The 1996 Deer Act created a new duty for NatureScot, the body responsible for the control of deer in Scotland, to take account of “the size and density of the deer population”.

The Report of the Scottish Government’s Deer Working Group, published in 2020 (see here), recommended that NatureScot “should adopt 10 red deer per square kilometre as an upper limit for acceptable densities of red deer over large areas of open range in the Highlands, and review that figure from time to time in the light of developments in public policies, including climate change“. The Report also stated that “many habitats such as native woodlands and peatlands [require] densities well below 10 deer per square kilometre“.

NatureScot, however, still clings to the figure of 10 deer per square kilometre as its benchmark for what is acceptable. On 23rd April it issued a news release (see here) stating its deer reduction targets had been met and claiming that in the area covered by the new Section 7 Caenlochan Agreement deer densities are on track to be reduced to 10 per square kilometre by 2026.

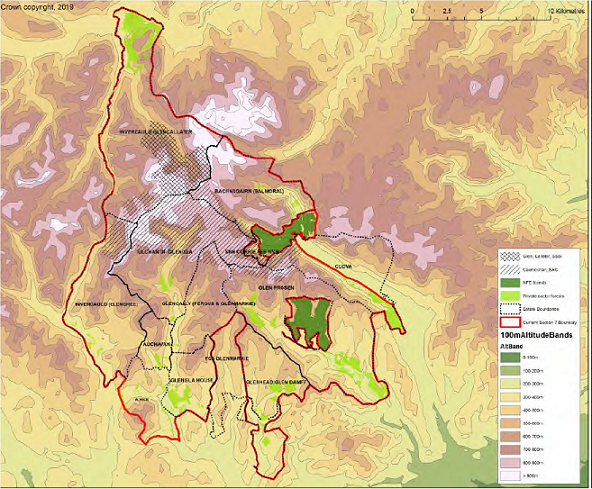

NatureScot first started using its powers under Section 7 of the Deer Act to try and persuade landowners at Caenlochan, who include the Royal Family, to reduce deer numbers at Caenlochan voluntarily 21 years ago in 2003 (see here for the saga). They then let the Section 7 agreement lapse, despite not having achieved it’s objectives, only to renew it after calls from the South Grampian Deer Management Group to do so. They and Tom Turnbull, the Chair of the Association of Deer Management Group (ADMG), are now claiming that attaining what the Deer Working Group stated should be “the upper limit for acceptable densities of red deer” in two years time should be counted as success.

The history of the Caenlochan Section 7 Agreements disproves Tom Turnbull’s claim that “It is clear that voluntary collaborative landscape scale deer management is working”. It was because of their serious concerns about the failures of the Section 7 Agreements at Caenlochan that the Deer Working Group recommended the then Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee of the Scottish Parliament should conduct a short inquiry into what had gone wrong. That inquiry has never happened. It helps explain why the Scottish Government’s current proposals for reforming deer legislation are so weak (see here and here).

Most of the Caenlochan 7 Agreement and South Grampian Deer Management Group areas lie within the Cairngorms National Park. NatureScot’s news release fails to make any mention of the fact that the National Park Authority (CNPA) has adopted a target of 6-8 deer per square kilometre on open hill ground let alone how its own target of 10 per sq km fits with that. Whose side is NatureScot on, nature, other public authorities or sporting estate landowners?

Caenlochan was also once a National Nature Reserve, designated for its rare arctic-alpine plants, until most of these were eaten by red deer. Reducing deer density to 10 won’t reverse that as NatureScot should know from its evidence to the Scottish Parliament in 2016 (see here):

If trees won’t grow until deer density is reduced to 5 per square kilometre – note this is below the CNPA’s lower limit of six deer per square km on the open hill! – there is no hope of more palatable plants doing so.

What is the basis for NatureScot’s density target of 10 deer per square km at Caenlochan?

The figure of 10 deer per square kilometre has been around for a fairly long time but I have been unable to establish where it first originated (help on this would be greatly appreciated!). It was, for example, adopted by the CNPA in their Park Plan for 2017-22 until they reduced it to 6-8 in their latest plan. The Deer Working Group appears to have accepted 10 as the upper limit for deer density on the open hill on the basis that there was very little scientific evidence from NatureScot on which to recommend any other target. NatureScot now claims (see here) that it is usings the figure of 10 per square kilometre because the Deer Working Group recommended it!

