Last Friday the Cashel Forest Trust, set up by the Royal Scottish Forestry Society (RSFS), announced they had put their property at Cashel on the eastern shore of Loch Lomond on the market at offers over £4,085,000 for the whole or as five separate lots.

Goldcrest’s brochure (see here) claims this is an “opportunity to purchase a stunning, wild Estate of international importance”. The facts are the 3069 acre estate is far from wild, having been planted with trees and more recently have had part of its degraded peatland “restored” by diggers. As for its importance, it has not to date been deemed worthy of any of Scotland’s designations designed to protect nature, although it is part of the Loch Lomond National Scenic Area which is internationally important for its landscape.

Cashel Forest is more accurately described as “one of the largest, and oldest, of the ‘new’ native woodlands in Scotland” as the Herald did in an article about the sale last week (see here). This post takes a look at why the Cashel Trust is now trying to dispose of what they once called a Forest for a Thousand Years and the issues this raises.

Background

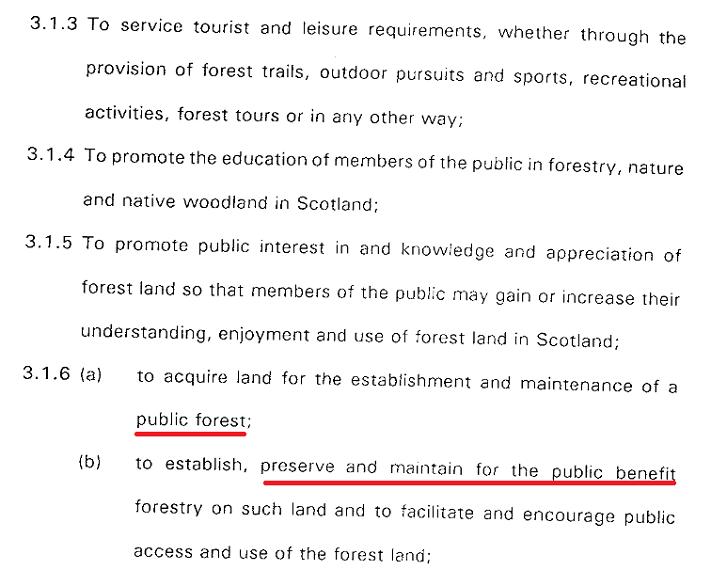

In the 1990s public interest and awareness about Scotland’s native woodland really started to take off. It is within that context that in September 1995 the RSFS set up a charitable Trust Company with a view to buying Cashel Farm, on the east shore of Loch Lomond and turning it into the Forest for a Thousand Years. The original aims of the project, as recorded in the Memorandum and Articles of Association and the accounts of the trust, were far reaching and ambitious:

In short the Cashel Forest project aimed to demonstrate that “good quality timber can be produced” from native woodland which is at the same time managed to benefit the landscape, wildlife, outdoor recreation etc. These aims were to be achieved by planting native trees on Cashel Farm, by converting the farm buildings into a forest study centre and creating a new path network for the public to access the new woodland.

