In the lead up the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) board meeting on 16th September which is due to decide the Flamingo Land Mark III Planning application (see here), I thought it would be worth trying to tell the whole story. Its a long one, so the first part was about the LLTNPA’s direct involvement with Flamingo Land (see here): from working with Scottish Enterprise (SE) to sell off the West Riverside Site; through helping to appoint Flamingo Land; to how staff offered up the land the National Park owned for the development; and then the subsequent cover-up.

This second part takes a broader look at how the LLTNPA has managed the wider planning system to help deliver the Flamingo Land development which doesn’t mean to say it will in two weeks time. Tat now depends on the political wind but whatever staff recommend and the board decidedes needs to be viewed in the light of the history.

History of the site prior to the creation of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park

In 1609 King James granted by Royal Charter to the Burgh of Dumbarton and its successors the whole of the River Leven, together with fishing and access rights, from Balloch to the Clyde. The original purpose of the charter was to stop flooding in Dumbarton, an issue that is still pertinent today with Flamingo Land wanting to erect chalets on part of the West Riverside site that has once again been classified as flood plain.

What happened subsequently has recently been described in a response from the Registers of Scotland to Marie McNair, the SNP MSP for Clydebank and Milngavie (she was asked by her of her constituents):

“notwithstanding the fact that the 1609 Royal Charter to the predecessors of WDC [West Dunbartonshire Council] conveyed to them the River Leven, a separate route of title was created at some point in the 18-20th centuries as a result of the Colquhoun of Luss mistakenly believing the river to fall within the Luss Estate title. A number of titles to parts of the river were sold off from the Luss Estate and recorded in the Register of Sasines, and it is these titles from which the Scottish Enterprise title (and others) derive.”

“It is important to note that despite the titles deriving from the Luss Estate being founded on deeds from someone who was not the owner of the river, Scots law (under the doctrine of prescription) allows these deeds to form the basis of good title if the subjects are exclusively possessed for a defined period of time following recording of a deed. In addition, we also note that the title in question was previously owned by British Railways Board who subsequently conveyed to the Scottish Development Agency. It is therefore likely that regardless of the historical ownership position, the statutory powers associated with railways taking title to land would have put the position beyond doubt anyway”.

Whether you believe Colquhoun of Luss mistakenly thought the river was theirs or stole the land is immaterial. Under Scots Law they established title through possession (as they did for much of the land they used to own around the south west of Loch Lomond. There is no need to go through that history. The key events for the purposes of this story is that first in 1989 the Scottish Development Agency, Scottish Enterprise’s predecessor, purchased the “area of land immediately east of Pier Road to the River Leven (including the building that houses the Tourist Information Centre), and up to the roundabout adjacent to Pier Head (boat & trailer park)” from British Railways Board for £180,000. That land is now known as the West Riverside Site.

Then, in 1995, a second larger area of land between Drumkinnon Bay, Old Luss Road and Pier Road, which included Drumkinnon Wood, was purchased by Scottish Enterprise for £2,600,000 from the Drumkinnon Development Company Limited.

The response from the Registers of Scotland to Marie McNair MSP explains how Scottish Enterprise then secured title to the River Leven:

In 1990, Scottish Enterprise registered title to part of the river, which had the effect of transferring the subjects from the older Register of Sasines to the more modern, map-based Land Register. Registration occurred under the previous legislative regime governing land registration in Scotland, the Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979. Registration under this Act had the effect of making any title ‘good’, even where the underlying deeds were uncertain (the so-called ‘Keeper’s Midas Touch’). Rectification of such a title (to instate the true owner as registered proprietor) was only possible if it could be demonstrated that the registered proprietor was not in possession, which was often difficult to evidence, particularly in respect of bodies of water (this is what is alluded to in para 3.3 of the Council report).

Although the current legislation on Land Registration in Scotland, the Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Act 2012, removes the Midas Touch for new registrations, rectification of titles created under the 1979 Act fall to be handled under transitional provisions which effectively recreate the ‘proprietor in possession’ test under and, in fact, create a statutory presumption that the registered proprietor (SE) is in possession, which must be rebutted in order to rectify. The Keeper can only rectify a title where the purported inaccuracy is clear and beyond reasonable doubt – she has no power to arbitrate in disputes and nor can she make decisions of a quasi-judicial nature where there is uncertainty in the title position. Given the nature of this particular issue (and in particular, that is seems likely that the SE title has been made good either by historical possession or by acquisition by the Railways Board).

