One might have hoped that the controversy caused by the office-bearers of the Royal Scottish Forestry Society to try and sell of what was supposed to be a forest for a thousand years at Cashel (see here) and (here) might have caused the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) to reflect on the public interest. This is not just a matter of protecting all the public investment that has taken place at Cashel over the last 25 years, it is also about how the proposed sale might affect the extensive attempts to improve conservation management along the eastern shore of Loch Lomond.

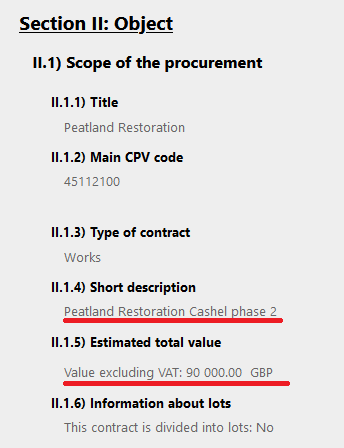

Instead, however, the LLTNPA is rushing ahead to hand the Cashel Forest Trust trustees another £90k in public money for peatland restoration before the proposed sale goes through. In doing so they they will be inflating the land-price and benefitting private investors, just as Scottish Forestry has done at Far Ralia (see here).

The Phase 2 Peatland Restoration at Cashel

Scottish Natural Heritage/NatureScot oversees the Scottish Government’s £250m peatland restoration programme but in our two National Parks this is managed by our National Park Authorities. Information on the Scotland Contracts Portal shows that NatureScot were involved in the decision to press ahead with Phase 2 of Peatland Restoration at Cashel despite the proposed sale:

NatureScot’s Prior Information Notice of 24th July has now been withdrawn but included the documentation in the contract advertised by the LLTNPA on 1st August.

The background section in the LLTNPA’s Statement of Requirements document includes the following:

“Cashel Estate is currently on the market. Cashel Forest Trust and LLTNPA are committed to the peatland restoration project and intend that all peatland works are completed and signed off before the estate is sold. As such, there is a hard deadline of 19 December 2024 for all works including snagging and final checks to be completed by (see Section 5).”

In other words the LLTNPA is fully co-operating with the sale. A National Park worthy of the name might have put the whole project on pause and asked the Cashel Trust trustees to think again in the public interest.

That, however, might have interfered with the Scottish Government’s peatland restoration targets.

The Scottish Government is also indirectly involved in this case through Dr Peter Phillips, their head of Natural Capital Land Management who is a trustee of the Cashel Forest Trust and not just in an advisory capacity. The LLTNPA’s contract documentation shows there will be a site visit for potential contractors on Tuesday 13th August but:

“Alternatively, if you wish to access the site independently at another time please contact Peter Phillips, Cashel Trustee at: peterphillips1603@gmail.com………………………….”

Peatland restoration and the price of land at Cashel – another financial bubble?

The Scottish Government along with its agencies and non-departmental public boards have been putting a lot of effort into trying to create a carbon markets to attract private finance to restore and manage peatland. A report last year for the Scottish Govenment by Finance Earth (see here) – (NB Scottish Government lead Peter Phillips!) – showed the investment wasn’t materialising:

“At current market carbon prices, peatland restoration projects are not viable without partial (and typically substantial) public funding or private forms of grant funding.”

Instead of re-thinking its whole approach to “natural capital”, the Scottish Government continues to hand over signficiant amounts of public money to city interests. The only justification for publicly funded pump priming of the peatland market, as at Cashel, is if the Pending Issuance Units and Carbon Credits this generates were then to produce sufficient income to manage the peatland appropriately. Given the high degree of involvement from the Scottish Government’s head of Natural Capital Land Management, Peter Phillip, Cashel provides a test case for that. That even Mr Phillips appears incapable of extracting conservation income from Pending Issuance Units and Carbon Credits, which would have obviated any need to put Cashel up for sale, provide strong evidence that trying to create a market to restore and manage peatland is never going to work.

