Since my post on how muirburn is responsible for a significant number of wildfires (see here) I have been contacted by a number of readers who have provided further information and photographs including what happened on the Tinto Hills SSSI (formerly a Site of Special Scientific Interest but now, in one reader’s words, “a site of severe scorching and incineration”).

Somewhat ironically the name Tinto probably derives from the Gaelic ‘Teinnteach’, meaning fiery. This is thought to be a reference to its use as beacon hill.

“During the spell of good weather at the start of April the Upper Clyde Valley was shrouded in smoke for about ten days emanating from fires on the Southern Uplands and particularly from Tinto Hill. Tinto Hill (707m) is the iconic South Lanarkshire landmark which attracts large number of hill walkers and is part of the Tinto Hills SSSI. The almost constant burning continued until the 12th April when the weather finally broke.”

While Environmental Health departments of local authorities have the power to address any air pollution caused by villagers burning garden waste, they have no legal powers to prevent landowners setting fire to hillsides whatever the smoke risk. On the evening of 10th April, Symington, a village of around 750 people, was totally engulfed by smoke as what had almost certainly started as muirburn turned into a wildfire. (I say “almost certainly” as proving exactly who was responsible in a court of law is likely to be as difficult as proving who is responsible for killing raptors).

Environmental health law clearly needs to change but the Scottish Government also needs to make legal aid available to anyone forced to inhale smoke so they can sue the landowners responsible for damage to health – which requires a less standard of proof.

Half an hour later on 10th April the muirburn was clearly totally out of control. The “wildfire” went on all night and continued until dusk on 11th April destroying the vegetation on a large part of the hillside.

Both the current Muirburn Code and the revised version out for consultation by NatureScot (see here) state that “You must not…………burn between one hour after sunset and one hour before sunrise”. Carrying out muirburn during periods of very high fire risk is irresponsible enough without continuing to do so as it gets dark. Whether that was an additional factor which helped cause the muirburn get out of control in this case deserves investigation but there is absolutely no justification for allowing people to burn in poor light. At the very least the Muirburn Code should be revised to say “ALL muirburn should be extinguished by an hour BEFORE sunset and no muirburn should be started until an hour AFTER sunrise.

The fact that much of the muirburn carried out on the Tinto Hills SSSI did not get out of control should not be used to disguise the fact that carrying out muirburn during times of high fire risk is a wildfire waiting to happen – however well planned and however experienced those involved.

Two crucial facts that proponents of muirburn as a means of reducing wildfire risk fail to mention is that it can and will, if carried out in the wrong conditions, jump firebreaks and that it does not in itself create firebreaks. That explains why a significant proportion of the revised muirburn code sets out what firefighting equipment those responsible need to have on the hill and why the Cairngorms National Park Authority is now funding the very rich owners of grouse moors to buy firefighting equipment.

In the photo above (A) shows a patch of hillside, surrounded by a mown strip designed as a fire break to contain muirburn, which the wildfire jumped across and incinerated. (B) by contrast shows a recent patch of muirburn which was successfully contained within the mown strips, as with the previous (now green) patches on either side of it. The point here is its the mown strips, not the muirburn patches, which form the firebreaks and, while they help contain muirburn carried out in low risk conditions, they are of limited use in very dry conditions.

To the right of (A) and (B) is a track along the summit ridge. This clearly helped contain the northern boundary of the fire, in part perhaps because the muirburn was started by the track and the wind was blowing from the north but also because being free of any vegetation the track formed a better fire break than the mown vegetation. Once out of control, however, muirburn and other types of wildfire can quite easily jump tracks.

(C) marks a much larger area patch of muirburn. Its hard to tell from the photo whether there were other large patches like this within the wildfire area but its obvious dryness suggests it would have burned rather than formed a firebreak if the wind had been blowing in the opposite direction.

