On 19th March the Herald revealed (see here) that Scottish Forestry, having suspended grant payments to BrewDog after it was revealed many of the trees in the Lost Forest had died, has now paid them £1.2m and agreed to pay a further £1.5m for the project. This post takes another look at the scandal in the light of what has been happening over the last year.

What is the £1.2m paid out by Scottish Forestry to date for?

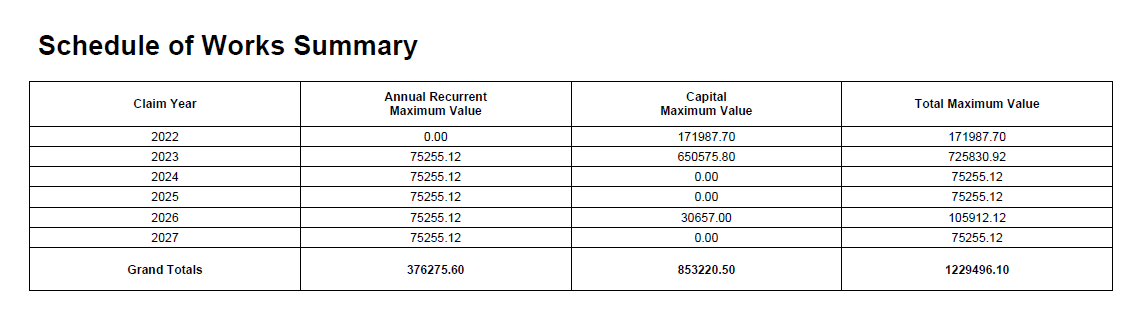

BrewDog’s Lost Forest is split into two different phases covering two different areas. Phase one, where the trees died, is on the Strathspey part of the estate and lies within the Cairngorms National Park. Scottish Forestry’s contract with BrewDog for Phase 1, obtained through an FOI request, shows they had committed to paying a total of £1,229,496 to be paid over six years and that the most that should have been paid by now is £970,372:

A year ago another FOI request (see here) established that Scottish Forestry had by then paid £690,986.90 to BrewDog for Phase 1. That is c£280k less than should have been due by now if all had gone well. Whether Scottish Forestry is still withholding any of this outstanding amount of public money until BrewDog has replaced all the dead trees is unclear (a Freedom of Information request is in the pipeline).

What is clear is that if the £1.2m payment to date reported in the Herald is correct, Scottish Forestry must have also paid BrewDog for some of the capital costs for Phase 2 of the Lost Forest, which is over the watershed in the catchment of the River Dulnain.

Why did so many of the planted trees die?

Scottish Forestry has allowed BrewDog to proceed with their Phase 2 planting without any inquiry into why so many trees died in Phase 1. The reason is Scottish Forestry are only interested in meeting the Scottish Government’s planting targets not whether the trees survive or not. In an extraordinary statement Scottish Forestry have now stated to the Herald that:

“the loss of a proportion of trees post planting is very common, nothing that unusual has occurred at the Lost Forest”.

That contradicts the “very high mortality” and “high mortality” of some species reported by Scottish Forestry’s own staff in the limited inspection they had undertaken on 7th September 2023 (see here). It also contradicts what their own spokesperson was reported as saying in the Daily Record a year ago after the scandal emerged in the press (see here):

“The level of loss here is higher than normal which may be down to climatic factors after planting”

Indeed last April James Watt, then CEO of BrewDog, stated (see here) that:

“Our partners have estimated that around 50% of the 500,000 saplings planted did not survive their first 12 months”.

If there is “nothing unusual” about 50% of trees dying, there are two serious implications for the Forestry Grants system. The first is that the failure of the Lost Forest planting was not just down to “last summer’s extreme conditions resulted in a higher-than-expected failure rate, particularly Scots Pine”, as James Watt claimed last year, but to something more.

The second is that the Scottish Government may be meeting far less than its intended woodland expansion targets through planting, not just because the number of trees are falling below targets but because so many die. (Another FOI is in the pipeline to Scottish Forestry about the data on which their “nothing unusual” claim is based).

