Deer fencing and stock fencing generally serve very different purposes, the former is used to keep deer out, the latter to keep sheep and cattle in. While I have covered the disastrous consequences of deer fencing quite often on parkswatch, most recently in relation to the case of BrewDog’s Lost Forest and its impact on wildlife (see here), I have hardly discussed the impact of stock fencing. This post will argue that, while not without its issues, it is generally far more beneficial.

A visit to Glen Feshie at New Year to take a look at the damage caused by Storm Gerrit provided a good illustration of the positive role that stock fencing plays in protecting the wider natural environment.

Spruce are fairly unpalatable to grazing animals but in hard times, like the middle of winter, provide a welcome additional food source. When the grass is grazed almost to its roots, sheep turn to other fodder. This also accounts for why the strip of woodland behind the field has no understorey and explains the height of the lowest branches – anything within reach of hungry mouths gets eaten.

For the same reason, leaving sheep on the open hill in winter, at whatever density, is generally disastrous for woodland expansion and development: any tree that pops up above the snow has little chance of survival.

Woodland, such as that on the edge of this exposed field, plays an important role in providing shelter to animals in bad weather. Unless, however, access to woodland for this purpose is strictly limited in extent sheep and cattle will kill off the understorey and prevent natural regeneration just as surely as deer. Stock fences therefore currently have an important role to play in managing this and, if the enclosures the include woodland are moved over time, can enable the grazed areas to recover.

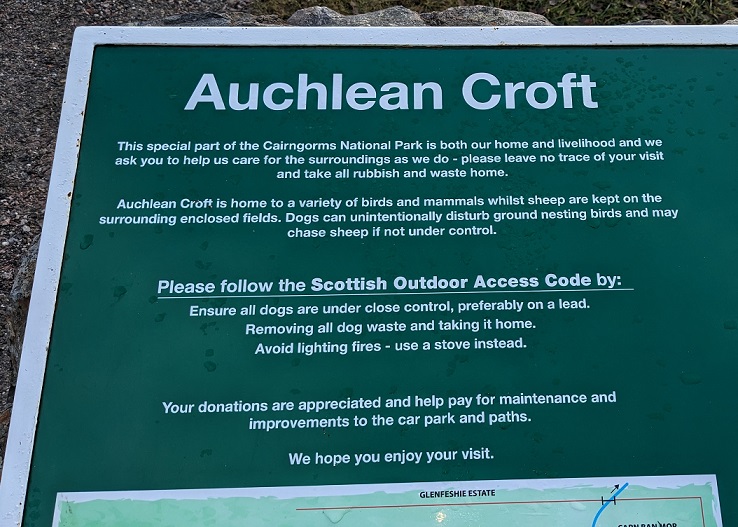

What this sign says about how crofting is is practised in Glen Feshie is very important: “home to a variety of rids and mammals whilst sheep are kept on the surrounding enclosed fields”. The starting point for land-management here is that livestock grazing should be controlled and takes place on enclosed land.

There are issues with stock fencing as a means of controlling grazing and in future it may become redundant. Sheep are surprisingly nimble animals and unless the fencing is well-designed and well-maintained will escape their fields. The barbed wire that is often found running along the top of stock fences prevents access o humans and can seriously harm animals: in 2009 Norway banned the use of new barbed wire fencing for animal welfare reasons (there is lots still left).

Stock fences also form barriers to wildlife, particularly when covered in wire mesh, and will like deer fences kill some birds – their impact on threatened species like capercaillie is something that deserves research. All these issues, however, could now potentially be solved through no fence technology (see here) which is now being used to control where cattle graze, sometimes as at Abernethy in woodland for conservation purposes.

Sooner or later no fence technology is likely to become a cheaper financial option than stock fencing for sheep too, enabling any grazing on the open hill in the summer months to be strictly controlled too. No fence technology has the potential to offer other benefits too: for example, to plant hedges round fields for conservation purposes without the need for any wire fencing to protect them from the animals inside.

There are questions about the intensity of grazing on enclosed fields which deserve further thought. If the sheep in the field shown are hungry enough to eat unpalatable spruce, perhaps there are too many? This is not the fault of the farmer, who has to make a living in very challenging circumstances, but of the rural payments system which is not properly designed to support wildlife friendly livestock grazing that promotes animal welfare.

The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) could be working with local farmers and crofters to trial new methods of controlling livestock and to work out sustainable levels of grazing. Potentially this could be a win-win for farming and wildlife building on the experience of the lower reaches of Glen Feshie and similar such areas.The CNPA added an action (A8) about promoting more sustainable farming to its National Park Partnership Plan which included the following indicator: “Target rural payments to support sustainable food production, reduce carbon, increase and maintain the health of habitats and ecosystems, enhance biodiversity and help connect different habitats across the National Park”. Working with the farmers and crofters who do the right thing by keeping their livestock on enclosed ground would be a good place to start.

Meantime the public through the Scottish Government should be subsidising stock fencing, not deer fencing and paying farmers enough so they can keep it in good condition. The farmers affected by Storm Gethin deserve to get compensation for all those stock fences damaged by falling trees.

Ever thought what happens when it snows?

Something that happens occasionally in the CNP.

Anything from deer,rabbits and jings even sheep will eat greenery even when other feedstuffs are available.

As an aside the used to mill gorse to feed cattle.

Barbed wire should be banned in Scotland, as in Norway. You virtually never see barbed wire today in Norway and that restriction appears to cause no difficultly for farmers. Modern stock fencing, with firm posts plus a top wire under tension is sufficient, or the use of the “no fence” solution with sheep and cattle controlled by a GPS collar system and monitored from the farmhouse. This no fence system would be ideal in Scotland for keeping sheep and cattle out of rocky places, burns and river banks, to enable habitat recovery and the expansion of the trees and shrubs usually found in such places.

I agree about Nofence but the collars are £240 + VAT and a £900 subscription for 20 cattle. That’s only economic with a subsidy. Roy Dennis has written about the importance of cattle grazing the forest for Capercaillie habitat: he recommends that 500 cattle should graze Abernethy forest. £120,000 for the collars without the annual subscription. Would RSPB members pay this?

In all the years I have followed parkswatchscotland I don’t think I have ever seen a positive post from yourself. I think you could rename it moanscotland.

The way the countryside is being abused it’s not surprising you haven’t seen a positive post.

Someone who thinks the status quo is fine, maybe has a vested interest in the abuse continuing.