Following my post on deer fencing and capercaillie on Speyside (see here), a friend and sometime contributor to Parkswatch, Nick Halls, brought to my attention to the latest issue of the Geographer, the magazine of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. It is all about trees. In it there is an interview with Thomas MacDonell who has been responsible for managing the Glenfeshie Estate for the last twenty years. Asked about capercaillie, he responded there none when he arrived but this year there were 13 cocks at the lek. Besides reducing deer numbers to less than 2 per km and improving habitats as a consequence, Wildland Ltd has systematically been removing deer fences from Glen Feshie and its other properties.

As a result of research into the impact deer fences on black grouse and capercaillie in the 1990s, twenty years ago the Minister at the Rural and Environmental Development, Rona Brankin, allocated £700,000 of government funds to remove and mark fences. This resulted in the removal of 87 km and the marking of a further 134 km of deer fencing during the year 2001-02 in areas where capercaillie lived This was a big step in the right direction. Since then the emphasis has changed from removing fences to marking some of them – with some exceptions like Wildland Ltd – and there have been no further surveys to measure the effect of fences on woodland birds or any other species.

With the capercaillie population about a half to a quarter of what it was 20 years ago, if the Cairngorms National Park was even half serious about saving the capercaillie, it would ensure all other landowners on Speyside followed the example of the RSPB at Abernethy, who had taken down their fencing 20 years ago, and Wildland Ltd. Instead, it has stood by and allowed Scottish Forestry to fund BrewDog to erect over 10km of new deer fencing at Kinrara which borders some of the last remaining places capercaillie are found.

BrewDog’s killer fences

It has been known for over 20 years that deer fences (1.8 m high) have been killing ALL woodland birds. The effect is most serious for capercaillie and black grouse. An experiment (see Abernethy Forest by Ron Summers page 296) showed that marking fences with orange plastic netting, as subsequently was done at Kinveachy (see here), reduced fatal collisions by 64% (95% confidence limits 8-86%) for capercaillie, and by 91% (95% confidence limits 67-98%) for black grouse. The wide range of the confidence limits for capercaillie shows the level of uncertainty. Marking helps but it does not stop these and other birds being killed in collisions.

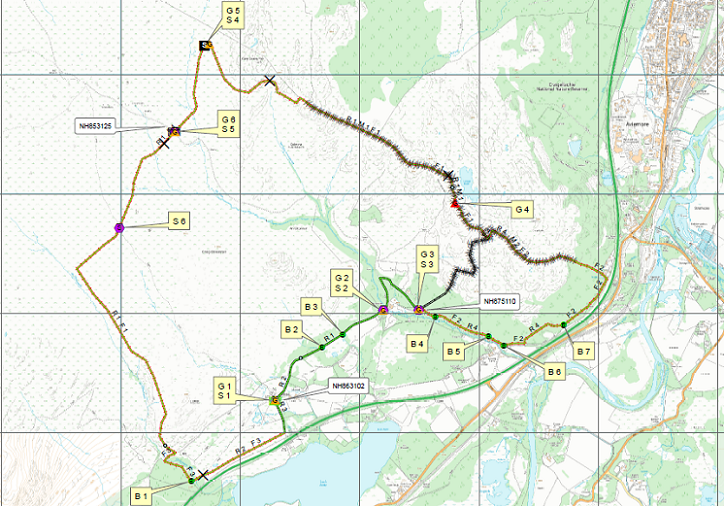

This map helps show the proximity of BrewDog’s lost forest to Aviemore and some of the main centres of the remaining capercaillie population on Speyside. Craigellachie National Nature Reserve and Kinveachy, where good work was done with the mountain biking community to reduce their potential impacts on capercaillie, border the north east facing section of fence. The Glenmore Forest starts just east of Aviemore. Research shows young capercaillie can travel 16km from their birth place once fully fledged: the whole of the Lost Forest Phase I area therefore lies within their dispersal zone.

Humans have large brains that can compute from the visible sections of wire to fill in the gaps. Birds have much smaller brains. This helps explain why even fencing on open ground is so dangerous to them.

