Fires and National Parks

I have been back from Australia two weeks. Yesterday I checked on the fire that had been burning in the Wollemi National Park when I was out there (see here). Its still burning.

I have been back from Australia two weeks. Yesterday I checked on the fire that had been burning in the Wollemi National Park when I was out there (see here). Its still burning.

At the end of October, soon after it started, 3400 hectares of the National Park, the second largest in New South Wales, had been burned. Yesterday the figure stood at 250,700 hectares, an area larger that the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park and over half that of the Cairngorms National Park. Smoke from the Wollemi and another NSW fire was yesterday badly affecting Sydney, just as when I was there, creating serious health risks (see here).

Wollemi National Park was one of the places I had considered visiting, partly because of the famous Wollemi Pine. This was discovered in 1994 in remote canyon and is a species which may have survived since the age of the dinosaurs. While there are only 100 adult trees in the National Park, the tree is not threatened with extinction because within years of discovery it had been propagated in botanical gardens all over the world. Last New Year I even came across a specimen at Inverlael Gardens off Loch Broom!

Unfortunately because of the bush fires access to most of the National Parks on the eastern seaboard of Australia, including Wollemi, was banned while I was in Australia. Droughts, which are becoming increasingly severe with global warming, are making most of Australia’s National Parks drier and as an consequence increasingly at risk from fire.

I managed to visit Strickland forest park – a rainforest remnant – the day before access was banned there because of the fire risk . That was unusual because normally this is in Australian terms a wet place. The stream at the bottom of the valley had reduced to a tiny trickle. This has created major new challenges for the management of protected areas. As they dry out, do you leave them, let dry vegetation accumulate and then risk enormous catastrophic fires? Or do you copy the aboriginal practice of regularly burning off dry vegetation? This reduces the risk of catastrophic fires but promotes species that can recover quickly after fire and which dominate much of inland Australia – that would mean an end to rainforest. There are no easy answer to climate change and we may face similar issues in Scotland if hot dry periods increase: for example, the natural regeneration of large areas of Caledonian pinewood, a species that is helped by fire, could increase the risk of greater areas of native woodland going up in smoke in future while the risk of planted conifer plantations going up in smoke could also increase.

I also managed a kayak trip along the edges of the Hunter River National Park.

However, the next day when I tried to enter the landward part of the National Park with a cousin we were stopped because of the fire risk. We then managed a visit to the botanical gardens for an hour or two before they too were closed because of the fire risk but then I wouldn’t want to have been in one in the case of fire. The environmental armageddon facing Australia and Australian National Parks is quite scary.

However, the next day when I tried to enter the landward part of the National Park with a cousin we were stopped because of the fire risk. We then managed a visit to the botanical gardens for an hour or two before they too were closed because of the fire risk but then I wouldn’t want to have been in one in the case of fire. The environmental armageddon facing Australia and Australian National Parks is quite scary.

Thoughts on the differences between Australian and Scottish National Parks

The observations which follow come from reading and discussion rather than from evidence of what I could see on the ground.

Australia’s first National Park was created outside Sydney in 1879 and renamed the Royal National Park to mark a visit by HRH in the 1950s. It was the second National Park to be designated in the world, following Yellowstone in the USA, and was conceived as a breathing space, somewhere for people living in Sydney which was growing rapidly at the time to escape.

Naturalists, however, soon seized on the idea as a way to save wildlife from the depredations of colonisation. In 1887 when plans were hatched by a Mrs Gordon Baillie to settle a thousand Skye crofters on Wilson’s Promontory in Victoria, conservationists successfully got it designated as a National Park. They then fenced off the area and started to introduce threatened species of animals and plants. They created what the author Tim Low described as a “noble ark”, a sort of animal sanctuary. No consideration, however, was given to how the introduced animals and plants would fare in their new habitats and there were daft introductions including Tree Kangaroos from the tropical jungles of the north into an area where the climate is not that dissimilar to that of England.

