It is just over a year since I explained how the Cairngorms National Park Authority has ignored the role of deer fencing in the decline of capercaillie (see here). While the causes of capercaillie and black grouse decline are complex – they include loss of habitat and climate change – the one thing that has been proven beyond doubt and for over thirty years is that deer fences kill:

The message was clear, only fence where “absolutely essential”. Since 1995 the range and population of capercaillie has decreased considerably and the core surviving population is found on Speyside, hence how the Cairngorms National Park Authority got funding for the Capercaillie Project.

While the Capercallie Project did some good work identifying deer fences on Speyside (see here), instead of removing fences which had “served their purpose” they decided to fund land managers to mark fences. While this had been shown to reduce mortality rates from collisions by 60%, the research indicates that large numbers of grouse of all species are still dying unnecessarily each year:

The public rarely witnesses the carnage because opportunistic predators like foxes quickly learn there are easy pickings to be had from patrolling deer fences. That is why sound research requires daily checks.

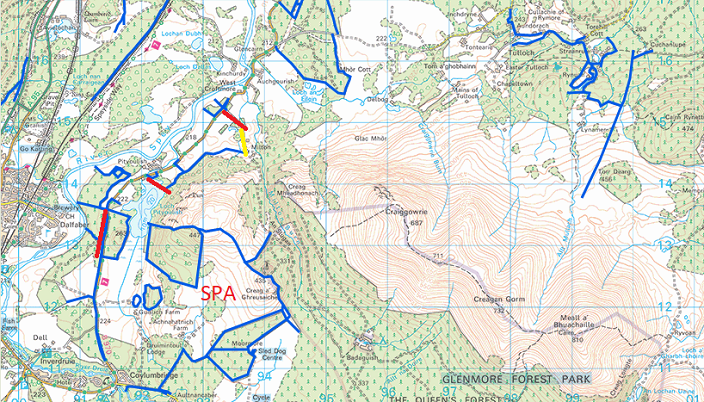

Driving along the B970 between Nethy Bridge and Coylum Bridge last week, I spotted new fencing without markings just north the Glenmore Forest, one of the main areas for capercaillie. I walked along the track to Milton to investigate.

About 700m down the track, after a stretch of old deer fencing, another section of new deer fencing appeared, this time marked:

So why did the Pityoulish Estate, which appears to own this land, mark one fence but not the other when a recent study (2020) has found that young female capercaillie on Speyside (see here) dispersed by up to 16km? Or more to the point, what has the Cairngorms National Park Authority done to stop new deer fencing being erected in core capercaillie areas?

So why did the Pityoulish Estate, which appears to own this land, mark one fence but not the other when a recent study (2020) has found that young female capercaillie on Speyside (see here) dispersed by up to 16km? Or more to the point, what has the Cairngorms National Park Authority done to stop new deer fencing being erected in core capercaillie areas?

I spotted another section of new fencing on the estate close to Loch Pityoulish (sorry no photo). This was even closer to the Cairngorms Special Protection Area, part of the purpose of which is supposed to be to protect the capercaillie.

A little further south the B970 passes through land owned by Rothiemurchus. This is bordered by a delapidated deer fence which had clearly ceased to serve any useful purpose in terms of keeping deer out of woods.

While only too happy to accept grants for deer fences, most landowners are not so keen to take them down (Wildland Ltd and RSPB at Abernethy are notable exceptions). As a result the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) has approached Scottish Forestry suggesting they should provide new funding to remove old deer fences. Meantime, as soon as capercaillie and black grouse move out of fenceless areas, significant numbers face probable death.

In my post 13 months ago I referred to the deer fencing on the dualled section of the A9 south of Aviemore which was completed five years ago. The area is well within the 16km dispersal zone for young capercaillie and Transport Scotland, as part of the A9 dualling project, had committed to marking all the fencing. It hasn’t. Driving south I made a point of checking and the fencing changes from unmarked, to marked, to unmarked, to marked and back to unmarked.