SE has until now kept most of the land they acquired in Balloch. Their biggest disposal was in March 2001 when they sold Keir Homes a large parcel off Balloch Rd for housing for £2,075,000. That is now known as Drumkinnon Gate. They has previously sold a plot of land by Balloch Bridge to Sweeney’s boatyard for £85,000 in 1998. A later attempt to seek planning permission for housing on the overspill car park, presumably with the intention of selling it, was withdrawn in 2008 (see here).

Other land SE owned at Balloch was developed through leases, most notably in the case of Loch Lomond Shores, the retail/leisure development on the south of Drumkinnon Bay which was granted a 150 year lease in 2001. It opened its doors in 2002, the same year as the National Park came into existence.

Apart from a few relatively minor planning applications, some of which were implemented and some not, most of the rest of the land remained undeveloped and the situation in Balloch in 2002 more or less the same as it is today. While SE had made an attempt to in 1991 to build a hotel and marine/leisure facilities near the pierhead, this was refused in 1992 (see here) – that is 33 years they have now been trying!

History of the West Riverside site following the creation of the National Park

While unable to change anythng which preceded them, the creation of the LLTNPA offered a major opportunity to influence and determine how the undeveloped land SE owned at Balloch should be used in future. What sort of gateway was fitting for a National Park? With one of the primary intentions being that Scotland’s two new National Parks would change how the planning system operated in their areas so it was brought into line with their four statutory aims (conservation of the natural and cultural heritage; public enjoyment of the special qualities of the area; sustainable development; and wise use of resources) hopes among some were high..

Unfortunately, the LLTNPA has removed from the internet all records of what it did or discussed in its early years and exactly why all new development on SE land came to a halt for a few years merits further investigation.

I have learned enough, however, to believe that many on the LLTNPA Board in its early years were not exactly supportive of SE’s intentions, which were to cram as much development as possible onto the site. The board though faced significant constraints because the LLTNPA was dependant on SE for office accommodation at the Gateway Centre.

As importantly Lomond Shores soon got into difficulty: Drumkinnon Tower had to be re-purposed in 2005 (see here); concerns emerged about the amount of public money being handed to private business (see here); and like other property businesses it began to change hands – and has continued to do so (see here). There were possibly sufficient problems at Loch Lomond Shores to divert SE’s attention from developing the West Riverside Site – but those problems also should have taught both SE and the LLTNPA some lessons.