While the drought in the Spring of 2023, soon after most of Phase I of the Lost Forest was planted, was the precipitating factor which resulted in so many trees dying, it was not the main cause. In my view it was the “mounding”, carried out under the aegis of Scottish Woodlands, which exposed peaty soils to the sun causing them to dry out and the removal of the surrounding vegetation which holds in moisture that was responsible for the drought having such an impact. These consequences of mounding, as the photo above shows,are not short-term but ongoing. They means that any trees that are replanted are at high risk of dying in future hot dry periods.

The problem is made worse by the impact of large tracked vehicles which destroy more vegetation and expose more peat to the sun (causing it to oxidise and release soil CO2 into the atmosphere). This explains why the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA)’s draft Integrated Wildfire Management Plan (see here) identifies new woodland plantations as a source of very high fire risk. Unfortunately that plan presents another missed opportunity to address the source of the problem by stopping the planting of new plantations of native trees.

The contrast between the natural regeneration and planted areas within the Phase I area of BrewDog’s Lost Forest is striking. While vegetation cover like heather may slow down the establishment of trees, it does not prevent it and once established those trees are far less vulnerable to drought.

As I have previously argued there was no need to plant trees in this area, natural regeneration would have done the job far better if deer numbers had been kept below 2 per square kilometre (see here) . Scottish Forestry, however, instead of requiring BrewDog to employ local stalkers have handed BrewDog £1.2m to date with a further £1.5m committed – their only justification for doing this is to try and meet the Scottish Government’s tree planting targets.

Despite all the money that Scottish Forestry has paid BrewDog to erect killer deer fences (see here) in January there was clear evidence of continued deer browsing within the enclosure and one of my local contacts has reported seeing a stalker at work there subsequently.

There is also browsing by mountain hares. Removing much of their food supply by clearing patches of vegetation to plant trees and mountain hares are even more likely to eat the trees!

Scottish Forestry’s grant system, which supports planting lots of trees all at once because its cheaper financially makes the problem even worse. It creates an easily accessible new food source causing hare numbers to boom while in turn results in even more planted trees dying.

Once mountain hares were legally protected year round in March 2021 that should have prompted a review of the whole model for planting native trees in upland areas. Instead Scottish Forestry and the forestry industry carries on regardless. (I have submitted an FOI to NatureScot for the number of licenses that have been issued to forestry interests to cull hares in the Cairngorms National Park since they were protected).

Other important factors that are responsible for the high failure rate of BrewDog’s tree planting include the pressure on contractors to plant as many trees as quickly as possible – which results in some trees not being planted properly – and the lack of suitable mineral soils where trees grow best on the upland parts of Kinrara .

BrewDog’s replanting

The main reason why Scottish Forestry doesn’t care whether trees survive or not is they don’t treat it as their problem and have no long-term interest in whether the new “woodland” is successful or not. Ostensibly Scottish Forestry protect themselves in the short-term against the risks of the publicly funded trees dying by requiring grant recipients to meet various target densities of live trees five years after planting. That means that BrewDog risks Scottish Forestry trying to reclaim some of the £1,229,000 it awarded for Phase 1 of the Lost Forest if it doesn’t try and replace the dead trees.

What happens after five years, however, is no concern to Scottish Forestry. The result is all the factors which caused BrewDog’s initial planting in Phase I of the Lost Forest to fail (planting in inappropriate areas, the use of damaging techniques etc etc) will continue and much of the new plantation is unlikely to develop into native woodland.

A year ago James Watt claimed “we have already replaced 50,000 of the baby trees that did not survive the winter”. With the Herald now quoting BrewDog as stating “80% of lost saplings had been replaced” and the “remaining 20% is planned for the next available planting season”, that means c50,000 trees still need to be replanted.

When I walked across part of the Phase I area of the Lost Forest in January there was both evidence of replanting activity but also of plenty of places where this had not happened.

In the snow it was not possible to ascertain how many of the leafless deciduous trees which remained were alive or to ascertain how many of the dead or missing trees had been replaced. My guesstimate, however, was it was significantly less than 80% which means if the claims reported in the Herald are true, there must have been significant replanting activity in the last three months.

