I am very grateful to all the people who have promoted my post on Sunday (see here) about Scottish Forestry and the tree planting disaster at Kinrara and my apologies that the parkswatch website then crashed. This does not appear to have been due to a cyber attack by defenders of the forestry grants system or even the volume of people trying to access the post but rather a botched attempt by myself to change my wordpress theme and make the typeface darker and easier to read (still not sorted, I have had to manually change the typeface in every para of this post)! Anyway, because of the website crash many people who came to parkswatch for the first time may not have appreciated that I have been documenting what has been going at Kinrara ever since BrewDog bought the estate three years ago (see here). Now seems an good opportunity therefore to add to that record by explaining how BrewDog’s planting and the forestry grants scheme has impacted on the experience of visitors and locals alike.

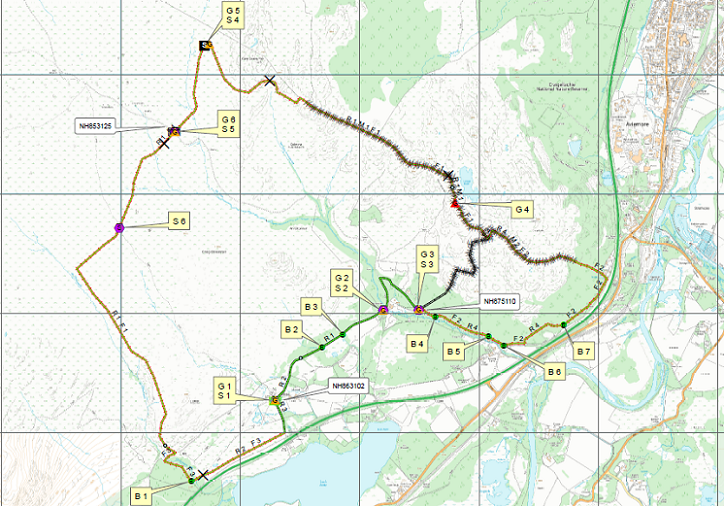

The impact of BrewDog’s new deer fencing on access

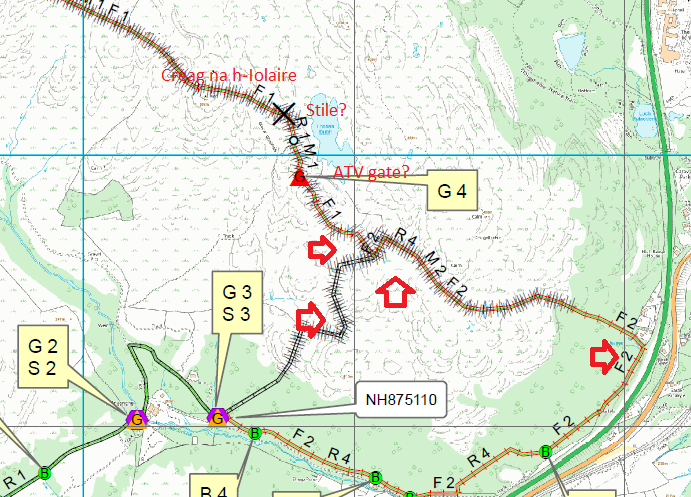

After writing in January about the stupidity of erecting new deer fencing which the evidence shows will kill the endangered capercaillie (see here) , I was sent the photo along with this commentary of what happened after they had walked up the Burma Road and returned via Creag n h-Iolaire, a route they had walked before with no issues:

“This time and quite unexpectedly on my way down, I became corralled by the new and very high deer fence(s). I know there is a lot of new fencing but what I didn’t expect and was unable to see due to the terrain was that the fence(s) crossed my path, running off in various directions and literally fenced me in. I searched through my binoculars for signs of styles along the fencing that I could have used but could see none.

The lost landscape at Kinrara

Anyone who has explored the land along the western edge of the Cairngorms National Park between Kingussie and Carrbridge will have across areas of beautiful native woodland on the flanks of the Monadhliath below the generally overgrazed and burnt moorland above. The survival of this woodland is partially explained by the sporting estates which own this land (eg Balavil and Dunachton) valuing it for pheasant shooting – other woodlands remnants have survived in gorges and similarly inaccessible places.