While orange plastic netting helped make fences far more visible to birds it quickly became apparent it posed a number of problems: it forms a barrier to the wind, making fences in exposed positions prone to collapse, is an eyesore and becomes brittle in sunlight. (And all of that was before there was much much awareness of the polluting impacts of plastic).

A further trial was therefore undertaken along the A9 near Aviemore marking fences with wooden batons (see “An assessment of methods used to mark fences to reduce bird collisions in pinewoods”, RW Summers and D Dugan, Scottish Forestry Vol 55, No 1, 2001). This showed closely spaced wooden batons to be as effective as orange netting. While widely adopted since then, batons are generally now more widely spaced to reduce costs and wind resistance. There has been no research into the impact of this change and the most likely consequence is more birds will try to fly between the wider gaps resulting in a higher mortality rate

Brewdog’s operational plan agreed by Scottish Forestry states that the marked areas shown on the map are “in line with Forestry Commission Technical Note 19 ‘Fence marking to reduce grouse collisions’” and are “in areas where risk of bird strike was agreed with key stakeholders to be high”. Both the marked and unmarked sections of fence have the potential to kill lots of capercaillie and other birds, just one less than the other. Just which stakeholders agreed that the risk of birds flying into the section of fence on the right of the photo was high but that on the left was less high has so far not been made public.

The Lost Forest operational plan also states that:

“fence marking will be of high-cost standard which will include: individual pales 1.2 metre of chestnut / sawn softwood @ 500 millimetres apart at both diagonal ends. Marked areas will be kept under review over the life of the contract to ensure suitable marking remains in place and relevant to sensitive areas. Any evidence of bird strike will be notified to the local Capercaillie Advisory Officer.”

While the spacing of the batons on the Lost Forest boundary may be closer together than some, given the proximity of the fence to known populations of capercaillie erecting a fence here was inexcusable.

Slightly lower down the hillside the deer fence runs through an area of native pinewood that is naturally regenerating, thanks to work by the Kinveachy Estate and NatureScot to reduce deer numbers. Just like Glen Feshie this is just the sort of habitat regeneration which could save the capercaillie and is an area that likely to be favoured by them. Constructing a fence here was completely unnecessary because of all the successful regeneration and serves to undermine all the other public money and work hat has been invested in trying to save the capercaillie.

BrewDog’s operational plan states that most of the other deer fencing within the Phase I Lost Forest boundary fence will be removed within two years of its construction:

“Existing fencing within the new enclosure which will be made redundant has been prioritised for removal. Priority for removal of redundant fencing is based on risk of bird strike, public access, and visual sensitivities.”

When I visited in October and December most of those fences seemed to be still in place. We will never know how many birds will have died as a result but if Scottish Forestry had insisted all fencing that was now redundant from its perspective had been removed in three months, that would have made a significant difference. It might even have saved a few capercaillie.

Scottish Forestry agreed that BrewDog could retain one section of internal fence, running up the hill from the gate to the boundary fence. The justification for this was that extensive woodland to the southeast of that fence (the right side looking up the hill in the phone) made reducing deer numbers there difficult and to help reduce the impact on new tree growth it was better to keep these deer in a fenced compartment. This fencing, as shown in the map above, was supposed to be marked. So far that has not happened. How many more birds have died unnecessarily as a result?

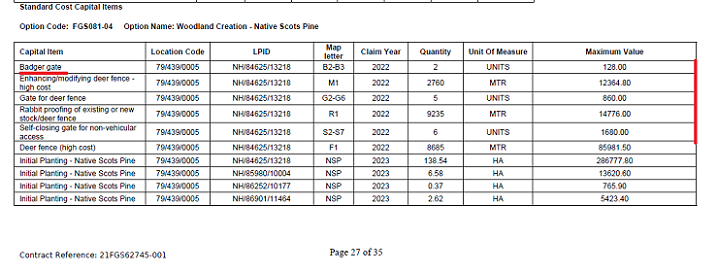

BrewDog’s boundary fence is designed to keep all animals, not just deer, out. While slower moving animals are unlikely to collide with deer fencing, it still has a considerable impact because of the way it segments habitat. While this is not that well researched in Scotland, it has been recognised for some species: hence why, after paying BrewDog c£100k to put up deer fencing and further money for “rabbit proofing”, Scottish Forestry also agreed to pay them £128 for a badger gate in 2022 (see below). The public are being asked to pay to create a problem and then pay to solve it!