The cost of the replanting and what is BrewDog really investing in Kinrara?

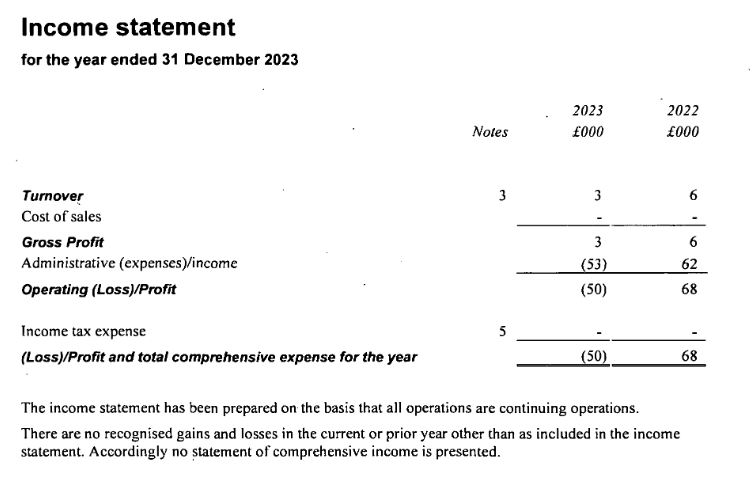

BrewDog’s last accounts (unaudited) for the Lost Forest Ltd, the company through which it owns the Kinrara estate, were filed on 9th December 2024 (see here). They show that, as in the previous financial year (see here), the Lost Forest Ltd has not generated any income:

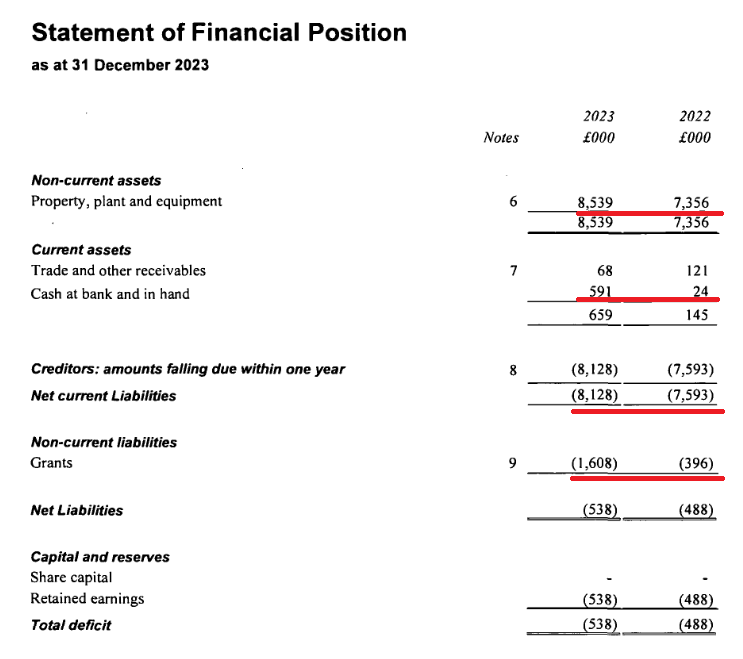

The balance sheet for the company, however, does show some significant income/cash movements:

The statement of financial position shows an almost £1.2m increase in value of property, plant and equipment. This is attributed in Note 6 to “additions”. How the money stacks up is not explained but there is nothing in the financial statement to say that the land at Kinrara has been revalued so it appears in some way to reflect things funded by the public or paid for by a transfer from BrewDog (which does not have to be reported because of exemptions under company law). The sum, however, does not appear to include the capital items funded by Scottish Forestry for Phase 1 of the Lost Forest as the only grants recorded under Note 9 are for Peatland Restoration.

