While Dave Morris has discussed Brewdog in a couple of posts (see here) parkswatch has not covered how they have been managing their “Lost Forest” since the end of April (see here). I had hoped to visit Kinrara first to check on how the replacement planting for all the dead trees was going (see here). The two photos here, sent by a reader recently, has prompted this post.

What has BrewDog been doing on the ground?

On 19th April, or thereabouts, James Watt, still then CEO of BrewDog, responded to the “Dead Forest” scandal with a post on Linked In reproduced by many media outlets (see here for example). In it he claimed:

“We have done a full assessment with Scottish Woodlands Ltd and two weeks ago we began replanting the failed saplings in earnest and we have already replaced 50,000 of the baby trees that did not survive the winter.”

While it is true BrewDog’s dead trees did not “survive the winter” that is because most were already dead last summer. This was a result of most of the saplings having been planted on mounds of mostly peat soil designed to dry out…….which they did very rapidly in the drought. Starting to replace then when Spring was underway risked repeating the whole disaster, as I explained to the National in May (see here). Luckily for BrewDog, the wet spring and summer means they may have got away with it.

A further comment from Mr Watt was very revealing:

“One thing that is for sure is that sustainability is hard. Whatever you do, you could do more. Whatever you do, there are critics who love nothing more than to tear it down. Whatever you do, it can feel totally insignificant. And things don’t always go to plan.”

That may be true of business and indeed our personal lives but it is NOT true of nature. Had Mr Watt had any understanding of woodland ecology, taken a proper look at what was happening on the ground or sought advice from the successful restoration projects in the area, he would have realised that far from trying to “do more” the only thing BrewDog needed to do was keep grazing levels low and nature would do the rest.

Those issues are encapsulated in Dave Morris’ photo, published in his July blog, along with his accompanying commentary:

Rather than replant, BrewDog would have been better trying to restore the damage mounding has caused to the soils, which means the scheme will be leaching out CO2 for years into the atmosphere, and leaving vegetation recovery and woodland expansion to natural regeneration. However, had they done this they would have had to repay/risk losing the £1,229,496 grant they had been awarded by Scottish Forestry.

BrewDog don’t appear to have issued any further statements about how many trees they managed to replant after the initial 50,000 but if more replanting is needed now is the time to start doing so. Whatever the reason for the caterpillar track damage in the top photo, however, it was unlikely to be connected with re-planting trees – the vehicle is too big – and more likely to be linked to the peatbog restoration that took place in the vicinity:

Perhaps the vehicle was being used to repair the previous damage done by vehicles in this area? The risk of “doing” is each time you “do more” you risk causing new/more damage and releasing further carbon into the atmosphere.

Meantime, whatever BrewDog are doing on the ground – I will visit this winter for a proper look – one thing they haven’t done, according to the person who supplied the two photos, is to mend the damaged bridge as they had promised.

Brewdog’s withdrawal from carbon offsetting and the Lost Forest

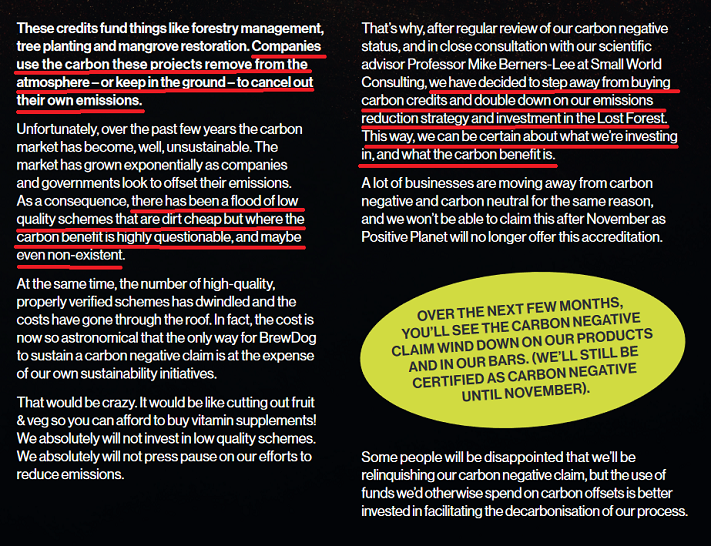

In July BrewDog published an “interim” sustainability report for 2024 (see here). This attracted significant publicitly after they emailed their staff to say they were ‘exiting the carbon credit market’ (see here).

