On Tuesday I went with friends who were staying for a walk over Ben Ledi, a chance to consider further how Forest and Land Scotland (FLS) are managing the land they own in Strathyre (see here) from a recreational perspective. Ben Ledi is one of the most accessible and popular hills and people were already descending the path as we were setting out at 10.30am.

Unless upland paths are well designed/constructed and regularly maintained they can deteriorate very quickly through the impact of water and feet. This poses major challenges in Scotland, in part due to our wet climate but also because there are generally far fewer footpaths up most hills than south of the border and this serves to concentrate visitors, increasing the rate of wear and tear further.

The most recent pathwork on Ben Ledi, which I blogged about in 2021 (see here), took place 2016-18 as part of the Mountains and the People (TMTP) Project.

While the path was already seriously eroding in 2021, that process has continued. A couple of plastic culverts which were half exposed in 2021 are now totally exposed (see above) while more are emerging as the path surface has been washed away:

As the surface of the path below stone steps, the erosion becomes worse as people try and get round what becomes a barrier rather than an aid to progress (research has shown the average person avoids steps which are more than c8 inches high):

What happens is that as the surface of the path below and between steps is eroded, steps which were in some cases quite low become higher and people start to go round them.

The new routes round the steps then become drainage channels which speeds up the rate of erosion further:

While there are some sections of the path up Ben Ledi which are still in a good state, significant sections have failed in less than 8 years. According to the Mountain for People Project about £500k was spent on the Ben Ledi path. Much of that money has been totally wasted.

While boulders have been placed on either side of what was intended as a stone staircase to keep people on the path, people have avoided the too-high steps where-ever they can. In my view this is a fundamental design flaw. While more boulders at the side of the lower section of the path in this photo could have forced people to keep to it, the more fundamental problem is the path is too steep: it should, as in the Alps or on the fine old stalkers tracks, have been designed to take a more zig zag course.

There are similar design failures on some of the flatter sections of path. Much of the fine material on this section had already washed away in 2021 (see below) leaving an uneven surface that was difficult and uncomfortable to walk on. As a result people soon started to walk along the ground between the edge of the path and what was a drainage ditch.

A comparison between the photos shows that in the last three years more fine material has been eroded from the surface of the path, making it even rougher and difficult to walk on, that the desire line (yellow) has spread but is now itself eroding (there are signs of bare earth in top photo) and interestingly that the line of vegetation along the former edge of the path, which is too steep to walk along, has developed significantly into a thicker and more continuous green line.

The top section of the path onto the summit of Ben Ledi, which I understand was not included in the Mountains for People Project is in an even worse state and illustrates just how little senior management at FLS, whose primary care is timber sales, care about facilitating outdoor recreation and protecting the landscape:

This upper section of the path had, like the lower section of path, been subject to repairs/construction work before the Mountains and the People Project and, in 2021, at the time of my last visit the remains of stone steps were still visible on this section. Without ongoing maintenance, much of the path work undertaken by the Mountains for People Project could end up looking like this.

While some of the erosion problems illustrated above would require the path to be redesigned, others could have been prevented or addressed if the path had been maintained properly.

Some of these maintenance tasks are very simple. Ensuring cross drains, which are designed to drain water off the path, or side drains are kept free of material is a simple job which would enable them to continue to fulfil there intended function but FLS does not appear to have even done that.