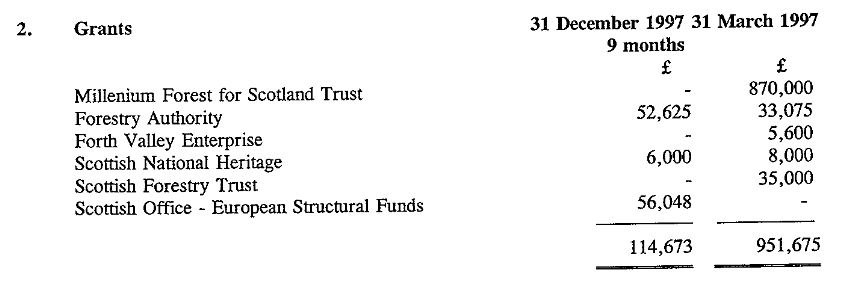

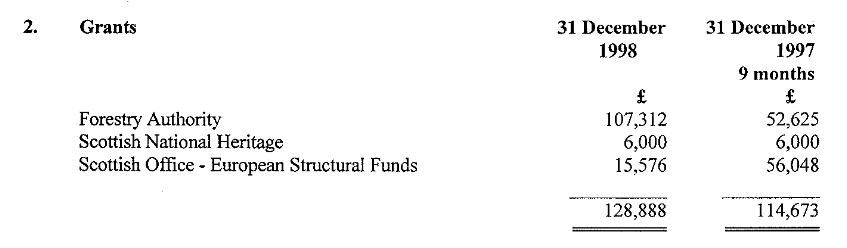

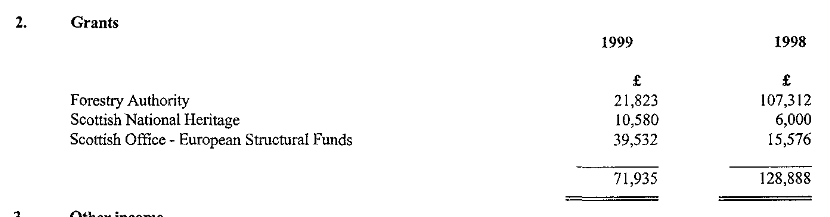

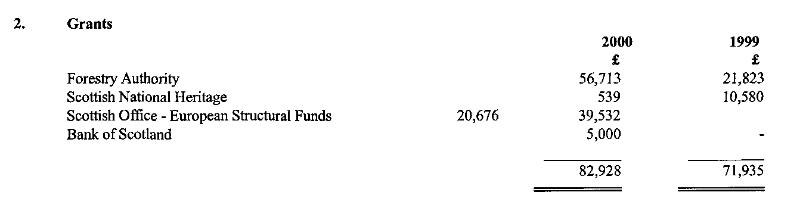

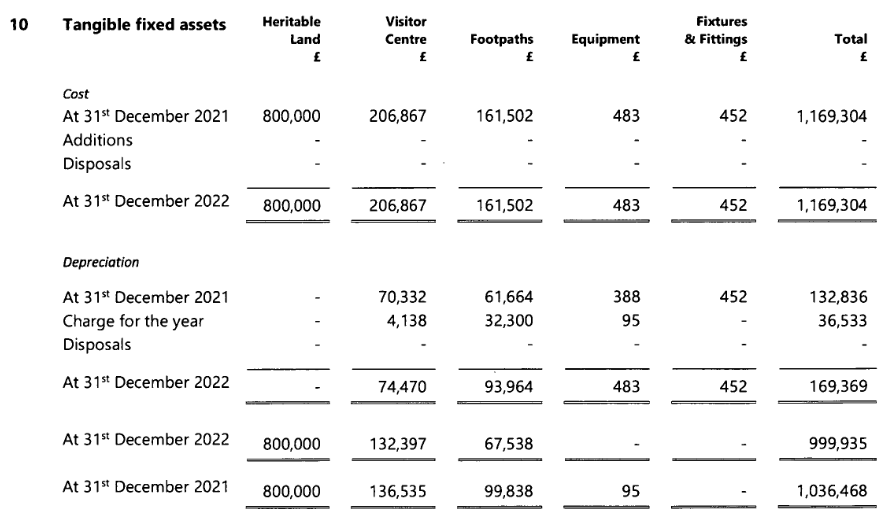

With grant aid from the Millenium Forest for Scotland, a project created with lottery funding to celebrate the new millenium, RSFS bought Cashel farm for £800k in 1996 and proceeded to implement its plans with further grant support, mainly form public bodies. The accounts, available on Companies House (see here), record those early grants:

The accounts also show that after the initial planting, renovation of the farm steading, creation of paths etc were completed around the year 2000, grant income started to reduce considerably. While money was available for capital projects, even then revenue funding was problematic.

