I spotted this sign on my return from walking over Ben Ledi last week (see here). While we walked round the locked gate easily enough and most cyclists could too, it would be a different matter for anyone in a wheelchair or riding a horse who wants to enjoy the extensive network of forest tracks in Strathyre. As a consequence the locked gate constitutes an unlawful obstruction to access rights under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. That needs to be addressed by the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA), as the authority responsible for protecting access rights.

The wording on the sign itself is very concerning:

Ostensibly this message is directed at those who have keys to the lock, a limited number of people who should all know which gates FLS wishes to be kept locked – presumably they will have had to sign for the keys.. If FLS was concerned they might forget to do so a simple sign saying “Please remember to lock the gate” would be all that was needed.

Instead, there is this message which implies that the Strathyre forest would cease to be safe and secure if the gate was left open and the public were able to access the forest by vehicles (which are not covered by access rights) or by wheelchair or on horseback. Just what those threats to safety and security are which require the gate to be locked is not clear:

- motor-racing – perhaps;

- timber theft – unlikely;

- other crime – taking in a vehicle increases the chances of getting caught;

- tree disease – its the forestry industry not the public which is responsible for that;

As the world has become ever less “safe and secure” to most people, government messaging about keeping people “safe and secure” has spread into all areas of public life. It has now apparently been extended to trees and forests – except of course where they are threatened by development as at Flamingo Land (see here)). The “safe and secure” spin is meaningless but the mindset is revealing. FLS’ managers would be far better thinking and planning for how they could enable more people access to the National Forest Estate.

As an aside, this should not only be about enjoying access rights but also making use of all the timber that is currently wasted by FLS through tree harvesting and windthrow:

Added to this waste will be all the timber which will be wasted if Scottish Forestry allows FLS to fell larch trees to waste (i.e not for use) in a vain attempt to stop the spread of the disease phytopthera ramorum through Strathyre (see here).

Back to access rights, half an hour earlier, descending one of the forest tracks in Stank Glen and shortly after passing the community hydro scheme we had stepped over some fallen heras fencing before I realised the monstrous culvert had collapsed and part of the road had been swept away.

It will be interesting to see whether or how quickly FLS repairs this crossing which is clearly their responsibility

It will be interesting to see whether or how quickly FLS repairs this crossing which is clearly their responsibility

With the water level low we crossed the burn easily enough and carried along the track and another path a short way until we reached some more temporary fencing, this time upright, which we stepped around onto another forest road:

The sign and the fencing constitute an order, not a request, and a deliberate obstruction, not just to the core path but to other access routes. There is no attempt to explain the reason FLS has tried to close this path or the location or nature of the damage to the track above. That would allow people, who wanted to walk in that direction up Stank Glen, to make up their own minds and decide where they wished to exercise their access rights.

This section of path/track, which FLS’ management have tried to close to the public, forms part of the core path network around Ben Ledi:

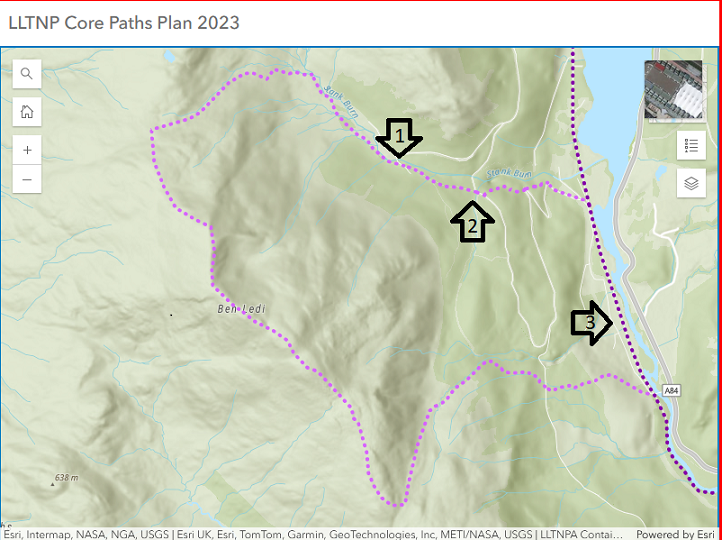

Approaching from the east up Stank Glen (2 on map), the core path leaves the forest track just BEFORE it crosses the Stank Burn (1 on map). The collapsed culvert therefore does not justify the “Diversion” sign below – maybe the flood which appears to have destroyed it also damaged a section of the core path above? But if so, why not just explain the nature of the damage and let people take their own decisions? The fence also, however, forms an obstruction to people whose intention is not to use the track to walk to the top of Stank Glen but to follow it the other way south and is therefore clearly not justifiable on any grounds.