Many of these estates then took advantage of the introduction of native woodland grants funding to extend this woodland – effectively a public subsidy for game shooting – but this was generally for relatively small areas of ground. This was basically the position at Kinrara before the owners decided to sell the land to a new laird.

Before BrewDog bought Kinrara in 2021 the estate had ceased to manage the land for shooting game birds and the woodland remnants had started to regenerate naturally. Had that process been allowed to continue the landscape would have changed gradually in a way that would have enhanced the natural beauty that had survived the muirburn. BrewDog, however, wanted to be seen to be doing something. With Scottish Forestry offering to get the public to foot the bill, planting trees over as much of the area as possible became a financial no-brainer.

The consequence for the landscape have been far reaching.

BrewDog may have planted native trees instead of non-native conifers but their new plantation looks and is going to look just as bad as the notorious sitka plantations of the 1970s, piles of exposed peaty soil and serried ranks of trees. While the public subsidy framework for forestry (tax system and grants) now pays to plant native trees as well as conifers, little else has changed: planting is still based on an industrial model that favours trees being grown as densely as possible. Hence the pockmarks picked out by the snow.

While much of the surface unsightliness will in time be hidden by trees, those that are planted and survive will still form even aged blocks, completely different in appearance to natural woodland.

The importance of green space for mental and physical health is widely acknowledged in Scotland but the implications of that for Scotland’s forestry system have so far been ignored. Kinrara was far from perfect – managed for sporting purposes, much of its hillsides were scarred with muirburn and, over the watershed in the Dulnain, overgrazed – but the creation of the Lost Forest has destroyed much of the natural beauty that did exist.

Responsibility for the adverse impacts of large scale tree planting on the landscape, which also destroys peaty soils, releases carbon into the atmosphere etc, lies as much with Scottish Forestry, which oversees and directs the whole system, as individual players like BrewDog. But it takes two to greenwash.

Caring for the landscape – a recreational perspective on infrastructure

The Burma Road was upgraded prior to being sold to BrewDog and the creation of the ugly borrow pits along it was the responsibility of the previous owners. While the Cairngorms National Park Authority could have used its planning powers to require the sides of these pits to be landscaped and the vegetation restored it has never done so.

Having bought Kinrara, BrewDog could have decided to restore the damage done to the landscape by others, as Wildland Ltd has been doing in Glen Feshie and Glen Tromie. So far there has been no indication that they have considered doing this, although as part of the their grant contract with Scottish Forestry they did agree to remove old deer fencing.

Sometimes, relatively small things can tell us a lot about a person or organisation’s attitude to the landscape or countryside – like an empty can left at a summit cairn. The bridge in the photo above was damaged by one or more the heavy vehicles being driven up the Burma Rd as part of the Lost Forest Project, whether to “restore” the landscape by planting trees or “repairing” damaged peat bogs. If my memory is right this was brought to BrewDog’s attention and they said the problem would be fixed. Whatever the truth of that, aAlmost year later the damage had not been repaired :

As for the landscape impact of deer fences……….I don’t think I need to publish any more photos of the fences around the Lost Forest to show their landscape impact. I will, however, tempt fate and declare I have never come across anyone who thinks they enhance to landscape. (BrewDog’s contract with Scottish Forestry says they will remove the fences at some undefined point in the future when they are no longer needed).

Re-wilding – the importance of the recreational perspective

While much of current debate about rewilding is framed in terms of how best to restore damage to nature, the first people to really value wild land, such as John Muir to Percy Unna (see here), did so from a recreational perspective which valued landscapes which looked and felt wild. That attitude, of valuing wildness, is now held a very large proportion of the population in Scotland. A YouGov poll for the John Muir Trust in 2017, for example, found a large proportion of the population in Scotland wanted wild land areas to be protected while a more recent survey focussed on the wild places people value close to home.