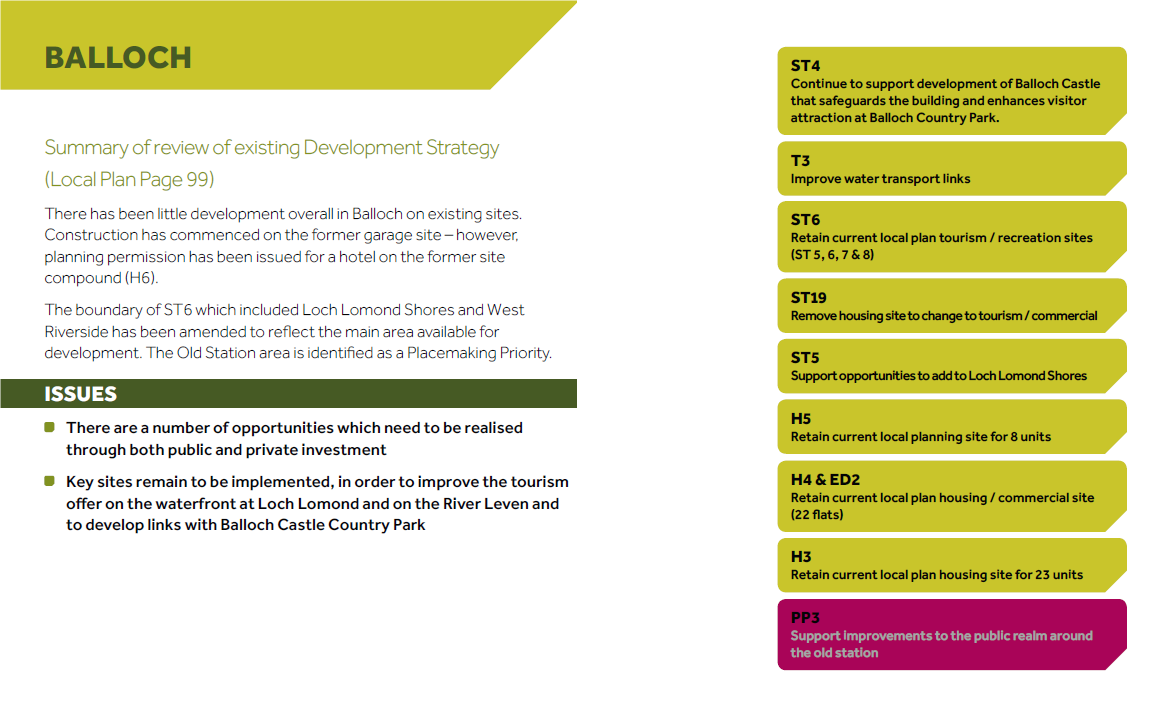

In 2008 Fiona Logan became Chief Executive and, as I explained in the first part of this post, re-oriented the LLTNPA into a far more commercial direction. This was in time to influence the LLTNPA’s first Local Plan, which took seven years to develop and was approved in 2010. That plan is one of the many LLTNPA documents that has been completely removed from the internet but there is some information about, in the Main Issues Report (MIR) for the subsequent Local Development Plan:

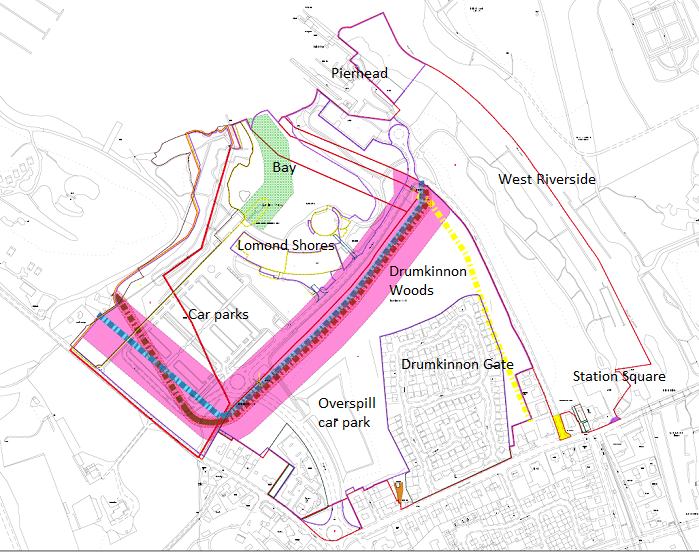

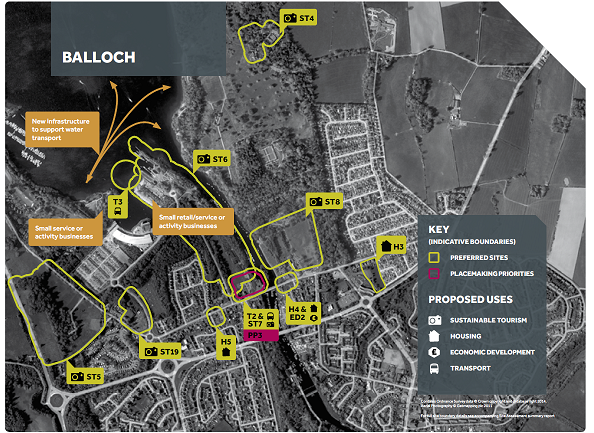

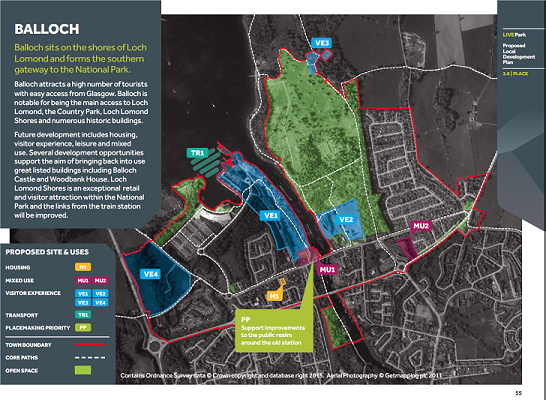

The MIR map for Balloch shows that most of SE’s West Riverside Site, along with land the LLTNPA owned at the pierhead, had been allocated for Sustainable Tourism in the Local Plan. The brown tab suggested that the pierhead area should be for “small retail//service or activity businesses” – quite a contrast to the proposed “£40m” Flamingo Land deveopment.