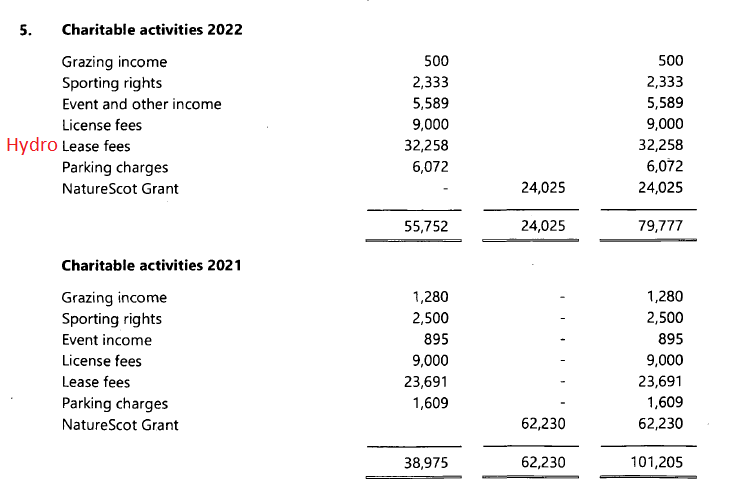

Since the millennium the trust has attempted to create new income streams to fund the management of the project, most notably the hydro scheme but also a host of smaller initiatives from car parking charges to trees planted in memoriam.

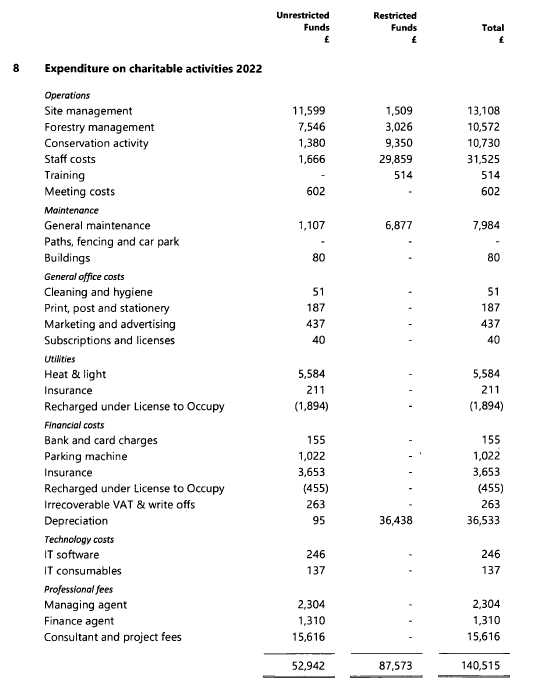

Setting aside the temporary funding from the NatureScot “Better Places” scheme for footpath work and a seasonal ranger, in the years 2021 and 2022 (the last for which accounts have been published) the amount of income available to the Cashel Trust to meet its objectives was extremely limited. That is reflected in the account of expenditure for 2022:

The accounts also reveal that the only person apart from the Ranger who was based on site was the “warden” who received free accommodation in return for limited duties. The Cashel Trust had no money to employ permanent staff, no forester to manage the woodland, no research staff to show what the project was achieving – in short no resource to deliver its original objectives. Almost all the work that was done was undertaken or overseen by volunteers.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that after 20 years of struggling with finances the trustees are exhausted. That would explain the statement in the Herald that “they are looking for a new steward for the land, which they feel they have ‘taken as far as they can’”.

While this account may help readers understand why Cashel has been put up for sale, it does not excuse it.