BrewDog’s strategy had been to try and reduce its own carbon emissions as far as possible but then offset the remainder through buying carbon credits linked to initiatives like treeplanting and peatland restoration. The sustainability report explained the reasons for their change of strategy as follows:

BrewDog was quite right to state that the carbon market is flooded with low quality schemes where the “carbon benefit is highly questionable or, maybe even non-existent”. The only thing I might have added is that in Scotland most of these low quality schemes are being largely by the public. BrewDog was also right about the need for businesses to double down on their own emissions.

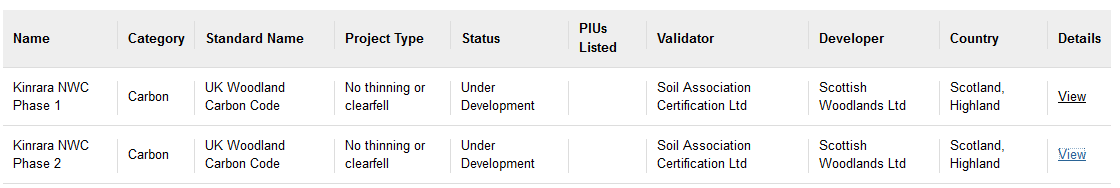

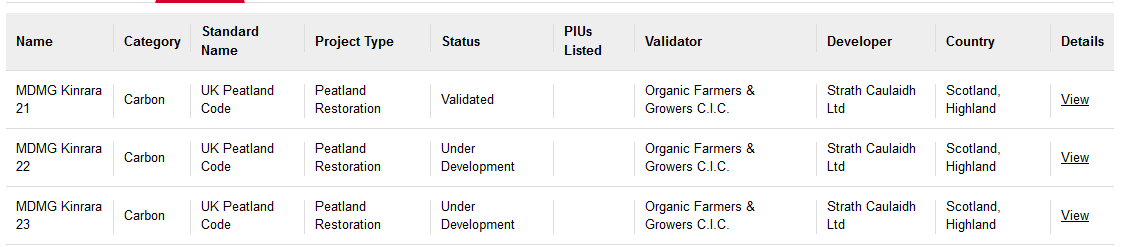

The mote in BrewDog’s eye was their own Lost Forest. This they had claimed to the public would be “sequestering up to 550,000 tonnes of CO2 each year” and used to register five carbon off-setting schemes, two under the Woodland Carbon Code an three under the Carbon Code:

Why, if BrewDog has withdrawn from the carbon markets were its own schemes still registered on the carbon register on 1st Novermber? And what better example of a poor quality scheme than its own Lost Forest where over half the trees planted have died?

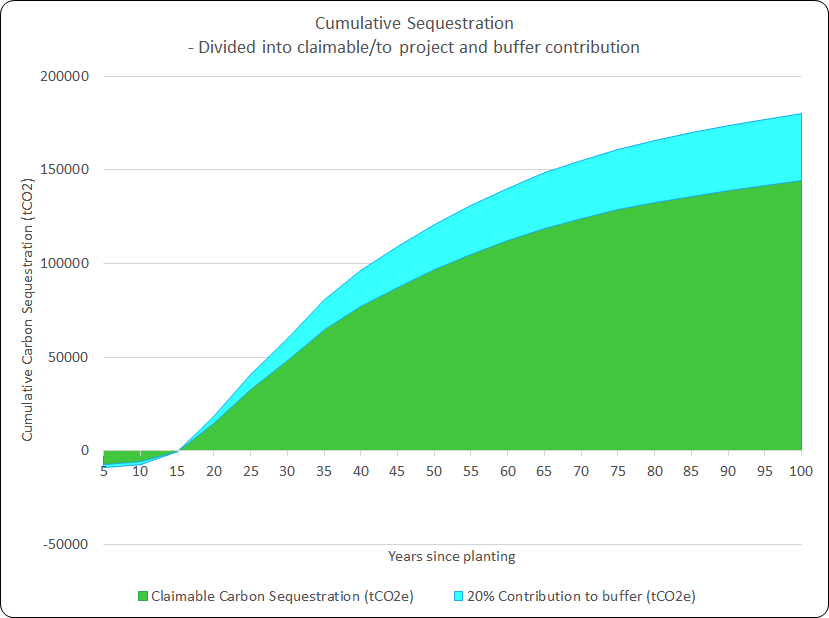

A year ago I argued that the assumptions in the carbon calculation for the Lost Forest Phase I scheme, which predicted that the carbon released in its planting would be recouped by the growth of the trees in 15 years, were highly questionable. Whatever the assumptions, the calculator itself clearly needed to be updated as a result of half the trees dying. That never happened as is shown by the documentation still on the Register, which remains the same as it was before the trees were planted:

This provides a good illustration of a very basic flaw in the Carbon Registry and the Carbon Market.