There thus appears no general scientific justification for the 10 per km figure (or indeed the CNPA’s 6-8 figure). The most likely explanations for why both have been adopted is that they are acceptable to most stalking estate landowners (particularly when they know NatureScot will undermine the CNPA). Those landowners want to retain high deer numbers partly because the sporting estate market has traditionally valued land by the numbers of stags found on it but also because the owners want to be able to “stalk” deer easily: a contradiction in terms, one might think, but for most stalking estates and their paying clients a day on the hill without a stag in the bag is unthinkable.

If you are to believe NatureScot’s figures (and the Deer Working Group generally didn’t), average deer density on the open hill in Scotland is now conveniently around 10 per square km. That, however, is far far more than was historically the case. NatureScot’s “most recent estimates suggest that there are up to 400,000 red deer on open ground and up to 105,000 in woodlands”. The total is 40% more than were recorded in 1990 and probably over five times the number that existed in the 1950s when the great ecologist Frank Fraser Darling described much of upland Scotland as a devastated landscape.

Much of Caenlochan, moreover, is supposed to be protected as a Site of Scientific Interest, a Special Area of Conservation and a Special Protection Area. The Site Management Statement for the SSSI, which was last reviewed in 2020 (see here), contains no targets for deer density despite the fact the overgrazing and trampling by red deer was the main reason why the site was recorded as being in unfavourable condition. That should be enough to show that NatureScot is totally wrong to apply the 10 deer per square km “upper limit” to Caenlochan.

Last April I walked with a friend along the eastern edge of Glen Isla, from Badundun Hill to Finalty Hill and then back down the glen. That walk illustrated a number of further reasons why NatureScot’s new Section 7 Agreement with landowners to reduce deer to 10 per square km by 2026 is unjustifiable.

The steep and craggy eastern face of Monega Hill comprises about 1 square km. Like the crags around Caenlochan Glen some of it is inaccessible and it is clearly incapable of supporting an average of 10 red deer for a year. This means that actual deer density in the areas available for browsing within the Section 7 Agreement area will still be significantly higher than 10 per square km if and when NatureScot’s targets are met.

The short growing season coupled with snow lie means there is very little food for deer for much of the year on the high plateau, which comprises the core of NatureScot’s Section 7 Agreement area. This serves to increase the average annual number of deer on the lower and more accessible still further. But when the deer do visit the higher ground over the summer and autumn months there are too many for the degraded vegetation to bear:

NatureScot’s deer density target for Caenlochan also appears to have completely ignored the need to consider the impact of deer not in isolation but alongside the impact of other forms of land-use, including other sporting uses that damage the natural environment:

While muirburn removes older heather and promotes new more palatable growth, together with overgrazing it reduces plant diversity while increasing soil erosion and water run-off.

What needs to happen

The case for a Committee of the Scottish Parliament to hold a short inquiry into NatureScot’s use of Section 7 agreements at Caenlochan is now even stronger than when the Report of the Deer Working Group recommended it in 2020. The Scottish Government’s response to that recommendation was it was up to the Scottish Parliament to do so. With the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee having been abolished, the recommendation appears to have become lost. It should now picked up by the Rural Affairs and Islands Committee, who are now responsible for land-use, before the Scottish Government introduces any of its proposed amendments to deer legislation.

But what the Rural Affairs and Islands Committee could now also usefully do is to extend the inquiry so it also covers just how NatureScot became so wedded to a target deer density of 10 per square km.

The rest of this mini-series of posts will pick up on the Deer Working Group’s recommendation (paragraph 52) that:

“the Cairngorms National Park Authority and Scottish Natural Heritage should have a much greater focus on the need to improve the management of wild deer in the Cairngorms National Park, to reduce deer densities in many parts of the Park to protect and enhance the Park’s biodiversity”.

The posts will take a further look at the 10 per square km deer shibboleth, which has implications for the whole of Scotland, and how this is preventing nature from restoring itself through natural regeneration. I will use examples from around Braemar and Balmoral, where I was last weekend, to show what happens when deer densities are reduced to 2 per sq km or less and what happens when they are not.

NatureScot (today’s brand name for the legal entity Scottish Natural Heritage) cannot escape from the evidence that SNH gave to the Scottish Parliament in 2016, that “a density of 4 to 5 deer per km2…. is the sort of deer density to look for if you want to establish trees without fencing” (see above). In other words, the current promotion by NS of 10 deer per km2 is bound to fail in efforts to promote the restoration of montane and woodland habitats. The 10 deer per km2 figure is based on landowner pressure, not science, as they strive to maintain the status quo, with large herds suppressing natural regeneration for sporting, not biodiversity or climate change objectives. The role of Balmoral Estate in this “business as usual” attitude is crucial, as the Royal Family not only owns part of the montane habitats of Caenlochan, but also the majority of the Ballochbuie ancient Caledonian Pine Forest to the north, all lying within the South Grampian Deer Management Group. King Charles needs to get a grip of this situation. He cannot continue to support deer population densities which are double the scientific recommendations made 8 years ago in an area which was identified by the Scottish Government’s Deer Working Group, 5 years ago, as the worst area in Scotland for the repeated failure of voluntary deer control schemes over a 20 year period.