Instead, Scottish Government funding for peatland restoration – like tree planting – is serving to fuel land speculation. The process is illustrated by Goldcrest’s sales brochure for Cashel:

In partnership with NatureScot and LLTNPA, grant funding from Peatland ACTION aided the restoration of around 80 hectares of degraded peatland during “Phase 1” works in early 2024. A further circa 140 hectares of Peatland ACTION funded restoration work – “Phase 2” – is scheduled to start in September 2024. The current peatland restoration project at Cashel is estimated to yield around 33,000 tCO2e in emissions reductions. The project is currently in the final stages of

Peatland Code “Project Plan Validation” and is expected to result in around 28,000 tCO2e of claimable emissions reductions (after deductions for the Peatland Code risk buffer). This will correspond to around 28,000 Pending Issuance Units (PIUs) which are expected to be issued later in 2024, and will be included in the sale of Lot 4.”

Lot 4 is on the market for £2,250,000.

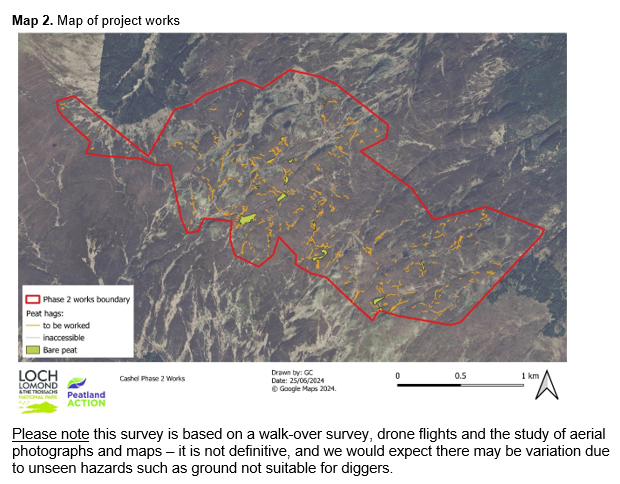

LLTNPA staff’s contract documentation for the Phase 2 peatland restoration is extremely thorough, with lots of photos (see here), video fly-overs of the site, a detailed specification of the work to be done (filling in drains, reprofiling hags and restoring areas of bare peat) and important background information:

“Historic over-grazing and climatic change across the whole site has caused the peat in the Phase 2 works area to become degraded, forming hags and bare peat pans. Prior to the acquisition by RSFS the estate had been sheep grazed but these were taken off in 1996. As a result, some peat hags are beginning to recover naturally where they are not undercut with water in gullies: the reduction in grazing pressure has allowed vegetation growth on the edge of the hags to develop and start to grow over the bare peat hag faces.”

The documentation also rightly states that:

“Before restoring any site, the reasons for peatland erosion need to be assessed and addressed. At Cashel previous high levels of grazing animals would appear to have been a contributory factor”

before wrongly, in my view, concluding;

“This level has been lessened with the removal of sheep numbers and better deer management, and so restoration can be undertaken.”

While the photos show the erosive action of water and frost heave, which is thought to prevent vegetation getting established on bare peat, they also show lots of animal footprints:

There is no attempt in the contract documentation to assess the continued impact of grazing animals and how this might affect the outcome of the proposed restoration and no mention at all of the sitka which are spreading all over the hillside as a result of the reduction in grazing levels:

Cashel – time to reform peatland restoration

While generally by far the most effective way to expand woodland in Scotland is to reduce grazing levels and then let natural regeneration takes its course – even if it results in some peatland being colonised by trees and releasing carbon from the soil – there should be some exceptions for non-native species like Sitka.

At present there is a large-scale conservation project to remove non-native conifers from the east shores of Loch Lomond and restore native oak woodland. Removing sitka from the lower ground while letting it spread over the higher ground, as grazing levels reduce, makes no sense from a woodland perspective and is storing up problems for the future (as the trees on the hill will produce seed which will then threaten the natural integrity of the oak woods). Ignoring the sitka makes even less sense when the public are paying to restore the peatland on the higher ground.

The LLTNPA should have been saying all of this, loud and clear and considering how the sale of Cashel could affect wider conservation objectives in the area. As a minimum it should have refused to fund the Phase 2 Cashel peatland restoration project – and others like it – without a long-term plan to control the invasive sitka and grazing animals. I suspect the staff working for Peatland Action know this but they are not allowed to say so because it would set back the Scottish Government’s peatland restoration targets still further. Meantime, the one LLTNPA board member who has real expertise in this and might have prompted a re-think, Richard Johnson, has declared (see here) that his business, MNV Consulting, was awarded a peatland restoration contract last year at Glen Finglas in the Trossachs part of the National Park. Money not only speaks louder than words, it silences criticism.