Public v private interests at Cashel

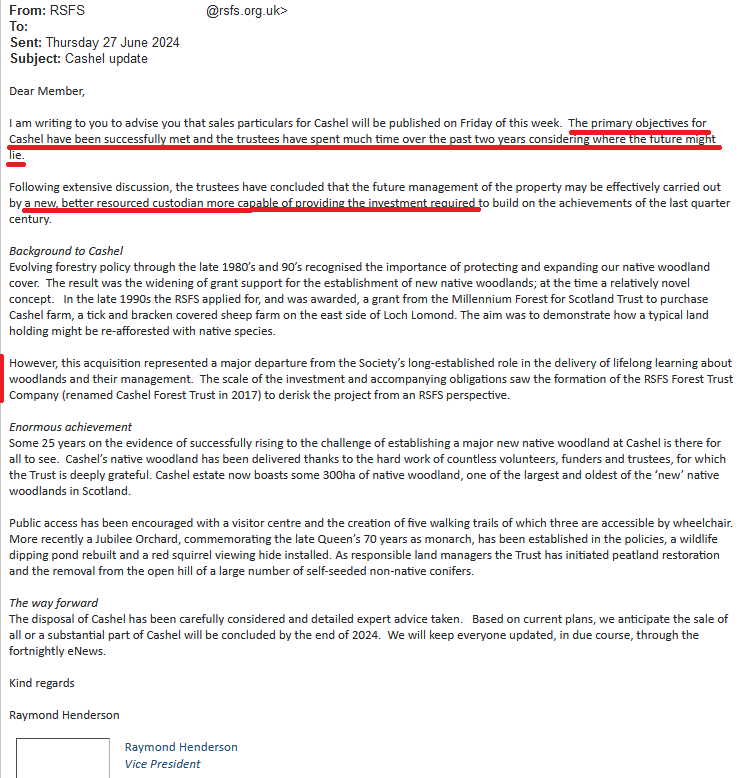

There is no indication in the 2022 accounts that the directors of the Cashel Forest Trust did not view it as a going concern. Moreover, the first that members of the RSFS, the parent body, heard about the sale was by an email the day before the sale was announced publicly:

While the letter correctly identifies the need for investment, the suggestion that the project had been successfully completed is in my view dishonest. Despite all the voluntary effort the Cashel Trust has clearly failed to deliver its original objectives. Rather than consulting ordinary members of the RSFS about this – there has been plenty of time to do in the two years they have spent “much time” considering what to do – it appears the trustees have taken it upon themselves to sell the property. Nor have the trustees or the officers of the RSFS provided any explanation to the membership of what they will do with the £4m if the estate is sold.