If any dispersing capercaillie or black grouse were flying towards the batons at this point the chances are they would swerve into the section of unmarked fence! Perhaps the top brass at Transport Scotland should check whether they will be held criminally responsible if the Ecocide Bill becomes law?

Meantime, the question is why has the CNPA, which is supposed to co-ordinate the approach to conservation by our public authorities through its National Park Partnership Plan, allowed Transport Scotland to get away with this?

I continued on for a ski up Glen Banchor, where there was a reasonable amount of snow on the floor of the glen but none on the hill. Up at the new woodland restoration enclosures planted by the Woodland Trust – about ten miles from Glen Feshie where there are capercaillie – the deer fences are marked with batons.

The fences around the older plantations, however, have no markings resulting with the same problem as alongside A9: any grouse that see the new fences because of the batons may well then collide with the old ones. This is piecemeal and pathetic conservation. Having paid towards the cost of the Woodland Trust planting the trees one might have thought NatureScot would at least require the Glen Banchor estate to mark any intact enclosures and remove those that are redundant.

We headed up to one of the plantations where the Glen Banchor estate wanted to extract the timber by constructing a new road over the moor to (see here). We counted over 100 deer just above, reluctant to move because of the snow. They would have been easy to cull in these conditions but the fencing of the new conservation woodland below is a direct consequence of the failure by our public authorities to require the Glen Banchor estate to do so.

The deer had clearly been using the wood for shelter in the bad weather and over time eaten everything worth eating. One wonders how long the Woodland Trust enclosures will last? Ten years, perhaps, after which we will likely end up with yet another failed native tree plantation paid for out of public money. Meantime, even if no capercaillie ever reach Glen Banchor how many black grouse will have collided with them?

I have seen quantities of black grouse feeding on the perimeter of similar plantations in Glen Feshie, where the fencing has been removed and the woodland understorey recovered because deer numbers have been reduced. They have no such chance in Glen Banchor.

Discussion

Although I have commented on the failure of the CNPA to tackle deer fencing previously what struck me on my journey from near Pityoulish to the head of Glen Banchor was its extent and how much is unmarked.

While some of the estates in Cairngorms Connect have been doing excellent work on removing deer fencing completely, elsewhere the land is criss-crossed with deer fences: some old, some new; some marked, some not. Low flying birds, particularly the larger ones which inhabit woodland like the black grouse and capercaillie, have little chance chance. Despite 20 years of effort to save the capercaillie and despite the work done to by the Capercaillie Project to identify deer fences, their last remaining stronghold on Speyside is a death trap.

It should be no wonder the capercaillie have collapsed but if it is to survive, its population needs to expand. The most pressing challenge is that as soon as the young try to disperse after a good breeding season they face multiple mortal hurdles in the form of deer fences. With perhaps 60% of the dispersing bird dying through collisions, the species has little chance. It would take at least six birds attempting to disperse to the same new woodland and two of the opposite sex to survive for any breeding to take place.

An indication of the conservation failure is that in some respects the situation with regards to deer fencing has got worse, not better. It was Forest Research, who produced that excellent note on the impact of deer fencing in 1995, who have put up an experimental forest enclosure in the middle of Glenmore Forest, the heart of capercaillie territory, on land owned by Forest and Land Scotland (FLS) (see here). If Forest Research won’t observe their own advice, its not surprising few others do.

Meantime, instead of focussing on taking down the deer fences, the CNPA, NatureScot and Forest and FLS have been sponsoring and encouraging research on the impact of predators and outdoor recreation on capercaillie. Neither is likely to have played a significant role in their decline, with predators having evolved alongside capercaillie (see here) and capercaillie having lived alongside people for many years – until they were hunted as game birds and culled. Indeed, the post-war decline of the capercaillie was partly precipitated by the forestry industry with the Forestry Commission shooting capercaillie to prevent them eating the leading shoots of young pine trees. Now FLS fences those same plantations to prevent deer doing the same in the course of which it has been responsible for the deaths of yet more capercaillie.