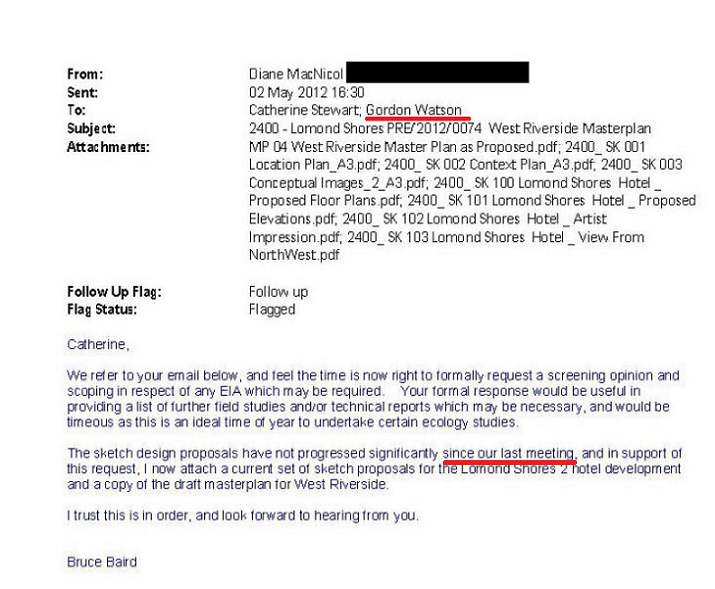

The brief explanation and key accompanying the map also explained that the LLTNPA were proposing to amalgamate what had been classified as four separate tourism and recreation sites in the local plan (ST 5,6,7 and 8) into one site (ST6). The significance of the change was not explained but it followed a scoping request (see here) for a masterplan to cover the whole site that was submitted to the LLTNPA in 2012:

The email from the application suggests LLTNPA staff had had several meetings with SE’s agents. The plans included a large hotel on Drumkinnon Bay:

and an outline plan for the land:

I have been unable to find out if there was ANY consultation on this masterplan locally but from reading the MIR one would have no idea that a development of this size and character was what was meant by “Sustainable Tourism”. The then Balloch and Haldane Community Council (BHCC), a statutory consultee, certainly didn’t know what was meant:

The BHCC response helps explain why there were almost no other responses to the MIR consultation from the general public in Balloch – no-one knew what it meant!

In October 2014 a report was presented to the LLTNPA Board on the MIR consultation, branded “Live Park”, by Gordon Watson (see here). After stating the MIR “is the principal opportunity to consult with stakeholders on the Plan’s proposed content and involve the wider public” the report went on to claim:

“The investment of significant time and resources in early engagement to help inform the preparation and content of the Main Issues Report, through our programme of charrette [planning consultation] events and workshops, has delivered several demonstrable benefits, most notably fewer responses when compared to the past Local Plan consultation and a smaller number of contentious issues or sites.”

The fewer responses in Balloch certainly weren’t down to greater engagement – there was no charrette – and the report went on to contradict this: “Callander, Arrochar/Succoth/Tarbet areas were proposed as the main areas for change in the new Local Development Plan very much reflecting the recommendations from the charrette events in these areas”. Despite being known as the gateway to the National Park there was no mention of Balloch in the entire report. Strange!

In April 2015, at the special board meeting which also approved the camping byelaws, the LLTNPA approved the draft Local Development Plan (LDP) which had arisen out of the MIR for public consultation (see here). It was in March and April 2015 (see here) that planning staff from the LLTNPA had been working with SE on the marketing of the West Riverside Site for sale – there was no mention of this in the board papers.