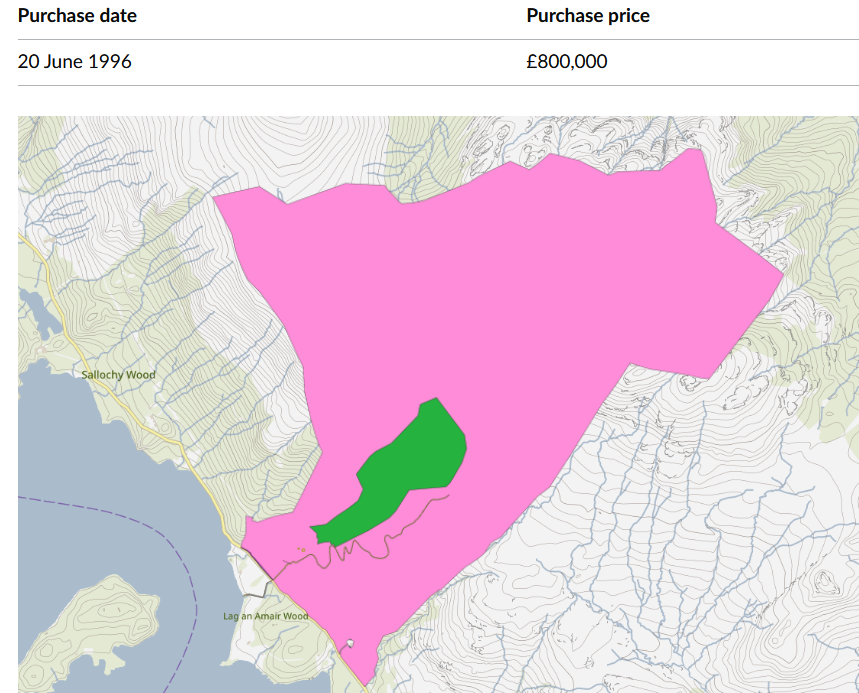

The Cashel Estate was meant to be a public forest and indeed the land was once in public ownership. According to the Registers of Scotland, however, it was sold by the Secretary of State for Scotland in 1983 to the trustees of the firm of J Maxwell. They then in 1984 sold the part of the land along the Cashel burn to Diana Jean Huntingford (in green on the map below). That explains why there is a hole in the middle of the estate and why the Cashel Trust was not able to fully cash in on the hydro scheme when it was constructed 10 years ago. J Maxwell then sold the remainder of the land (in pink) to RSFS:

In short, the RSFS bought back what had been public land with more money from the public, in the form of the funding from the National Lottery. That funding was conditional on RSFS not selling the property for twenty years, a condition which was secured by a standard security which expired in January 2018. That has enabled the trustees to sell the forest without penalty.

In short, the RSFS bought back what had been public land with more money from the public, in the form of the funding from the National Lottery. That funding was conditional on RSFS not selling the property for twenty years, a condition which was secured by a standard security which expired in January 2018. That has enabled the trustees to sell the forest without penalty.

As the extracts from the accounts above demonstrate, the RSFS has received a significant amount of public funding from other sources (along with some other funding from private bodies such as that from the Imperial Society of Knights Bachelor to establish the Jubilee Orchard Gardens to commemorate the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee). Effectively what was supposed to be a public forest at Cashel was rightly bought and developed with public and charitable money but is now up for sale to private interests without any explanation of how the sale proceeds will be used. That is scandalous and threatens to bring the RSFS and its membership into disrepute.

To make matters even worse, the decision to market the estate in lots in order to maximise the potential proceeds is likely to prevent any other public or charitable body buying the land. For example, the farmhouse and steading are likely to be extremely attractive to people seeking a house near the shore of Loch Lomond; if that is sold off separately so will the unfulfilled potential to demonstrate the benefits of native woodland planting and management to the public. Moreover, by marketing the hydro powerhouse separately, the trustees have removed the one reliable source of income that might have been available to new owners of the forest.

The marketing of Lot 3, the 16 acre field at Blair, is revealing: “It is believed that the land might have future potential for change of use subject to gaining the necessary planning approval”. This suggests the trust has had a word with the planners at the LLTNPA who have not said no to another tourist development on the east shore of Loch Lomond. That is likely to preclude the heavily grazed and improved field being turned into a conservation meadow…………….

The scandal, however, goes deeper than this and illustrates the failure of Scottish Government policy when it comes to investing in the land and conservation.

Cashel and the new markets in “natural capital”

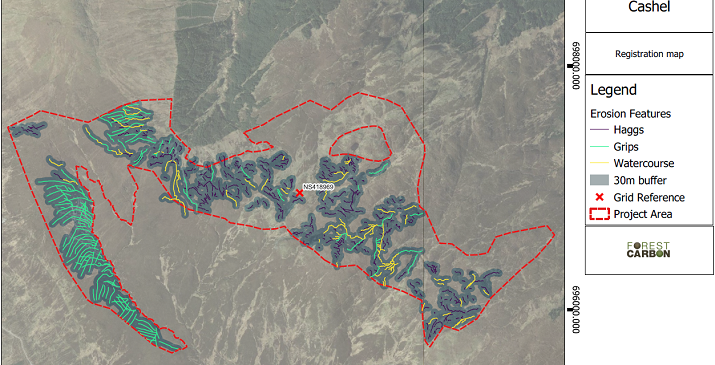

In April the Cashel Trust completed stage 1 of its peatland restoration scheme funded by Peatland Action via the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority. It has registered that land for carbon offsetting purposes under the Peatland Code (see here):

That same land, restored at yet more public expense, comprises the largest part of the estate (2597 acres) and is being marketed under Lot 4, “Beinn Bhreac”, for offers over £2,250,000. The sales brochure states “there is potential for a total of 28,000 Pending Issuance Units (PIUs) which are expected to be issued later in 2024”. (A PIU is effectively a promise to deliver a carbon unit in future based on predicted sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere).