The issue of course is the number of deer. Reduce the deer to 2 per kilometre or less as Wildland Ltd have done in Glen Feshie and the National Trust for Scotland have done at Mar Lodge and you can get rid of the killer deer fencing. Unfortunately the CNPA has committed in its National Park Partnership Plan to reduce deer to 6-8 per square kilometre, far too high a density for trees to grow without protection. Subsequently and even more unfortunately the Scottish Government has now endorsed that figure for the Cairngorms in their Biodiversity Strategy. In doing so they appear to have have effectively signed a death sentence for the capercaillie.

In an interesting article this week in the National (see here) Steve Micklewright, Chief Executive of Trees for Life and a recent appointee to the CNPA board, rightly called for urgent action to save Scotland’s Caledonian pine woods on the tenth anniversary of the Scots Pine being declared Scotland’s tree. After explaining how Caledonian pine woods are important for certain species, including the capercaillie, and arguing deer numbers need to be reduced, Mr Micklewright claimed:

“Fencing to exclude deer is only a temporary fix, but for now – until effective landscape-scale deer management can be properly established – it’s a key way of giving the old Granny pines the chance to set seed successfully and ensure a healthy population of new trees.”

This is just not true. Trees for Life may rely on fencing for their conservation work in the West because FLS and private landowners neighbouring Glen Affric have failed to reduce deer numbers as has happened on Mar Lodge and Glen Feshie. But what the National Trust for Scotland and Wildland Ltd have shown is that reduce deer sufficiently – and where there are isolated granny pine this may need to be to less than 2 per square km for a time – and Scots pine will regenerate without any fencing.

This was in fact acknowledged by Mr Micklewright in the article:

“Dramatically reducing deer numbers, meanwhile, can enable a whole new forest to naturally regenerate quickly, as superbly demonstrated in Glen Feshie in the Cairngorms”.

So why not just reduce deer numbers rather than pay for expensive killer fences?

The problem is that so long as the average deer numbers in the Cairngorms are 6-8 per square kilometre, as per the CNPA’s target, natural regeneration or planting of trees relies on deer fencing. For the last twenty years certain conservation charities like Trees for Life and the Woodland Trust have been justifying this as “a temporary fix” until deer numbers reduce. This diverts money which could have been used to cull deer instead of killing capercaillie. Until that changes, we stop funding deer fencing and force forest managers and sporting landowners to deal with the deer problem, the “temporary fix” will go on and on.

While it can be very difficult for conservation organisations operating in areas dominated by large sporting estates to press for a reduction in deer numbers, our National Parks should be different. I would hope that Mr Micklewright has a re-think and uses his position on the CNPA Board to argue that they should be taking a lead and for deer numbers on Speyside at the very least to be reduced to 2 per square kilometre. That would enable all the deer fencing on Speyside to be removed and would give the capercaillie a chance.

There is now an opportunity to do this and for the Scottish Government and CNPA to change course. The latest Scottish Government budget included a 40% cut in Forestry Grants due to continued pressure on the public purse. With a much more limited forestry budget, it would be a good time for the Scottish Government to adopt a policy presumption against deer fencing and replace it with a commitment to reduce deer numbers across Scotland.

The problem is not confined to deer fences. Grouse moor owners wanting to contain the sheep they have taken over as tick mops have erected many km of ordinary fencing over the hills and the top wire is at the height grouse often fly at with inevitable consequences. I believe Candacraig estate took out the top wire to reduce collisions.

Deer and other abandoned fences like field are simply another form of litter and can be a down right dangerous one. I recall numerous times when I or companions tripped over or found our feet entangled in old half buried fencing wire. The practice of toping field fences with a strand of barbed wire. is making it worse.