Last week I went out at Balmaha, the first time for over a year, and was greeted by a new forest of tree tubes. It looks terrible, is terrible for nature and ,this post argues, it exemplifies what is wrong with the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) and its new National Park Partnership Plan.

The Balmaha Plantation is owned by Scottish Government Ministers and managed by Forest and Land Scotland (FLS). They have for over 20 years been working to restore and re-wild the former coppiced oak woods on the east shore of Loch Lomond. The Forestry Commission had previously felled and underplanted many of those oak woods to grow conifers which were regarded at the time as more useful commercially.

The Sitka and larch visible in this photo have been felled, the larch possibly as part of FLS’ attempt to halt the spread of the tree-killer phytopthera ramorum, while retaining as many native trees as possible. So far, so good, a reversal of past mistakes.

However, the felled area has then been re-planted mostly, as you can see, in unnatural straight lines – a replicationcontinuation of the plantation approach to forestry – while the trees, most likely oak, have been “protected” by plastic tree shelters.

Work by the Forest Plastics Working Group (see here) suggests that whether the plastic in the tree tubes is derived from oil, as is most likely, or natural polymers makes very little difference:

“Bioplastics are problematic because they must be recovered from site and it is thought that they behave in a similar way to microplastics and their chemical impacts are not fully understood”

The revised UK Forestry Standard, approved for use in Scotland by Scottish Ministers in the Autumn, now recommends all tree tubes should be removed after use. Even if FLS plans to do that here in due course – one wonders whether they have calculated the cost?- the plastic will have already started to break up and enter the natural ecoystem, polluting both the “restored” oak wood and the waters of Loch Lomond below.

If the plastic shelters are derived from oil, as is commonly the case, they are helping Scotland to emit more carbon, not less. This makes a mockery of the extravagant claim made in the LLTNPA’s new National Park Partnership Plan :

“the superpower of this National Park’s landscape is that it can transform, going beyond Net Zero and becoming carbon negative, absorbing more carbon than it emits, helping Scotland and the wider world reach its ambitious climate targets”.

The need for tree shelters?

Most of the east Loch Lomond oak woods were a deliberate human creation, around pockets of much more ancient woodland, and the area around Balmaha has been planted and replanted over time all, until now, without the “help” of plastic tree shelters. This worked because grazing was strictly controlled and would have worked now if the same principles were applied.

Moreover, with low grazing levels, native woodland would also regenerate naturally without any need for planting. The reason most of the east Loch Lomond oak woods were planted was because oak was needed in a hurry for industry. But then, once established, they also in places regenerated naturally where grazing continued to be controlled. Where we want native woodlands for nature, rather than industrial and commercial use, control of grazing and natural regeneration should be the only way to go.

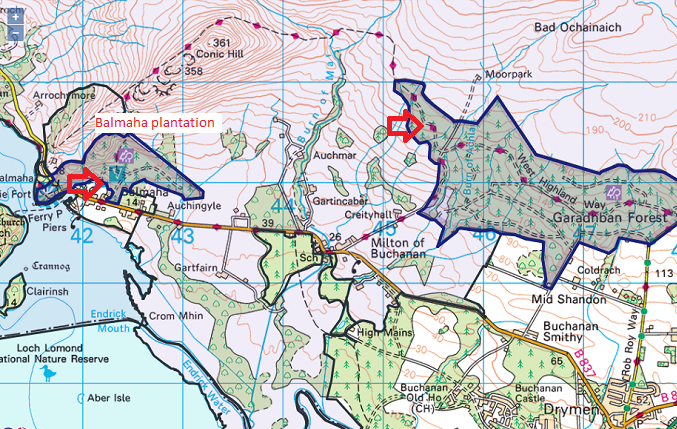

I came across good evidence for part of this argument a couple of hours later. Having found that the main Conic Hill path was “closed” for repairs, I tried approaching it from Garadhban Forest to the east (see map above). The area of planted native woodland there had grown considerably since my last visit, all without the use of tree tubes. The oak appeared to be doing fine even if it was part of an even-aged forest which lacks structural diversity. So why has FLS now taken to encasing the native trees it plants in plastic?

Why nature conservation is failing in the National Park

Shooting deer in large conifer plantations is notoriously challenging but in small areas of native woodland, like the Balmaha plantation, deer control should not be difficult and, where dense conifers are replaced by open native woodland, should be easy. The money FLS has spent on buying the trees and plastic shelters, planting the trees and then removing the plastic would have been far better spent on a local forester, who could keep an eye out for deer and weed out the sitka saplings as they regenerate all around the planted oak from seed in the ground.

Situated next to the underused National Park Visitor Centre and at the gateway to east Loch Lomond, the Balmaha Plantation should have been the ideal place to demonstrate and inform the public how natural processes work, including the role birds and animals play in the natural regeneration of woodland. Instead, its a glaring example of how NOT to restore native woodland. What a missed opportunity!

One of the headings in the LLTNPA’s NPPP is “UNCOMFORTABLE TRUTHS THAT THIS PLAN AIMS TO TACKLE”, Missing entirely from the list of uncomfortable truths is the fact that most human attempts to restore or improve nature have had disastrous consequences and we cannot continue to do things like use plastic tree tubes. We would be far better off leaving the restoration of nature to nature with minimal intervention.

Bycontrast to the Cairngorms National Park Authority’s NPPP, the LLTNPA’s NPPP contains no policy statements setting out how things should be done in the National Park. There are many holes in the CNPA’s policies but at least they have them and can use these to influence their partners – for example their policy presumption in favour of natural regeneration and against forest fences. The LLTNPA could have taken a lead and done the same for plastic. Without such policies the LLTNPA is not going to change anything about the way FLS or other public authorities operate in the National Park.

From a conservation perspective the LLTNPA is almost completely redundant and its only real function is to disburse government grants for peatland restoration. One of the revealing statements in the board paper that accompanied the NPPP was the following:

Two responses were received requesting the identification of rewilding areas in the National Park, and identifying targets for this, however this terminology has not been incorporated.”

This is not an accident. The LLTNPA are not just avoiding re-wilding terminology, they are avoiding the whole philosophy. That is why the plastic planting at Balmaha has been allowed to happen without a murmur of protest. Enabling natural processes to thrive with minimal human intervention, whether on public or private land, would undermine the LLTNPA’s claims that private investment is needed to restore nature.

While there is nothing in the NPPP that will do anything to prevent practices which are harmful to nature, like the use of plastic tree shelters, there is enough to legitimise the LLTNPA assuming a new function, that as an enabler of private finance. Our National Park Authorities are being turned from what they should be, agents of conservation and sustainable development, to become agents for private interests.

Between your two arrows is the Burn of Mar hydro scheme. You probably remember that the tree planting and restoration required by the planning consent was never carried out. LLTNPA ignored my formal complaint and did not pursue the developer. No natural re generation of the original riparian woodland seems to have occurred. The site still looks a mess nearly 10 years later and adds to the general environmental degradation in that area. This could easily have been prevented by a properly functioning LLTNPA.