The 349.45 acres of woodland planting in Lot 2, Tom An Eagail Woods, is much smaller and is being marketed for offers over £750k but, unlike many other native woodland planting schemes, has not been registered under the woodland carbon code. I am still trying to understand why not.

Scottish Government policy in relation to mitigating the climate and nature emergencies is now to a great extent focussed on trying to attract private capital to invest in “natural capital” in order to “save the planet” (and humans as a species). The basic idea behind the carbon markets is if a financial value can be attached to woodland and peatland that will bring in a new source of income which in turn will fund conservation management, such as the RSFS wanted to demonstrate at Cashel Forest.

It is remarkable therefore that among the current Directors of the Cashel Trust is Dr Peter Metcalfe Phillips who was appointed in May 2020. Dr Phillips, who is described as a civil servant on the companies house website, is Head of Natural Capital Land Management Policy at the Scottish Government and includes the following statement on Linked In (see here): “

The fact that the current head of Natural Capital Land Management Policy at the Scottish Government appears to have been unable to bring in new income streams for Cashel based on selling carbon credits should tell the public something. The carbon credit system is extremely unlikely ever to produce the income streams that would make conservation management possible. The idea, promulgated by the Scottish Government, that private finance is going to restore nature and climate appears completely and utterly bankrupt. That is not Dr Philips fault, although one might hope he has used his experience at Cashel to urge the Scottish Government to have a rethink.

What has been achieved by the Scottish Government through its support for the carbon credits system is new financial speculation in land, which puts land ownership out of the reach of ordinary people, local communities and the voluntary sector. It is extremely sad that the RSFS, a once venerable voluntary body, is helping fuel that problem and give credence to the whole rotten system by selling off its estate at Cashel Estate without any consultation with local communities or the wider public.

The consequences for the Cashel Estate are fairly predictable, some business is likely to buy up the peatland and woodland areas as a financial investment and all the original idealistic objectives behind the Forest of a Thousand Years will be lost.

What should have happened and needs to happen

It is important to stress that the Cashel Forest Trust has never, after the initial burst of funding, had the money to achieve its objectives at Cashel. That did not mean, however, that the only option open to the trustees was to sell off the land and to try and maximise the proceeds for its own purposes.