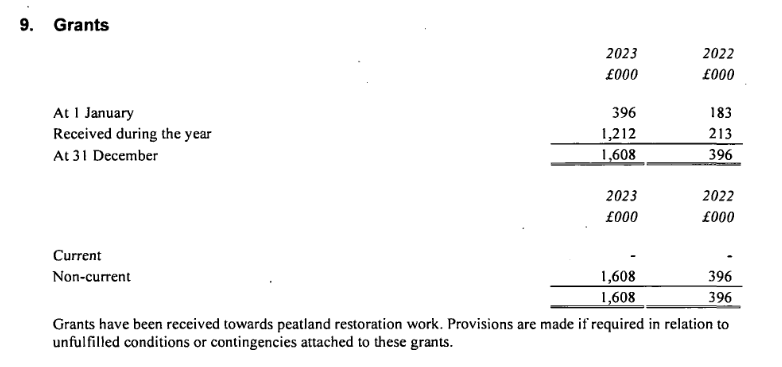

The reason why these grants for peatland restoration are shown in the financial statements as a liability is that they, like the forestry grants, could potentially have to be repaid if the restoration work was judged by NatureScot to have failed.

Despite the lack of any reported income, cash in hand for the Lost Forest increased by £567k in the year. Again, this is not explained but it could peatland restoration grants that were received by the Lost Forest Ltd and not spent. It raises the question of whether BrewDog PLC has been paying directly for some of the works at Kinrara instead of doing this through its subsidiary which received the grants? That would help explain why Note 8 explains the amount the Lost Forest owed to its parent company increased by £510k last year.

Note 8 also shows that £8,078k of the £8,128 owed by the Lost Forest is to BrewDog PLC. It is possible that the remaining £50k is owed to HSBC who registered two charges over the property in June and August 2023. While I stated last year that the amount and purpose of these charges were unknown (see here), I missed the fact that the second charge was to guarantee a loan facility BrewDog had negotiated with HSBC. If the unaudited financial statements are correct it appears that this loan facility was not used in the year to December 2023 and the maximum amount loaned under the first charge was £50k. That is surprising as why would a large company like BrewDog go to the effort of taking out a loan for a piddling £50k? But it also provides further evidence that BrewDog, despite its claims (see here), had invested little or anything in the Lost Fores, whether directly or indirectly by taking out loans, up until the end of 2023 .

Given BrewDog is likely to have subsequently had to pay the costs of replanting all the dead trees – unless it somehow manages to force Scottish Woodlands or their contractors to assume liability for this – far more activity should be reported in the financial statements for the Lost Forest due next December. From a public interest perspective, however, the lack of transparency I have highlighted to date could be addressed if Scottish Forestry required all grant recipients to provide fully audited accounts which accurately reflect how public monies have been spent and how much pf their own money the landowner has invested.

The Lost Forest and value for money

While Scottish Forestry is completely uninterested in whether the largesse it distributes to the forestry industry represents value for money, last month BrewDog founder, James Watt, announced (see here) he was launching an unofficial “underground cousin” to the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) that has been set up under Elon Musk’s in the USA. If the promised hotline for whistleblowers to highlight waste ever emerges, it deserves to be inundated by people expressing concerns about the Lost Forest and all the other wasteful expenditure by Scottish Forestry.

While Scottish Forestry is completely uninterested in whether the largesse it distributes to the forestry industry represents value for money, last month BrewDog founder, James Watt, announced (see here) he was launching an unofficial “underground cousin” to the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) that has been set up under Elon Musk’s in the USA. If the promised hotline for whistleblowers to highlight waste ever emerges, it deserves to be inundated by people expressing concerns about the Lost Forest and all the other wasteful expenditure by Scottish Forestry.

Apparently James Watt aims also to assess UK Government spending using Freedom of Information (FOI) requests. The question now is whether Mr Watt will submit Freedom of Information requests to Scottish Forestry to establish whether all the grants they are handing to self-professed green landowners and the forestry industry to plant commercial sitka and native woodland plantations represented value for money? These FOI requests could be extended to Transport Scotland with evidence from England (see here) showing that roadside planting schemes have, like the Lost Forest, had very high failure rates and been a disastrous waste of public money. Those campaigning for reform of Scottish Forestry and the industry it supports would accept the help and might even welcome it if Mr Watt was to admit the Lost Forest has been a serious mistake.