The fact that the Cashel Forest trustees are taking the money without putting in place any mechanisms to ensure their land is properly managed after its sold is just cynical. The whole point of the voluntary sector is to challenge what government does and offer an alternative to the private sector, not join the government and private sector gravy trains.

The photos for the Phase 2 Cashel Peatland Restoration project help show how over-grazing damaged peatland at Cashel and how reduced grazing levels are now enabling some of it to recover naturally, while at the same time creating new risks in the form of regenerating sitka spruce. The implication is that most of the bog would have recovered naturally in time if grazing levels had been kept low.

This suggests that instead of forking out large sums of public money in grants for short-term restoration projects and trying to create carbon markets the Scottish Government would be far better redirecting its resources towards reducing deer numbers to 2 km or less (numbers on east Loch Lomond have been far in excess of that) and paying landowners to weed out non-native trees. In short, the Scottish Government and its agents, NatureScot and the LLTNPA, should have awarded the Cashel Trust £90k to do just that, on condition they kept the land and managed it in the public interest.

The LLTNPA would never do that, however, because it always puts private interests first. There are strong parallels between Cashel and Balloch where the LLTNPA raised no objections to Scottish Enterprise selling off public land cheaply, sat on the interview panel that appointed Flamingo Land as preferred developer and has never offered any meaningful support to the local community. How the LLTNPA has bungled Cashel is another reason why we need a proper review of National Parks before the Scottish Government creates a new one down in Galloway.

Excellent analysis of what is really happening here at Cashel and elsewhere. The Scottish Government, their agencies and the LLTNP Board are clearly serving the private interest better than the public interest. The fact that the private interest is almost always not crofters, communities or small landowners, but large estates owned by absentee and anonymous venture capitalists matters not one jot to the people in charge. And as always, the public are footing the bill. Shameful.

Self-seeding Sitka Spruce is widespread at Cashel, not just on the peat bogs, but also in the planted native woodland. Sitka and other devastating eco system engineer INNS need to join Japanese Knotweed in land surveys/homebuyer reports warning prospective purchasers of the dangers, degradation and expense that lie ahead.

The LLTNP has very little money to assist in meeting the zero carbon target at the centre of the Partnership Plan. Once you ignore Visitors and Transport (which in my view was scandalous), then Peat Restoration is the only show in town.

One of the important points Nick is making is that peatland restoration is an expensive option for the tax payer. The most cost-effective and the most efficient toption (based on both costs and benefits) for the tax payer on hill ground is deer control, which can be done at no net cost to the landowner and taxpayer. It generates natural woodland/open ground mosaics, which is so much better for the environment and biodiversity than Sitka or even planted Scots pine.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/13826.pdf

Douglas…. as an academic, can you provide evidence that very low deer densities can be delivered at no net cost to landowners or public purse? At very low densities, you are talking about outings per deer, not deer per outing, and the venison income doesn’t touch that. Community stalking does not work either as those likely to be involved want to see deer to give themselves some encouragement, and you need higher densities to give them the opportunities that they want. In my experience, the net cost of stalking to get very low densities over 10 years or so is very similar to fencing, and will be much more over a 25 year period. You also have the opportunity cost of income foregone. I understand these things can be debated, so I am interested in what evidence you have to back up your comment.

Thanks for your enquiry about evidence Mr Clement. I have carried out extensive independent and objective research on the subject of sporting estate management, having been lead investigator on the largest research projects on deer management ever funded by the UKRCs. I hold a PhD in economics and have a BSc and MSc in Forestry Management. I also stalk deer.

The research results have been published in peer reviewed journals of international standing and involved both questionnaires and in-depth interviews with almost 100 land managers and owners in the sporting estate sector in Scotland. The findings most pertinent to your query on ‘profitability’ are as follows:

1. A significant minority of estates can cull deer profitably because their management objectives include maximising revenue from culling. The majority of estates report losses on culling largely because they prioritise recreational stalking (owner and friends) over paid stalking.