In respect of Kinrara, it is noteworthy that the people who have alerted me to much of what has been going on and sent the photos credited to “parkswatch reader”, in this and other posts, have not been visiting mountaineers but local residents who value the area for “recreation”. The view that is still promulgated by some that “wild land” is incompatible with the needs of local communities in the Highlands appears to me fundamentally wrong. It is, for example, the local community that has been leading the objections to the telecommunications mast in the heart of Torridon (see here): there is no contradiction between wanting 4G telecommunications where you live and a wild place out the back where you can get away from it all for recreation.

From a recreational perspective there is a massive difference between the current Scottish Government financed schemes to restore nature through large-scale interventions in the landscape and doing so through re-wilding or enabling nature to restore itself. In the case of woodland restoration the difference is between planting and natural regeneration. The two approaches affect the landscape in very different ways. This is well evidenced by BrewDog’s planting of its Lost Forest, which is best described as brutal, a complete contrast to the much “gentler” processes involved in the natural regeneration which is evident across the site.

In the posts that preceded this, I have shown how not only will the Lost Forest be leaking carbon into the atmosphere for years, due to the destruction of peaty soils, but how most of the trees have died. The planting has been both an disaster for nature in the area and for the humans who used to enjoy it. The Lost Forest is not an isolated case: “if it looks bad, it almost certainly is bad”. What the recreational perspective should tell the Scottish Government is that these large-scale planting projects are not a means of speeding up the restoration of nature or a means of giving re-wilding a kick-start, as often claimed, but a destructive intervention in the landscape.

Were the Scottish Government to adopt a “holistic” approach to nature and people, they would promote an approach to land-use that embraced nature restoration, carbon offsetting, outdoor recreation and landscape. This would include a new approach to forestry where subsidies for planting trees were abolished and instead financial support provided to enable both native and “commercial” woodland to regenerate naturally by reducing deer numbers as happens across most of Europe. This would be a far cheaper and more effective way of addressing the climate and nature emergencies in upland areas than destructive projects like the Lost Forest.

This is not to argue that ALL tree planting is bad, either ecologically or from a recreational perspective. Indeed, volunteers going out to plant a few trees by hand rather than by digger is for many people a valuable recreational experience. We need to be careful, however, that such planting is not used to legitimise practices which damage the natural environment, including planting on peaty soils (of whatever depth), the use of plastic tree tubes or the application of herbicides. The starting point for native woodland restoration, if we really want to achieve the oft quoted policy objective of “the right tree in the right place”, should be to leave most of the choices to nature.

Well said Nick, and thanks for making the pages more readable. I too, as an official owld git, was having difficulty with the old grey print style.

Plus one, new text is so much easier to read thanks.

I was up the Corbett last week and the damaged bridge section has still not been repaired

Well done for drawing attention to this government subsidised vandalism.

Sincerely,

Alan Brown

A local resident

Another great post, Nick, but I must take issue with the statement: “The importance of green space for mental and physical health is widely acknowledged in Scotland”. The Scottish Government – if you’re referring to our current batch of political leaders – loves a soundbite, doesn’t it. They might understand and relate to a city park, perhaps even a country park, but they don’t respond well to untamed nature and true wildness. With every new and superfluous windfarm concreted into our peatlands, with every new monster track bulldozed across a previously unspoiled landscape, and with every gratuitous weir choking a dying burn or river, including in the high corries of our finest mountain ranges, a little bit more of my personal mental health sickens and dies. Put real lovers of nature in the place of soundbite politicians and Scotland might just get what it needs.

Great comment. These people are vandals.

Great swathes of Scotlands wild places are being destroyed.