Under the Woodland Carbon Code (WCC) scheme developers can issue and sell “Pending Issuance Units”, effectively a promise to deliver a Woodland Carbon Unit in future. Had BrewDog issued PIUs – the blank column in the tables above – their value would have been determined by the date at which they were predicted to start producing Woodland Carbon Units, in this case 15 years. For the PIU system to work, potential investors need to be certain about the quality of the schemes – which affects the risks of the trees not growing as predicted – and that they are being monitored properly.

At present validators, in this case the Soil Assocation, first check tree growth after 5 years (and then once every ten years thereafter). For native woodland creation schemes this light touch to validation should not matter too much at first. This is because most schemes are funded by Scottish Forestry, who monitor whether tree establishment rates in the first five years meeting the conditions specified in their contracts. Scottish Forestry also holds overall responsibility of the WCC so is in an ideal position to require any scheme which registers under the WCC updates its carbon calculations on a regular basis to reflect what is happening on the ground.

The first question, therefore, is why Scottish Forestry never required BrewDog or Scottish Woodlands to update the Registry for Phase I of the Lost Forest? The second questions is, given this failure, how can anyone have confidence in the information on the WCC register which is supposed to underpin the market?

BrewDog’s own Lost Forest carbon offsetting scheme therefore provides the perfect example of why it was right to withdraw from buying PIUs and Carbon Credits from other players in the market: no-one thinking of investing in this market can have any faith in what they might be buying.

Investment and Lost Forest Ltd

While BrewDog’s half yearly review said it intended to double-down on its investment in the Lost Forest it did not explain what this meant.

BrewDog owns the Kinara Estate/the Lost Forest through its fully owned subsidiary Lost Forest Ltd. In May and August 2023 Lost Forest Ltd took out two loans from HSBC, one which was secured by a fixed charge over the property and the other by a floating charge over the business as a whole (see here).

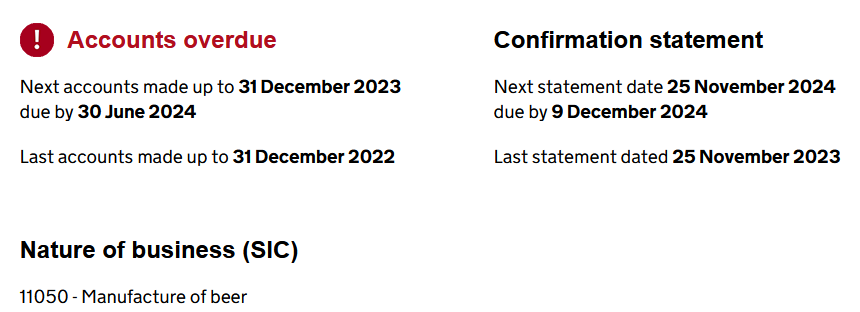

Had the consolidated accounts of BrewDog PLC been published on time (those of Lost Forest Ltd are not due until 31st December) we might now know the value of those loans and the interest payable but those accounts are now well overdue:

The accounts would also show how much of the cash provided by HBSC had been spent last year and how much remained in the business to pay for the replanting of trees or other purposes such as those James Watt mentioned in a blog post June 2023 (see here) : “a hotel built from sustainable cabins, a campsite, a distillery, hiking and biking trails as well as kayaking on the site’s own loch”.

What Companies House does show is that over the course of May/June the existing Director of the Lost Forest, Neil Simpson, resigned and was replaced by three new Directors: Martin Dickie, the co-founder of BrewDog with James Watt , James Arrow, BrewDog’s CEO and James Taylor, the new Chief Finance Officer. Whatever their skills, none appear to have any expertise in land management or native woodland restoration. That lack of expertise might not matter if the Lost Forest Ltd employed a Conservation Manager but its last accounts showed it employed no staff and nothing appears to have changed since then.