Core paths, the FLS, LLTNPA and Ben Ledi

Core paths were originally intended under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 to provide a network of routes similar to the Rights of Way Network in England which were to be delivered through access authorities developing core paths plans. The LLTNPA has interpreted this to mean (see here):

“Core Paths should be the most important paths (of any width or surface) within the path network which provides the public with reasonable access throughout the National Park.”

Unfortunately, the LLTNPA have failed to plan for “reasonable access” following their initial core path plan (see here) and (here).

Despite the popularity of hillwalking, for example, only hills popular with tourists have core paths up them: the Cobbler, Ben Lomond, Conic Hill, Ben An, Ben Venue. And ONLY Ben Ledi has a circular core path route, with all the other hills having up and down core paths. Now, that one circular path has been blocked by FLS who are trying to divert the public onto other forest roads without any explanation or justification of the reasons they want to do this.

Under the Land Reform Act access authorities have the power to maintain core paths, although there is no duty on anyone in Scotland to do so, but also to make “single amendments” to core path plans (see here). It is not clear whether FLS has consulted the LLTNPA on the “diversion” to the core path up Stank Glen or whether the LLTNPA has agreed to it on either a temporary or permanent basis. Whatever the case the LLTNPA either needs to require FLS to remove the obstruction or, if it believes the core path is too dangerous to use, either get it repaired or start a public consultation about amending the route.

What is happening on Ben Ledi provides another example of how FLS and the LLTNPA are failing to work together for the public good, either in Strathyre or more widely (see here for example). On Ben Ledi the FLS is ignoring the law on access rights and core paths while the LLTNPA is failing to uphold it. After my last post on the disintegrating path up Ben Ledi, I have been informed that it may have been the LLTNPA rather than FLS who agreed with the Nature Lottery to maintain the paths that had been funded through the Mountains and the People programme for ten years. That may or may not turn out to be the case (I have submitted another FOI to FLS asking for this information). While our public authorities squabble about who pays in private the more fundamental issue is that neither FLS or the LLTNPA are serving the public interest and both have ceased trying to promote public enjoyment of the countryside across the National Park.

Every time I read your blogs I do have a chuckle to myself and question whether you live in the real world or a world where everything should go the way you believe it should regardless of the rule or regulation set up to help inform land managers of how they manage the land.

There is a constant theme throughout that you require to know every exact reason to why you can’t got there or why a decision has been made. Has it not occurred to you that the reason that signs are up for diversion is to maybe protect the public from a risk a head? what if something happened if you ignored a diversion sign? who would be to blame? Honestly, from what I gather from reading your blogs you would definitely make out that you are the victim and the land owner was at fault. You go on about access right, but i think you forgot it the “right of responsible access”. Yes you have the right but you must be responsible and if you are advised to not go through a route then you should abide by the warning. If the sign had said no access over a core path then I’d agree they need to offer a diversion rote, but as you picture shows the route is closed but they have offered a diversion to allow you to go on with you walk away from the risk that is ahead. Hence being responsible. This attitude that its my right then to go where I please regardless of what the land owner/land manger says is not being responsible.

Your earlier point regarding harvesting and windfirm edges again is you no having an understanding of forestry practises or the rules that the forestry industry is governed by. This so called “wasted Wood” is not waste but in fact plays a vital role in the biodiversity of the whole forest environment. I would like to point you to read the UK Forest Standard. Within this document we are required to leave at least 20m3 of deadwood per hectare. Deadwood supports up-to one-fifth of woodland species, so the higher the volume of deadwood the high the biodiversity found within the woodland . Again this point does also relate to your issue with the fell to waste that FLS are planning on doing. Again a common practise that allows the felling of trees that is to costly to undertake with conventional harvesters and forwarders. The value of the timber within these trees is within the deadwood they provide rather than the timber that is within the trees.

Your next issue with windblow, this occurs whether you fell to a windfirm edge or not. That forestry and weather for you. There comes a point where you have to stop felling and allow windblow to occur as having a windblown edge can actually be beneficial to the forest as it allows the wind to hit a softer angled edge rather than a solid wall of trees. When wind hits a windblown edge is pushes the wind over the woodland block and reduced the damage that the wind can do. Yes it may look “ugly” but it serves a purpose. If you kept felling trees that were blown, you would run out of forests very quickly. Trees blow down.

I also must make comment on you wording of “small local saw mills could use timber like this if they had not been driven out of existence by industrial forestry”, whether you understand or not, in Scotland we still have small sawmills that are doing very well alongside the larger sawmills. These sawmills will pay the same prices for timber as the larger sawmills. Also whether you like it or not forestry is an industry, these forest have a main purpose of producing timber on an industrial scale, that is their purpose, similar to a farmers field planted with oats or wheat. The UK is the second largest net importer of forest products in the world, this figure is honestly shocking. We should be producing as much of our own timber as possible, and these areas of FLS ground or private forestry need to provide this timber.