The main changes in the LDP from the proposals in the MIR for the West Riverside Site were that the term “Sustainable Tourism”, which at least could be related to the statutory aims of the National Park, had been changed to Visitor Experience and the West Riverside Site, instead of being labelled ST4 had become VE1. The term Visitor Experience was extremely vague and the draft LDP contained no further information on what was being proposed. Transport Scotland expressed the problem succinctly in their response:

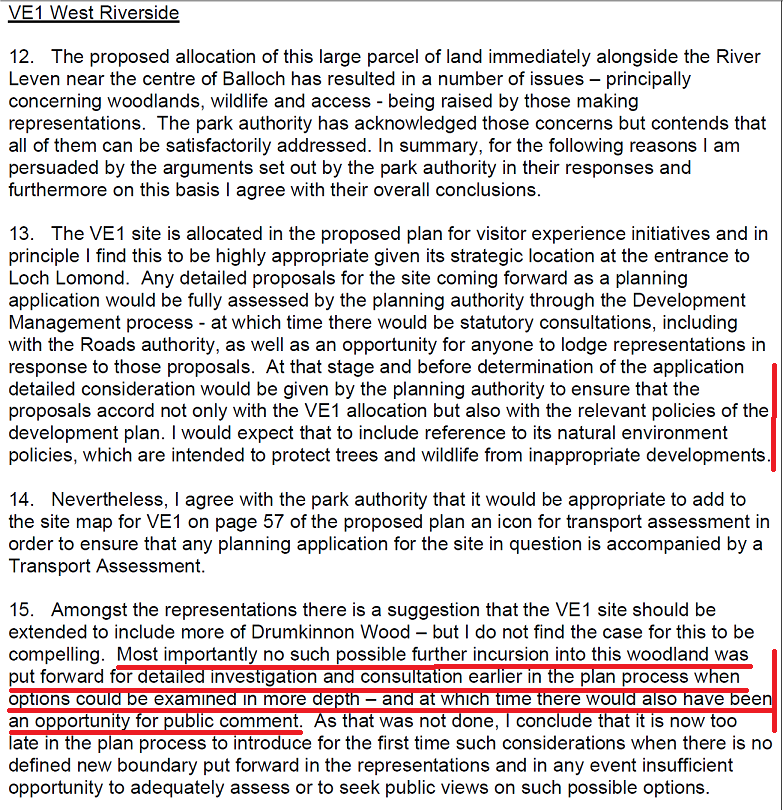

The lack of any information about what was being proposed would explain why Transport Scotland’s was one of ONLY three responses to the VE1 proposal. One of the others was from SE proposing to extend the VE area into Drumkinnon Wood – luckily a local person spotted this and forcefully objected..

By the time the LLTNPA Board was asked to approve the LDP in October 2015, staff clearly knew what was likely to be “entailed” by VE because they were on the interview panel which recommended Flamingo Land’s appointment as preferred developer in August 2015 and someone called “Stuart”, who appears to be Stuart Mearns head of planning, had attended a meeting with SE on 30th September 2015 to discuss how to progress the development. There was nothing in the board reports about what was clearly being planned behind the scenes.

Although planning staff did recommend their board reject SE’s proposal to extend the land allocated for development into Drumkinnon Woods, had they not there would have been uproar. More significant is the fact the Flamingo Land included Drumkinnon Woods in their first planning application in 2018 amd clearly has been led to believe that staff would not reject development there out of hand whatever the LDP said.

The draft LDP then went to the Scottish Government’s reporters for consideration. It took from between January to September 2016 for them to complete their inquiry and their final report, which is very thorough, was published on 4th October 2016:

It appears from this that the Reporter had only the vaguest idea of what sort of development might be proposed fo the West Riverside site too! The reporter’s reasons for rejecting SE’s last minute suggestion that VEI should be extended to include Drumkinnon Woods could, in retrospect, be judged equally applicable to the rest of the West Riverside site! . The public had been given no opportunity to examine “in more depth” the option which the LLTNPA and SE had been developing behind the scenes

What this part of the story shows is that LLTNPA staff managed the whole LDP process so that people knew as little as possible about what was being planned for Balloch. Having got the land allocated for meaningless visitor experience, it opened the door to Flamingo Land.

The LDP was originally intended to cover the period from 2015-2020, following on from the Local Place Plan 2010-15, but was only approved by Scottish Ministers at the end of 2016 and for the period 2017-21. Covid and the adoption of National Planning Framework 4 then intervened but the LLTNPA only started worked on a Main Issues Report for its next LDP this year. So far there has been no public consultation.

Had public consultation started, thousands of those who have objected aganst the Flamingo Land planning application (objections have now topped 150,000 (see here)) might have challenged the allocation of the whole of the West Riverside Site for Visitor Experience or demanded the LLTNPA be much clearer about what this might entail and what was acceptable and what not..

The fact that public consultation on the new MIR will only take place after the Flamingo Land planning application has been determined in principle is another bit of timing which needs to be explained.

