track. The specification, which was for a 2.5m road with a 75mm vegetated strip down the middle, has been strictly observed. While arguably the work might have been better done in the Spring, allowing time for the translocated plants to put down roots, if it survives the winter the landscape impact by this time next year should be very little.

While it is amazing what skilled operators of diggers can do, they do still make mistakes. That is why all work on hill tracks needs to be actively monitored and the workforce advised to change their practice where necessary.

A much bigger issue is that grazing animals, primarily sheep, have trampled over much of the vegetated sides of the road helping to break it up and destroy the vegetation before it has taken root. This damage, which is in no-one’s interests, could be prevented if planning consents for hill roads included a standard condition requiring farm animals to be removed until vegetation has recovered.

In terms of landscape impact, the line of original road was well chosen and is generally hidden from a afar. I identified two concerns about the design. The first is that a couple of sections exceed 14°, the recommended maximum angle for hill roads. While the addition of vegetation to the raised central strip will help reduce the risk of erosion, it is unlikely to prevent it completely. Future maintenance is therefore likely to be an ongoing issue but any alternative route would have had a much greater landscape impact.

The second is the turning circle at the top of the road. There is no need for it. It significantly increases the landscape impact of the road but has also required the destruction of peat to create the new drainage ditch. This should never have been agreed, particularly when the owner of Glen Banchor is being paid public money to restore damaged peatbog elsewhere on the estate (see here).

The implications for the planning system in the National Park

Having taken action to remove the unlawful Glen Clova hill road (see here) and require retrospective planning applications for a number of hill roads on Speyside, land owners and land managers should now be getting the message from the Cairngorms National Park Authority that multi-purpose hill roads need to be approved through the planning system. That is very welcome, even if there is still some way to go.

While I have made a number of criticisms/suggestions in this post, generally the work done on the Strone hill road appears to raise the bar in terms of the standards to be expected in our National Parks and that is also very welcome. In particular, the CNPA appears to be listening to organisations concerned about the landscape. The requirements for a central vegetated strip appear to have been agreed after strong representations on this point from the North East Mountain Trust.

Besides the detailed design issues, it is very important that the road stops where it does and is not extended further into the wild coire lying between A’Chailleach and Carn Sgulain:

Unlike other parts of the Glen Banchor estate, above the end of the road there is little sign of grouse moor or deer management until you approach the summit of Cairn Sgulain:

In my post first on the Strone road I suggested that while all new hill roads should require full planning permission, upgrades could potentially be decided under the Prior Notification system as long as the estate had agreed a specification for such work with the Planning Authority. In such cases they could simply submit the specification and a map showing the extent of the proposed works. Effectively, this is what has happened (eventually) with the Strone hill road. This could potentially incentivise all landowners to develop agreed specifications for road upgrades, based on none being more than 2.5m wide and all have vegetated central strips. On the downside, however, it would also reduce the income Planning Authorities receive, reducing their ability to monitor such work effectively given current financial constraints..

The Strone case does show, however, that good quality hill road upgrades do not necessarily require reams of paper. My suspicion is that it is the commitment of planning staff, the support they get from their managers, their relationship with landowners and contractors, and having the time to monitor development work is what really counts. We need to value professionalism more than bureaucracy.

North East Mountain Trust has, indeed, banged on about the importance of having a central vegetation strip both in respect of new tracks and upgrades outwith forested areas. The reduction in visual intrusion, particularly from a distance, can be very significant indeed: it can be the difference between an ugly scar and a line which merges into the surrounding vegetation. Applause for the CNPA, which is now the leader in Scotland regarding good practice in respect of tracks, for taking this on board. Other authorities please take note!

The timescale for the review of Permitted Development Rights related to hill tracks has now slipped to next spring. Following that, there is an argument that Nature Scot’s guidance on hilltracks should be updated and it is important that this includes the need for a central vegetation strip to be standard practice.