2. For those that increased their cull over the last 10 years, twice as many reported an increase in profits compared to those that reported a profit reduction.

3. There is significant potential for increasing revenues with strong untapped demand from the UK and beyond for deer stalking. These potential stalkers cannot currently access deer stalking because most estates do not market opportunities outside of close friends and business acquaintances.

4. Scottish deer legislation is not fit for purpose and reflects an anachronistic anxiety and concern about ‘poaching’. This legislation hampers profitable deer culling. The anachronistic practices of traditional stalking are not efficient in economic terms.

5. If estates were legally required to cull deer as I have proposed then I would predict this would trigger most estates to modify their management practices and business models to reduce their costs and raise revenues.

6. Venison revenues could also be significantly increased with better marketing, improved efficiency through economies of scale (throughput), and changes in deer legislation.

You can download my papers by visiting my Google Scholar page: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=TYO4pT8AAAAJ&hl=en&authuser=1

Douglas, thank you, I will have a look at that.

Hi Victor, in terms of this debate I think it is important to distinguish between small woodland owners, who by and large are often not rich and currently face significant costs if they want to manage deer without fencing, and the large sporting landowners most of whom are very rich and who, given the will, could like Anders Povlsen and Wildland Ltd, reduce deer numbers. The problem, as Douglas points out, is they don’t want to do so and the financial costs of addressing the problem are then shunted onto others (those costs are not just about protecting trees but road traffic accidents etc)

Nick…. for context, there are about 250,000 deer within the 46 deer management groups which cover most of the Highlands. So, if there are 1 million deer in Scotland overall, then 750,000 are in woodlands and lowland areas where where the average size of landholding is MUCH smaller, and where the vast majority of owners dont do ANY deer control at all, or dont even see the reason why they should. This is also where the vast majority of deer accidents are. Even within the upland deer range, a majority of owners take some income from their deer, and this is an important part of the overall funding equation for employment. I work in the sharp end of this sector, including in areas set up for conservation management, so I understand the dynamics. We should maybe have a chat some time.

If you are working in the deer sector Mr Clements then you must appreciate the fact that the deer population estimates you are quoting are hopelessly inaccurate. Population models (for all deer species) are not up to the task but that does not stop the sporting estate lobby from using them to make claims about red deer populations being under control on the open hill. Never mind the dodgy numbers, look around the hills and all you can see are overgrazed treeless moors.

You have EVIDENCE of more accurate information……. ?

I know these estimates are hopelessly imprecise and undoubtedly misleading. I know this because I understand statistical models and the survey sampling strategy employed. With this knowledge I believe the numbers you are quoting are in no way reliable for policy purposes.

As to actual accurate numbers I have no idea. But my eyes are good and I don’t see any regeneration outwith deer fences or nature reserves, unless there has been a systematic and dramatic increase in culling effort.

Too many who opine on social media about deer numders in the highlands do not actually inhabit areas where deer undermine local farms and add cost to reforesting efforts. The continual reference to some partial surveys conducted occasionally by some deer management groups indicates the deployment of ‘academic’ blinkers. Deer roam about. no one “owns” them . They are a continual problem. A sapling only needs to sustain damage one time for it not to survive.

Last night there were (only) three vagrant deer in the croft fields I can see from this window. Tonight there may be more, or less. Wind direction changes… quite impossible to predict. Low Fences are ignored. The record was 17 one night in the springtime this year. Then a partial cull by the local manager reduced this a bit. But survivors still know where good grass is to be found. Perhaps those who somehow think this mis-use of improved croft pasture land and the neighbouring hill crofting land by ‘freeloaders’ is no real issue, should come and see? Is it better to use HGV to bring vital feed in from hundreds of miles away just to sustain over-wintering livestock? .

Important you raise this issue Tom. The impacts of unsustainably managed deer on crofting grazings, in bye and other farm crops is often forgotten in the debate. On marginal ground where food is scarce for cattle and sheep this impact is serious and deserves more attention from the government – especially one that claims to be putting people first. In times gone bye, I remember going out on the hill at night with a few pals and saying hello to the deer that had taken a liking to the neep patch.