The same publication and these August bodies complain when groups attempting to plant trees use fences. My answer to all these gum slappers is the same. Get out there and plant trees and get utterly ruthless at culling deer. Furthermore, if biodiversity is to increase on the these landscapes then plant beaver as well.

Is biodiversity the goal or are the trees a cash crop?

We will lose biodiversity with beavers.

Reading the article and the two replies posted so far it sounds to me as if you want rid of the deer across the hill/ moorland areas of Scotland completely.. I walk in the hills frequently both on mainland Scotland and on the Islands in the west and the number of deer I come across has been severely depleted due to Government policy over recent years. The picture posted showing 18 hinds on a huge mountain range is testament to hatred for the red deer. 18 is not a herd it is a family group. It amazes me the way the red deer in particular is blamed for climate change etc. A very biased article I’m afraid.

Gordon, your experience appears to contradict the facts https://www.nature.scot/sites/default/files/2019-11/A3115490.pdf. Average deer numbers across Scotland have dropped but only slightly since 2000 but that can be accounted for by the reduction of deer by conservation owners (Cairngorms Connect, part of Mar Lodge, Rauslings) and grouse moor owners – there are NIL deer at Delnadamph, King Charles’ estate.

Gordon when I lived in the edge of Perth I often saw 5 or more deer on my walk to the supermarket. But this means nothing at all when the subject is deer numbers in Scotland. It’s just what an old man saw on the way to Tesco.

Your own observations have a similar status.

It is nothing to do with wanting rid of deer. It is simply that deer are stopping vegetation growing. That vegetation enables the ecosystem to develop and support many other creatures as well as deer. So the presence of large numbers of deer are maintaining a stunted supressed ecosystem. Without apex predators the ecosystem is completely out of kilter. It is virtually an ecological desert. It doesn’t even suit the deer. They are healthier and grow larger where numbers are fewer and there is more woodland. After a couple of decades of very low deer numbers the ecology will be recovering and likely deer numbers could be allowed to increase. There will then be many other creatures to see on the hills not just the odd deer. At Mar lodge it took deer numbers below 3 per square km for the pine woods to start to regenerate. With this regeneration comes the increase and return of many other species alongside deer.

Hello, You asked for the source of the 10 deer per km2 figure. I think it is this publication:

https://www.fas.scot/downloads/tn686-conservation-grazing-semi-natural-habitats/

It states:

Where red deer are the primary grazing animal in upland areas, grazing levels are generally expressed as deer per km2 and are typically low if converted into LU/ha. This is partly due to the fact that large upland areas include significant areas of fragile and low-quality grazing such as blanket bog and alpine vegetation above the tree-line, and partly due to the habit of deer of concentrating in favoured areas (particularly in winter) and their greater propensity for browsing of heather and other shrubs, compared with sheep. Anything greater than 20 red deer/km 2 (equivalent to approximately 0.06 LU/ha) would normally be considered a very high density with potential for negative impacts on vegetation. Around 5-10 deer/km 2 is likely to result in low to moderate impacts across most large upland areas, but some areas may sustainably support higher densities than this. In recent years there is an increasing emphasis on using vegetation

monitoring as well as considering deer densities to manage upland deer populations

As you’ll see it actually advocates 5 to 10, not 10. However, there is no evidence presented as the basis for either figure.

On densities, agricultural support schemes require a MINIMUM of 0.05 LU [ed “livestock units] per ha, which is higher than almost all deer densities in Scotland. 10 deer per sq km is 0.03 LU per ha. So, to make sense of deer/ herbivore densities, and whether they make sense or not, I would suggest we look to deal with the mixed messaging first.

The text above says 5-10, and sometimes higher might be sustainable. The average deer density in the Highlands is 8, so within the range suggested, and well below the MINIMUM figure given where sheep are grazing.

You are right about the mixed messaging but do you think that these benchmarks for levels of livestock grazing reasonable? I am approaching this from another direction, work out what deer densities (without sheep)are compatible with natural regeneration of woodland and from there we can work out the implications for sheep, cattle etc.

The messaging re woodland regeneration or no are even worse….. !!