Not surprisingly, most of the introduced species on Wilson’s Promontory failed to survive but on Kangaroo Island, the next National Park to be created as a sanctuary, it may surprise people to find that introduced Koalas, platypuses and Cape Barren geese all in time became pests. Exploding Koala populations destroyed the gum trees on which they fed.

It took over half a century before the primary purpose of Australia’s National Parks changed from protecting species – creating arks – to conserving habitats.

Australia now has over 700 National Parks, compared to our two. They range in size from Kakadu, which covers over 20,000 square kms (4.5 times the size of the Cairngorms National Park) to small National Parks in cities such as the 372 Hectare Lane Cove National Park in Sydney – effectively urban nature reserves. Six – including the wonderful Kakadu and Uluru – are run by the national or Commonwealth Government as its called, and the rest by the various states. Each state is slightly different but here I will consider New South Wales.

NSW has 189 National Parks although the percentage of land they cover is slightly less than in Scotland ( NSW is about 10 times the size of Scotland and has 50, 450 sq km of land designated as National Parks compared to 6,393 sq km here).

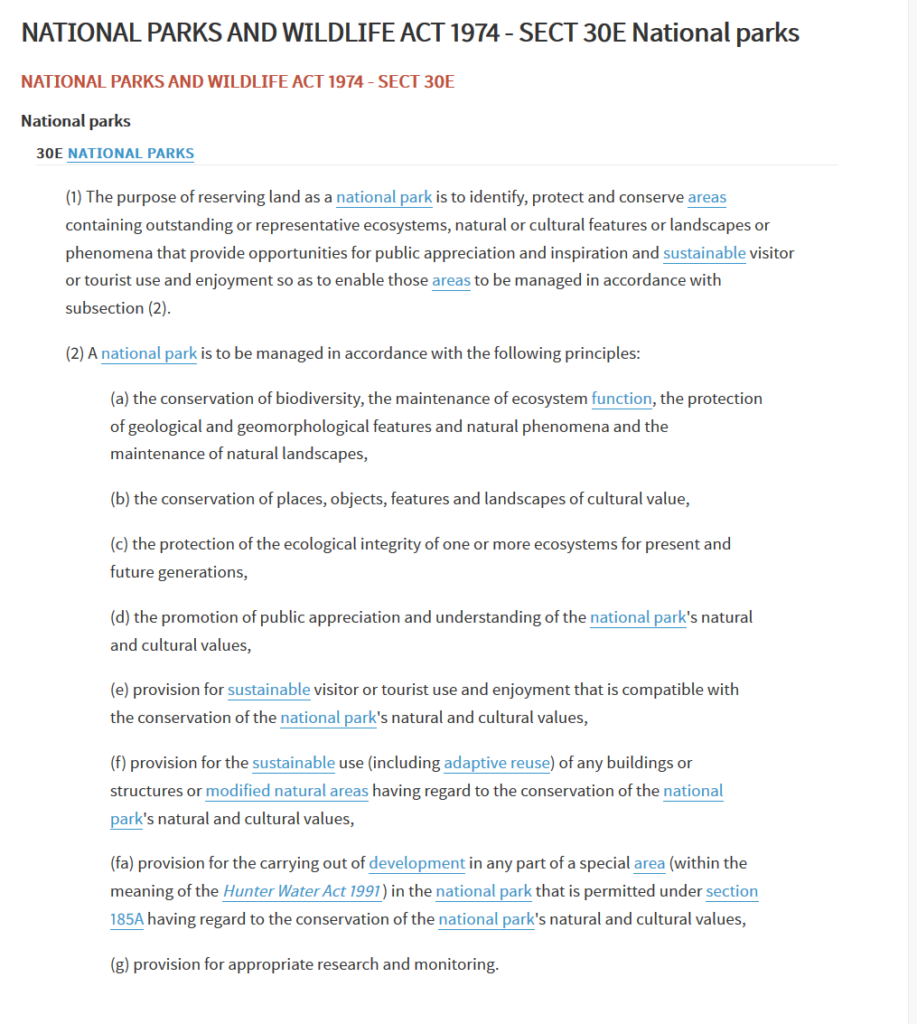

The comparison, however, is not like with like. Australia’s National Parks don’t normally include settlements, with the notable exception of aboriginal settlements. Moreover their aims are restricted to conservation and the public enjoyment of nature:

Australian National Parks don’t have duty to promote and sustainable economic and social development of local communities, as in Scotland, because there are almost none within their boundaries. Nor is there any duty, as in Scotland, to make sustainable use of resources – because in general the National Parks are not exploited for human use. Interestingly, however, the Commonwealth National Park Service announced a $216 million investment – a huge sum of money – for the aboriginal community in Kakadu in 2018/19 (see here).