While the LLTNPA board have no choice under planning law but to treat the allocation of the West Riverside Site for Visitor Experience as a “material reason” for supporting the application, they should be mindful of how the staff who will likely be presenting the report to the meeting, Gordon Watson and Stuart Mearns, got the National Park into this position.

Sidelining the local community

I have explained previoulsy how, after its Board approved the LDP in October 2015, LLTNPA staff organised a planning charrette for Balloch (see here). While other local communities in the National Park got their charrettes BEFORE the LDP was agreed, Balloch got their charrette afterwards.

The Balloch charrette took place between January and May 2016, in the year between LLTNPA and SE deciding to appoint Flamingo Land as preferred developer for the West Riverside Site and when they made this public. The dates are important because much of the charrette, financed by the Scottish Government, was concerned with engaging the local community about the West Riverside Site who were kept in the dark about what had been agreed.

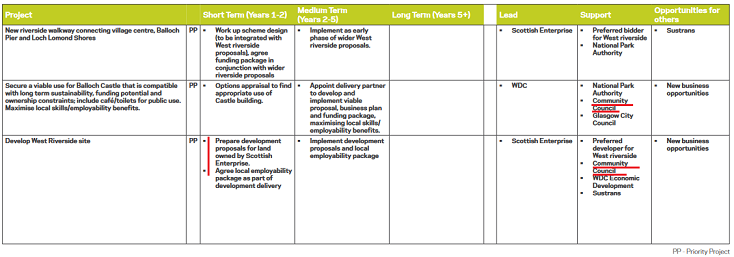

The charrette final report (see here) contained a list of actions:

Perhaps when the consultants who conducted the charrette suggested the project “prepare development proposals for land owned by Scottish Enterprise” they too were unaware that SE and LLTNPA staff had already been doing this?

While the Community Council was listed under the support column for several actions (developing proposals for Station Square, Parking Strategy) it is unclear how many of these were actioned by Flamingo Land before they submitted their first planning application in 2018 (see here).

As importantly many of the ideas that had been suggested at the charrette – the longstanding wish for a pedestrian bridge over the River Leven at the pierhead to connect with Balloch Country Park and the Riverside walkway – were either never included in the list of projects or never actioned (see here).

SE signed a legal agreement with Flamingo Land on the 13th September 2016 (information obtained through an FOI request) which appear to have included the Exclusivity Agreement. Under this SE undertook to sell the West Riverside Site to Flamingo Land should they obtain planning permission. It was designed to make it very difficult for the local communityto propose any alternatives for the site or to make use of the new rights created by the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015.

When Flamingo Land withdrew their first planning application in 2020, after public pressure had forced LLTNPA staff to (narrowly) recommend its refusal, instead of engaging with the local community – as intended by the Scottish Parliament under the new legislation – SE renewed its EA with Flamingo Land (see here). The LLTNPA kept silent, despite its legal duty to promote sustainable development of local communities.. The Scottish Government, despite the many soundbites by Ministers about supporting and empowering local communities, has since allowed SE to convert that EA into conditional missives . The appear to have been designed to shut out the local community even further (Ross Greer MSP obtained a copy through an FOI request and the only sections that are not heavily redacted concern those that are about excluding the local community!)

Since 2020 the LLTNPA has, in response to Scottish Government policy, undertaken a number of initiatives designed to increase community involvement in planning. In June 2023 (see here), the LLTNPA Board considered two papers about tourism infrastructure in the National Park. Despite Stuart Mearns, Director of Place, having described Balloch as “the main visitor and transport interchange for the National Park” and despite the LLTNPA having identified the need to address transport and parking issues and for a masterplan for the pierhead area, work on projects was descibed as “deferred”. While no explanation was given, the delay has allowed the Flamingo Land Planning Application to be decided first.