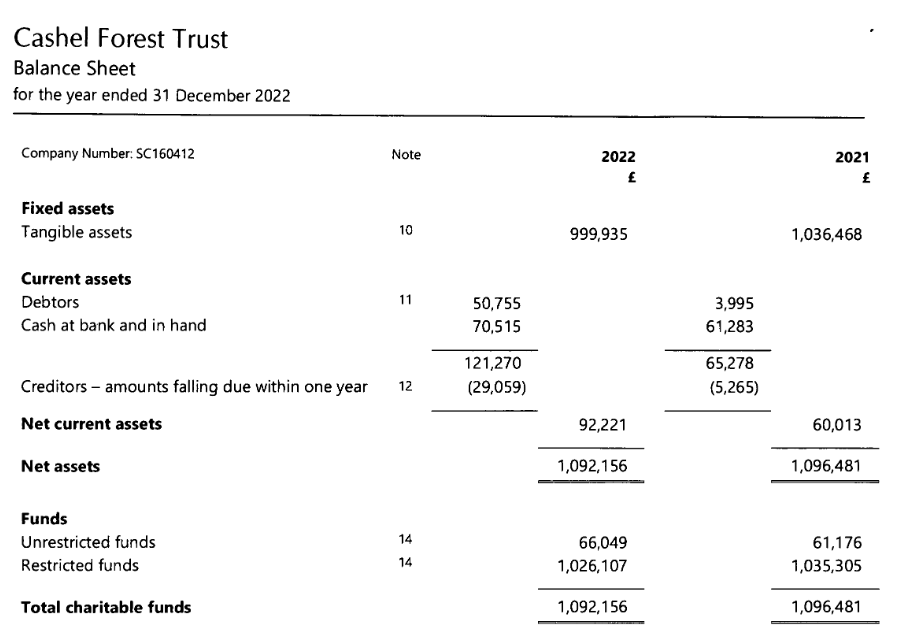

The most recent accounts show that the volunteers for the trust have, despite having very little income, managed its assets reasonably well (even if the buildings are now once again in a dilapidated state):

The main asset is the land, purchased with public grant support, and which has never been revalued so it still shows as £800k in the accounts:

The main asset is the land, purchased with public grant support, and which has never been revalued so it still shows as £800k in the accounts:

The important point to take from this is that the RSFS is not out of pocket and there is no reason why it should not have decided to hand over the land to another public or charitable body who would continue to manage it as a public forest in the public interest.

The trustees could, for example, after consultation have offered to give the land to the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority or hand it back to Scottish Ministers to manage as a demonstration project through Forest and Land Scotland.

The trustees of course may have tried to do this and had their overtures rejected. It appears, for example, that they had close links with the LLTNPA both through the peatland restoration project and because Dr Philips’ linked-in feed includes references to Simon Jones, the LLTNPA’s Director for Conservation. The would appear to know each other. Unfortunately, however, the LLTNPA has never taken any interest in land-ownership or making the case for public financing of conservation management but instead has spent much of the last five years trying to dispose of its own assets to the private sector. In a real National Park there would never have been any need for the RSFS to put Cashel up for sale.

Cashel Forest could still, as one of the oldest new native woodlands, play a really important role in informing future policy and practice about these schemes and be used to drive reform of the Scottish Forestry grants system. What lessons, for example, could be learned from the impact of grazing animals on the peatland, the lack of natural regeneration on site or the poor state of deer fencing (all referred to in the sales particulars etc)? What about the potential to demonstrate and research the impact of tree planting techniques – would Forest Research, for example, not have been better conducting its experiment on alternatives to plastic tree tubes at Cashel rather than in the heart of the Glenmore Forest?

The longer native woodland planting, as financed by the Scottish Forestry grants system and boosted by the Woodland Carbon Code, has continued the more disastrous it has become (BrewDog’s Lost Forest is just one of several examples considered on Parkswatch). Within that context the need for a demonstration project, such as RSFS originally intended at Cashel, is greater than ever. As a voluntary organisation the RSFS could have offered an independent critical view of what is now going on: its claim that its work at Cashel is finished is completely premature and a counsel of despair.

Unfortunately I cannot see the trustees of the Cashel Trust, the senior management and board of the LLTNPA or anyone in the Scottish Government sorting out this scandal. Only public pressure will do so and that probably has to start with members of the RSFS forcing the Cashel Forest Trust to consult publicly and change its decision.

Now, if it was only in a real national park in the first place

So what is happening to the proceeds of any sale? I can see why the Trustees might want to give up if they are finding it hard to get the forest to work as originally hoped, particularly if they are volunteers, but the cash raised should be used for the charitable purpose the Trust was set up for (even if it’s passed on to a different charity with same or similar ideals). Personally as a lot of the original and ongoing funding was from the public purse I think perhaps that should be being repaid if the money isn’t going to be used for the charitable purposes the trust was originally set up for.

Hi Dave, under the terms of the memorandum of association as published on the companies house website if the Trust is the land is sold the proceeds do have to be used for charitable purposes and would go to RSFS in the first instance. If the Trustees of the RSFS have a plan for the money they haven’t told their members.Nick

It’s interesting (?) to see that, according to its website, one of the trustees of RSFS is Fenning Welstead, a founding partner in Goldcrest.

Thank you for doing the work to delve into this mess. Depressing indeed and I hope all who can follow up to express this to the Scottish Government.