To the south of the summit of Tinto there is another area where muirburn appears to have got out of control and jumped various breaks and changes in the vegetation before being contained by boundary walls and greener (moister) areas less vulnerable to fire. The best way to reduce the extent of wildfires is not to burn the landscape, which promotes vegetation tolerant to fire like heather, but to rewet it by enabling other vegetation to develop and create fire breaks in areas of greatest risk.

Burnt hillsides dry out more quickly, both because the protection afforded by vegetation to the effects of sun and wind are greatly reduced but also because any rainfall runs off more quickly.

NatureScot, the Muirburn Code and the mis-management of the Tinto Hills SSSI

There are two main landholdings which cover the Tinto Hills and its SSSI, the St John’s Kirk Estate and, to the west, the Eastend Estate owned by J and A Galloway Ltd. A much smaller area just to the south of the summit is owned by West Millrig. From the photos and from memory there is little or no muirburn on the Eastend Estate and most of the muirburn as well as the recent wildfire took place on the St John’s Kirk Estate.

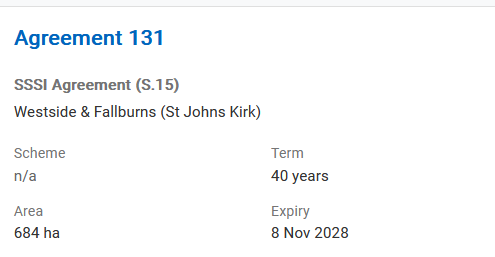

NatureScot’s sitelink site contains information about the SSSI and its management (see here)much of which is now old and out of date. The Tinto Hills were designated a SSSI because of its famous sorted stone stripes, its upland assemblage and subalpine dry heath. Back in the 1980s the Nature Conservancy Council Scotland entered into a legal agreement with the two main landowners for the management of the SSSI. That for St John’s is due to expire in three and a half years time:

Unfortunately, almost 40 years on, NatureScot still does not publish its SSSI agreements or provide any information about what it might have paid to landowners as a consequence. That culture of secrecy is not in the public interest or the interests of Scotland’s most important sites for nature.

According to the most recent Site Management Statement, which was last updated in 2008:

“The SSSI forms part of several farms, the main area being within St John’s Kirk Estate, which is currently used for upland grazing………………Muirburn, swiping and bracken control are undertaken within parts of the site. Most of the SSSI is under several management agreements some of which support positive management within the site”

Rather than questioning muirburn whether muirburn was the best way to manage this site, NatureScot incorporated it into the first objective of the 2008 Site Management statement:

“To maintain the condition and increase, where possible, the extent of the upland habitat and associated communities by ensuring grazing is carried out at appropriate levels and muirburn is carried out following the muirburn code of good practice.

Appropriate grazing regimes will require sufficient grazing to prevent dominance by more competitive grass species, but not so much grazing that the typical flowering plant species are unable to flower and set seed in reasonable abundance. The vegetation should continue to support key species such as stiff sedge and mountain crowberry. Grazing should be targeted where and when it will be most beneficial to the dry shrub heath. Grazing animals are attracted to the regrowth of young vegetation on recently burnt ground or swiped areas.

Numerous, well-dispersed fires and swiping of significant areas away from footpaths and sheep tracks can help to spread out and dilute the impact of grazing.”

It appears from this that NatureScot’s primary justification for continuing muirburn on the Tinto Hills site was to concentrate sheep grazing on the burned patches and so save the plants which it wanted to protect from being eaten by sheep. That suggests there was no conservation justification for the muirburn. It is unclear from the information on sitelink whether the undertaking in the management statement “to monitor and research” the consequences of this approach ever happened. The question which now needs to be answered is which plant communities on the Tinto Hills site were in the better state before the recent wildfire, those on the unburned Eastend estate or those on burnt St John’s Kirk, and the explanation for this.

Whatever the answer, the recent wildfire is likely to have destroyed many of the plants which the SSSI was designed to protect – if they had not previously been destroyed by muirburn!. Intentionally or recklessly damaging the natural features of a SSSI is a criminal offence and it will be interesting to see if a criminal prosecution is now brought in this case.