I would love to see how you’d manage a mixed estate or a commercial forestry plantation and then see how people criticise your efforts.

Surely public agencies should be complying with access legislation, particularly in a National Park?

From reading the post they have not stopped any access to the woodland. Yes there may be issues with the road being swept away, but if you look at the map there is other routes. As i have already mentioned there is a diversion in place.

Repairing a washed out road is not a straightforward process, there is many hoops to jump through to get permission to fix a road especially in a national park and especially going over a watercourse. Its not a simple task of putting in an excavator and fill in the gap with a new pipe.

The locked gate may restrict all access to the forest, but again if you read the access code it states “Where appropriate, work with your local authority to identify routes, including core paths that can be easily used by people with a disability. Wherever reasonably practicable, provide gates, rather than stiles, on paths and tracks. This will help some disabled people, such as wheelchair users.” It does not state that every path and every forest must be accessible for all users but only where it is practical. If FLS have decided that this gate must be locked al all time then there is a reason whether that be illegal users in the woodland, fly tipping etc.

The locked gate may well be sensible. We have a major problem with illegal 4×4 drivers entering my local forest which in winter does series damage to the ski trails and all year round damages a number of trails that are not designed for vehicular access. Even with locked gates we have had problems with them driving off road around the gates, such that obstacles have had to be put in place ( by FLS) to prevent it

Hi James. This is state forest land, owned by us. Not a private concern. We fund FLS to manage forests sustainably and to provide access and other non market benefits. Your comment about wind blow is typically contrived …in reality we have pushed shallow rooted species on to sites with high risk of windblow simply because they grew faster. Foresters should have known better but the accountants made the decisions. Your comment about small local saw mills doing very nicely is yet another convenient lie. Over the last 30 years around 70% of small Scottish sawmills have gone out of business. There are now virtually no forestry jobs in remoter areas in Scotland. All the benefits from timber go straight into the international accounts of very powerful and rich corporations. All the local community gets are huge industrial clear fells, soil erosion, and countless timber vehicles on unsuitable single track roads. Yes James we have a lot to be thankful for.

There are various aspects here which suggest the existance of a mindset that access is associated with paths and tracks, there is no such restriction in the access legislation so damage to a path or track is no reason to restrict access which could legally be taken even if the path, culverts etc. did not exist, as with earlier articles pointing out “keep to the path” signs on various pretexts which have no basis in law.

I have encountered several instances of paths and tracks blocked supposedly for forestry operations which haivng ignored them turn out to be non existant or long ceased, certainly not active at the time.

The comment above that access for vehicles may be restricted to prevent “environmental damage” misses the point of the article that such has no connection to “safety and security” which is typical modern alarmist rhetoric. Apart from which, logging tracks are built for use by heavy machinery and trucks, 4x4s are not going to damage them.

How about an article on the ever increasing spread of 3M high impenetrable “rewilding” fences preventing access to more and more of the countryside?

Reading these comments – from someone who is apparently a forester – about restricting public access to forest paths being the justifiable “right” of land managers, is hard to take.

Then going on to say that forest operations give FLS and others who harvest trees some valid excuse to close whole regions while creating a devastated mess in “private” . To also claim that once the clear-fell of commercially viable timber has been extracted, debris can be left in place, because industrial ‘mess’ must be good for the environment, is a nonsense.

Forest operations, where growth takes decades – if not permitted to continue for centuries – is not like seasonal crop growing on an annual basis. To try to claim this for forestry is nothing less than an equally self-serving excuse for hap-hazard bad practice. ( tilled fields by contrast will be replanted within months and recover.)

It may be hard for the foresters to come across a highly factual blog which assesses the law and then highlights bad practice in relation to public access.

Attacking the message because criticism is inconvenient does not prevent fact from being brought into the open by Nick’s well argued blog. Evidence of bad practice on Scotland’s hillsides he draws attention to, does not go away by itself.

Open access legislation is being undermined thanks to a severe and orchestrated challenge from centralised organisations ( eg: FLS, National parks, and local authorities) , the very bodies once intended to safeguard that hard won public right for Scotlands public. Spurious public safety excuses are being rolled out by commercial interests and central authorities as excuse for trashing the environment, instead of seeking public cooperation should actual risks exist.

We all have an natural ability to sense risk. In the open access legislation, it was not left to be within the remit of commercial operators to seek to flout the public right, or, in absence of effective oversight, undermine the law.