The company was created in 2018 as BrewDog Admin Ltd and lay dormant until renamed as Lost Forest Ltd in December 2020. The Articles of the company, which set out how it operates, have never been changed from the Model UK articles:

What this means that conservation, whether absorbing carbon from the atmosphere or restoring nature, does not appear to be core to the purpose of company known as Lost Forest Ltd. Its purely a company, a financial vehicle for doing business on behalf of its owner.

What this means that conservation, whether absorbing carbon from the atmosphere or restoring nature, does not appear to be core to the purpose of company known as Lost Forest Ltd. Its purely a company, a financial vehicle for doing business on behalf of its owner.

What next?

It will be interesting to see if BrewDog’s accounts for 2023 show its started to invest its own money in the Lost Forest in 2023, instead of relying entirely on grants as it had done previously. If not, it will increasingly look like BrewDog was no more committed to conservation when it bought the Lost Forest, than Abrdn was when it bought Far Ralia (see here). What’s more, without investment Lost Forest Ltd will have no means of repaying the loans from HSBC and it may not be that long before BrewDog is forced to follow the recent example of Jeremy Leggett and Highland Wilding (see here) and sell part or all of the land to repay the bank.

It would be interesting to know how Kate Forbes, the local MSP, reconciles any of what has happened at the Lost Forest (or Far Ralia or Highland Rewilding) to date with her recent claim that Scotland is becoming a true global contender in Green Finance (see here)? Perhaps some of her constituents could ask?

Meantime, until I can visit the site, I would welcome any photos of the peatland and woodland restoration schemes on the Dulnain side of Kinrara.

As a point of detail, the naturally regenerated birch trees in your photo will oxidize carbon to the air just as much if not more so than the planted pine. The Friggens et al report published in 2020 suggested that on carbon rich soils (basically most moorland soils), planted trees, do not increase overall carbon stocks on decadal timescales. Actually, about 40 years. There are still many other good reasons for planting or regenerating woodland, but carbon is not one of them, not in the short- medium term anyway when the “emergency” is at its most pressing. Looks like that pine tree should get away OK just now.

You are right about the Friggens report. It showed that trees release carbon from soils in the medium term through processes like respiration and the development of mycorrhizal fungi and this is likely to be than the carbon that is absorbed into wood as the tree grows. This appears to be the case whether trees are planted or regenerate naturally. HOWEVER, there is a further carbon factor that needs to be taken account of in the short term. Forestry techniques like mounding turn the soil over and expose it directly to the atmosphere where it oxidises creating CO2. The native woodland planting schemes at the Lost Forest, Far Ralia, Muckrach etc are therefore responsible for giving a short-term boost to atmospheric CO2. This madness is being driven and financed by the Scottish Forestry grants system and Woodland Carbon Code.

NIck….. birch trees will oxidize the carbon in the soil. Mounding may speed things up a bit, but the result will be the same. As a native woodland advisor who knows that birch is the fundamental building block of just about every other woodland type, I realize that this is a big problem. The science is not marginal, it is clear cut. Scots Pine appears to be less of a problem.

Victor, yes ALL trees will oxidise carbon out of the soil (and also add some carbon to it) over time but I think you are totally underestimating the significance of short-term carbon emissions caused by planting. This is not just about the carbon released by mounding its all the carbon emissions caused by the diggers, transporting trees from nurseries etc. Natural regeneration avoids those emissions and the carbon costs of culling deer to enable that to happen are far smaller. Pine might be better than birch in the medium term when it comes to the carbon balance sheet of carbon absorbed into the trees v carbon released from the soil, but when both Scots Pine and birch are ten are penny trees which would spread over much of Scotland very rapidly if deer numbers were reduced, it seems to me there is no excuse for planting them.

Mounding is just the most horrible way of establishing woodland.

Did a bit in some post harvest woodland here on recommendation of woodland company.

After first bit said naw, looks awful encourages weeds and impedes walking in the woods.

Success replanting rates are slightly lower but less evasive whins etc spring up and dominate areas.

I cycled the Burma Road last week and, after following this story for a wee while, I was surprised by the lack of saplings on the Kinrara side given the level of planting claimed by Lost Forest.

On the climb I overtook a mechanical digger crawling uphill, preceded by an escort vehicle. Destination unknown – it was too cold to hang about for long to find out. The bridge is still damaged.

The Dulnain side has a sprinkling of natural regrowth Scots Pines, as well as a few mature trees closer to the river. Down in the strath, it looks as if there has been some natural regeneration over a long period of time but I don’t know if that is part of the Kinrara Estate.

Just like their beer. STYLE OVER SUBSTANCE.