Skewed reporting, cherry picking sensational elements that do not support a real world situation. Rewilding is absolutely irrational throughout most of Scottish Highlands as seed resource is deluded. This is obviously a harsh and exposed site that will be difficult to establish any sort of tree cover over the relatively short time passage.

Bryan, have you visited the site? Why wouldn’t the mature pines in the photo and the deciduous trees below produce seed? If you search on my posts on BrewDog and the Lost Forest you will see many examples of natural regeneration across the site. Where I agree with you is that most of the area is harsh and exposed which makes planting trees even more foolish. As I have noted before, none of the isolated pines appeared to have been blown down Storm Arwen and part of the reason for that they have extensive roots. Planting pines close together on mounds is a recipe for windblow.

The BrewDog planting disaster, along with similar schemes elsewhere, will lead to fundamental changes in Scottish forestry policy and its associated financial incentives. It is now obvious that most tree planting today in Scotland is being done in the wrong places. All those individuals and corporate institutions who are driving this planting, almost entirely from far away places, need to read the following statements from the UK Climate Change Committee, published on 26 Feb 2025. In explaining why it is “vital” that the UK needs to increase planting rates to 37,000 hectares per annum it adds the following qualification: “trees are only planted on mineral soils, with organic soils excluded to protect biodiverse habitats and minimise carbon loss from planting disturbance”. And it emphasises that “natural regeneration has significant potential to build carbon via the expansion of trees and scrub across landscapes”. In Scotland this means that tree planting has to shift from uncultivated land in the uplands to mineral soils in the lowlands, along with severe reductions in deer populations to prevent overgrazing. In future the natural regeneration of trees and scrub will be the predominant landscape change in the uplands, not tree planting. Any investor in natural capital who does not understand this is likely to lose a lot of money.

So what would investors do? Buy land and wait for it to regenerate naturally? Would the government pay them for that?

Thanks Lucy. All land requires some form of management, even if that is simply better control of grazing by deer, sheep or cattle etc, along with monitoring of the recovery of vegetation. There are already many types of management agreement in place between landowners and government bodies such as NatureScot, Scottish Forestry and the Agriculture Department which investors can take advantage of, as landowners. Alternatively, some investors are now going into partnership with existing landowners, notably voluntary conservation organisations and/or local community groups, to achieve environmental aims. The key is to be clear what the environmental, social and economic outcomes are to be and how these relate to the investment of private or public funds.

It strikes me that, as often happens, it is the people actually doing the work who cause some of the problem. Tracked vehicles, badly installed and maintained deer fencing, not planting the new baby trees deeply . Targets for planting so each tree has to be planted in too short a time. Not watering the trees as they try to establish themselves. No follow up to maintain the trees or clear up the rubbish left behind. I know nothing of forestry or trees but I work in construction and a bad labourer on a site can cause havoc by putting the wrong sand/cement ratio into a mix or sweeping rubbish under floors cause they can’t be bothered to skip it. This is little different. Mr Watt & brewdog probably want this to succeed so, DOGE yourself and check all the elements of this lost forest planting

You’ve admitted you know nothing of the nature of this type of works but are laying blame upon the employed workforce.

Tracked vehicles – essential for upland operations as helicopter diggers as yet are non existent.

So many jumping on the keyboard here without a clue or real insight following a seriously skewed post.

In my view, this is right, the destruction of the land at Kinrara is not the fault of the people working on ground preparation or planting trees. Most are very poorly paid and the tree planters are expected to plant hundreds of trees a day and have little or not control over what they do. As a result it is not surprising some are not planted properly. This specific problem is caused by the interests that are making money out of the forestry grants scheme and on the backs of the workforce. The wider problem, however, is we should not be paying to plant trees in places like Kinrara

You are right to focus on following the money. There are so many unsuitable subsidised planting schemes around Scotland. The governments have learned nothing from the 70s and 80s planting in the Flow country.