The segmentation of habitats is likely to have a particularly severe impact on mammals in winter when it is known that animals like mountain hare (like deer) try to move downhill in bad weather. But limiting the movements of animals, whether herbivores or carnivores, by keeping them inside the fence or out, is likely to affect their survival rates at all times of year.

The wire netting also impacts ground nesting birds which, after their chicks have hatched, will often lead them on foot to lower ground (and more food). Unfortunately none of this is well researched although there is growing awareness of the need to do so outside the UK (see here).

BrewDog’s Operational Plan states that:

“All fencing and access structures are designed to comply with the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.”

and

“Along the ‘Burma Road’, deer grids (with winter closure gates during periods of snow) and pedestrian gates suitable for walkers, cyclists and horse riders, will be provided. Pedestrian gates will also be installed at all locations where mapped footpaths cross the proposed fence line and stiles installed in locations with strong desire lines which see regular usage.”

That sounds fine until you realise there are almost no paths! And the rabbit netting means its even more difficult to cross the deer fencing than is usually the case:

The capital items map above shows crossing points in the boundary fence. These are completely inadequate and should never have been approved by Scottish Forestry which, like other public authorities, has a duty to uphold the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.

Publicly funded ecocide?

BrewDog’s defence of the deer fencing in its operational plan is that it is a temporary measure and will be removed in due course:

“Following consultation with key stakeholders it was decided the proposed fences would be removed once the new woodland was successfully established in order to limit any potential negative impacts to a fairly short period relative to the woodland, which is estimated to be around 10 years but may be extended in line with the resilience/vulnerability of the new woodland. Fence removal before year 20 will be agreed in advance with Scottish Forestry to ensure successful establishment and resilience has been achieved. The fence may be retained to as long as 30 years depending on rate of establishment. This will be monitored regularly once the stand has reached year 10 to inform a decision for removal. Rabbit netting will be made porous and/or removed once trees have reached a height and girth to resist damage from hares, this is expected to occur as early as 5 years but will be informed by monitoring of tree growth.”

On this argument and given how the planting has gone so far, with many of the trees having died, the fencing is likely to still be in place in 20-30 years time. It will have become ineffective at blocking animals long before then (most deer fencing remains effective for 10 years at most). It will, however, still be killing capercaillie if any still survive by then.

Moreover, the fact that BrewDog got Scottish Forestry’s agreement to keep an internal section of fence to contain the existing deer population raises serious concerns about BrewDog’s commitment to control deer numbers.

Scottish Forestry has handed BrewDog considerable sums of public money to pay for this deer fencing disaster. Here are the figures for 2022:

That is c£100k for fencing without taking account of the payment for gates. While I have not been to see it yet work also appears to have started to erect deer fencing for Phase 2 of BrewDog’s Lost Forest project around the Caledonian Pine forest on the Dulnain:

If there was a substantial reduction in the deer population (to a maximum of 2 per sq km) we would not need these fences that are killing Scotland’s birds, affecting the survival rates of both birds and animals and presenting a barrier to the right to roam. BrewDog could have followed the example of Wildland Ltd but appears to have chosen not to do so.

The evidence suggests that the impact of deer fencing on wildlife amounts to wanton destruction of the natural world. As such it fits the definition of ecocide as set out in Monica Lennon’s Ecocide Prevention Bill (see here). Conservationists should be pressing for that to become law as soon as the threat of criminal prosecution would be one way to force land-managers and organisations like Scottish Forestry to change their ways.

Until then it is still shocking that the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) has said nothing publicly to try and stop BrewDog and Scottish Forestry from erecting this new deer fence in an area so important for capercaillie. Both their Board and staff need to get out more and see what is happening on the ground. The CNPA should also be calling on the Scottish Government for an immediate ban on such fencing in the National Park and focussing its attention on reducing deer numbers.