Back in the day, when there were real foresters on the ground ..who knew the ground and cared about sustainable Forestry, this situation would never have happened. This fiasco is the trademark of consultants…paid big money by corporate investors who don’t care about the land…only their bank sheet. A proper forester would have seen the natural regeneration and planned accordingly but Brewdog would have sacked him because going with natural regeneration would have cost them big money…in carbon credits that is. What we are seeing is corporate business treating land as a financial asset. Scottish Forestry is working hard to facilitate this model by turning a blind eye to Environmental destruction and using carbon credits as a convenient scape goat/ smokescreen

Back in the day they were draining peat ground to plant trees at 1.8m . Only green spaces left were fire breaks and they just help planters to get trees out. And I’d also like to see you flat plant trees in rank Heather . Few hundred thousand trees flat planted in to veg taller then the trees never work… the price the contractor was paying his planters on this site would sucre the fact that boys are taken trees off site and saying they planted them. The rates for tree haven’t went up in 50 years but have went down dramatically in price mostly due to foreign planters coming over with no work visa and being happy with the peanuts there paid before returning home without paying taxs

I should add that mortality in planted stock is normally 5-15% . The very high mortality rates here suggests it is time to re-think the use of mounding to plant trees. The peaty mounds quickly dried out in the drought which took place soon after the trees had been planted last year starving them of water. With global warming such conditions are becoming more likely. The Natural regeneration indicates trees can grow here. But naturally seeded trees will prosper in places nursery stock will die, for example because the lack of soil and vegetation disturbance around them means the ground retains its moisture far longer in drought conditions.

Yes and whoever advised on that planting method should bear the cost of failure.

“You cannae go up there sonny, it’s set aside for stalking/sheep/grouse”

“You cannae go up there auld man, it’s set aside for Re-wilding”

(Still an effing dessert though)

Great article Nick. I fully endorse your points about a holistic approach and the awful results of industrial greenwashing. Almost everyone who loves the Highlands knows what “natural” looks and feels like and plantations rarely get even close to that.

On the point of access, is there any scope for guerilla gate installation on the estate?

Thanks Stuart, I have now come to the belief that the only way to address some of these issues is direct action but the powers that be will condemn this as irresponsible. I will therefore now submit a complaint to the Cairngorms National Park Authority as access authority and ask them to address the access obstructions caused by the fence and require BrewDog to put in stiles every 500m. They could of course have required this when commenting on the grant application but as far as I know never did so. Will do a post on how this goes in due course. In the meantime I would not criticise anyone who was forced to bend back the chicken wire netting on the lower half of the fence as the only way of getting a foothold to climb the fence

I stupidly In hindsight bought into the brewdog forest scheme by choosing to buy brewdog forest beer in 2022 over others, at a small personal amount because they talked a good game and stupidly, I thought, they are Scottish, they aren’t foreign corporate.

Having followed this disaster, albeit not commercially for brewdog, I have now avoided any of their products and endorse others/friends to also do so. They could have done so much yet outsourced it to accountants and poisoned any well doing.

Shame.

It could have been a good thing, they screwed the pooch.

“outsourced it to accountants”

Who have they Outsourced it to Duncan?

I can’t find any information on this.

Can you tag a source?

Thanks

Just after visiting Loch Tummel and after doing the tours to Braemar and Blairatholl I couldn’t help being surprised at the amount of tree cutting in the area. Areas of natural beauty interspersed with areas of tree stubs. We also couldn’t help noticing the devastation around the Loch Tummel area itself with plants and buildings entirely devoted to generating electricity, probably destined for down south. Perhaps our gov could investigate these grouse moors and hunting because they add nothing to these areas except misery for the animals. Hugh Josey

Boycott Brew Dog.

“Boycott Brew Dog.”

What do you think happens to the land if Brewdog fails as a business, Stephen ?

Let me help you out, the land goes to the Bank, and gets auctioned to the highest bidder.

With luck Andres could buy it up, but he had the opportunity to do so previously and didn’t.

A cash rich fund that has been buying up land in Scotland could buy it, and I don’t see that having a positive outcome, seeing what they are doing elsewhere.

You and the “direct action”, promotors above might be better adding your voices to those who engage with Brewdog seeking to challenge and influence constructively.

Buy a share, currently around £6.50, for a 5% discount on Bar and online purchases, or buy 20 to qualify for 10% discount.

This would then give you an invite to the Agm, a chance to ask questions and challenge directly.

Thanks for the great article.