Yet again an incredibly detailed investigative post. It is nothing less than shocking that a largely publicly funded area of land is being sold off to the highest bidders – shades of the sale of Scottish Enterprise owned land in Balloch to Flamingoland. In the past I would have recommended that LLTNPA take over the Cashel Estate (not purchase as so much public money has already been invested here). However, even if they did, I am not convinced that LLTNPA would not subsequently go down the same route. Having initially been in favour of National Parks I am now of the opinion that they are just another very expensive, publicly funded tier of bureaucracy. At the end of the day they actually don’t own very much land within their ken, if any. They appear to have very little sway over landowners yet here is a sizeable estate, largely publicly funded, being sold off into private ownership. I seem to remember that in the past Scottish Government stated a desire to buy/take back land from landowners. So why are they not taking steps to do so given the measure of public monies invested here? QED scottish land for Scotland. Also a few years back LLTNPA attempted to engage landowners in a Land Management Plan. That went down like a lead zeppelin (I recall that only 3 landowners within the whole of LLTNPA professed an interest) and has never been mentioned again!

There are certainly questions needing answers here As the article suggests the bigger picture is the government deciding that protecting Nature is best done through treating Nature as an asset that can be bought and sold for big profit on international markets. OUR NATURE is being bought and sold for capitalist gold.

Raymond Henderson who is vice president of the RSFS and leading the sale also makes a living from buying and selling forest land in Scotland.

Having discovered Cashel in the last few years, I am dismayed that it is up for sale and will in whole or part end up in private ownership. A sad fate for this valuable public asset in my view.

Thank you for the informative article and I sincerely hope it can be the catalyst for a solution which preserves the original aims of the trustees for future generations.

Some of the £20 million of public money Scottish Government (SNP) has set aside for Indy Ref 2 would go a long way to bringing this very special, if not unique place, Cashel Estate, into public ownership and maintaining it for years to come. But not into the hands of LLTNPA!

I guess you are trying to score a party political point Mary Jack but that simply is not how government funding operates. It was lottery money that was spent so not strictly government money in the first place. There is a government fund for community land purchase but there has to be a local community that wants to buy it.

“The 349.45 acres of woodland planting in Lot 2, Tom An Eagail Woods, is much smaller and is being marketed for offers over £750k but, unlike many other native woodland planting schemes, has not been registered under the woodland carbon code. I am still trying to understand why not” – for the (bleedin’ obvious) reason that it was planted long before the Woodland Carbon Code was invented…

Nick, thank you for this interesting article, which upsets me deeply.

I have known Cashel Forest for many years, having studied the flora and fauna at this site. It is an excellent example of regenerated, native forest, the type of which should be present all around Loch Lomond, but alas is instead rare and precious.

The regeneration has been successful with high densities of native flora and fauna. To demonstrate and record this, I’ve published a series of papers in The Glasgow Naturalist that describe rich populations of Adders, Slow-worms and Common Lizards and the largest recorded native Crab Apple tree in Scotland and Britain:

https://www.gnhs.org.uk/gn26_1/mcinerny_reptiles.pdf

https://www.glasgownaturalhistory.org.uk/gn27_supp/McInerny_Adders_Conservation.pdf

https://www.glasgownaturalhistory.org.uk/gn27_1/McInerny&Gray_CrabApple.pdf

Other fauna, including moths, butterflies, birds, mammals and bugs (including Glowworms) all thrive at this site.

I had a positive experience with the wardens at Cashel during my work there, and much was done to protect the habitat. But I always assumed that this was a forest “for ever”. No indication was given that the estate could be sold.

As I said this site is one of the richest for flora and fauna in the Loch Lomond area, and is an example of how native habitat can be rescued and improved. That it is in the Loch Lomond NP should give it some protection.

If the estate is sold to private ownership and the regenerated habitat lost through development and public access denied, then this will be a tragedy. The LLTNPA need to consider their position carefully and what their role is in the area.