Kinrara would have been an ideal place to start given the woodland here was already regenerating naturally, as I showed before Scottish Forestry approved the Lost Forest project (see here) and there was therefore absolutely no justification for either the planting or the deer fence. Since then an ecological disaster has unfolded with large amounts of carbon having been released into the atmosphere and a large proportion of the planted trees having died (see here) on top of all the dead wildlife.

There are several qualities of Deer post available. When viewed from a distance ‘like is not necessarily like’.

Round slow-grown debarked poles of small diameter; Square sawn posts, in which the milling will inevitably have exposed end-grain, posts of either type once part- treated with a preservative to a certain height, or entirely pressure treated during full immersion for 24 hours.

In view of this clear variety of materials, it is highly questionable whether any deer fence except those built with the most well treated preservatives eg; Boron,Cupro Tanalised or Creosote based products ? could be considered to have an exected lifespan for as long as 20 years after erection across wet moorland.

Dare we ask what this level of preservative does to the fragile mountain soils into which it is bashed?

Who exactly does this reported Brewdog assurance, concerning the anticipated life of new investment into (unecessary?) fencelines across open spaces, actually serve to appease.?

This link helps to set out statutory industry standards and wood product treatment levels from 2021 onwards. https://www.thewpa.org.uk/preservative-treatments

The slopes planted and fenced by BrewDog are no longer one of the best areas near Aviemore for skiing. Before BrewDog arrived these wide open spaces provided for multiple descent routes under good snow cover – just one more reason for getting rid of all this ridiculous deer fencing and then repairing the disturbed ground by replacing the mounds that now carry thousands of dead planted trees. We now need a local community development trust to use the compulsory purchase powers available under part 5 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 to remove BrewDog from our national park. It is time for these greenwashing corporate clowns to lose their so called “Lost Forest” and focus their energy on what they do best, brewing beer not planting trees. Then the rest of us can ensure that the future expansion of Kinrara’s woodland is achieved entirely by the natural regeneration of its existing Scots pine, birch and other native species. Pass the Punk IPA for us all to drink to that.

What a good idea. Dave.

Larch fence posts are naturally durable and do not require treatment.

Is disruptive activism required to make sense of this madness ?, and I include all subject matters on ParksWatch.

What a farce. The Scottish Government, with massive financial deficits, gives huge amounts of money, via Scottish Forestry, to a multi billion pound company so that they can claim carbon credits to pretend that their brewing operation is carbon neutral. You couldn’t make it up!

With natural generation going on a pace in the neighbouring estates, has Scottish Forestry and the Scottish Government lost all sanity? I assume we will see Lorna Slater paying a visit to congratulate Brewdog for trashing the environment at some time in the near future.

Sorry, posted again for formatting.

Nick, you and your fellow contributors once again choose to ignore, as you have repeatedly done, the elements of Natural Regeneration included within Brewdog’s plan for the Lost Forest.

Why not tell your readers that 24% of the land covered by Lost Forest phase1 of the afforestation scheme is given over to natural generation?

You know this Nick, you’ve previously posted a link that details this, but continually ignore this fact and again fail to reference it here.

Your readers won’t know this as you repeatedly make it sound as if the Lost Forest is all about planting, when it also includes natural generation.

Similarly in your repeated mentions of Wildland and natural generation, why not tell your readers that Wildland have in fact planted Five Million trees in the Cairngorms?

Put another way, Wildland have planted Ten Times the number of trees planted by Brewdog in Lost Forest phase1.

Your readers won’t know this from the way you continually reference Wildland and natural generation.

Lost Forest and Wildland are both combined Planting and Natural Generation afforestation schemes.

To correct some statements in the comments of your fellow contributors.

While Gordon Bollock states “You couldn’t make it up”, he appears to be doing so.

Brewdog is not a “a multi billion pound company”, it is loss making, perhaps he can provide some support for his valuation?

Brewdog doesn’t “pretend that its brewing operation is carbon neutral”, it States it is Carbon Negative. It publicly publishes its emissions, these are independently and externally audited. It then shows the calculation to support its Carbon Negative statement.

He further states “With natural generation going on a pace in the neighbouring estates”, and ignores, like you, the Natural Generation elements of the Lost Forest, 24% of the land in Phase 1.