More recently the Board Meeting on 24th June 2024 considered an update to their Place Investment Strategy (see here):

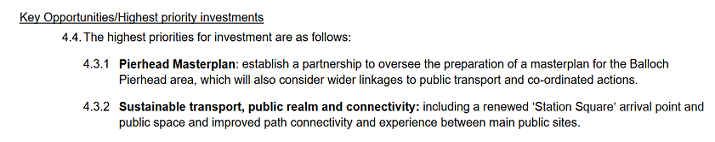

Suddenly, with the Flamingo Land determinating hearing about to be announced, there is action! Appendix 3 to the report describes Balloch as “a Priority Area” and, out of the three priorities for investment identified, two have considerable significance for the West Riverside site:

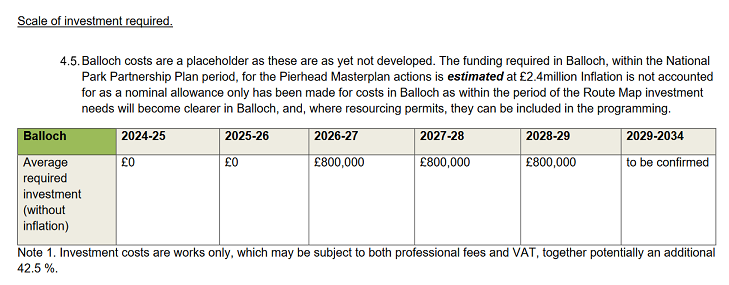

The board paper also stated that £2.4m would be needed to finance the masterplan at the pierhead:

This masterplan presumably includes the area at the pierhead where Flamingo Land is wanting to build an aparthotel and leisure complex. If so, is part of the £2.4m another public subsidy for private development on land currrently owned by the public? Is this a repeat of what happened at Loch Lomond Shores? Even more importantly, how does the LLTNPA know delivering a masterplan at the pierhead will cost £2.4m when work on it has not started? Or has everything, as per the rest of the West Riverside Site, already been decided behind the scenes by staff?

What this tells you is that the LLTNPA has not changed iand is still trying to exclude the local community from plans. The LLTNPA’s commitment to find £2.4m to invest in the area, however, at last offers an opportunity from a community perspective. If the new South Loch Lomond Community Development Trust now registers an interest in taking over or managing the land which the LLTNPA owns and leases at the pierhead, they should now be able to call on the LLTNPA to secure the £2.4m to fund any proposals they develop! Together with any new funding stream for outdoor education (see here) that could make a community watersports hub financially viable and offer a real alternative to Flamingo Land

The current LLTNPA Board and the Flamingo Land planning application

There is a line between what a planning authority needs to do to enable sustainable development to take place (setting the parameters for development, engaging local communities, advising potential developments etc) and backing a particular developer or development. Scottish planning policy requires that after setting the framework for developers, planning authorities need to decide individual planning applications objectively according the spatial allocations in their LDP and planning policy (both local and national).

Throughout the Flamingo Land saga the LLTNPA Board has shown almost no awareness of this line as I showed in part 1 of this post. Not only have they failed to ask, but they have also refused to investigate their staff’s involvement in the appointment of Flamingo Land and subsequent cover-up or how land owned by the National Park was included in Flamingo Land’s first planning application. Nor has the Board considered how other decisions they have made, such as trying to hand the Gateway Centre back to Scottish Enterprise or agreeing in principle to find £2.4m for the pierhead, might play into Scottish Enterprise’s and Flamingo Land’s interests.

Given this lack of awareness it is hardly surprising that the LLTNPA board has never once questioned how the whole development planning process in Balloch has been managed. Despite Gordon Watson’s recent claims that the LLTNPA have been following planning rules to the letter, last year he once again led the LLTNPA board completely over the line in its new National Park Partnership Plan (NPPP). The draft NPPP approved at the board meeting on 13th March 2023 (see here for papers) included this paragraph:

”Significant new development is not envisaged to be required beyond that already identified in the current National Park and already in the pipeline for delivery. Development that will meet the strategic needs of the National Park and adjoining areas at Balloch and Callander is still considered necessary, as well as a focus on addressing vacant and derelict sites at Arrochar and Tarbet.”

This committed board members to the development in the pipeline at Balloch, i.e the Flamingo Land planning application, as being “consider necessary”. No board members raised questions or concerns about how this might prejudice their ability to take an objective view on the planning application. How can anyone take an objective decision on the merits of an application which they have already decided is necessary?

In the final draft of the NPPP considered by the Board on 11th December 2023 (see here) the paragraph had been amended by staff – there had been no objections to the NPPP on this point – to read as follows:

“There continues to be considerable development interest in the Park, mainly for housing and tourism-related developments, however some places do not have capacity for more development due to environmental constraints or lack of rural infrastructure. Beyond what has already been identified in the current National Park Local Development Plan and is already in the pipeline for delivery, it is not envisaged that any significant new sites for development will be needed in the period of this Plan.”