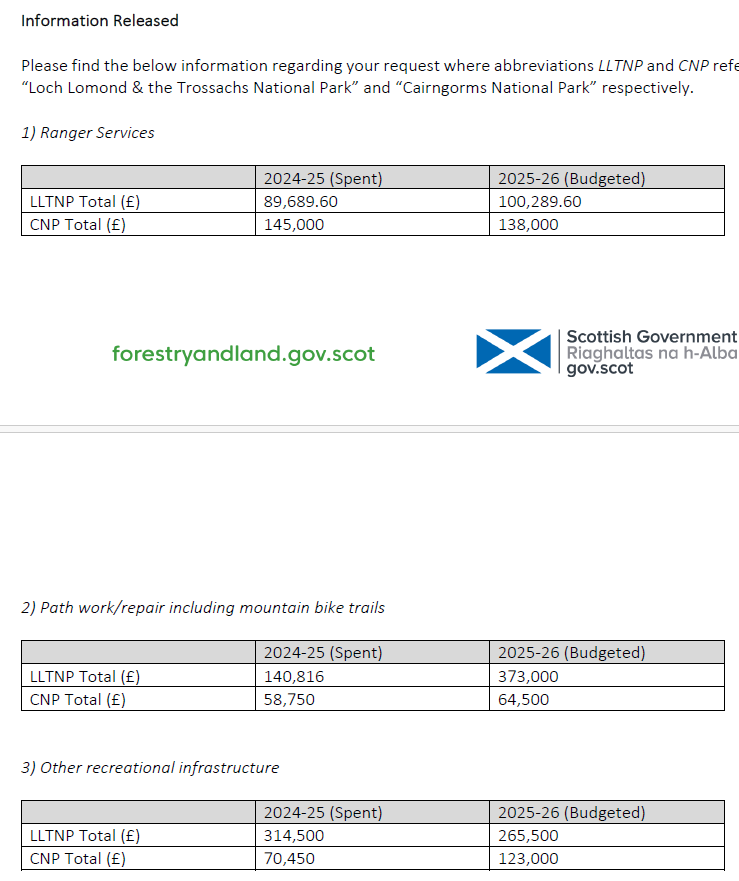

After visiting Strathyre to look at how FLS’ Larch Removal Plan would affect red squirrels and raptors I submitted a Freedom of Information Request to ascertain how much FLS had spent in our two National Parks on outdoor recreation and conservation, including footpaths, in the last two years:

Unfortunately, I failed to ask FLS what income they raised in National Parks through recreational charges (I will now ask) but my estimate is that after taking income from car parks, leasing of land for campsites etc they are now investing nothing in outdoor recreation. That would fit with their decision to stop managing the Sallochy campsite and the abandonment of other recreational infrastructure. Whatever FLS’ investment, however, clearly they are not spending enough on paths. This is storing up even bigger problems for the future, as popular paths are allowed to fall into ever greater states of disrepair, but also undermines the statutory objectives of our National Park to promote public enjoyment of the countryside.

While our National Parks exhort people to “keep to the path where possible”, they have said nothing about how the path network is deteriorating or, as importantly, how much investment is required. Mairi Gougeon, the Cabinet Secretary in the Scottish Government responsible for both FLS and our National Parks, is currently responsible for these failures but they go back till before the TMTP Project.

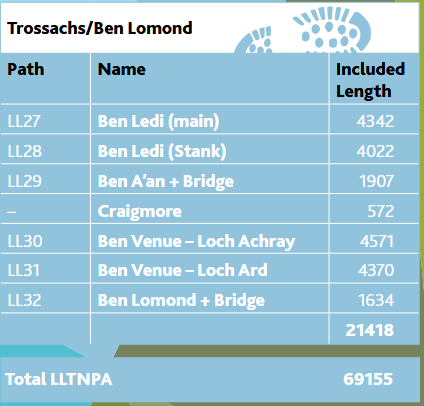

In fact the TMTP project was supported by both FLS and our National Park Authorities as a way for them both avoiding to have to pay for path work. The majority of the paths repaired in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park were on FLS land:

The final Mountains and the People (TMTP) Report (see here) shows the amount that FLS contributed to the “the project funding package of £5.6m” was paltry compared to what was invested by the lottery

- NLHF (Lottery) 58%;

- OATS (Outdoor Access Trust Scotland) 14.9% (including 8.6% raised and underwritten within project by OATS from Charitable Trusts & Donations/Corporates )

- LLTNPA 9.3%;

- FLS 9.3%,

- CNPA (Cairngorms National Park Authority) 4.9%;

- NS (Nature Scot) 3.6%.

FLS paid out less than £560k, when the cost of the path work on Ben Ledi alone was almost that.

However, according to the Final Report of TMTP “10 year maintenance obligations” were agreed with the Natural Lottery. It is not clear the extent to which those obligations were assumed by FLS (another FOI will be submitted) but it is now time for a complaint to the National Lottery because the evidence shows that much of the money they invested in trying to improve paths on FLS land has been completely wasted and that neither the LLTNPA nor FLS have been fulfilling their obligations. What should have happened of course is that following the project both organisations should have created path maintenance teams, instead of outsourcing path work and in that way created an enduring legacy which would have benefitted visitors.