Again like you he ignores the Five Million trees Planted by Wildland on neighbouring estates in the Cairngorms.

Dave Morris proposes a local community development trust should use the compulsory purchase powers to “remove Brewdog from our national Park” but fails to mention the basis for any argument as to how this could have any chance of being successful.

He refers to “greenwashing corporate clowns”, this demonstrates a total lack of knowledge or awareness of what brewdog is about when it comes to minimising its environmental impact.

It appears that either both Gordon and Dave have failed to read the Link you previously posted to Brewdog’s Sustainability Report, or they choose to ignore it.

Nick, you and your fellow Contributors are failing in your core objective – to provide Constructive Criticism…..

Collectively you’re failing to deliver critique constructively while selectively ignoring facts that don’t fit or that contradict your stated views.

It is right to challenge what Brewdog are doing with Lost Forest, particularly within the Park, but that’s needs to be done Constructively, Openly and Transparently.

Lastly, £128 gets two gates for the Badgers, not one, as you state. – Go Badgers!

Nathan, I would be extremely happy to write more about natural regeneration on Kinrara, I have on several occasions made the point that there is natural regeneration all over the site and published photos to show this. Why BrewDog should be praised for NOT planting in some of the areas where woodland is regenerating naturally I am not sure. The real issue is that almost of the Speyside part of Kinrara would have regenerated naturally and BrewDog has planted many areas where there was already extensive natural regeneration as I showed in my previous post. The ironic thing is many of those planted trees have died while the naturally generated trees around have survived.

In relation to your points about Wildland Ltd you are not comparing like with like. Wildland Ltd has NOT planted Glen Feshie where, like Kinrara, there was an extensive seed source. The planting has all taken place between Glen Tromie in an area where there was almost no woodland. The justification for this at the time it happened was people were claiming trees would never regenerate naturally due to the lack of seed sources. I also went to take a look at that at New Year and will blog about what I saw in due course. Suffice to say now I found evidence that is only partly right and I think planting that many trees was a mistake. However, there was and is more justification for planting there than on the River Dulnain, which retains Caledonian Pine Forest fragements and where there is a much greater food source. I will be blogging again on BrewDog, including its financial position and how much it is investing at Kinrara soon.

Nat – “Brewdog is not a “a multi billion pound company”, it is loss making, perhaps he can provide some support for his valuation?”

Might want to tell Brewdog, their founders and their investment bankers that:

“How much is Brewdog worth?

Brewdog could be valued at around $2 billion in its upcoming IPO, based on its most recent valuation. The firm sold shares to 220,000 customers through a crowdfunding round at £25 per share, which raised £7.5 million and gave the firm a market cap of £1.8 billion.

Watt’s 24% stake was estimated to be worth around $480 million, and co-founder Martin Dickie’s 20% share around $400 million.”

https://www.cityindex.com/en-uk/news-and-analysis/everything-you-need-to-know-about-brewdog/

From the mutts themselves:

“Since the producers turned us down, we have gone on to build a pretty neat little business which is currently valued at £1.8 billion and which has raised over £250m.”

https://www.brewdog.com/blog/when-dragons-den-turned-down-brewdog

Of course, the alternative is they’ve been fleecing their fanboys for shares actually worth much less all these years – you decide.

Hey Inverasdale, your reply reads very much like a poorly researched blog that was recently posted elsewhere then removed by the author after being widely criticised, ridiculed even, for its source and inaccuracy.

Last best guess for Brewdog’s valuation was the last trading day price of £6.50, and shares continue to trade around that price.

With upwards of 75 million shares issued that’s something like a £500m valuation, a long way short of “a multi billion pound company”.

The poster I referred to above – wasn’t you was it ? – also cited the same city index article.

This article has been discredited on a number of online forums.

Not least because it’s a “scrape” copy and pasting from a number of online sources unchecked, the information quoted in it is outdated/inaccurate.

It’s also been pointed out how lazy a copy and paste job it is as it contains references to Birkenstock – obviously a different company entirely.

I can’t get your other link to work.

Brewdog could be valued anywhere between £500m – £1.8B, at future IPO, what it’s worth now though, based on the most recent share sales is at the £500m end.