The Site Management Statement does not contain any indication of areas within the SSSI where muirburn should not occur and only requires the landowner to abide by the Muirburn Code which gives the landowner considerable discretion. Since burning on SSSIs is legally an “operation requiring consent” NatureScot could have exercised far more control over the use of fire than they have. They and had every justification for doing so because subalpine heath has been in unfavourable condition for many years, in part because of burning:

“The vegetation structure due to disturbance from burning has also contributed to the feature’s unfavourable condition. Large fires in 1996 occurred over sensitive areas; the steep slopes at Maurice’s Cleuch and adjacent to Cleuch Burn”

As for the muirburn code, that has been revised since 2008 and the current version dating from 2017 states:

“Summits, ridges and other areas very exposed to the wind…………. should not be burnt, as vegetation is kept short by high winds (wind-clipped); burning has no benefit and risks removing vegetation cover, leading to erosion”.

Judging from the aerial photos, St John’s Kirk Estate has been ignoring that advice and burning areas exposed to the wind – where plants like stiff sedge for which the site was designated are found. It also appears to have been burning the lower areas far more intensively than advised in the Muirburn Code.

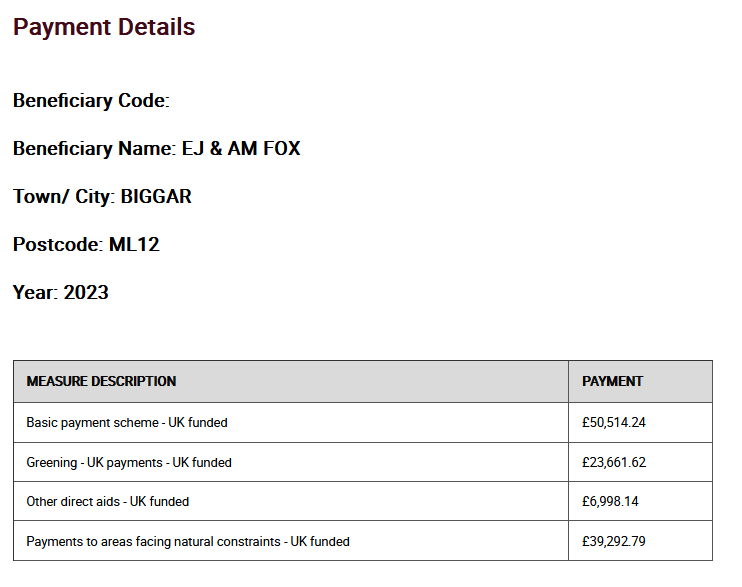

Besides any money that has been paid to them by NatureScot under the SSSI Agreement, the owners of the estate have received rural payments from the Scottish Government. In 2023, the last year for which figures are available, this amounted to £120,466.79, a significant sum of money:

Failure to abide by the Muirburn Code can in theory result in certain rural payments being suspended or withdrawn. It would be interesting to know whether NatureScot has ever tried to use this to influence the management of the Tinto Hills SSSI but following this wildfire there appears no justification for the Scottish Government to continue to fork out scare public money to the landowners.

This post has shown that instead of addressing the alleged need for muirburn on the St John’s Kirk estate or the way it has been practised, NatureScot has allowed dangerous and damaging practises to continue unchecked. It has thus failed in its statutory duty to protect the natural world. Unfortunately, rather than learning from these failures to protect the natural environment, NatureScot is now proposing to weaken the Muirburn Code still further as explained in recent posts (see here for example).

NatureScot is totally unaccountable to the public so it is going to take political pressure for them to change their position. Please consider therefore contacting your MSP/MSPs alerting them to what is going on and asking them to intervene so that the proposed muirburn licensing scheme offers better protection to both people and nature.

1 Comment on “Muirburn and wildfires – the case of the Tinto Hills SSSI (Site of Severe Scorching and Incineration)”