It appears some had realised the phrase “consider necessary” had stepped over the line. At the same time they removed four out of the five references to Balloch that had appeared in the draft NPPP. While this helped obscure the meaning of the reference to developments “already in the pipeline for delivery”, that could only be a reference to those at Callander and Flamingo Land. Having approved a plan that endorses the Flamingo Land application as being in the pipeline for delivery, it is impossible for board members to take an objective decision about it – at least without a public apology and mea culpa.

Its worth comparing the new NPPP with what was said in the 2018-23 NPPP. In respect of Balloch it stated “Support village centre and station square public realm improvements; Encourage ‘charrette’ vision; Support Balloch Castle and Country Park regeneration/improvement”. It was far less specific and there is not commitment in that plan to delivering developments “in the pipeline”.

The BHCC has written to individual members of the LLTNPA drawing attention to this, so they cannot say that they don’t know, and has called for the board meeting scheduled for 16th September to be deferred.,

Development rights over the River Leven

I will end this story by considering another matter that is extremely pertinent to the Flamingo Land planning application and of particular interest to boating interests and watersports.

While Scottish Enterprise’s title to the land at Balloch has never been challenged, that is not the case with the River Leven. Since acquiring the title to the Riverside Site SE had never shown much interest in the river and left it to West Dunbartonshire Council to manage, including dealing with problems such as sunk and abandoned boats. That led to negotiations to transfer the title to the River Leven back to WDC. However, as the subsequent Committee Report to WDC in 2007 (see here) explained, those negotiations fell through – almost certainly because SE realised they were sitting on a potential goldmine which would significanty increase the value of the West Riverside site.

WDC considered legal action but, for the reasons explained above by the Registers of Scotland, decided that was unlikely to be successful and would be extremely costly. They therefore abandoned the legal challenge. That should have been the time for the Scottish Government to step in and tell SE to transfer the land back voluntarily to the people of West Dunbartonshire. But the Scottish Government failed to act and SE, after appointing Flamingo Land as preferred developer, included the rights to the River Leven in their Exclusivity Agreement.

Ownership of the rights to the River Leven is extremely attractive from a private developers perspective. At present, the boat clubs pay relatively little and, with no other public moorings around Loch Lomond, Flamingo Land is potentially acquiring a lucrative. While they have been forced to allay public concerns, “promising” to maintain current arrangements, their promise has no legal basis. If they were serious about it they could now enter their own exclusivity agreement legally binding them to transfer those rights back to WDC once they acquire them from SE – the fact that they haven’t should tell all the boat clubs what will happen if the Flamingo Land development goes ahead.

The rights to the River Leven are crucial for outdoor recreation purposes and the LLTNPA has both a statutory duty to promote public enjoyment of rivers and lochs and a duty protect access rights. Had it called on SE to transfer the river back to the people of West Dunbartonshire that might have made a real difference, but it didn’t.

Instead, the LLTNPA has allowed the rights that were granted under the Royal Charter to be further eroded. As the WDC Committee report points out, there had been considerable public concern about SE selling part of the land along the River Leven to Sweeney’s boatyard. The subsequent blocking of the right of crossing by Balloch Bridge – a right which could not be extinguished by the title to the land being transferred – has never been challenged by the LLTNPA.

A final thought

Its over ten years since I set up Parkswatch, in response to the corrupt processes that led to the camping byelaws. In retrospect it didn’t really matter what I or others such as Chief Inspector Kevin Findlater uncovered or said, the LLTNPA simply brazened it out. They were accountable to no-one.

There are in my view many similarities between how the LLTNPA handled those processes back and how they have been trying to handle the Flamingo Land development. Little has changed in ten years. But suddenly things feel different: 150,000 objections; politicians from all political parties speaking out; and above all a local community that is not just upset but getting organised.

This is about more than the Flamingo Land planning application, its about a National Park Authority that is starting to unravel and that presents major opportunities to reform not just the planning system in our National Parks but the whole way they operate.

You, as others, misunderstand possession alone leading to Title. It does not. Luss, first, registered a Title which on the face of it was valid. This was easy a long, long time ago. It is not easy now. The open possession merely allows them to obtain Title after a period should someone else have a competing registered Title which, also, on the face of it is valid. The openness is important: the “other” Title holder can see this and take action.

Possession-alone leading to Title is English law, not Scots law.

And Scotland is not a biscuit tin: our land has, is, and will continue to evolve