Australian National Parks are thus reserves which offer a much higher level of protection to nature than our National Parks. They are also managed by a single National Park Service rather than standalone Boards as in the Cairngorms and Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Parks. That doesn’t mean the concept behind our National Parks, which include local communities within their boundaries and local community representatives on their Board is wrong. It does, however, raise the question of whether we should not have more land within our National Parks reserved for nature?

What prevents that happening in Scotland is private ownership. In NSW the state has the power to make new National Parks under the National Parks Act and in the 1990s a large number of new National Parks were designated. Some of these were created on Crown Land and others through compulsory purchase of private land. Apart from the Commonwealth National Parks leased from the aboriginal peoples, almost all Australian National Parks are nationally owned. This makes it relatively easy – there are always dilemmas of course as in the case of fire – to manage them for nature.

My cousins, who are all green, expressed incredulity when they heard our National Parks were mainly in private ownership. Having explained the statutory objectives of our National Parks they asked, “But how did the Scottish Government persuade private landowners to agree to their land being included in the National Parks and that their land should be managed according to these objectives?”. I had to think for a moment before answering “that never happened”.

A penny dropped. Sometimes going to another country and hearing a different narrative about National Parks (or anything else for that matter) provides insights into what is going wrong here. In this case this insight is that:

“The fundamental reason behind the failure of Scotland’s National Parks is that the issue of how land should be managed within them was not addressed right at the start.”

Before our National Parks started to operate all major landowners should have been given the choice either to sign up to manage their land according to their statutory objectives or to sell their land. Instead, the issue of landownership and the right of landowners to manage their land in ways that were contrary to our National Parks objectives was fudged. Our National Parks were set up to fail. The consequence has been fifteen wasted years of attempting to persuade landowners to do the right things voluntarily. We need to fix those issues in our two existing National Parks and before we create any new ones.

Perhaps – as in Australia and New Zealand – a professional Scottish Land Ranger service should be built up. It might help relieve pressure on the misappropriated Scottish Police service resources. (As is well known- Up till almost a decade ago Scotland’s Police were part funded by regional Local authority to reflect local requirements and permit a degree of local autonomy and accountability. The time served concept for a rural service was somehow cast aside in the name of economy and efficiency of command ! The litany of countryside and command ‘mishaps’ since then prove the political intention was entirely ‘wishful’.)

A new National authority, not dissimilar to the Coastguard, under direct oversight of the Holyrood Minister responsible for the environment, reporting to the ‘parliament’, could be used to safeguard rural areas. If this dedicated rural force was trained at least to special constable status, this should appear to be a concept to consider for Scotland .The retained staff could be used for rescue tasks, but then augmented in busy seasons ( as happens “down under”) by students individually recruited to inform and guide the public, during busy holiday periods, and to renovate infrastructure in quieter moments? Another idealistic thought ?

Unfortunately I don’t see any will within the Scottish Government to reform our National Park system. The behaviours all point to our National Parks being used as special areas for encouraging economic growth, (akin to large enterprise zones). In the main our Scottish Government gives lip service to environmental conservation, habitat protection and rewilding – matters to be sacrificed for the sake of economic development.

I appreciate that Australia has the ‘luxury’ of a huge land mass and a much lower population density, so there always will be differences, but your article does stimulate the debate that our National Parks, need a change in the legislative structure to enable them to perform more like National Parks. Also, maybe, there needs to be thought given to having more, but smaller National Parks covering a wider range of natural habitats.